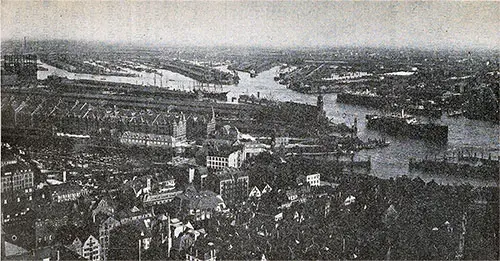

Port of Hamburg, Germany

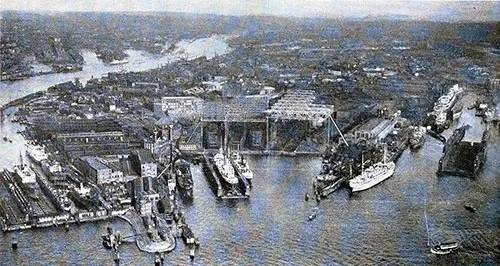

General View of the North End of Hamburg Harbor. | GGA Image ID # 1425e97838

Hamburg, the most significant port in the German Republic, stands out with its annual commerce, surpassing the combined total traffic of all other German seaports. What sets Hamburg apart is not just its greater volume and value of trade, but also its diversified and widespread nature, unmatched by any domestic rival.

The port's ascent to the pinnacle of the world's greatest entrepôts is a testament to the strategic decisions made by successive administrations, who deftly harnessed a combination of political and economic factors.

The city early procured political freedom from the hampering influence of selfish and greedy overlords. As a self-governing city-state, it could devote its entire energy to encouraging trade and enlarging or improving the natural strategic advantages with which nature had endowed it.

Recognizing the imperative necessity that the Elbe be kept open to the fleets of the world if commerce were to flourish, the city gained control of the river and, at a time when “robber barons” were exacting exorbitant tolls on other waterways, permitted shipping to traverse this estuary unmolested.

Political autonomy became necessary when the separate Germanic States were amalgamated into the German Empire. Hamburg readily entered the body politic, but it determinedly resisted the pressure to join the Zollverein or customs union since raising a customs barrier would undoubtedly have been detrimental to its transshipment trade and specific industries established there.

By using its previous political status and its obvious importance to Germany as a wedge, it was able to force a compromise for a free-port zone, a concession that has been of prime importance in the port's growth.

Hamburg's geographic location is a boon that few ports in Europe can match. Nestled near the mouth of the Elbe River, it provides an unparalleled medium of communication with the densely populated and highly industrialized zones of central Europe, forming the heart of its hinterland.

Five main lines of the German National Railway radiating from the port serve to augment the traffic lanes provided by the inland waterway system and make contact with points in the tributary area not otherwise accessible.

The rail lines supply express service to practically all parts of the Republic and, through connecting foreign lines, with other countries of central and southern Europe.

Because of these rail and water connections and the low rates that prevail, Hamburg is able to compete favorably with Mediterranean and Channel ports in territory that might otherwise be considered entirely tributary to the latter.

Its proximity to the Baltic and Scandinavian countries, which interchanges hundreds of thousands of tons of cargo annually, is the prime factor in developing its extensive transshipment traffic.

Hamburg has become the center of this trade principally because it is the nearest ocean port of major importance with direct services to the world's markets. This nearness is enhanced by the Kaiser Wilhelm, or Kiel, Canal, which intersects the Jutland Peninsula at the mouth of the Elbe and lowers passage time between the North and Baltic Seas by about 24 hours.

A discussion of the port of Hamburg would be complete only if it mentioned the spirit of cooperation between private interests and port officials.

In a State-owned and managed port, efficiency is expected in the operating personnel, but the esprit de corps at Hamburg extends beyond the state employees and includes all the private operators, such as the stevedores, bargemen, draymen, warehousemen, tugboat companies, steamship lines, freight forwarders, and others.

The spirit of cooperation between state and private interests, where all work together to advance the port's interests, is a shining example of unity and collective effort.

The cohesion of the many different organizations and the suppression of personal interests for the good of the whole are worthy of the highest commendation.

Hamburg considers that its future lies in the port, and everything is subordinated to its welfare.

The government and regulation of the port are vested in the Senate, which has, in turn, delegated its authority to several separate boards, each of which supervises one of the port's principal functions.

All matters of policy or recommendations of profound purport are brought before the Senate, whose decisions are final and without appeal. Since the entire harbor area is the property of the State, no private interests can balk projects promulgated for the good of the community as a whole.

Port charges are maintained at as low a level as possible and are predicated principally upon the wage scale of port labor. All receipts from port operations are turned over to the State treasury, which budgets all of the city's expenditures. The State meets any deficit in the harbor's operating costs through deficiency appropriations.

No attempt is made to profit from actual port operations, as port costs must be reduced to a minimum to permit competition with Rotterdam and Antwerp, both of which have cheaper labor and are assisted directly or indirectly by their national Governments.

Hamburg's succession of efficient administrators, gifted with foresight, have shown remarkable resilience in overcoming the chief obstacle in the path of international prominence—the lack of space for expansion.

Then, too, the choice of the open-basin method of construction, in preference to the closed-dock system, has proved of inestimable value, for only with the unhampered movement of ships independent of the vagaries of the tide could the limited space available be used to its utmost efficiency.

One of the fundamental causes for the growth of Hamburg's commerce is the intense industrial and agricultural development of that portion of its hinterland accessible by inland waterways.

Manufactured products find their egress to world markets, and imported raw materials are transported to interior industries through the medium of the Elbe, its tributaries, and connecting canals, which serve the southern, central, and western portions of Germany.

However, the wealthiest industrial areas of Germany, namely, the Rhine, Ruhr, and Saar Walleys, are not now connected by inland waterways with this greatest of German outlets.

The bulk of the products originating in these latter areas, destined for foreign consumption, pass out through the ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam. It is believed abroad that if there were a cheaper means of transportation than by the rail lines connecting these centers of the industry with the Elbe ports, both the Rhine Valley and German North Sea ports would profit considerably.

Location

The port of Hamburg, situated in the northwestern part of Germany on the Elbe River about 65 miles from its mouth, is part of the Free City of Hamburg, one of the States comprising the German Republic. The state's area is approximately 160 square miles, of which the city occupies about 52 square miles, the remainder being divided into three smaller municipalities and 28 rural districts.

This area includes the Ritzebuettel district, at the mouth of the Elbe, which contains Hamburg's outport, Cuxhaven. The State of Hamburg is surrounded by Prussia, with the portion on the northern bank of the Elbe, which is by far the largest, bounded by Schleswig Holstein, and that on the southern bank by Hannover. The population in 1928 was 1,208,439, of which 1,127,834 resided in the city of Hamburg.

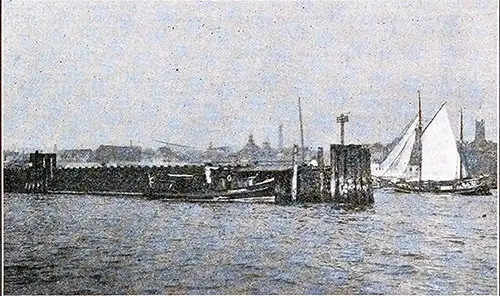

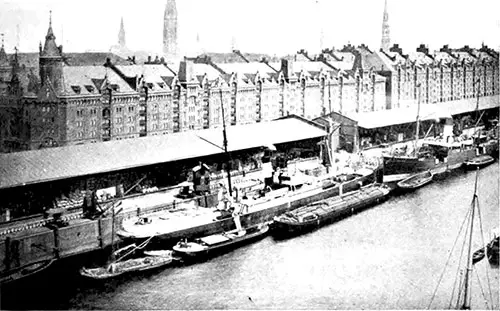

View of the Hansahafen, Port of Hamburg, Germany. | GGA Image ID # 1425eff21c

ENTRANCE CHANNEL AND APPROACHES

The Elbe River affects the entrance to the port. A vessel approaching the mouth of the river will first sight, in order, the four light vessels: Elbe I, or outer light vessel, Elbe II, Elbe III, and Elbe IV, all of which are painted red with their names on their sides.

These lights indicate the channel between the Scharhorn Riff, Neuwerker Watt, Kleiner Vogelsand, and Steilsand on the south side of the entrance and the Grosser Vogel, Gelbsand, and Hakensand on the north side.

The river, which almost forms a figure S between Cuxhaven and Hamburg, is easy to navigate. The channel is well marked with the uniform German system of red spar buoys with letters on the starboard and black conical buoys with numbers on the port.

The river, between the sea and Cuxhaven, has a navigable depth of about 37 feet at high water neap tides and about 26 feet at low water spring tides.

Between Cuxhaven and Hamburg, the minimum depth is 25 1/2 feet at low-water spring tides, which rise from 7 1/2 to 11 feet. The channel is now being deepened to 40 feet at mean high water. Its width ranges from 660 to 1,300 feet.

The German government controls the maintenance of the river. In 1921, after the port of Hamburg spent approximately $40,000,000 on improvements, it was relieved of that responsibility.

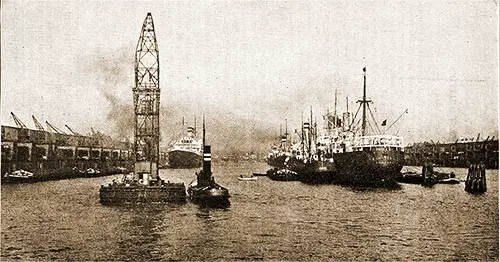

General View of Hamburg Harbor. | GGA Image ID # 142602ac6b

THE HARBOR

The harbor of Hamburg comprises several open sub-harbors or basins excavated from the banks of the river. These

basins are divided into two classes—those for ocean-going vessels

and those for barges and other river and harbor craft.

The barge harbors virtually surround the deeper draft harbors, and they are connected to them and each other through locks and canals.

In most cases, the channels of communication between them and the

deep-water basins are separate and apart from the entrances frequented by ocean vessels, thus limiting the possibility of accidents and expediting the flow of traffic by increasing the flexibility of interchange.

The port is divided into two main sections: the free port and the customs port. The former contains all the deep-water harbors, with the exception of the coal harbor (Kohlenschiffhafen), the Maakenwärderhafen, and a portion of the Niederhafen.

It also contains the following barge harbors and connecting canals: Ilugenbergerhafen, Rodewischhafen, Travehafen, Spreehafen, Saalehafen, and Moldauhafen. The remainder of the barge harbors, together with the yacht harbor (Jachthafen) and the two basins mentioned above under the free port, comprise the customs port.

Section of the Floating Customs Barrier at the Port of Hamburg. | GGA Image ID # 1426f3cb19

The entire port, including free and customs ports, is again divided into four zones for administrative purposes. Within these zones are numerous districts whose names evoke the time when the south bank and its adjacent islands were utilized for agriculture.

The total water area of the port is approximately 1,965 acres, of which the deep-water basins, including the yacht harbor, contain 1,250 âcres. The water frontage on these basins is approximately 30 miles, and practically all have been developed to accommodate ships.

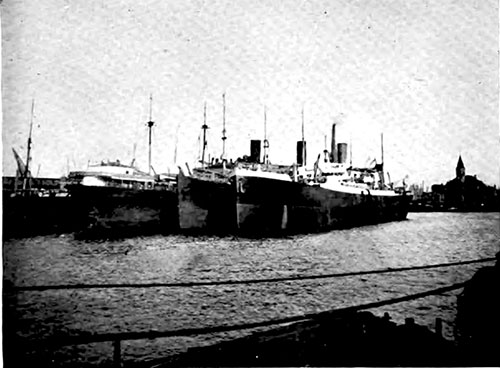

Ships in a Basin in Hamburg Harbor. | GGA Image ID # 1427a2870a

FERRIES

Numerous passenger ferries traverse the various parts of the harbor. They form one of the principal means of communication between the residential portion of the city on the north bank and the harbor facilities and industrial district within the free port on the opposite side of the river.

The only car ferry in the port is the one that crosses the Koehl brand, connecting the Ross-Neuhoff district with the Waltershof district. Due to a treaty with Prussia, no bridge can be built across this waterway, and consequently, this ferry is the sole means of linking the rail systems of the main portion of the port with the facilities in the Waltershof district.

The two vessels which are operated in this service are peculiarly adapted for use on this waterway in that they are completely symmetrical with twin screws at both ends, thus precluding the necessity for turning around when approaching their slips. Each can accommodate six railroad cars and other vehicular and passenger traffic. They are also constructed to cope with the changes in water levels because of tide fluctuations.

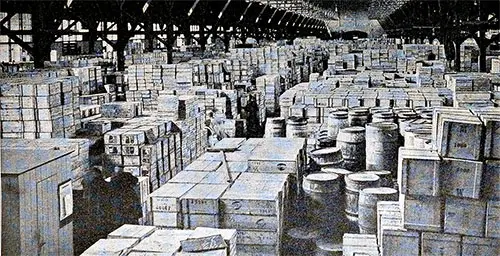

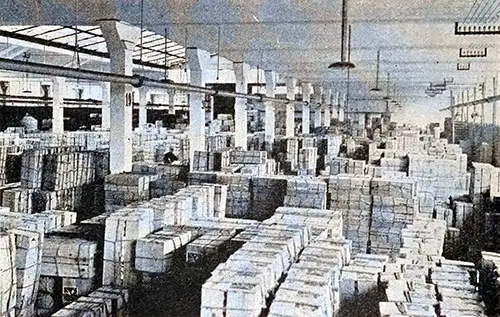

Interior View of a Quay Shet of the Hamburg-American Line at the Port of Hamburg. | GGA Image ID # 1427c56d72

THE ELBE TUNNEL

The Elbe tunnel, which was opened to traffic in November 1911 at a cost of $2,550,000, connects the north bank of the river at the St. Pauli Landing Stages with the industrial district in Steinwarder. Because both entrances are located in intensely utilized areas, inclined approaches to the tunnel were practicably impossible; instead, two shafts, each 72 feet in diameter and 77 feet deep, were sunk to meet it.

Each shaft is equipped with six electric elevators, two of which have a capacity of 10 tons, two of 6 tons, and two of 2.4 tons each. The two last named are used for passenger traffic and the other four for vehicles.

The tunnel, 1,470 feet long from shaft to shaft, is divided into two tubes, one serving northbound and the other southbound traffic. Each tube has a roadway 6 feet wide, bordered on each side by walks 4 3/4 feet wide.

When ice or heavy fog impedes ferry traffic, the tunnel is closed to vehicular traffic during rush hours. At these times, as many as 70,000 people can utilize it in one day. Pedestrians are not charged; vehicles pay according to a set schedule.

Interior View of Fruit Shed "C" at the Port of Hamburg. | GGA Image ID # 14281ff2e8

The Port Captain’s Office

The port captain's office supervises the entrance and clearance of all ships and is responsible for preventing and alleviating all congestion in the harbor. The port captain has four subordinate harbor masters, one for each previously described zone.

Each harbor master is responsible to the port captain for allocating berths to ships not using the quays, the pilots and pilotage of vessels in his area, the movement of all river and harbor craft, the superintending of lights and buoys within his area, and the distribution of customs signals.

The port captain's office has nothing to do with cargo handling except that which passes over the Johannesbollwerk and Vorsetzen Quays, which are within the customs boundaries.

At these two quays, it collects wharfage and craneage charges on portions not leased to private concerns. It also collects fees for using the St. Pauli landing stages.

View of Hamburg Harbor Showing Shipbuilding Activity. | GGA Image ID # 14283c4614

THE POLICE DEPARTMENT

Another intermediary office, the police department, is in charge of maintaining order within the port. Formerly, the duties of patrolling the water and bridges were exercised by the so-called “Blue police.”

Since the war, however, several companies of barrack police have been installed in the port to quell extraordinary disturbances and prevent pilferage. A sub-office of this department is the harbor inspection office, which carries out the regulations to prevent accidents.

THE SANITARY OFFICE

The sanitary office enforces the harbor regulations relating to sanitation and quarantine.

CUSTOMS

Since Hamburg has an extensive “free port,” customs and customs regulations have little control over ocean shipping. This is particularly true because ocean-going ships, except those engaged in coastwise traffic and those carrying coal, cannot discharge or load cargo outside the free port.

The free port is guarded by high-wire fences on the land side and floating palisades on the waterside. Boats patrol the openings in the palisades. Craft leaving the free port must stop at the customs control offices stationed at every entry into the customs territory, where they are subjected to close surveillance by the guards.

A similar operation takes place on trucks and trains passing the customs barrier. To expedite the movement of large ships, all pilots are sworn customs officers charged with seeing that the vessel over which they have control does not carry on illicit trade along the shore on the trip up or down the Elbe.

This precludes the necessity for customs inspection and the sealing of hatches upon entry and clearance. Barges entering or leaving the port with cargo in bond coming from or destined to bonded warehouses in Germany or for a foreign country must be sealed or carry a customs inspector with them.

The cars are sealed on similar shipments by rail before they leave the free port.

Ships leaving one portion of the free port and passing through customs territory to reach another portion of the free port and vessels entering or clearing with a pilot must fly the black and white diagonal customs flag so that the customs patrol will not stop them.

QUARANTINE REGULATIONS

Quarantine officials are available to ships between 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. Special arrangements must be made for ships entering outside these hours. All vessels arriving at Hamburg or lying in the harbor are subject to the inspection and surveillance of the sanitary office, as provided for by the sanitary regulations.

Persons suffering from epidemic diseases, as well as fever, cholera, leprosy, and scurvy, may leave the ship only after inspection by the sanitary officers and with their permission. The ship's captain must notify the sanitary office of all internal diseases that may have developed during the port stay. The harbor police will take charge of these notices.

The signals used for summoning doctors or police in the event of sudden illness or accident on board a ship in the harbor are: By day, the usual distress signal, consisting of a flag hoisted on an upright pole or a large sheet fastened to it, with its free ends tied into a knot or fastened together with cords, to prevent it from fluttering freely; at night, continuous, rapid ringing of the ship's bell, repeated at short intervals; also, if possible, three white lights grouped together.

The captain of the ship or a member of the crew appointed for that purpose must furnish all official information requested by the sanitary officers when the latter make their inspection. All cases of death and illness that occurred during the voyage and all diseases still present on arrival at the harbor or that developed during the ship's stay must be reported.

Sanitary officials are authorized to disinfect, vaccinate, and carry out all other measures they deem necessary in the interest of public health. The same regulations apply to the order and cleanliness, ventilation, heating, and arrangement of the crew's quarters and to food and drinking water.

Ships flying a yellow flag from the foremast, in conformity with the regulations regarding the control of the sanitary police authorities over a ship entering Hamburg, must not be boarded.

IMMIGRATION

Immediately upon arrival in the port, the captain of every inbound ocean vessel must submit to the proper police officers a list showing separately the members of the crew, passengers who are not subjects of the German Government and do not have a passport and a German visa—i.e., stowaways, deported persons, persons working their way, and those without funds.

Persons without passports with a German visa will not be permitted to land until authorized by police officials. If any persons on board are not of the white race, the document must include this information.

The ship's captain is not permitted to land persons, not German subjects, who are or will be discharged in Hamburg except when authorized by the proper police authorities.

All persons permitted to land may come ashore at any time during the ship's stay in the harbor. The officials in charge of port entries will issue the necessary instructions regarding the stay of undesirable persons.

The latter are placed provisionally under the surveillance of the superior officers of the ship. The vessel's captain and undesirable passengers will be given a written order prohibiting the latter from landing.

If the ship's officers agree to transport undesirables back to their home ports, the police must be notified immediately. The police must also be notified promptly of all deserters and other persons who have landed without permission.

The captain must promptly report any person leaving the ship against the orders of the police or leaving the ship ahead of the specified time to the proper police authorities.

If any non-German subject violates the stipulations of his passport or the police regulations, the shipowner must reimburse the expenses incurred in boarding, apprehending, and deporting the violator and give security as specified by the proper police authorities.

Discharged passengers who are not German subjects are permitted to stay in Hamburg only after the ship's officers or the steamship company have deposited the sum necessary for transportation back to their home ports and when there are no other objections to the stay of such passengers. Otherwise, these persons must not be permitted to land, and the ship's officers will be instructed to transport the undesirables back to their homes on board the same vessel.

For every non-German passenger who has landed without permission and is missing on departure, the captain of the ship must deposit as security the sum of 100 marks, together with an additional amount equal to the average cost of the return transportation.

The sum remaining, after deducting all incidental costs and fees from the total amount, will be reimbursed after evidence has been submitted that the missing person has left Germany.

In the case of vessels touching Hamburg regularly, the nature of the security to be furnished may be regulated by agreement between the police authorities and the steamship company or its agent.

Violations of these provisions are punishable by a maximum fine of 150 marks or imprisonment for six weeks, in conformity with the harbor law, unless the general penal laws provide more significant penalties.

General Local Regulations

The port's official hours are 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. The following holidays are observed: New Year’s Day, Good Friday, Easter Monday, Labor Day (May 1), Ascension Day, Whit Monday, the third Wednesday in November, and December 25 and 26.

The following regulations relating to ships in Hamburg harbor are excerpts from the harbor law and its amendments:

All vessels and craft in the harbor are subject to the provisions of the harbor law and its supplementary regulations and to the ordinances of the port authorities and harbor police.

They are also subject to existing customs regulations and all subsequent ordinances made by the customs officials when within the customs harbor.

Vessels alongside the quays administered by the State are subject to the ordinances of the quay officials in conformity with the provisions for using the quays.

The regulations for using the public landing stages and the instructions of officials and employees in charge must be observed.

SPEED OF VESSELS

Steamship Captains must ensure that other vessels are not endangered by the wave movements caused by their ships. In the harbor district north of the Elbe, steamships are not permitted to move under full steam except during ice jams.

Steam-driven vessels must slow down when passing steam dredges, diving bells, pile drivers, and salvaging vessels. They should pass only on the side on which such vessels show a red ball by day and a red light over a white light by night.

DISPOSAL OF RUBBISH AND WASTE

Rubbish and waste on board ships must be segregated into combustible and incombustible materials. Combustible waste must be delivered to the garbage barges near the south bank of the Norderloch.

Incombustible, such as ashes and slag, must be delivered to certain storage areas on the bank and deposited as directed by the overseer near the anchoring place of the garbage vessels. Rubbish on ships must be moistened to prevent the spread of dust before it is collected and removed.

It is prohibited to throw or let fall into the water any rubbish, waste, or other substances that might pollute the harbor or obstruct navigation. When loading and unloading ballast or other loose substances, tarps or similar devices should be used to prevent polluting the harbor.

BERTHAGE PREFERENCE

At quays with sheds, steamships will be given preference over sailing vessels, and those steamships that belong to lines operating regular services to and from Hamburg, using the quays regularly, will be given preference over other ships. The ships of these lines will be assigned the same berths as far as possible. According to the commercial code, a master may berth at a quay at his customary loading or unloading place.

LANDING STAGES

Much of the communication between the residential portion of the city and the free port is by boat, which necessitates the use of landing stages at all quays in the deep-water basins.

These stages had to be constructed to cope with the fluctuation in water levels. In some places where the traffic is not great and where only small vessels ply, landing stairs leading to the lowest water level have been built, and in some instances, iron pontoons and floating platforms are placed before these stairs.

Where traffic is brisk, particularly at the points used by ferryboats, this method needed to be improved; hence, movable bridges, supported by rollers on floating pontoons, were constructed. The slopes of these bridges depend upon the level of the tide.

The most important of these stages are the St. Pauli landing stages located on the north side of the Elbe, approximately opposite the Blohm and Voss shipbuilding yard.

Several more miniature stages are combined into a larger one, approximately 1,400 feet long and 66 feet wide. Its surface rises six feet 4 inches above the water level. At its rear are waiting for accommodations, offices, luggage rooms, shops, and restrooms, while on the dome above is a tall clock tower equipped with a tide gauge indicating the water level in the harbor.

The eastern part of these landing stages carries an upper deck 660 feet long where passengers can be discharged from the promenade deck of ocean-going vessels.

COAL-BUNKERING FACILITIES

Hamburg's importance as a coal-bunkering station increases yearly, owing to the large number of lines calling at the port and to the fact that it is usually the last port of call for many ships.

English coal, Durham unscreened I and II, and West Hartley predominate the market in Hamburg. However, Westphalian unscreened is also primarily used.

A price agreement exists for lots of 200 tons or less, whereas the market is open for larger quantities.

Due to the great extent of the harbor and in an effort to speed up a vessel's turnaround, practically all bunkering is done overside from barges by means of mechanical grabs and bunkering machines.

This accommodation eliminates the necessity for a ship to change berth and move alongside a coal-bunkering station. Methods of delivery vary considerably.

Quantities of up to 250 tons are delivered in donkey barges equipped with winches and hoisting baskets. This method bunkers 200 to 250 tons for an 8-hour shift.

The number of baskets is counted, and the average weight of coal per basket is ascertained; from this, the amount of coal delivered is determined. The donkey barges are primarily owned by firms trading in coal and companies specializing in coal bunkering.

Many of the shipping companies that have vessels calling regularly

at Hamburg buy coal in barge lots.

Special bunkering devices with automatic weighing appliances bunker large quantities of coal. Some of these machines can bunker from both sides of a ship simultaneously, and their bunkering capacities run as high as 225 tons an hour; trimming and shifting of coal in barges reduces this to 150 and 175 tons an hour. The three principal companies that specialize in the bunkering of coal are the Kohlenheber, G. m. b. H., the Kohlenstaurei,

G. m. b. H., and Reinecke & Bremer. The second-named firm is engaged principally in the discharge of colliers. It has machines that operate at 250 to 300 tons an hour.

Sauber Gebr., which deals in British coal, operates about 50 barges for bunkering purposes and has machines that can bunker 120 to 150 tons an hour. This company's coal is stored in the Kohlenschiffhafen, where about 10,000 tons of coal are usually maintained.

Another important coal-handling concern is the Schiffahrt und Kohlen G. m. b. H. This company typically maintains 10,000 to 15,000 tons of coal, stored partly in the Kohlenschiffhafen and partly in barges in the Travehafen. This company operates 35 barges with a capacity of about 200 tons each.

The Raab Karcher-Thyssen G. m. b. H. handles both English and Westphalian coal, particularly the latter. It maintains about 15,000 tons of coal and operates 102 barges with an approximate capacity of 15,000 tons.

The Westfälishes Kohlenkontor Naht, Emschermann & Co. has a large storage plant in the Kohlenschiffhafen where 15,000 to 20,000 tons of coal are usually stored. This company operates several donkey barges and owns 120 lighters with capacities varying from 100 to 250 tons each. Two or three days' notice is required to deliver 500 tons of bunker coal. The code address is Kohlenkontor.

The Kohlen-Koksund Anthracit-Werke can supply English bunker coal at their plant on the Reiherstieg, equipped with cranes and grabs, with a discharging capacity of approximately 4,000 tons in 18 hours.

The Hamburg-American Line has a bunkering elevator for coaling large trans-Atlantic liners. This machine can handle coal up to 65 feet above the water level and can bunker on both sides of a large vessel without shifting.

OIL-BUNKERING FACILITIES

The principal oil-bunkering facilities are in the Petroleumhafen and on Bubendey Ufer, on the south bank of the Elbe adjacent to the Petroleumhafen.

This basin, which was opened in 1914, has a water area of approximately 3,300,000 square feet and adjacent land of about 4,600,000 square feet for storage tanks, pipelines, and pumping houses.

The length of the quayage in the basin is 7,055 feet. The Bubendey Ufer has two piers with a depth of approximately 40 feet at mean high water, which permits the larger ocean liners to come alongside.

Despite the fact that these facilities are available, much of the oil bunkering in the port is done by barges, making it unnecessary for ships to shift berths and increasing the rapidity of turnaround.

THE PORT OF CUXHAVEN

The port of Cuxhaven, which lies on the south bank at the mouth of the Elbe about 64 miles below Hamburg, comprises a considerable part of the Ritzebuettel district, a detached part of the Free State of Hamburg. It is not equipped for handling overseas commerce to any great extent but is utilized principally as a depot for overseas passengers and as a center for the fish industry.

It is also used as a harbor of refuge and as a pilot, signaling, and

quarantine station.

Although the port is very old, it was used comparatively recently for something other than a harbor of refuge. Hamburg obtained the Ritzbuettel district in 1394, but no effort was made to develop a port there until a plan was evolved to utilize Cuxhaven as an embarkation and disembarkation point for overseas passengers and as a base for the deep-sea fishing industry in the North Sea.

The principal obstacles to constructing a harbor for ocean ships were the encroachment of the Elbe and the sea and the silting of dredged areas. The latter is still a serious problem, as the river deposits as much as 10 feet of silt per annum despite the fact that an extensive system of dikes and retaining walls has been constructed.

The harbor now has a total water area of 151 acres, of which 1474 acres are available for ocean vessels. The total quayage in the port amounts to about 14,245 linear feet, of which 12,275 feet have sufficient depth to accommodate ocean vessels. Most of the water area is included within three basins: the Amerikahafen or Neuehafen, the Fischereihafen, and the Altehafen. The Amerikahafen in its entirety and parts of the Fischereihafen and Altehafen have been designated as a free zone, the total area of which is about 130 acres with approximately 8,807 linear feet of quayage and mooring berths.

The largest basin in the port is the Amerikahafen, which covers about 100 acres. It was constructed to accommodate the largest passenger ships in the Hamburg trade. At low water, it was deepened to 40 feet, but owing to the war, it was never used for this purpose.

Due to silting, the present depths in this basin range from 15 to 24 feet at low water. An attempt has yet to be made to reestablish the 40-foot depth, as it was found that large ships could be berthed at Glueckstadt with as much safety and at much less cost. At present, this basin is used as a refuge by small craft, fishing vessels, and salvaged ships.

The Lentz quay, which forms its northern side, has five 3-ton electrically operated cranes. Still, these are used only for salvaging operations, as little cargo is handled in the port.

The Fischereihafen, or “fishery harbor,” is the busiest portion of the port. It is about 3,200 feet long and ranges from 160 to 500 feet in width. Six fish sheds, used for unloading and handling fish, have been constructed on the south bank.

Except for shed No. 3, these sheds are 500 feet long and 65 feet wide. They are all two-story buildings, with the ground floor containing packing and refrigerating rooms and the second floor used for offices and storage.

Behind these sheds are three auction halls, one hall for every two sheds, where the catches are auctioned off. The quays of the basin are of concrete, and ships of 20 feet draft can be berthed at them. Mechanical equipment on the Fischereihafen consists of one 3-ton crane on the south bank and 17 electric winches.

The only other basin of any importance is the Altehafen, in which the depth is about 13 feet at low water. It is used for the general accommodation of vessels.

Overseas passenger steamers discharging or receiving passengers at

Cuxhaven berth at the Landungshöft, or “landing stage.” This facility is more than 1,200 feet long. It is situated on the Elbe on the point of land separating the Amerikahafen and the Fischereihafen.

Immediately behind it are the customs examination halls and the new railway station connected by covered gangways.

The tidal range at Cuxhaven is greater than at Hamburg, the normal range being 9 feet 6 inches. The greatest variation recorded was 27 feet 6 inches. Weather conditions are about the same as in Hamburg. However, due to its proximity to the North Sea, the weather at the mouth of the Elbe is less changeable.

Being a part of the Free State of Hamburg, the harbor is under the jurisdiction of the committee for trade, shipping, and industry, except the Fischereihafen, which is managed by the Fischmarkt G. m. b. H., a firm founded to handle the marketing of fish, the stock of which is owned entirely by the State of Hamburg. All harbor dues and regulations in force at Hamburg also apply at Cuxhaven.

The only company in the port capable of supplying bunker coal is the Westfälische Kohlenkontor, which can furnish up to 1,000 tons. This company's premises are on the Lenzkai, where vessels up to 5,000 tons can be berthed.

No facilities are available for docking seagoing ships aside from fishing trawlers. Bugsier, Reederei & Bergungs A. G. maintain a salvage station and two salvage tugs at the port.

The larger of these is the Seefalke, a vessel of 570 gross tons equipped with oil engines capable of developing 4,200 horsepower. This craft is the most modern of this company's extensive fleet and is fitted with modern appliances.

Aside from receipts and fish shipments, Cuxhaven's commerce is negligible. In 1927, receipts from Hamburg and smaller ports on the Elbe below Hamburg totaled 27,322 tons, of which 10,341 tons were general merchandise and 16,981 tons were bulk cargo.

This tonnage was entirely for local consumption. Receipts of fish during the same year amounted to over 43,000 tons, while the number of overseas passengers arriving and departing was 22,696 and 34,615, respectively.

Port of Hamburg: Regaining Pre-War Trade (1922)

One of the most significant features of the present shipping situation in Europe is the prosperity and activity visible in the port of Hamburg. After becoming almost a dead port during the war, Hamburg is once again itself and today is certainly the busiest port in Europe.

The continental editor of the "Liverpool Journal of Commerce" recently examined the port and was struck with its comparative prosperity compared to the other ports of Europe. Not only are the four large shipbuilding yards working with full staffs, building vessels of all sorts for Germany and other countries and repairing many British vessels, but the shipping trade in the port is expanding daily. The quay and warehouse accommodation are being extended to meet the new requirements of increased traffic and cargo.

Before the war, Hamburg was a German port. Today, it is cosmopolitan. The American element is very predominant in shipping circles, and the German flag is still crowded out by those of foreign nations. Incidentally, Hamburg companies are making some very useful combines with the home countries—notably the United States.

Hamburg Is not crippled like so many continental ports by being under the control of the municipality. It is administered by a special port committee of shipping and businessmen known as the Deputation for Handel Schlffahrt and Gewerle. Geographically, the port is now in the best of positions, and its prosperity is due to the special port committee's enterprise.

Although Hamburg is about sixty miles up the River Elbe from the North Sea, the condition of the river is so good that ocean liners can easily use the port. Furthermore, the Elbe is deep enough on the inland side of Hamburg to permit steamers of 1,000 tons to run as far as Prague in Bohemia. This gives Hamburg a big ocean trade and an important river trade from Central Europe. The Kiel Canal allows Hamburg to retain a good share of the Baltic trade.

There are now nearly twenty miles of quays where large ocean-going ships can be accommodated, and the entire extent of the port covers an area of 10,000 acres. As one sees it today, the port is only about thirty-five years old. The Segel-Hafen dock is 1,51S yards long and 328 yards wide. The docks of the port have ninety miles of railway line.

Figures for the last year show more ships using the port of Hamburg than the two river ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam. In 1913, the shipping tonnage in the port totaled 22.000.000 tons. The port officials, in view of the present political situation, are not in a hurry to publish figures, which may show big totals for 1921, but unofficial estimates show the traffic for last year to be equal to prewar trade.

Hamburg Harbor Developments (1922)

The Senate of Hamburg has now published the comprehensive petition that It addressed to the Reichsrat (Federal Council) last September regarding the extension of the harbor's area and the creation of a Greater Hamburg. The preamble states that the matter concerns the maintenance of the harbor's competitive capacity in relation to foreign world ports.

According to the Frankfurter Zeitung, the petition points out that the area of the harbor district was extended from 72 acres to 3,100 acres during the 40 years between 1874 and 1914. Notwithstanding this expansion, the harbor is inadequate to meet the requirements of ocean shipping, while the existing area of the State of Hamburg does not offer sufficient space for the necessary extensions of the port.

It is mentioned that the total tonnage of Hamburg shipping traffic in August 1921 reached 78.3 percent of the total traffic in the same month in 1913. The present extent of the traffic already renders necessary a rapid extension of the harbor installations because of the increased accommodation required by the transshipment traffic and the growth in the staple traffic.

The merchandise traffic with Czechoslovakia has given the transshipment trade a new impetus, and it is expected to increase further.

The industrial district in the harbor also plays a great part in the matter. The state area no longer offers the possibility of establishing industrial works on sites where deep water accommodation for ocean ships is available, and as a consequence, a number of applications for promising undertakings have had to be refused.

As a special matter, attention is drawn to the pressing necessity for providing housing accommodation for harbor workers, the number of whom is expected to increase considerably in the future.

The territory that the State of Hamburg desires to incorporate within its area to proceed with the contemplated developments, it is stated, would increase the total area by about 483 square miles or practically double the State territory at present. For this purpose, Prussia would need to surrender large portions of Storman, Piuneberg, Jork, Harburg, and Luxemburg districts to Hamburg. At the same time, Hamburg's population would be raised from 1,000,000 to 1,500,000.

The only question now to be settled is whether Prussia will feel disposed to adopt a sufficiently accommodating attitude in the matter as to permit the significant expansion in shipping and industrial works, which is in contemplation at Hamburg.

Pre-War Prosperity Returning to Hamburg (1922)

At present, the mark is the prime factor upon which trade revival in Europe is concentrated. The countries of Europe are financially interdependent, and there has never in history been a more striking demonstration of the artificial value of money than that presented by Germany's position in Europe today.

The majority of other European countries are suffering from trade slumps, which accompany unemployment and dead markets, while Germany is working in a crescendo towards its pre-war prosperity, only hindered by its inability to purchase raw materials.

A visit to a port like Hamburg is illuminating. In Hamburg, there are no working classes. All classes are at work, and the directors are usually harder than anyone else. The continental editor of the Liverpool Journal of Commerce, who has recently been visiting some of the leading shipyards, was frequently invited to meet the management at 8:30 a.m. Their working day continues until 7 p.m.

Talking with them means being informed not only of the minute details of their own works or industries but also of the industrial development of Germany as a whole.

The spirit of the combination is far more marked than in England and America, where combine usually refers to a trade union organization. Though trade unions exist in Germany, there is far less feeling of output restriction because one class does not have the idea of being exploited at another's pleasure.

Hugo Stinnes' recent expression on this subject was that labor had the right to obtain from any industry all that that industry could afford. This is surely proof that the work people are satisfied that they are getting this treatment, when one considers the way men like Stinnes moved about unprotected and unmolested during the Revolution of 1918.

The masters do not spare themselves, and the men do not spare themselves. If the mark recovers, Germany will be able to buy raw materials to continue its great industrial output. Her high output will help her keep production prices low, and due to the exchange, she has gained a great market through her low prices.

American Line Terminal In Hamburg (1922)

AN AMERICAN steamship terminal of the most modern type will be erected in Hamburg, Germany, built with American capital, equipped with American machinery, and used exclusively by American steamers.

Adjacent to the Hamburg American piers, the American terminal will excel in equipment and efficiency. It will be rated as the finest in Germany. It will be built on the Ross Quay, one of the largest dock structures in Hamburg that remained incomplete at the beginning of the war, and the American Line has taken a long lease. It will have a total length of nearly half a mile, with a depth of water alongside to accommodate the largest passenger liners now operated in the American Line's service from New York.

Sheds will be built of concrete and steel, 656 feet long, and have a ground floor area of 2 1/4 acres. The latest type of electric cranes will be installed. Trackage will connect the terminal through rail lines. American products will be moved to interior points in Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and other Central European countries. The ships that will use this new terminal are now docking temporarily at piers secured on hire from the civic authorities of Hamburg.

In pursuance of its policy to establish itself permanently in Hamburg, the American Line has bought a building in the steamship section for its own occupancy as German headquarters and has sent an American steamship expert, Mr. Hennan Winter of New York, as resident manager.

The American Service, which was thus established in Hamburg, was the first to open direct passenger and freight communication between the United States and Germany following the war. The first ship on the route, the Manchuria, left New York on December 20, 1919, with passengers and a huge cargo of foodstuffs for the famished Germans. The Manchuria has continued to operate, with well-filled holds and cabins, on the Hamburg run ever since, with a sister ship, the Mongolia.

Recently, the 17,000-ton British-built liner Minnekahda was transferred to the American flag and will be added to this service to carry third-class passengers. This ship will be ready in March when a schedule of fortnightly sailings by the three large combination freight and passenger vessels will be adopted.

The service's distinctly freight fleet in the past year has included two 12.000-ton American-built cargo carriers of the latest type, the Montana and the Montauk, which were purchased from the Shipping Board for this service, and a number of other freighters.

The business of the line is steadily growing in volume, says President Franklin.

The Port of Hamburg (1909)

Interesting View of Hamburg. | GGA Image ID # 1441e525c6

"Few ports in the world, if any, are equipped to handle merchandise more expeditiously and economically than Hamburg, despite a situation 75 nautical miles from the open sea.

For many centuries, the local government has made keeping its port facilities abreast of the commercial requirements of the times its first concern. In so doing, it has even assumed the responsibility and cost of dredging and lighting the entire lower Elbe, although only a part of its shores is within the territory of this State.

The free City of Hamburg received a charter from Frederick Barbarossa on May 7, 1189, guaranteeing the right of free navigation on the lower Elbe, and upon this celebrated charter repose all subsequent claims to entire independence, which have been waived by the City only to the extent of enabling it to become a complete and sovereign member of the Empire.

During Napoleon's fleeting occupation of Hamburg, he contemplated strengthening the City's commercial resources by building a canal from Luebeck on the Baltic to the Elbe and other canals connecting the Elbe, the Weser, the Ems, and the Rhein.

All of these canals, with the exception of the one from the Rhein to the Ems, now form part of Germany's great interior navigation system. This system, together with Hamburg's position on the North Sea, facilitates commerce with the whole of northern and central Europe, of which this City is the center.

A Partial View of the Free Port of Hamburg. | GGA Image ID # 144287c491

Upon the entrance of the State of Hamburg into the German customs union, it became necessary to subject all goods entering the city for consumption to the payment of the same duties as were collected in other portions of the Empire.

To accomplish this result and preserve the freedom of centuries for its growing trade, the most important section of the harbor was set aside as an immense bonded warehouse within which goods might be landed, stored, manufactured, and re-exported subject to no custom control whatsoever.

Within this zone, complete commercial freedom prevails, and it is only when goods from the Free Harbor pass the boundary line for immediate consumption that they become subject to the payment of German duties.

Thus, Hamburg remains a protectionist city in its capacity as a member of the Empire while preserving its status as a free city in respect to its extensive transit trade.

PORT CHARGES AND FACILITIES

View of Sandtor Bay, Hamburg. | GGA Image ID # 144299b6f6

The maximum water depth in Hamburg Harbor is 25.82 at low water and 32.8 feet at medium-high water. The maximum draft of vessels at present is about 31.16 feet. Steamers of any size may enter the port at ordinary high tide, including draw 30 feet.

Numerous dry docks, including one believed to be the largest in the world, patent slips, shipbuilding wharves, and engine works, enable ship owners to affect any repairs.

The quays are equipped with cranes that can lift loads to 150 tons, loading and unloading machinery, railroad tracks, and other modern appliances to discharge cargo quickly.

Harbors for river craft and convenient means of transferring cargoes from seagoing to river and coastwise vessels exist now and are being greatly improved.

View of the Harbor of Hamburg. | GGA Image ID # 1442b1b845

During the winter, mighty ice breakers keep the channel open so that ships can always proceed up and down the river.

Merchandise is loaded and discharged either alongside the quays or amid the stream. In the former case, according to a tariff of quay dues referred to below.

Bulk cargoes are continuously discharged and loaded in the river. In contrast, mixed cargoes are commonly discharged on the quay to obtain quick dispatch. Steamers with general cargoes often discharge in the river. Still, the operation is necessarily slower than when the vessels are alongside, owing to the necessity of assorting packages according to marks and numbers and shifting lighters.

When ships load from the quay side, the cargo is taken from the quay shed by the quay cranes and put into the ship, or vice versa. If the operation is performed in midstream, the ship's winches perform this work.

Busy Scene in Hamburg's Harbor. | GGA Image ID # 1442b332e5

Sailing Ship Harbor at Hamburg. | GGA Image ID # 1442e9e384

For the discharge of loose grain, ten floating pneumatic elevators are available, each capable of discharging 700 to 800 tons per day out of one hatch. Thus, 3,000 tons can be discharged in one day if four elevators are employed.

The expenses incurred by a vessel in the Hamburg Harbor depend upon the cargo, whether or not quays are used, and the private charges of various persons who furnish their services.

Stevedores, barge owners, and shipbrokers charge private charges, regarding which official information cannot be given.

Tonnage dues are charged to all vessels, but quay dues only to those that discharge alongside the quays.

Powerful Half-Arch Cranes of About 3 Tons Capaciy, and Two-Story Sheds. | GGA Image ID # 1443a28bcc

The auxiliary vessels for sea-going ships in use in the port of Hamburg can be divided into three classes :

1. Barges generally used for transporting merchandise on inland waterways of 300 to 1,800 tons loading capacity, used chiefly for transporting grain and bulk articles taken over directly out of the sea-going ship to all points on the upper Elbe and Bohemia. These barges are built flat, broad, and long. Their draft is about 3.3 feet.

Freights are charged according to offer and demand; they fluctuate considerably, chiefly based on the Elbe water level, particularly the upper Elbe. In severe winters, ice interrupts river traffic on the upper Elbe.

2. Iron lighters with a loading capacity of 180 to approximately 1,000 tons, crews permanently living on board, and loading appliances of their own—mast, lighter beam, and winch.

These are used to transport goods to all points along the lower Elbe and the Baltic, utilizing tow boats. Because the lower Elbe (below Hamburg) has been improved by dredging so that vessels drawing more than 30 feet of water can reach the Port of Hamburg without being obliged to lighter previously, it seldom happens nowadays that vessels lighter part of their cargo at Brunshausen, the most favorable lightering point on the lower Elbe.

3. Steel barges, used to transport goods from ship or dock to warehouse or factory, are employed under an extremely complicated tariff.

Steamers arriving with cargoes of grain discharge exclusively by floating elevators directly into barges lying alongside, generally midstream.

Resin, turpentine, and cotton steamers are also discharged exclusively midstream, directly into harbors or rivercraft, chiefly because of the danger of fire. Vessels arriving with general merchandise from New York, Montreal, and other United States and Canadian Ports discharge their cargo almost exclusively upon the docks (quays).

The consignee of the goods may forward such merchandise by rail, lighter, or rivercraft. Carts remove Smaller quantities from the quays and transport them to their destination.

In the harbor of Hamburg, an extensive service of lighters and harbor barges is maintained. About 500 covered and 2,500 open barges, totaling 3,000 vessels with loading capacities ranging from 20 to 500 tons, are available.

Hoisting Crane Lifting About 20 Tons. | GGA Image ID # 1443ca3153

THE HAMBURG FREE PORT AND WAREHOUSE

The Free Port of Hamburg is a city within itself. It includes, as already explained, that portion of the city within which customs laws are ineffective. The state owns and governs it as an immense and complicated bonded warehouse, which has permitted many manufacturing establishments to locate there to obtain special shipping facilities and the free use of imported raw materials.

The Free Port territory consists of 2,508 acres, of which 785 acres are underwater. This territory is divided from the city proper by the Lower Harbor, the Inner Harbor, the Zoll-Canal, the Upper Harbor, and the Upper Harbor Canal.

The Free Port boasts an extensive infrastructure. More than 13.7 miles of stone quays surround the various docks, both within and outside the Free Port. These docks are equipped with ten fixed and 631 movable cranes, with an additional 111 cranes located in various buildings or attached to them, demonstrating its capacity to handle large volumes of goods.

Ships from Every Clime Can be Seen in Hamburg's Harbor. | GGA Image ID # 14444009b8

50 sheds with a storage area of 4,090,320 square feet are used for temporary goods accommodation. Railroad tracks behind the sheds facilitate the prompt and convenient discharge of merchandise by land.

The most important feature of the Free Port is the system of warehouse buildings, which, for purposes of administration, belong not to the State but to the Hamburg Free Port Warehouse Company, a corporation chartered by the State and in which the State itself holds a large block of stock.

The State of Hamburg decided to enter the German Customs Union and create a Free Port to preserve its overseas trade. Thus, it became necessary to decide whether the necessary warehouses located within the Free Port should be under State or private control.

The latter course was chosen, and the North German Bank of Hamburg was authorized to set up a stock company on March 7, 1885, under terms made and agreed upon with the city's financial department.

The buildings were erected upon public land in the Free Port, and the Company was authorized and required to issue warrants transferable to order or in the name of the bearer for goods stored on this property.

The stock capital was fixed at $2,142,000, and the contract regulated the tariffs to be charged for the storage and manipulation of merchandise.

Crowded Section of Hamburg's Harbor. | GGA Image ID # 1444daa907

The State of Hamburg placed 322,930 square feet of building ground at the disposal of the Company and undertook to erect the necessary quay walls and slips in exchange for a share in the operating company's net profits.

In addition, a portion of the company's net profits is set aside each year to create a fund for the state to acquire the Company's stock so that eventually, upon the acquisition of all the shares in the operating company, the State itself will become a full proprietor.

To supply the ground space agreed upon, the 16,000 people residing on the island of Kehrwieder Wandrahm were obliged to seek new homes.

The Board of Supervising Directors consists of nine members to whom are added three persons representing the City. The managing directorate consists of two or more members of the general board.

Busy Scene In Hamburg's Docks. | GGA Image ID # 1444e24ccb

The original warehouses have been greatly expanded and improved since the Free Port opened to traffic. All of the buildings have land and waterfront and are divided into single fireproofed divisions, which are let out to business houses of all nationalities.

A great many American firms have warehouse accommodation within which, at times, millions of dollars worth of American goods are in storage or are in processes of manipulation for re-exportation to the various markets easily accessible from Hamburg.

Until January 1, 1910, 1,161,069,624 square feet of land were covered by warehouse buildings, within which there were 5,417,725,716 square feet of storage accommodation.

Of the total storage accommodation, 3,186,972,828 square feet were leased to particular firms, while the remaining 2,230,752,888 square feet were administered by the Company in its capacity as a storage Company.

Sailing Schedules That Include the Port of Hamburg

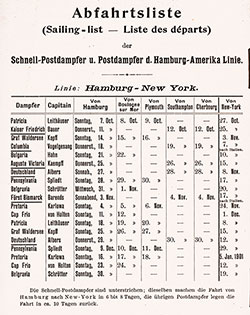

Hamburg American Line (HAPAG) Sailing Schedule, 7 October 1900 to 19 January 1901

Steamers and Ocean Liners operated by the Hamburg Amerika Linie / Hamburg American Line (HAPAG) were scheduled for transatlantic voyages between 7 October 1900 and 19 January 1901.

Bibliography

United States Department of Commerce and United States Shipping Board, The Port of Hamburg Including the Ports of Altona and Cuxhaven, Foreign Port Series No. 1. Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1930.

"Hamburg: Regaining Pre-War Trade," in Shipping: Marine Transportation, Construction, Equipment and Supplies, New York: Shipping Publishing Co, Volume 15, No. 5, March 10, 1922, p. 44.

"Hamburg Harbor Developments," in Shipping: Marine Transportation, Construction, Equipment and Supplies, New York: Shipping Publishing Co, Volume 15, No. 4, February 25, 1922, p.44.

"Pre-War Prosperity Returning to Hamburg," in Shipping: Marine Transportation, Construction, Equipment and Supplies, New York: Shipping Publishing Co, Volume 15, No. 2, January 25, 1922, p. 46.

"American Line Terminal In Hamburg," in Shipping: Marine Transportation, Construction, Equipment and Supplies, New York: Shipping Publishing Co., Inc., Volume XIII, No. 2, January 25, 1921, P. 69.

Frederick L. Ford, "The Port of Hamburg." In Part II: A Study of Some Representative European Ports in the Summer of 1909, Report of Connecticut Rivers and Harbors Commission to the General Assembly, Hartford: State of Connecticut, 1911, P. 65-71