🌊 The Great Atlantic Ferry: The Rise of the Cunard Line and the Transformation of Ocean Travel (1840–1902)

📌 Explore the extraordinary 1902 profile of the Cunard Line from Business Illustrated, documenting the company's rise from wooden paddle steamers to the most luxurious Atlantic liners. Essential reading for students, teachers, genealogists, and maritime historians.

Front Cover, The Story of the Cunard Line, Reprinted From "BUSINESS ILLUSTRATED". December, 1902. | GGA Image ID # 100243bf8e

🚢 Elaborate Review and Summary: “The Story of the Cunard Line” (1902)

Originally published in Business Illustrated, December 1902

✨ Introduction: The Cunard Line’s Proud Independence

This 1902 profile, “The Story of the Cunard Line,” offers an extraordinary glimpse into the rise and triumph of one of the world’s most iconic steamship companies—Cunard. Published during a turbulent time when American capital was sweeping up competing British lines into large trusts, this article celebrates Cunard's steadfast independence and loyalty to the British crown and its shipping legacy.

It is a treasure trove for 📚 teachers, 🧑🎓 students, 👨👩👧👦 genealogists, and 📜 historians. It charts the transformation of transatlantic travel from primitive paddle steamers to palatial steel leviathans equipped with electric lighting, Marconi wireless systems, and sumptuous salons worthy of royalty.

Cunard Steamship Company, Limited, one of the oldest and most famous of British steam navigation undertakings elected to remain independent and outside the scope of the great Trust. This is their Story as published by BUSINESS ILLUSTRATED. December 1902. Lavishly Illustrated including Interior Photographs.

The Story of the Cunard Line

The stirring story of the ocean steamship enterprise in 1902 will remain one of the remarkable memories. During this year, Great Britain's supremacy in the Atlantic shipping trade was seriously threatened for the first time.

Even as it is, the blandishments of American capital, handled on Napoleonic lines, and the fascinating possibilities of enterprise on a colossal scale have together succeeded in absorbing within one huge combination several British Atlantic steamship lines, which had previously been engaged in active coin-petition.

As expected, this proceeding generated sensational interest unprecedented in the history of the shipping industry.

Happily, the Cunard Steamship Company, Limited-- one of the oldest and most famous of British steam navigation undertakings--was one of those concerns that elected to remain independent and outside the scope of the great Trust and, with the support and co-operation of the British Government, it has, within the past few months, entered upon a new chapter in its history, under conditions which are likely to maintain the splendid traditions of the Cunard Line.

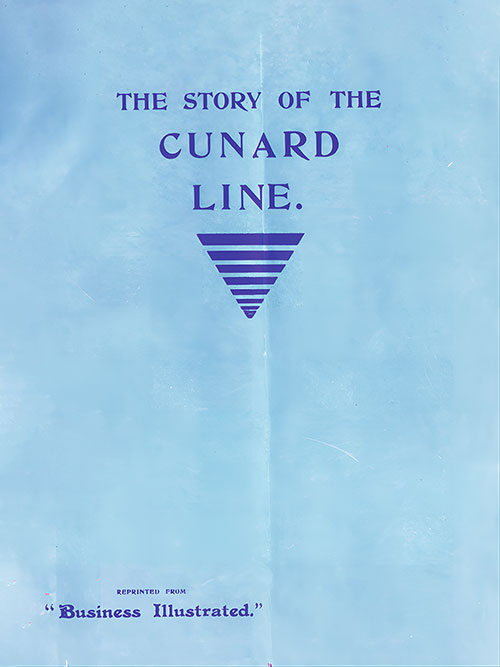

Clockwise from the top: Sir Samuel Cunard , David MacIver , and Sir George Burns. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 100264e46e

The Founders of the Cunard Line

Given what follows in this article, the terms of the arrangement concluded with His Majesty's Government may be recapitulated here.

The Cunard Company is to add two large, high-speed steamers to its fleet for the Atlantic trade. In terms of management, shares, and vessels, it has pledged to remain a purely British undertaking for twenty years from the completion of the second of these vessels.

During the currency of this arrangement, the Company holds the whole of its fleet, including the two new vessels and all others as built, at the disposal of the Government, which is at liberty to charter or purchase all or any of these vessels. The Cunard Company also undertakes not to raise unduly freights or give foreigners preferential rates.

The Government will supersede the Admiralty subvention by paying the Cunard Company £150,000 per annum and lending the Company the necessary funds to construct the two new vessels, charging interest at 2¾ percent per annum. The security for the loan is a first charge on the two vessels, the Company's present fleet, and its general assets.

The arrangement is creditable to His Majesty's Government and the Cunard Company. It is one, moreover, which is fraught with great possibilities.

It may, for one thing, be the precursor of means that will repair those disabilities from which British ship owners have long suffered in comparison with the ship owners of rival nations, whose efforts are supported by the bounty system.

It is the existence of this system in connection with the ocean steamships of other countries which, amongst other effects, has temporarily deprived British ship owners of the honor of being the holders of the record for speed in crossing the Atlantic, which it was their proud boast to possess for many a year.

Undoubtedly, the new vessels to be added to the Cunard fleet will once more secure this honor for British liners. In any case, the circumstances in which the Cunard Company now finds itself placed are eminently calculated to foster that spirit of enterprise for which the Cunard Line has always been celebrated.

The close of 1902—marking as it does a period fraught with much momentous change to British shipping and allied interests—seems to form an appropriate juncture to review the history of the Great Atlantic Ferry.

In a fuller measure, tell the story of the Cunard Line, which has filled so prominent a place in the annals of British shipping. The occasion, too, is opportune because it closely synchronizes with a memorable period in later British history—the Coronation of King Edward VII.

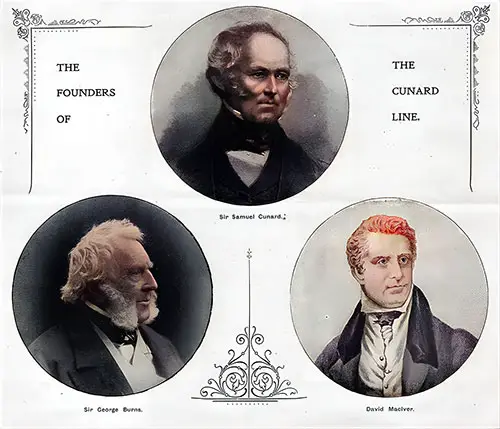

The First Cunarder: The Britannia. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 100209d6d6

The first voyage of the Britannia (Shown Below), the pioneer vessel of the Cunard fleet, in 1840, deserves in many respects to rank not only as one of the significant events of the Nineteenth Century but also as one of the epoch-marking incidents in the history of civilization. It signalized the dawn of organized ocean travel, which has resulted from such mighty developments since then.

Rather more than a score of years previously, the Savannah, an unpretentious steamship of some 350 tons burthen, made an adventurous passage from Savannah to Liverpool, but she did not rely solely upon her paddle wheels; indeed, she trusted entirely to her sails when the weather was " dirty."

It was not, however, until the 4th of April, 1838, that any further steam venture of the kind was made. On that date, the Sirius left London for New York with ninety-four passengers aboard. She was followed from Bristol four days later by the more historic Great Western -- the first steam vessel specifically built for the Atlantic passage.

The Great Western made her journey in fifteen days- two days less than the Sirius- with still 200 tons of coal left in her bunkers. This result was regarded as passing wonderful, for had not one of the greatest scientific men of the time " proved " to the satisfaction of most of the world that no steamer could carry coal enough to feed her fires for a single trip across the Atlantic?

Among the few skeptics as to the truth of this pronouncement was Mr. Samuel Cunard, who had quietly been nursing a scheme for organizing a regular service of Trans-Atlantic mail steamers for several years.

Mr. Cunard, who was once described during the fifties as "a small, grey-haired man of quiet manners and not overflowing speech," was born in 1787 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where his father, a Philadelphia merchant, had settled.

Mr. Samuel Cunard had been engaged in conducting the mail service between Boston, Newfoundland, and Bermuda. When the British Government intimated their disposition to transfer the carrying of the mails between Liverpool, Halifax, Boston, and Quebec from the old Government " coffin brigs," as they were irreverently called, whose passage averaged six or eight weeks, to a steam packet service, if a suitable tender were submitted, he thought the time had arrived for action.

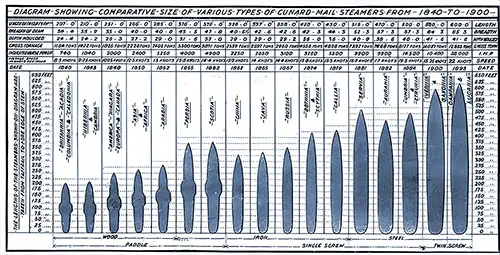

Diagram showing the Growth in Dimensions of the Cunard Liners from 1840-1900. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 100231e621

The merchants and ship owners of Halifax, however, did not look with favor upon his scheme. So he crossed over to England, where he was fortunate enough to become acquainted with Mr. Robert Napier, famous as a Clyde engineer and shipbuilder, and through him with Mr. George Burns of Glasgow and Mr. David Maclver, of Liverpool, both of them well-known ship owners engaged in the coasting trade between England, Scotland, and Ireland.

A few days later, a scheme was developed, and a capital of £270,000 was subscribed. At the same time, shortly afterward, a seven-year contract between the British Government, on the one hand, and Messrs. Samuel Cunard, George Burns, and David Maclver (whose portraits appear on page 4), on the other, was signed. The Cunard Line was established, the title of which was first selected being."

The British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company." Meanwhile, Mr. Cunard opened an office in London, Mr. Burns presided at the Company's headquarters, which were located in Glasgow, and Mr. Maclver remained in Liverpool to prepare for the service's inauguration.

The Company's policy from the beginning was sound, and the fortunes of the Cunard Line have ever since been identified with this: in the building and equipment of their ships and their manning and service, no expense should be spared in securing the best value obtainable and in maintaining the highest possible standard.

The service commenced with four steamers, and the Admiralty was to subsidize the Company to the extent of £81,000 a year. The keels of four wooden paddle steamers--the Britannia, Acadia, Caledonia, and Columbia--were promptly laid down, and their building marked a noteworthy achievement in the naval architecture of that period.

By way of contrast with the vastly greater things of today, it is interesting to glance at the dimensions of the Britannia, of which an illustration appears above. The good ship measured 207 feet long by 34 feet 4 inches broad by 24 feet 4 inches deep.

She was 1,154 tons burthen, and her engines had 740 indicated horsepower. Her speed average was 8 1/2 knots per hour, and she consumed 38 tons of coal per day. The three other vessels were practically identical in their dimensions and equipment to the Britannia.

On " Independence Day," July 4th, 1840, the Britannia left her moorings in the Mersey on her pioneer voyage with 63 passengers on board amidst the jubilations of an immense concourse of people.

The Atlantic crossing was safely accomplished in 14 days and 8 hours, and the vessel's arrival in Boston Harbor signaled an almost frantic outburst of enthusiasm among the inhabitants of " the Hub of the Universe."

Salutes were fired, and a public banquet was held. Mr. Cunard, who accompanied the Britannia on her maiden trip, was made the hero of the moment. It is recorded, indeed, that within twenty-four hours of his landing on American soil, he was made the recipient of as many as 1,800 separate invitations to dinner--probably a record in that form of gastronomic honor which proved an embarras des richesses ('embarrassment of riches') to the modest but enterprising ship owner.

A View of Liverpool Harbor in 1837. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 100099e821

With the inauguration of steam navigation between this country and America, a new era in the shipping trade and resources of the Port of Liverpool also began.

The illustration below, reproduced from an old picture, represents the appearance of Liverpool Docks in 1837, just three years before the Britannia made its historic pioneer voyage. Compared with the aspect of the river and port, it would not be easy to imagine a more striking metamorphosis.

Today, the magnificent docks extend along the Liverpool shore of the Mersey for more than seven miles and on the Birkenhead side for one mile before turning inland for another couple of miles.

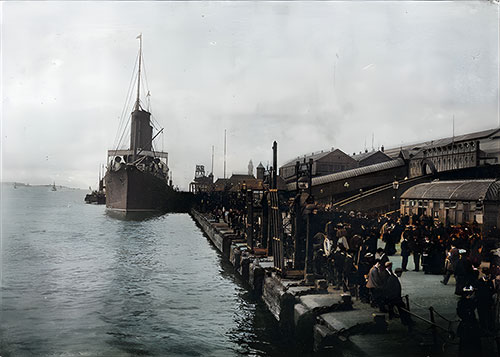

The Liverpool Dock Estate, with its acres upon acres of warehouses, may be regarded as one of the modern wonders of the world. The Landing Stage, part of which is shown in the illustration below, is " the most extensive floating marine parade in the world," measuring as many as 2,463 feet long by 80 feet broad.

The overhead electric railway, seven miles in length along the docks' line, is the only one of its kind in Europe. Last year's statistics show that Liverpool's registered tonnage aggregated 26,616,610 tons, and the city's population, the third largest in the Kingdom, was over 700,000.

The Landing Stage and Riverside Railway Station at Liverpool, with a Cunard Liner Lying Alongside. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 1000de8ca0

It is no empty platitude to say that in realizing the immense development summarized in these few lines, the Cunard Company has been an essential factor. It is interesting to note that the progress of the Cunard Company has been continuous from the very outset of its existence.

The sea-going achievements of the four original vessels were regarded as so satisfactory that, in 1843, the Hibernia and, in 1845, the Cambria were built and launched. Their gross tonnage was increased from 1,154 to 1,422 tons each, and the engine capacity from 740 to 1,040 horsepower, while the passenger accommodation was improved in corresponding measure.

When the first mail contract expired in 1847, the Government was so fully satisfied with the manner in which its conditions had been observed that it was renewed for a further seven years, although on more ambitious lines.

The mail service was to be weekly, and the Government called upon the Company to build four more steamers of still larger size and greater steaming caliber.

The vessels were to be able to carry the heaviest guns then manufactured. While the service from Liverpool was to be weekly, the ports of arrival on the other side were to be New York and Boston alternately.

Under the new arrangement, the government subsidy was increased to 1173,340 annually. As an immediate result, four paddle steamers, every 1,825 tons gross register, 2,000 horsepower, and 251 feet long, were built and named America, Niagara, Canada, and Europa.

The improved service thus rendered possible was inaugurated none too soon, for competition from the United States was not only threatened but, before long, actively instituted by a syndicate of American merchants, who established themselves under the name of the Collins Line.

With a fleet of five large and powerful steamships heavily subsidized by the American Government, the new Line commenced operations with the avowed object of sweeping the Atlantic off the Cunarders."

The struggle was fierce while it lasted, but the Cunard Line fought it with the surest weapons. They would sacrifice nothing calculated to prejudice the safety of their ships or the lives of their passengers.

On the contrary, their efforts were consistently directed towards increasing the safety and comfort of those who supported them by adding new vessels to their fleet, each more powerful, commodious, and completely equipped than its predecessor.

Thus, in 1850, Asia and Africa were floated, followed two years later by Arabia. In 1855, the first iron vessel for the Company's Atlantic service, the Persia, was launched, and in 1862, the almost sister vessel, the Scotia (Shown Below), the last of the old paddle-wheelers, was launched.

Meanwhile, the Collins Line, unable to keep pace with the rapid progress and persistent energy of the Cunard Company, collapsed, having lost two ships. The American Government refused to continue the subsidy.

The Scotia, the Last of the Cunard Paddle-Wheel Liners. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 10014c0c79

While this ended the first serious attempt to compete for the trans-Atlantic traffic, the Cunard Company had to be on the alert lest their prestige should suffer at the hands of others. For now, further Atlantic services were being started between Glasgow, Southampton, Cowes, and American ports.

The Persia and Scotia, however, were the favorite liners with passengers. So far, the Cunard Company had adhered to paddlewheel propulsion in deference to the preferences of most travelers at that time. Still they were, nevertheless, convinced of the superiority of the screw propeller, which marine engineers had long been actively advocating.

They had, indeed, been using screw steamers in their Mediterranean service, and the Inman Line had already introduced the screw system in their Atlantic service.

They decided for the future to adopt the screw. So it was that the Scotia, the handsome vessel illustrated above, was, as has been stated, the last of their paddlewheel liners. The writer well remembers her lying at anchor in picturesque idleness in the Gareloch, off the Clyde, in the late seventies, when withdrawn from her Atlantic career.

A Famous Cunarder - The Russia | (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 46a1918f89

SS Russia and Setting Departure Dates

The first screw Cunarder for the Atlantic service, the China, was ordered in 1862. Regarded somewhat in the light of an experiment, her dimensions were smaller than those of the Persia and Scotia, her length being 326 feet by 40 feet 5 1/2 inches in beam.

Her gross register was 2,539 tons, and her indicated horsepower was 2,250, which enabled her to attain an avenge speed of 13.9 knots.

Having adequately fulfilled the expectations of her owners and builder, China was succeeded in 1865 by Java and two years later by Russia (shown below), which was generally regarded as the most beautiful ocean-going vessel.

Practical men regarded her graceful proportions as the acme of nautical symmetry, and the beauty of her decorations and the completeness of her equipment were the passengers' delight.

Built by the then-firm of Messrs. J. & G. Thomson at their famous Clydebank shipyards, she was 358 feet long (21 feet shorter than the Scotia) by 42 feet 6 inches in beam and 29 feet 2 inches in molded depth.

Her gross register was 2,960 tons, and her engine of 3,100 horsepower gave her a speed of 13 knots in actual service. She consumed 90 tons of coal per day, compared with the 159 tons consumed by the Scotia to attain the same speed.

She accommodated 235 cabin passengers and had a cargo capacity of 1,260 tons. Her commander, Captain Cook, navigated her no less than 630,000 miles without a single mishap or casualty of any kind, carrying no less than 26,076 cabin passengers.

After being sold to another company, she has continued to maintain her splendid sea-going traditions up to the present year.

Apart from the launch of Russia, 1867 was a noteworthy year in the history of the Cunard Line in other ways. When the Company's arrangement with the Admiralty expired that year, the Postmaster-General took charge of the mail packet services.

In the new contract, however, it was stipulated that the Company should despatch a steamer every Saturday from Liverpool to New York, calling at Queenstown for the mail and returning from New York every Wednesday, with a call at Queenstown before proceeding to Liverpool.

By this time, numerous competitors for the mail service had arisen, and the Government was consequently able to reduce their subsidy to £80,000, curtailing it the year following to £70,000. The contract further bound the Company to maintain for seven years a dual weekly service from Liverpool—to Boston every Tuesday and to New York every Saturday.

However, the amount paid for the service was found to be manifestly inadequate, and when the mail contract was again renewed, the work was paid for in accordance with the weight of the mail carried.

This arrangement continues in force today, with the Cunard Company having been the Atlantic Ocean mail carrier for sixty-two years.

The popular mind has little conception of the magnitude of the Atlantic mail requirements. From the outset, they have been uninterruptedly progressive, and there is now an annual carriage of at least 13,000,000 letters, postcards, newspapers, and book packets across the Atlantic.

A large proportion of this quantity of mail is shipped from Liverpool by the Cunarders. Every Saturday afternoon, a special American mail train leaves Euston Station, London, with a later batch, which is put on board the mail steamers when they call off Queenstown on Sunday mornings.

This represents a very smart piece of work. The entire journey from Euston to Queenstown is ordinarily accomplished in about fifteen hours. On the homeward journey, the mail is carried with corresponding celerity, and half an hour after the mail bags reach Euston, they are delivered at the Mount Pleasant depot. An hour later, the postmen are still on their rounds delivering the American mail in the City of London.

Another year of historical importance in the annals of the Cunard Line was 1870 when the Company further advanced from the conventions of ocean steamship practice by adopting the compound principle for its engines instead of the old side lever system.

Although they had just added two fine iron screw vessels, the Abyssinia and Algcria, to their fleet, they purchased the Batavia, which was being built and equipped with compound engines for a company engaged in another trade. They followed this with an order for the Parthia, which was also fitted with compound engines, which, utilizing steam at high pressure, gave better speed results than engines of the old type.

The newer existing vessels were refitted with compound engines, and seven new steamers were similarly fitted, including the Gallia, launched in 1879, which was the last iron Cunarder to be built.

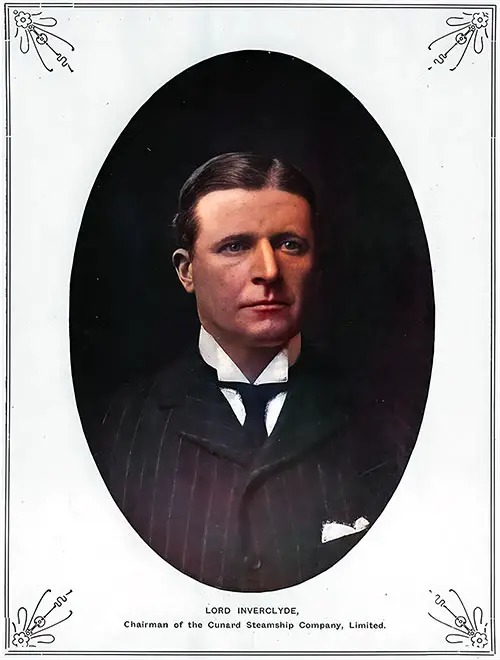

Chairman of the Cunard Steamship Company Limited - Lord Inverclyde. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 10000a53bd

In 1878, the company was registered under the Limited Liability Acts to consolidate the partners' financial interests. It was formed as a joint stock Company with a capital of £2,000,000, of which £1,200,000 was taken up by the Cunard, Burns, and Maclver families.

It was not until 1880 that shares were issued to the public. The prospectus stated that " the growing wants of the Company's Trans-Atlantic trade demanded the acquisition of additional steamships of greater size and power, involving a cost for construction which a large public company might best meet."

The available shares were immediately subscribed, and the directorate reconstituted. Mr. John Burns (afterward Sir John Burns, Bart., and subsequently Lord Inverclyde) was elected Chairman of the Board, which he held until his death in 1901 when Mr. David Jardine succeeded him. The present Chairman, Lord Inverclyde, whose portrait is shown above, is the son of the first Chairman.

The Cunard Steamship Servia (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 10007f167a

With the re-constitution of the Company accomplished, the forward policy of the Cunard Line received a fresh impetus, of which the first essential exemplification was the building of that magnificent vessel, the Servia, illustrated above, in 1881, by Messrs. J. & G. Thomson.

When the writer first boarded her in the Mersey in 1883, she was regarded as the " crack " liner in the Atlantic Ocean service. She was also then the largest and most powerful steamship afloat, with the exception of the unfortunate Great Eastern.

She was also the first Cunarder to be built of steel instead of iron and the first to receive an electric installation. Her length was 515 feet, her beam 52 feet 3 inches, and her depth 40 feet 9 inches.

Her gross register was 7,392 tons, and her engines, indicating 9,900 horsepower, enabled a speed of 16.7 knots on a daily consumption of 190 tons of coal, which reduced the Atlantic passage to 7 days, 1 hour, and 38 minutes. She was superbly fitted and provided accommodation for 480 cabins and 750 third-class passengers.

The Cunard Steamers The Umbria and the Etruria. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 118f3d9e4c

The following additions to the Cunard fleet were the Catalonia, Pavonia, and Cephalonia, which were placed upon the Boston service, and then, in 1883, came a new type of vessel in the Aurania, which, while 45 feet shorter than the Servia, was five feet wider in the beam -- a circumstance which enabled material improvements to be introduced in the accommodation for first-class passengers.

This same year saw the launching of another Atlantic line at the yard of Messrs. John Elder & Co., at Glasgow, of Oregon, whose compound, direct-acting inverted engines developed 13,500 indicated horsepower and enabled a speed of 18 knots to be attained.

This sensational result immediately led the directors of the Cunard Line to order two new vessels from the same builders. While incorporating the best features of Oregon, they had others of their own. Together, these made the Umbria and Etruria, illustrated below, the fastest and finest ships then afloat.

With a gross register of 8,127 tons and engines indicating 14,500 horsepower, a speed of 20 knots was secured. In its time, the Etruria held the Atlantic record for speed, having accomplished the western passage in 5 days, 20 hours, and 55 minutes and the eastern passage in 6 days, 37 minutes.

But Cunard had not yet reached the acme of its trans-Atlantic ambition. In 1892, the Campania and Lucania were launched, and in 1893, the Lucania, which mighty sister vessels are the fastest yet produced from British shipyards.

The dimensions of the Campania (Illustrated Below), which in every essential particular also apply to the Lucania, are these: length overall, 622 feet 6 inches; extreme breadth, 65 feet 3 inches; depth from the upper deck, 43 feet; and gross tonnage, 12,950 tons.

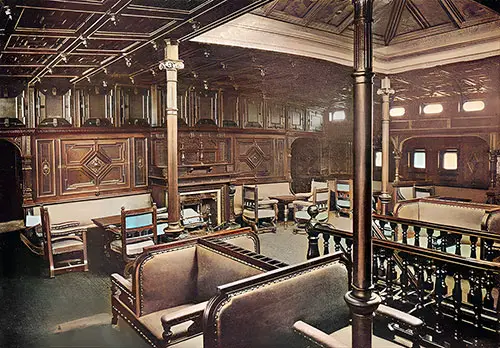

The Saloon Promenade of the Steamships Campania and the Lucania. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 118f55a2e1

The vessel has, to quote technical detail, " a straight stem and elliptical stern, top-gallant forecastle, and poop, with close bulwarks all fore and aft, the erections above the upper deck consisting of two tiers of deck houses, surmounted respectively by the promenade and shade decks.

She appears in fore and aft rig, with two pole masts." In her construction, the greatest care had to be observed to maintain the requisite strength throughout the structure. Every advantage of improved steel sections was taken to secure the maximum strength without unduly increasing the total weight.

The Building of the Cunard Steamship Campania. The Vessel's Skeleton Framework is Shown. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 118f7dedc0

There are sixteen bulkheads in the vessel, and she can float if any two, or in some cases three, are open to the sea. The decks have been strengthened to enable them to carry guns. In other particulars, the Campania complies with the requirements of the Admiralty regarding armed cruisers for service in times of war.

The vital parts of the ship are adequately protected; the steering is of a special type and is under the water line, as are the rudder arrangements. There are four complete decks—the upper, central, lower, and orlop—the first three entirely devoted to passenger accommodation and the last to cargo, refrigeration chambers, storage purposes, etc.

The Grand Dining Salon of the Cunard Steamships Campania and the Lucania. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 118fcd81e2

The Grand Dining Saloon of the Cunarders Campania and the Lucania Showing the Interior of the Dome. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 118feabee8

The entire internal equipment has been based on lines calculated to promote the safety, comfort, and enjoyment of ocean travel. For example, the casings around the boiler rooms are double, and the intervening spaces are filled with material that is a non-conductor of heat and sound.

The ventilation arrangements, both natural and artificial, are the most complete description, as is the sanitary equipment. The " living " spaces are warmed by a system of steam-heated pipes.

The electric lighting installation by Messrs. Siemens & Co. is on a most elaborate scale. Besides a powerful searchlight, four generating plants can supply 1,350 16-candle power incandescent lights—no fewer than 40 miles of wire run through the ship.

The furnishings and decorations of the interior of the Campania are sumptuous and luxurious, having earned the vessel its reputation for being the most palatial and magnificent in the world.

The illustrations may give some idea of the splendor of the appointments. The first-class dining saloon, illustrated above, which will seat 430 passengers at a table, is a superb hall 100 feet long by 63 feet broad.

The general effect of the dark, rich mahogany walls, the graceful arches, and the paneled ceiling in white and gold, surmounted by a great crystal dome (shown at right), rising through the two decks above to a height of 33 feet, and the dark russet velvet upholstery, is most impressive and suggests a palatial structure on terra firma rather than a floating temple of luxury.

The drawing room on the promenade deck (illustrated below) is another sumptuously appointed apartment in the Renaissance style, and its appointments include a delicate organ and grand piano.

The Drawing Room of the Cunard Steamships Campania and the Lucania. The Smoking Room Is Furnished in the Elizabethan Style and Is a Most Popular Retreat Amongst the “Mere Men." (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 11901ce30c

The First Class Smoking Room of the Cunard Steamship Campania As It Appeared Previous to Refurbishing. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 11901e8c86

The Library of the Steamers Campania and the Lucania. The Library Is Another Elegant and Appropriately Appointed Apartment, and the Main Staircase and the Grand Entrance Thereto May Also Be Cited as Examples of the Lavish Scale of the General Decorative Scheme, of the Details of Which Considerations of Space Forbid a More Exhaustive Description. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 119027dcd0

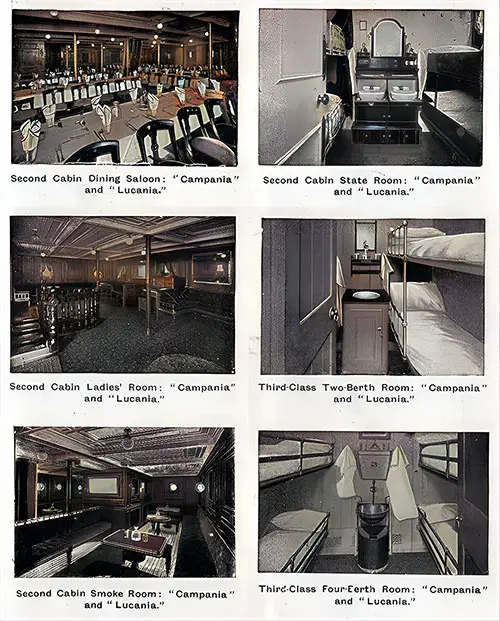

The saloon accommodation on the Campania is situated amidships, the second-class cabins aft, and the third-class accommodation forward. Then, there are some eighty-five second-class state rooms of various sizes besides a handsome dining saloon, an adequately furnished drawing room, and a comfortable smoking room.

Of this accommodation, as well as that which is devoted to the third-class passengers, which is in every respect excellent, and an immense improvement on the sort of thing which constituted the " steerage " of earlier days, several illustrations are given below, which speak for themselves.

The Cunard Steamship Campania, Shown at Sea. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 11902c6c82

Speed, Safety, Comfort and Luxury

Next to safety, the considerations that have chiefly weighed with the Cunard Company are those of speed and comfort, not to mention the luxury and enjoyment of the passengers. Sufficient has been said to emphasize the success that has followed the enterprise and the Company's efforts in these particulars.

Under such auspices, ocean travel has been robbed of the hardships and terrors with which it was formerly associated. In this connection, the stewards' department has all-important functions to serve, and the commissariat of a great ocean liner is a serious business.

The chief steward may have to accommodate 500, 1,000, or 1,500 persons for five, six, or seven days if the weather is fine or for a longer period if it is stormy.

Here is the sort of provisioning which has been made for an average summer voyage of the Etruria, reckoning on 547 cabin passengers and a crew of 287 persons, and, if the figures be increased proportionately, the catering requirements for a voyage on the Campania can be approximated :

- 12,550 lbs. of fresh beef,

- 760 lbs. corned beef,

- 5,320 lbs. mutton,

- 850 lbs. lamb,

- 350 lbs. veal,

- 350 lbs. pork,

- 2,000 lbs. fresh fish,

- 600 fowls,

- 300 chickens,

- 100 ducks,

- 50 geese,

- 80 turkeys,

- 200 brace grouse,

- 15 tons potatoes,

- 30 hampers of vegetables,

- 220 quarts ice-cream,

- 1,000 quarts of milk, and

- 11,500 eggs.

The quantities of wines, spirits, beer, etc., put on board for the round voyage comprise 1,100 bottles of champagne, 850 bottles of claret, 6,000 bottles of ale, 2,500 bottles of porter, 4,500 bottles of mineral waters, and 650 bottles of various spirits.

The Marconi System of Wireless Telegraphy: Instrument Room on Board a Cunarder. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 11906c2bda

A new feature of ocean travel is introducing the Marconi aerial or wireless telegraphy system (Illustrated Above). This system was first used in the Atlantic service on board the Lucania and is now used on the other principal Cunarders as well.

The Marconi signaling station at Nantucket enables steamers to be reported in New York 13 hours earlier than was formerly the case and 11 hours before the old signaling station on Fire Island is sighted.

Records are still being made in ocean telegraphy, but one worth noting was made when, on one occasion, the Lucania passed the Campania in mid-ocean at 11 p.m.

The vessels remained in wireless communication until 5 o'clock the next morning, when they were separated by more than 180 miles! In this connection, the illustration of the instrument room on board the Campania below will be interesting.

The Grand Dining Saloon of the Steamers Ivernia and the Saxonia Showing Interior of the Dome. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 11907a8ad1

Although this article has been chiefly limited to the Cunard Line as a factor in the Atlantic trade, it should be remembered that the Company had a large steam fleet trading between Liverpool and Mediterranean ports.

They own 17 vessels, with an aggregate tonnage of 122,164 tons and about 145,358 horsepower. Despite the vast employment that the building of their new ships afforded in different parts of the country, the Cunard Company found employment for some 6,000 men afloat and ashore.

The administration of the Cunard Company is controlled by a Board of Directors, of which Lord Inverclyde is Chairman and Mr. William Watson is deputy Chairman. The other members are Sir William B. Forwood and Messrs. Wilfrid A. Bevan, Alfred A. Booth, Ernest H. Cunard (a grandson of the founder), M. H. Maxwell, Jr., and John Williamson.

Mr. A. P. Moorhouse is in charge of General management, while Mr. A. D. Mearns and Mr. James Bain, R.N.R., respectively, hold the responsible offices of secretary and general superintendent.

The Company's headquarters are in Liverpool, with the chief offices at 8 Water Street and 1 Rumford Street.

There are also branch offices in London, Manchester, Glasgow, Leith, Queenstown, Belfast, Paris, Havre, Chicago, New York, and Boston, agencies in many of the principal cities and commercial centers of the United Kingdom and the Continent of Europe, and sub-agencies almost everywhere.

And now, in taking leave of the Cunard Line, whose interesting story has been told in brief epitome, it need only be added that the Company owning it proceeds upon its course under the new auspices mentioned at the outset of this article, with vigor unimpaired and resources undiminished.

What the future has in store for the Cunard Line time alone can show, but its prospects may be encouraging. Indeed, its policy will still be progressive, and its traditions will be fully maintained— traditions that add glory to the stirring tale of ocean travel and the interest of romance to the story of THE GREAT ATLANTIC FERRY.

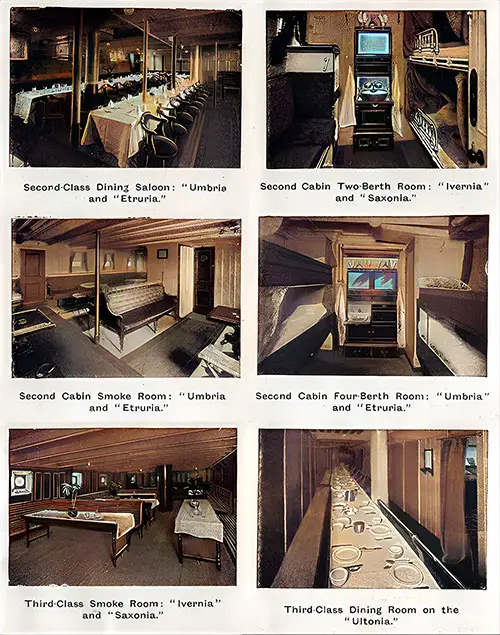

Second- and Third-Class accommodations, occupied by tourists and immigrants alike, are typical of what the passengers found on board the steamships of the Cunard Line circa 1900.

Typical Accommodations On Board the Cunard Steamers

Second Cabin and Third Class Accommodations Typically Found on Cunard Steamships. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 1190b4c422

Image Captions (L to R, T to B)

- Second Cabin Dining Saloon. Campania and Lucania

- Second Cabin State Room: Campania and Lucania

- Second Cabin Ladies' Room: Campania and Lucania

- Third-Class Two Berth Room: Campania and Lucania

- Second Cabin Smoke Room: Campania and Lucania.

- Third-Class Four-Berth Room: Campania and Lucania.

Additional Second Cabin and Third Class Accommodations Typically Found on Cunard Steamships. (Story of the Cunard Line) | GGA Image ID # 1190d08541

Image Captions (L to R, T to B)

- Second-Class Dining Saloon : Umbria and Etruria

- Second Cabin Two-Berth Room : Ivernia and Saxonia

- Second Cabin Smoke Room : Umbria and Etruria

- Second Cabin Four-Berth Room: Umbria and Etruria

- Third-Class Smoke Room: Ivernia and Saxonia

- Third-Class Dining Room on the Ultonia

1902 Brochure of the Cunard Steamship Company

- Date of Publication: December 1902

- Published by: Cunard Steamship Company, Limited - A Reprint of an article apearing in the magazine Business Illustrated.

- Number of Pages (with Text or Images): 33

- Number of Photographs: 13

- Number of Illustrations or Drawings: 26

- Number of Diagrams: 1

⏳ Timeline Highlights & Route Context

Founded: 1840 by Sir Samuel Cunard in partnership with George Burns and David MacIver.

Route Focus: Liverpool ↔ Boston / New York; also Mediterranean service.

Significant Milestones:

🔹 1840 – Maiden voyage of Britannia, marking the birth of modern organized transatlantic travel.

🔹 1850s–60s – Competition from the Collins Line sparks innovation.

🔹 1880s–90s – Introduction of steel hulls, electric lighting, and wireless telegraphy.

🔹 1892–93 – Campania and Lucania launched, becoming the fastest liners on the Atlantic.

🔹 1902 – Government-backed agreement secures Cunard’s British identity for 20 years.

👑 Noteworthy Content & Themes

🔍 Key Themes:

🔹 Technological Leadership – From paddle wheels to screw propulsion, steel construction, and wireless telegraphy.

🔹 State Partnerships – A government loan and subsidy allowed Cunard to remain British-controlled and competitive.

🔹 Innovation in Passenger Comfort – Dining saloons, ladies' drawing rooms, and smoking rooms rivaled European palaces.

📸 Noteworthy Images:

🔹 Sir Samuel Cunard, George Burns, and David MacIver – The trio who laid the foundation of the Cunard empire.

🔹 The Britannia (1840) – Cunard's first ship and symbol of steam-powered revolution 🌊.

🔹 Liverpool Harbor (1837) vs. 1902 – A striking visual transformation driven by Cunard’s success 🏗️.

🔹 The Grand Saloon of Campania and Lucania – A glass-domed hall that seated 430 passengers in opulence ✨.

🔹 Second- and Third-Class Accommodations – Reveals improved steerage conditions, critical for understanding immigrant travel history.

🔹 The Marconi Wireless Room – Marks the emergence of communication-at-sea and safety advancements ⚡.

🎓 Educational Relevance

For Teachers & Students:

A captivating case study in industrial history, British imperial power, and the evolution of travel.

Connects directly to lessons on:

- Immigration and social class

- Transatlantic commerce

- British-American relations

- Technological innovation

For Historians & Genealogists:

Helps trace passenger class distinctions and innovations that impacted immigrant conditions.

Offers rich context for family migration stories, especially through steerage travel.

🧭 Final Thoughts – Why This Article Matters

“The Story of the Cunard Line” is more than a corporate profile; it is a panoramic journey through 19th-century maritime ambition and innovation. From the modest beginnings of Britannia to the glittering triumph of Campania, the Cunard story mirrors the industrial and social progress of the modern world. It is a must-read for anyone seeking to understand how the ocean became a highway of dreams—and how Cunard led the way.

📝 Encourage students writing about immigration, industrialization, or travel to explore the Cunard archives at the GG Archives—your portal to history at sea!

🧳 Set Sail Through History with the GG Archives

🌐 Use this article and many others in the Ocean Travel Collection to bring the past to life in essays, classroom projects, and personal explorations.