The Voyage of the SS Devonshire: An 1855 Passenger Contract & The Harsh Realities of Ocean Travel

📌 Discover the rare 1855 passage contract for the SS Devonshire, a packet ship of the Swallowtail Line. This document reveals the harsh conditions of steerage travel, legal obligations for passengers, and the realities of transatlantic migration in the mid-19th century.

Passengers' Contract Ticket for Fourteen-Year-Old Michail Abrahams on the Packet Ship Devonshire of the Swallowtail Line, Purchased 4 July 1855 for a Voyage from London to New York Beginning on 7 July 1855. GGA Image ID # 208bc5e96f. Click to View Larger Image.

Notices to Passengers (from Left Side of Contract), Three Contingencies, 1. Ship Doesn't Leave On the Designated Date; 2. Passenger Fails to Obtain a Passage (No Room Left); And 3. Passengers Should Keep This Contract with Them Until the End of the Voyage. | GGA Image ID # 208bc7b1c1. Click to View Larger Image.

About the Ship

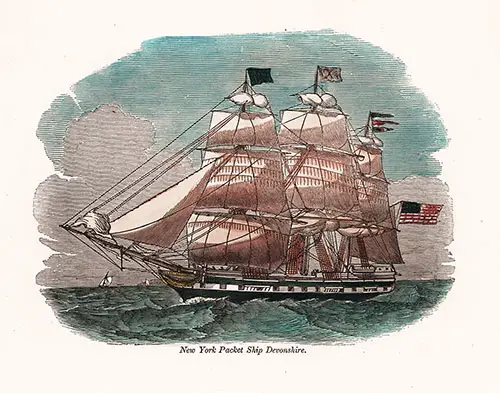

New York Packet Ship Devonshire, 1843. | GGA Image ID # 20a2a03e41

DEVONSHIRE (1843) Swallowtail Line 1,150 tons 3 masts

The U. S. Ship DEVONSHIRE was built at Bath, Maine, by Johnson Rideout in 1843. 745 tons; 148 feet x 33 feet 3 inches x 16 feet 7 1/2 inches (length x beam x depth of hold). The DEVONSHIRE was registered at New York on 7 July 1845.

Some of the Voyages of the Packet Ship Devonshire

- Ship DEVONSHIRE, Thompson, master, arived at New York on 30 April 1845 (passenger manifest dated 1 May), from Liverpool 40 days, with merchandise, to order; 298 steerage passengers. "The D[EVONSHIRE] has experienced severe weather on the passage."

- Ship DEVONSHIRE, Thompson, master, arrived at New York on 9 April 1846 (passenger manifest dated 10 April), from Liverpool 3 (New York Tribune) / 5 (New York Evening Post), with merchandise and 4 cabin and 294 steerage passengers, to S. Thompson. "The D[EVONSHIRE] came out the north channel, and has had very sever weather, sprung the foremast, lost sails, &."

- Ship DEVONSHIRE, Thompson, master, arrived at New York on 5 November 1846 (passenger manifest dated 6 November), from Liverpool 43 days, with merchandise, to the master; 6 cabin and 300 steerage passengers.

- Ship DEVONSHIRE, Strickland, master, arrived at New York on 9 September 1849 (passenger manifest dated 10 September), from Liverpool 34 days, with merchandise and 314 passengers, to Martin Brown. "Sailed in co[mpany] with ship DUBLIN, for New Orleans, and saw her again the 11th August; same time, saw bark SAVANNAH for Savannah."

There were two prominent lines to London, one by John Griswold, consisting in part of the Devonshire, Amazon, Victoria, Hendrik Hudson, Palestine, and Southampton.

Many of these old ships were exceptionally fast sailers, keeping up their reputation for speed after their usefulness had ended in the packet service and they had been transferred to some other trade. On this list should be placed the names of the Roscius, Independence, Henry Clay, John R. Skiddy, Devonshire, Constitution, Marmion, John Bright, Enterprise, St. Denis, New-York, and Admiral.

-- Palmer List of Merchant Vessels

Days of the Old Packet Ships -1891

Contrast Between Present and Past Atlantic Liners

Reminiscences of the Old Passenger Ships -- Most of Them Were Flyers -- Hardships from Which Present Passengers Are Exempt.

New York Times, 13 December 1891.

What a contrast there is between the present facilities for transportation between Europe and America and those of years ago. There are daily departures from either side of the Atlantic of large, well-appointed steamships.

The ocean greyhounds now land passengers at Queenstown, Southampton, or New York within a week from the day of sailing, and the longest transatlantic voyage can be made in a fortnight.

The voyager has a roomy, well-ventilated stateroom and a liberally-appointed table, with liberty to indulge in as many meals as seasickness will allow, the cuisine generally being in keeping with the surroundings and on a par with the current fare at a first-class hotel.

He has plenty of room to move about without coming in contact with his fellow passengers. If he desires privacy, the 300 feet of promenade deck and the limits of his large stateroom permit him to isolate himself.

If, on the other hand, he wants the company to relieve the monotony of a sea voyage, he can always find some friendly fellow traveler among the 500 passengers; in fact, a European voyage today by any of the standard lines partakes mainly of the nature of a picnic.

The great size and power of the present transatlantic steamer make a very long passage almost impossible unless by accident to the machinery. The arrival of many of the steamers can be gauged to hours.

In Winter, when heavy gales are common in the North Atlantic if the sea is not too heavy, twenty-four hours will cover all delays on the voyage. Bound eastward, the strong westerly and northwesterly winds common on this coast in Winter are a potent factor in shortening the passage.

The surroundings of the emigrant on the voyage are far ahead of those on the old packet ships. The saloon passenger has better attendance, luxurious stateroom fittings, and a dainty bill of fare.

Still, the comfort of the steerage passenger is assured by legal restrictions imposed on the vessel. He must have so many cubic feet of room and a proper quantity of wholesome food.

He is debarred from taking his promenade on the quarter deck, but there is lots of room forward on these big steamers, and, take it altogether, he receives a better return for the amount of his passage money than the saloon passenger.

The accommodations for passengers on the old packet ships were much more confined, mainly owing to the smaller size of the vessels. These ships were the best for hull, spars, and letting. Most of them were built in New York by Webb, Smith, & Dimon Westervelt and other old builders on the East River. A few were the outcome of the best builders in the Eastern States.

The cabin was under a poop deck that reached forward to the mainmast. Sometimes, a few feet of the forward part of this deck was partitioned off and made into a second cabin, which was utilized for light freight when not carrying second cabin passengers.

In the first cabin, there were generally twenty staterooms as large as the size of the ship would allow and comfortably furnished. The temporary fittings of the second cabin had little to recommend them other than that the occupants had a table to themselves and were entirely separated from the steerage passengers.

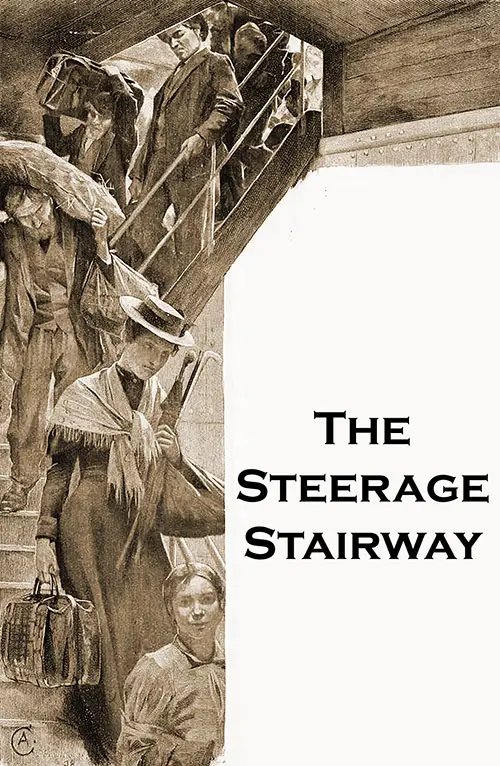

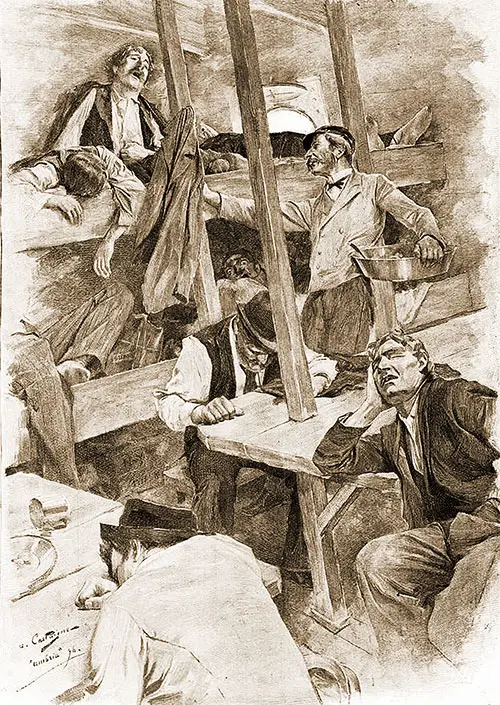

The steerage occupied the whole of the 'tween decks. Single, double, and upper and lower berths were arranged around the ship's sides. Families were placed together as far as possible, and the female passengers were given all the privacy possible in the limited space.

Steerage Passengers Take a Long Stairway into the 'tween Decks. Illustration by J. André Castaigne. Steerage Passengers on the Cunard SS Umbria, January 1897. Published February 1898 Century Magazine. | GGA Image ID # 208bd192ec

The steerage was reached by ladders at the fore and main hatches, which were always open except in bad weather, and ventilators through the deck, and a windsail or two furnished the fresh air to the steerage.

Should the weather become stormy and the sea heavy, the hatches would be closed, and the poor emigrant would have to make the best of his surroundings until the weather moderated.

Steerage in Heavy Weather. Illustration by J. André Castaigne. Steerage Passengers on the Cunard SS Umbria, January 1897. Published February 1898 Century Magazine. | GGA Image ID # 208bf4574a

The number of passengers was limited by law, each vessel being measured by the Custom House authorities, who issued a certificate of the number the ship could carry. The provisions as to quality and quantity were also under legal supervision.

Stringent rules were in force bearing on the cleanliness of the passenger. All possible sanitary precautions were taken to prevent sickness and death during the voyage, with the view of lauding the emigrant here in health and with only the inconveniences inoperable from a long journey in rather confined quarters.

The passage In old times was a very long one at best. Three weeks, either way, was considered a good run, and in the Wintertime, ninety days had been consumed In the western passage.

The ship might reach soundings on our coast and be even within sight of Sandy Hook Lightship when suddenly a heavy northwester might swoop down over the Highlands and drive her before it perhaps hundreds of miles, with the dangerous task before her of beating back again to Sandy Hook against a heavy headwind and a temperature in the neighborhood of zero. Contrast this with today's experience.

The progress made in railroad traveling since the locomotive first appeared is terrific. The European passenger of today who in his youth came to this country in the steerage of one of the old packets can see greater improvement in passenger accommodations now available by any of the European steamers.

The old packet ship reached all the wants of transit in their day. They are no longer a necessity. Progress has put steamers in their place.

In their day, the sailing vessels wore the pride of the New Yorker and a credit to our merchant marine. They were all American. No foreign flag ever flew out of New York at the peak of a packet ship worthy of the name, and no alien vessel over-competed successfully for the trade we have inaugurated and made successful.

Today, we look in vain for an American vessel among the large fleet of fast European steamers. The Ohio and her sister ships that formerly constituted the line from Philadelphia to Liverpool are occasionally heard of as ocean tramps, available for charter to any port where a paying freight is to be had.

Philadelphia had a Liverpool line of line ships managed by the Copes. Boston had a Liverpool line owned by Enoch Train & Co. The firm's senior was the uncle of George Francis Train, who made his first extended trip in his uncle's ship, Anglo-American, under Capt. James Murdoch.

In New York, there was m the Liverpool trade, the Swallowtail Line (so called from the shape of the private signal) of Grinnell, Minturn & Co., comprising, among others, the ships New World, Queen of the West, Henry Clay, Ash Burton, and Albert Gallatin; the Dramatic Line of E. K. Collins, (who afterward operated the Collins Line of steamers,) comprising the Roscius, Sheridan. Siddons, and Garrick; the Black Ball Line, consisting of the Columbia, New York, Fidelia, Montezuma, Yorkshire, Manhattan, Isaac Webb, Harvest Queen, Neptuno, Great Western, and Jamos Foster, Jr., and the Red Star Line of Robert Kermit—the Waterloo, West Point, John R. Skeddy, Constellation, and Underwriter. Woodhull & Minturn ran the Constitution, Liverpool, and Hottinguer; Taylor & Merrill the Ivanhoe, Guy Mannering, and Marmion; Williams A. Guión the Cultivator, John Bright, Australia, and Universe; D. & A. Kingsland, the America, Columbus, Webster, and Orient; David Ogden the St, Patrick, St. George, Racer, Victory, and Dreadnaught; Taylor & Ritch the De Witt Clinton, Enterprise, and Jacob A. Westervelt; Slater, Gardner & Howell the Chaos, Saratoga, Senator, and Jamestown: Samuel Thompson's Nephews Company the Star of the West, Caleb Grimshaw, Excelsior, Joseph Walker, and Jeremiah Thompson.

Those ships, with others, were run at regular intervals and had stated days of sailing, only varied by bad weather or some other unavoidable delay.

There were two prominent lines to London, one by John Griswold, consisting of parts of Devonshire, Amazon, Victoria, Hendrik Hudson, Palestine, and Southampton. Grinnell, Minturn & Co. operated the other line with the Sir Robert Peel, London, Prince Albert, Yorktown, and Rhine.

There were three lines to Havre. Messrs. Boyd &. Heineken ran the St. Denis, St. Nicholas, Oneida, Quesnel, and Mercury. Fox & Livingston had the Havre, New York, Admiral, and Zurich.

Two of the Havre packets, the Iowa and the Duchesse d'Orléans, were selected to carry Stevenson's regiment to California at the time that Territory was ceded to the United States; William Whitlock had In hie Hue the splendid Bavaria, the Helvetia, Germania. Gallia, Logan, and Rattler.

On her first voyage, Bavaria is credited with receiving the highest freight rate paid to Europe during the excitement in rates consequent on the famine in Ireland.

There has been a significant change in the appearance of the West Street and South Street docks since the old packet days. The East River remains the resting place of the bulk of the sailing vessels entering the port.

On the North River, below Twenty-third Street, an occasional schooner can be seen, but never a square rigger. In past days on South Street, William Whitlock's Havre packets berthed near Old Blip, almost opposite his office; E. K. Collins's ships were at the first pier below Wall Street; Griswold's London Line at the foot of Pine Street; Kermit's Line, Grinnell. Minturn & Co.'s London and Liverpool Line and the line of Woodhull & Minturn lay between Maldon Lane and Burling Slip; Marshall's Black Ball Line was at the foot of Beekman Street, while Taylor & Merrill, Williams & Onion, and others filled the piers up to Roosevelt Street and above Peck Slip.

On the North River, the piers from the Battery to Cedar Street, now covered with shade and monopolized by the trunk lines of railroads and one or two lines of steamers, were the berths for many of the lines: Boyd & Hineken's and Fox & Livingston's Havre lines, and David Ogden and D. & A. Kingsland, for their Liverpool lines found room at the piers between those points. Fox & Livingston were situated near Albany Street, the furthest uptown of all lines on the North River.

There was great rivalry between the lines. The fastest ship and the most popular Captain secured the largest passenger list. Full cabins were always assured to certain vessels, while other ships commanded by mon were equally worthy. In every particular, but perhaps a little less pleasant and more "salt," had to be content with second place.

When the steamship lines between here and Europe were first inaugurated, several of the old packet Captains were placed in command of the steamers, in many cases simply because of their popularity with the traveling public.

Capt. West of the Philadelphia packet ship Shenandoah took the Collins steamer Atlantic, Capt. Nye of the Henry Clay took the Pacific, Capt. Luco of the Constellation of the Arctic, Capt. Hackstaff of the Fidelia, the United States, and Capts. Wotton and Lines of the Havre packets took the Fulton and the Arago.

Many of those old ships were exceptionally fast sailors, keeping up their reputation for speed after their usefulness had ended in the packet service and they had been transferred to some other trade. The names of the Roscius, Independence, Henry Clay, John R. Skiddy, Devonshire, Constitution, Marmion, John Bright, Enterprise, St. Denis, New York, and Admiral should be on this list.

The palm would probably be awarded to the Yorkshire of the Black Ball Line for continuous short passages covering the whole time the ship was in the trade. Capt. Bailey, who commanded her, generally managed to keep his ship at the front most of the time, and she was seldom beaten on the passage by a ship leaving at the same time.

Later, when the demand for clipper ships began, John Currier built the Dreadnaught at Newbury port, Mass., and commanded by Capt. Samuels was added to the fleet of Liverpool packets by David Ogden.

Under the command of Captain Samuels, she made some notable passages to and from Liverpool, claiming the record for the shortest passages between the two ports. A peculiarity of this vessel is worthy of note.

After Capt. Samuels gave up the command of the Dreadnaught, and up to the time she foundered, she never made more than a fair passage in any direction and is credited with some quite long ones, worse than the average.

Capt. Nye of the Henry Clay, afterward in the Collins steamer Pacific, claimed to be perfect in everything about nautical matters. One occasion, some unlucky Captain put his ship on Sandy Hook Beach while inward bound.

Commenting on the occurrence, Nye remarked that any man who put his ship ashore within ten miles of Sandy Hook Light was a fool. On his next voyage, the ship Henry Clay went ashore so near to Sandy Hook Lighthouse that you could almost jump onto the lantern from her flying jibboom. After that, Nye did not pose as an instructor in navigation.

Capt. Larrabee of the ship Sir Robert Peel was a perfect sailor and gentleman gifted with quaint abilities at repartee. Once, his ship was lying in the Mersey, outward bound and ready to sail, waiting for the tide and the pilot.

Among the passengers was a young Englishman whose large ideas as to the great superiority of his own country had, so far, never been disputed. He went up to Capt. Larrabee stood by the wheelhouse, earnestly watching the landing stage. The ensign was flying from the peak, and our English friend, after a few commonplace remarks to Larrabee, said, pointing to the ensign :

"Captain, that flag has not braved the battle and the breeze for a thousand years."

"No," quickly replied Larrabee, "but it has licked one that has."

Instances of heroism on the part of the Captains of the old packets are numerous. On one midwinter homeward voyage, the ship John Bright fell in with another" vessel in distress, likewise bound to the westward, and, like the Bright, with a full complement of steerage passengers.

The passengers of the disabled vessel were transferred to the Bright. Ship fever soon broke out and spread rapidly. The overcrowded steerage, lousy weather, and slow progress helped spread the disease.

Death held high carnival, and the Captain was a doctor, nurse, chaplain, and navigator. Helping the ship's doctor, assisting the convalescent, burying the dead, and working the boat was what this team had to do, and he did it well.

After reaching port and docking his ship, the Captain himself succumbed to the disease, and for a long time, his life hung by a thread. He is now filling a responsible position on shore with one of the prominent European lines of steamers.

There were packets from other lines than those to Europe. The coastwise trade, now handled by such fine steamers as ply almost daily to Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans, and Galveston, is carried on by sailing vessels.

The ships Anson, Sutton, South Carolina, and Charleston were In the Charleston line. The Anson and the Sutton were of barely 400 tons. In their day, they transported many a bale of cotton and many a passenger. I have seen their decks filled with cotton, with only space left for the sailors to get around decks to work the vessel.

There were three prominent lines In the New Orleans trade. William Nelson, whose loading berth was at Pine Street, had the Memphis, Vicksburg, St. Louis, and John G. Coster. Frost & Hicks had a loading berth at the north side of Wall Street, where the Ward Havana steamers now lie. They had the Indiana, Niagara, Mediator, Wisconsin, and others.

At the south side of Wall Street was the line of Thomas P. Stanton, comprising, among others, the Quebec, Oswego, St. Charles, and Hudson. The New Orleans packets sailed as often as the trade warranted, semi-weekly or weekly.

They carried large cargoes both ways and made money for their owners. J. H. Brower A Co. had a line of ships to Galveston. Their vessels were built in Connecticut and, owing to the shallow water on the Galveston bar had to be of very light draught. Stephen F. Austin and William B. Travis were part of their fleet. Twelve feet draught, loaded, was the mark for a Galveston packet in those days.

There were lines to Savannah, maintained by Sturges, Clearman & Co., R. M. Demill, and Dunham & Dimon; Mobile was reached by the Hurlberts' ships, and there was intermittent service to Apalachicola and other Gulf ports. Hargous & Co. monopolized the Mexican trade, employing fine vessels running to Vera Cruz.

The old business houses inaugurated and developed to such enormous proportions our foreign and coastwise trade have líkewise faded from sight. A walk through South and Front Streets from Counties Slip to Dover Street does not result in finding the old signs on the stores and offices today.

Howland & Aspinwall, Grinnell, Minturn & Co., Josiah Macy's Sons, and James W. Elwell & Co. are about all that is left. The present members of these firms wore boys when the packet lines existed.

The old sailing ship was pushed to the wall by the steamer. Today, the significant improvements in steam machinery, securing significantly increased speed with less fuel expenditure, are forcing many considered perfect steamers into the rear rank not long ago.

The Algiers and the New York of the Morgan Line are now extra boats, functional in emergent cases, but need to be faster for the regular service. Ships like the El Sol, El Mar, and El Monte, who can make the trip to New Orleans in less than five days, are what is wanted.

In the Galveston trade, we Added the Concho and the Comal, replacing the City of Dallas and the State of Texas. The Kansas City and the City of Birmingham replace boats like the K. B. Cuyler and Knoxville in the Savannah trade.

The Yucatan and the Yumuri are better adapted to the Havana Line than the old Moro Castle, and even on the daily line to Boston, the wants of the trade demand the substitution of steamers like the Herman Winter and H. F. Dimock for the old Glaucus and Neptune.

It has been satisfactorily demonstrated that the United States can build and equip steamers equal to any afloat in their adaptability to the wants of our domestic commerce. May the time be near when the American flag will be seen at the peaks of steamers in the European trade!

"Days of the Old Packet" New York Daily Times, Dec 13, 1891 p. 17

Recap and Summary: Passage Contract Ticket – SS Devonshire (7 July 1855) 🚢📜

A Rare Window into Mid-19th Century Transatlantic Migration

The Passengers' Contract Ticket for Fourteen-Year-Old Michail Abrahams on the SS Devonshire, purchased on 4 July 1855, for a voyage from London to New York beginning 7 July 1855, offers a remarkable historical snapshot of transatlantic migration during the height of the packet ship era. The Swallowtail Line, known for its fast and reliable packet ships, operated the Devonshire, a vessel that transported hundreds of passengers—mostly immigrants—on arduous multi-week journeys across the Atlantic.

For teachers, students, genealogists, and historians, this document serves as an invaluable artifact, providing insights into 19th-century ocean travel, migration policies, and the economic conditions shaping the journeys of those seeking a new life in America. It also offers a comparison between early transatlantic sailing and the later era of steamships, highlighting the evolution of maritime travel and immigration trends.

📜 Key Voyage Details

Date of Purchase: July 4, 1855

Date of Departure: July 7, 1855

Passenger: Michail Abrahams (14)

Ship: Packet Ship Devonshire

Line: Swallowtail Line

Route: London → New York

Voyage Class: Steerage (Lowest Class)

Contract Terms: Passenger regulations, liability clauses, and travel conditions outlined in detail.

Noteworthy Notices:

- Ship Departure Contingencies – If the ship was delayed, passengers had specific rights.

- Passenger Limitations – If the ship was fully booked, those who could not be accommodated were refunded.

- Ticket Documentation – Passengers were required to carry the contract until arrival, indicating that contracts were used for accountability and legal documentation.

This contract reflects the highly regulated yet unpredictable nature of 19th-century sea travel, when sailing schedules were subject to weather, ship conditions, and the realities of long ocean voyages.

🌍 The Historical Context – The Packet Ship Era

The mid-19th century was a transformative period for transatlantic migration, with millions of Europeans seeking opportunities in the United States. Packet ships, like the Devonshire, were sailing vessels operating on fixed schedules, distinguishing them from other cargo ships that waited until they were full before departing.

📌 Why This Document is Historically Important

The Swallowtail Line was a major player in the Liverpool and London-to-New York trade, competing with famous lines like Black Ball, Red Star, and Collins Line.

Packet ships were the primary means of migration before the dominance of steamships, making this contract an important artifact of an earlier migration era.

The steerage experience aboard these ships shaped the early immigration journey, influencing later legislation and improvements in passenger accommodations.

This document provides first-hand evidence of the regulations and contractual obligations for immigrants, many of whom were traveling under difficult economic conditions.

🚢 About the SS Devonshire – A Veteran of the Atlantic

The Devonshire, a 1,150-ton, three-masted packet ship built in 1843, was part of a fleet of fast, reliable vessels that transported both cargo and immigrants across the Atlantic.

📌 Notable Voyages of the Devonshire

The Devonshire's service record, as documented in newspapers, highlights its challenging crossings and the harsh conditions faced by passengers:

- April 30, 1845 – Arrived in New York from Liverpool after a 40-day voyage, with 298 steerage passengers. Severe weather was reported.

- April 9, 1846 – Another stormy crossing, causing damage to the ship’s foremast and sails.

- November 5, 1846 – Arrived in New York after 43 days at sea, carrying 300 steerage passengers.

- September 9, 1849 – Completed a 34-day voyage from Liverpool, carrying 314 passengers and experiencing severe weather.

These reports underscore the extreme unpredictability of 19th-century ocean crossings—passengers could face delays, storms, and ship damage, all while being crammed into steerage quarters with minimal provisions.

📝 The Passage Contract – A Look at 19th-Century Immigration Travel

📑 Key Contract Terms & Notices

This passenger contract ticket includes several critical clauses that illuminate the realities of steerage-class travel:

- Ticket Validation & Refund Policies

- If the Devonshire was delayed beyond its scheduled departure, passengers had the right to rebook or receive compensation.

- If the ship was full, passengers who failed to obtain passage were refunded—highlighting the high demand for transatlantic migration at the time.

- Passengers were advised to keep their contract until arrival, emphasizing its importance as proof of passage.

Steerage-Class Conditions & Passenger Rights

- Limited space in steerage, with tight, overcrowded conditions for the poorest passengers.

- Strict food rationing, with many passengers required to bring their own provisions.

- Crude sanitation and hygiene, with few regulations ensuring cleanliness or comfort.

Legal Regulations & Passenger Safety

Packet ships were legally bound to provide adequate provisions and space, though in practice, conditions varied.

The contract detailed legal disclaimers protecting the ship from liability for delays, injuries, or unexpected events.

This contract is a vital document for understanding early ocean travel, illustrating the financial, logistical, and regulatory challenges immigrants faced in their quest for a new life.

📸 Noteworthy Images & Their Significance

🖼️ Passenger Contract Ticket (1855)

A rare and detailed legal document, providing proof of passage and outlining contractual obligations.

Essential for genealogists researching family migration history.

🖼️ New York Packet Ship Devonshire (1843)

A depiction of the ship that carried thousands of immigrants across the Atlantic.

Highlights how sailing ships were gradually replaced by steamships, transforming immigration patterns.

🖼️ Steerage Passengers in the ‘Tween Decks

A stark portrayal of the overcrowded, poorly ventilated steerage conditions.

Illustrates the hardships of ocean travel for lower-class immigrants, making this a powerful historical artifact.

🖼️ Steerage in Heavy Weather

A dramatic image showing the dangers of sea travel, as steerage passengers struggled to survive storms and rough seas.

Provides historical context for the risks and hardships faced by early immigrants.

🔍 Why This Document is Valuable

📚 For Historians & Teachers

Illustrates the economic and social conditions of 19th-century migration.

Provides a real-world example of how migration was legally structured.

👨👩👧👦 For Genealogists

An essential record for tracing immigrant ancestors.

Provides insights into the travel experiences of 19th-century European immigrants.

🌎 For Students & Researchers

Demonstrates the impact of maritime advancements on migration.

Shows how 19th-century transatlantic voyages shaped U.S. immigration history.

🌍 Final Thoughts: A Journey of Hardship and Hope

The 1855 passage contract for the SS Devonshire is more than just a piece of paper—it’s a testament to the dreams, struggles, and endurance of thousands of immigrants who left everything behind for a new life in America. This document paints a vivid picture of transatlantic migration, from the rigid regulations to the grueling conditions of steerage-class travel, making it a priceless historical artifact. 🚢📜✨

/1855-07-07/1124-PassengersContractTicket-500.jpg)

/1855-07-07/NoticesToPassengers-LeftSideOfContract-500.jpg)