The Inman Line: Pioneers of Transatlantic Travel – Passenger Lists, Ship Histories & Legacy

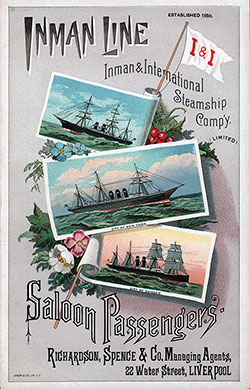

The Inman Line Steamship Company was established in 1850 and operated until 1885, when the American Line and Red Star Line purchased the assets.

When liquidated, The Inman Line was reported to have made little or no money for a long time. This was primarily because there were too many steamships in the transatlantic passenger service.

They also lost several ships—the City of Boston in 1870 and the City of Brussels in January 1883. A few months later, the Inman Line Pier burned. In 1885, the Inman Line fleet consisted of the City of Chicago, the City of Richmond, the City of Chester, and the City of Berlin.

Inman Line Royal Mail Steamers Ephemera

1877-04-21 SS City of Brussels Passenger List

- Steamship Line: Inman Line

- Class of Passengers: Saloon

- Date of Departure: 21 April 1877

- Route: New York to Liverpool

- Commander: Captain Frederick Watkins

1881-10-18 SS City of Chester Passenger List

- Steamship Line: Inman Line

- Class of Passengers: Saloon

- Date of Departure: 18 October 1881

- Route: Liverpool to New York

- Commander: Captain Frederick Watkins

1883-10-25 City of Chicago Passenger List

- Class of Passengers: Saloon

- Date of Departure: 25 October 1883

- Route: Liverpool to New York

- Commander: Captain Robert Leitch

1884-06-05 City of Berlin Passenger List

- Class of Passengers: Saloon

- Date of Departure: 8 June 1884

- Route: Liverpool to New York

- Commander: Captain Arthur W. Lewis

1884-09-02 City of Chester Passenger List

- Steamship Line: Inman Line

- Class of Passengers: Saloon

- Date of Departure: 2 September 1884

- Route: Liverpool to New York

- Commander: Captain Henry Condron

1884-10-25 City of Chester Passenger List

- Steamship Line: Inman Line

- Class of Passengers: Saloon

- Date of Departure: 25 October 1884

- Route: New York to Liverpool via Queenstown (Cobh)

- Commander: Captain Henry Condron

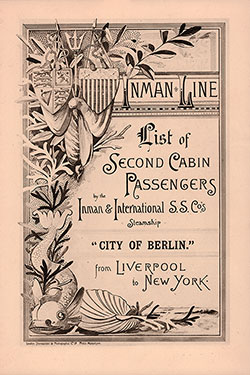

1889-09-11 SS City of Berlin Passenger List

- Steamship Line: Inman Line

- Class of Passengers: Second Cabin

- Date of Departure: 11 September 1889

- Route: Liverpool to New York

- Commander: Captain Francis S. Land

1892-06-04 SS City of Chester Passenger List

- Steamship Line: Inman Line

- Class of Passengers: First Cabin

- Date of Departure: 4 June 1892

- Route: Liverpool to New York

- Commander: Captain F. M. Passow

The Story of the Inman Line (1896)

William Inman was a native of Leicester, England, born in 1825 and became a clerk in the office of Richardson Brothers, Liverpool. In January 1849, he became a partner. He managed a fleet of sailing packets trading between Liverpool and Philadelphia.

Thus, Mr. Inman gained an intimate knowledge of the emigrant business. He was a man of high energy and universally respected.

Although the SS Great Britain, the first ocean screw steamship, had been a marked success, few had as yet much faith in the screw. One of the few was the late David Tod, of the firm of Tod & McGregor, of Glasgow, shipbuilders and engineers.

The SS City of Glasgow (1850) of the Inman Line. History of the Anchor Line, 1911. | GGA Image ID # 1d28dbe221

In 1850, he decided to try the experiment of running iron screws to New York with goods and steerage passengers and launched the SS City of Glasgow.

She was 1610 tons gross, 227 feet long, with a 32-foot beam, and had a nominal 350 HP. This was the commencement of the third "Epoch," leading to great results.

Mr. Inman watched her progress with great interest. After several successful trips, he persuaded his partners to buy and run her to Philadelphia. She sailed from Liverpool under her new owners, commanded by B. R. Matthews, formerly of the SS Great Western.

On 11 December 1850, Mr. Inman formed the "Liverpool, New York, and Philadelphia Steamship Company," which, as he became its general manager, became better known as the "Inman Line."

She was successful, and Mr. and Mrs. Inman traveled across the Atlantic, especially to study the wants and discomforts of steerage emigrants. 1851, a larger ship, the SS City of Manchester, was added.

She was also built by Tod & McGregor, as were most of the Company's subsequent ships. She was 274 x 38, 2125 tons gross, and 400 HP nominal. She was so successful that she is said to have left a profit of 40 percent on her first year's work.

The line soon became especially popular with emigrants, carrying more third-class passengers than any other. In 1857, the line was transferred to New York, and in the two years 1856-7, the Company carried no less than 85,000 passengers!

Between 1851 and 1856, they added the SS City 0f Philadelphia, 2189 tons; the SS City of Baltimore, 2538 tons; the SS City of Washington, and the SS Kangaroo, all iron screws, and in 1857 they commenced calling at Queenstown. This remarkable success quickly led to the formation of many other lines of screw steamships in the United States and Canada.

In 1856, no less than three new lines were established, the "Allan," the "Anchor," and the "Hamburg-American "; in 1857, the "North German Lloyds," and in 1859, the "Galway" line. Except for the last-named ones, all were successful and went to the Clyde for their ships.

The owners of the American sailing packets fought hard for the emigrant business but finally realized that the struggle was hopeless and gradually sold their ships to British, Norwegian, Canadian, and German ship owners.

However, it was not until 1874 that they finally ceased to carry emigrants. Americans could not build iron screws as cheaply as the British could, and their antiquated navigation laws forbade their ship owners to buy British-built vessels.

In 1860, the Inman Company increased its service to once a week, three times a fortnight in 1863, and twice a week in summer in 1866. After the collapse of the "Collins" line in 1858, they assumed the latter's days of sailing and carried the United States mail.

When the Cunard line gave up the Halifax route, the Inman Company contracted to carry the mail to and from that port and did so for many years until the Allans secured it. The Company built many fine ships in the Clyde to carry out these services.

The SS City of Bristol had 2655 tons and 350 HP, the SS City of Boston, and the SS City of New York. In 1863, the SS City of Limerick had 2536 tons and 250 HP, and the SS City of London had 2765 tons and 450 HP.

In 1865, they bought the SS Delaware and renamed her the SS City of New York, 3499 tons and 350 HP (the second of that name). In 1866, they built the SS City of Paris, which had 3081 tons (346x40x26) and was of much greater power, 550 nominal.

In 1867, they built the SS City of Antwerp, 2391 tons and 350 HP; in 1869, the SS City of Brooklyn, 2911 tons and 450 HP; and the SS City of Brussels, 3747 tons (390x40x27) and 600 HP. In 1872, they ventured on larger ships and built the SS City of Montreal, 4451 tons and 600 HP.

The SS City of Paris was their fastest boat. In 1869, she made the passage from Queenstown to Halifax in 6 days 21 hours, the quickest on record between the two ports at that time. In 1870, the Company carried 3635 saloon passengers and 40,635 steerage passengers to New York, more steerage than any other line. The Cunard Company carried 7638 saloon passengers but only 16,871 steerage.

However, during these years, the Company did not fare as well as the Cunard Company in freedom from accidents. Indeed, they suffered many grievous disasters, but their courage never failed.

After several years of successful work, the SS City of Glasgow left Liverpool for New York on 1 March 1854 with 480 persons on board and was never heard of again.

The SS City of Philadelphia was wrecked near Cape Race, and the first SS City of New York on Daunt's Rock, near Queenstown, but without loss of life. Then, the SS City of Boston left Halifax with many Nova Scotians on board, disappearing forever, probably through striking ice or an iceberg.

The SS City of Brussels broke her main shaft in mid-ocean. Thousands were kept in painful suspense for weeks and afterward sank off Liverpool Sands after a collision with another ship. Subsequently, the SS City of Montreal was burnt at sea, but no lives were lost, and more than one of the other vessels broke their main shafts.

By 1872, the competition of the "White Star" line began to affect the Inman Company, as it did all other steamship lines, severely, and to meet it, they launched two magnificent ships with spar decks in 1873. Their engines were compound, with cylinders 76 and 120 inches in diameter and 5 feet stroke. Their speed on the trial trip was 16 knots.

These were the SS City of Chester., 444 x 44 x 34.6, 4770 tons, built by Caird & Co., of Greenock, and the SS City of Richmond, 440 x 43.5 x 34, 4780 tons, by Tod & McGregor. The latter ran from Sandy Hook to Fastnet Rock in 1873 in 7 days and 23 hours, and her first seven voyages to Queenstown averaged only 8 days, 11 hours, and 58 minutes.

But Mr. Inman was not yet satisfied. In 1875, Caird & Co. built the SS City of Berlin for the Company, the longest ship then afloat (except the SS Great Eastern) and, for a short time, the fastest.

Her length on deck is 520 feet, beam 44 1/2, depth to spar deck 34.9, 5526 tons gross, with compound engines; cylinders 72 and 120 inches in diameter with 51 feet stroke, 900 HP nominal, but indicating 4799, with accommodation for 202 first and 1500 second and third-class passengers.

She reduced the time to Queenstown to 7 days, 15 hours, 28 minutes, and 7 days, 18 hours, 2 minutes going west.

Then, to meet the competition of the SS Servia and other crack boats, they contracted with the Barrow Company to build a monster ship and called her the SS City of Rome. She was 8144 tons gross, 560 x 52 x 37, with six cylinders, three of 46 and three of 86 inches in diameter, and the engines indicated no less than 11,890 HP.

She made 18 - 23 knots on her trial trip and was magnificently fitted, but after several trips, she failed to reach the guaranteed speed due to a lack of boiler power, and the Company threw her up.

She passed into the hands of the Anchor Company. She was replaced by a boat building on the Clyde for the Dominion Line, the SS City of Chicago, 5202 tons, 430x45 x 33' 6, and 900 HP nominal.

This was the last boat Mr. Inman had built. He died soon afterward, deeply lamented, as did Mr. Dale, long the Company's New York agent.

Some American capitalists interested in one of the great railways were determined to take hold of the Company and buy a "controlling interest" in it. Although they could not put the ships under the United States flag, they took advantage of England's singular technical judicial decision to run them under the British flag.

British law does not permit an alien to own any interest in a British ship, but when in 1846, the collector of customs at Liverpool refused to register a new steamship, the SS Ecuador, for the Pacific Company because some of the shareholders were aliens.

The Company appealed to the Court of Queen's Bench, which decided that for registry purposes," an English incorporated company is a British subject, notwithstanding that some of its shareholders may be foreigners." This was rather humiliating to the great American nation, but they could not then compete successfully with British-built ships.

The new directors now decided to "eclipse everything afloat" with two ships to be built by J. & G. Thomson of Glasgow (Note 1). They must be admitted that they succeeded.

They boldly adopted "twin screws," and the ships inaugurated the sixth, last, and best "Epoch "in Atlantic steam navigation.

They were named the SS City of New York and the SS City of Paris. They are 527 feet long "between perpendiculars," 565 feet on deck," 63 feet beam," and 39 feet deep and weigh 10,4.99 tons gross.

They have two independent sets of triple expansion engines each, with cylinders 45, 71, and 113 inches in diameter and a 5 feet stroke; with forced draught, the engines of the SS City of New York indicate 18,400 HP, and on her trial trip, she made 20.13 knots.

However, for some reason, which even the builders cannot explain, the SS City of Paris's engines indicated 20,100 HP, and on her trial trip, she made 21,952 knots per hour, far more than the guaranteed speed.

Each ship has nine boilers, working at a pressure of 150 pounds to the square inch. The hulls are a stunning yacht-like model with handsome "cut-waters" and figureheads, certainly much more graceful than the straight stem now so much in vogue.

Each ship has 15 watertight compartments separated by strong transverse bulkheads. The two sets of engines are also separated by a longitudinal bulkhead, the significant advantages of which have been pointed out in a previous chapter.

These bulkheads rise up from the keelson to the saloon deck, or 18 feet above the load water line, and are said to have no openings of any kind. The buoyancy thus secured is so great that even if three of the compartments filled with water, the ship would not sink.

Practically, therefore, she may be considered as unsinkable. Massive steel brackets support the screws. The rudders are of an entirely new description, designed by Mr. J. R. Thomson and Professor J. H. Biles, and are controlled by new steering gear invented by Mr. A. B. Brown of Edinburgh.

Two hydraulic rams are used. The quartermaster on the bridge, which is said to secure greater steering accuracy than when the wheel is used, controls one on each side of the tiller and the pressure.

There are three funnels, but only light pole masts, without yards, which significantly reduce the resistance of headwinds and thus increase the speed of the ship. The ships are lighted throughout by electricity.

The dynamos have extra power, so they generate a current powerful enough to light up the whole ship and rotate the fans employed in ventilating her. Thus, 250,000 cubic feet can be drawn off from each compartment per hour. Each vessel can accommodate 540 first- and 200 second-class passengers, besides steerage, but carry little cargo.

In these days of luxury, the tendency is increasingly towards separating passengers and cargo: the former demanding a high rate of speed, and the latter large capacity with very economical engines and moderate speed.

There is so much for speed and safety, but these beautiful ships have other attractions.

Under the contract with the builders, they were not only to be constructed to prevent them from sinking under any circumstances that human foresight could provide against, but their accommodations for first-class passengers were stipulated to combine "the comforts of home with the richest luxuries of hotel life," and the contract has been carried out most faithfully.

Like the writer, those who have been in the habit of crossing the Atlantic twice a year for a quarter of a century will appreciate them entirely. Still, others may now be only anticipating their first sea trip.

In the early Cunard ships, the little "staterooms" so amusingly described by Dickens in his 'American Notes,' as "this utterly impracticable, thoroughly hopeless, and profoundly preposterous box, onboard the Britannia" were only six feet square; they contained two narrow bunks, like coffins, two washbasins, and jugs (the latter having a knack of pouring their contents over the lower bed), two little mirrors, two brass pegs, and a small seat, or "perch," as Dickens calls it.

There was practically no ventilation except on wonderful days when the stewards were allowed to open the "side ports."

The peregrinations of one's portmanteaus, the gyrations of one's hat, and the swinging of garments on the pegs were maddening, especially to those suffering from seasickness; no hot water or boots could be had, nor even your light extinguished, without bawling for "steward" perhaps a dozen times when the reply would be heard in the distance."

What number, sir? "(A wag on board the SS Canada once changed all the boots late at night, and the scene in the morning was indescribable.)

If you wanted a smoke, you had to go to a wretched little place over the boilers called the "fiddle," where the stokers were hoisting the ashes and where you often got soused with salt water.

There were a few books and prominent ones, but they were kept under lock and key, and a special application was necessary to get one. There was no piano, organ, or bathroom; the only promenade was on the top of the deckhouse, only 60 feet long, and at meals, you often had to climb over the backs of long benches to get to your seat.

The "Allan" boats had larger saloons and a better promenade. Still, the former was right aft, where the "racing" of the screw was often highly disagreeable and the motion of the ship excessive. There was only an apology for a "ladies' cabin."

Now mark the striking contrast in the "Inman and International Company's "ships, the new Company's name. The accommodation throughout is superb. The staterooms are large, lofty, and well-ventilated by fans and patent ventilators, which always admit fresh air but exclude the sea. Single and double beds can be closed daily, as in a Pullman car, converting your room into a cozy little sitting room.

Instead of the rattling, noisy water jugs, you turn a tap and get a supply of hot or cold water; you touch a button, and your steward instantly appears without a word being spoken.

Neat wardrobes enable you to banish your portmanteaus or trunks to the baggage room. You turn a switch, and you get an electric light. If you want a nap or wish to retire early, you can turn it off in a moment.

If you have plenty of spare cash and are willing to part with some of it, forty rooms on the promenade and saloon decks are arranged in fourteen suites.

Each suite comprises a bedroom with a brass bedstead, wardrobe, etc., a sitting room with a sofa, easy chair, and table, a private lavatory, and, in most cases, a private bath.

Here, you can entertain your friends or enjoy a game in privacy. You can also have the luxury of a morning bath and a promenade some 400 feet long.

To diminish seasickness, you dine in a saloon near the middle of the ship, beautifully decorated with fairies, dolphins, tritons, and mermaids, lofty and bright. The arched roof is of glass, 53 feet by 25 feet, and its height from the floor of the saloon to its crown is 20 feet.

Besides the long dining tables in the center, several small ones are placed in alcoves on both sides for families or friends' parties; revolving armchairs replace the benches, and electric lights illuminate the candlesticks with their lashings.

If you enjoy a cigar or a pipe, a luxurious 45-foot smoking room is provided; its walls and ceiling are paneled in black walnut, and its couches and chairs are covered with scarlet leather. There is also an elegant " drawing room," beautifully decorated and luxuriously furnished.

The "library" with its 900 volumes is lined with oak wainscoting, with the names of distinguished authors carved in scrolls. Its stained glass windows are inscribed with quotations from poems referring to the sea. The kitchen is isolated in a steel shell, the odors from which are carried off by ventilating shafts into the funnels.

The second cabin passengers are placed in the after-part of the ship, where they have a dining room, smoking room, piano, etc. The steerage passengers are also well provided for, having at least 300,000 cubic feet of space.

Provision is also made for divine service on the Sabbath day; at each end of the saloon, there is an oriel window built under the glass dome over the dining room. The casement of one of these serves as a pulpit. The opposite contains an organ, and many famous organists and vocalists have participated in the services and musical entertainments given on weekdays for charitable objects.

In truth, the ships were fitted with unmatched luxury and magnificence at the time, and they are said to have cost two million dollars each. The SS City of New York commenced running in 1888, and the SS City of Paris in the spring of 1889.

The Paris Exhibition of 1889 gave them a splendid business, and neither suffered from lack of attention from the United States press or the Telegraph Companies.

Due to a defective air pump, the SS City of New York was appointed at first as to speed. Still, ultimately, she made a record of 5 days, 19 hours, and 57 minutes from Sandy Hook to Queenstown (2814 knots), being the first to do it in under six days. From the beginning, the SS City of Paris proved herself to be a faster boat than her sister ship.

In August 1889, she made a record of 5 days, 19 hours, and 18 minutes (2788 knots) from Queenstown to Sandy Hook. She gradually reduced this until, in October 1892, she did it in 5 days, 14 hours, and 24 minutes (2782 knots).

This was not only the fastest passage ever made up to that time, but it continued until the SS Lucania was beaten in October 1893. The SS City of Paris made 530 knots on her best passage, and for a time was justly hailed as the "Queen of the Atlantic."

While it is unquestionably true that "twin screws "not only add to the safety of a ship but also give her immunity from serious detention when she meets with any ordinary accident.

Many experienced nautical men believe that the increased speed of steamships necessarily means increased risk, and the experience of these two good ships indeed tends to confirm this opinion, so far as their machinery is concerned.

The SS Persia's engines never made more than 17 revolutions per minute; those of the SS City of Paris make 89, and the latter's shaft is far longer and heavier.

There is, of course, force in the argument that there must be less risk in a 5 Days' passage than in one of 10 days; Captain Judkins, the first commodore of the Cunard Line, even argued that it was safer to go full speed in a fog than half speed because you are "sooner out of it," but few will now agree with him.

The strain, however, on such massive machinery that is now used has proved in several instances to be more than it can bear. Thus, the SS City of New York broke a crankpin going east, which disabled one of her engines, yet she made no less than 382 knots in less than 24 hours with the other, the most conclusive proof of the value of "twin screws."

The SS City of Paris has been still more unfortunate in this respect. On 25 March 1890, when going east with about 1000 passengers, she met with a most extraordinary accident, which may not happen again in a century. The immediate cause was the breaking of her starboard main shaft near the screw when making 80 revolutions per minute. This, of course, caused the engine to "race."

A connecting rod, 11 inches in diameter, broke, acting as a massive flail, smashing the two standards (weighing 14 tons each). The low-pressure cylinder (weighing 45 tons) broke off the condenser pipe and made a hole in the aft bulkhead, thus flooding the engine room.

All this would not have stopped her or imperiled her safety had not flying pieces of metal made three ragged holes in the longitudinal bulkhead, thus flooding both engine rooms and driving all the engineers on deck.

The forward bulkheads, protecting the boilers, remained intact and kept the ship afloat; she was towed to Queenstown by the Aldershot (s.s.). The condenser and injection pipes were plugged, and the water was pumped out when she proceeded to Liverpool with her port engine unassisted.

On docking her, the "lignum-vitae" bushing of the after bearing was worn away; the end of the shaft had dropped seven inches and been fractured.

There has always been a difficulty in lubricating the after-bearing of the shafts of screw steamships. To overcome it, the late John Penn of Greenwich invented the "lignum-vitae" bearing, which produced natural lubrication and is now in general use. It was this lignum-vitae which had worn away in such an extraordinary fashion.

The fact remains that the SS City of Paris escaped under the circumstances in which, according to the official report of the Board of Trade in London, "no ordinary vessel could have remained afloat after such an accident." The captain and officers were exonerated from all blame.

But the ship's troubles did not end here, for it was her lot to demonstrate later on the immense advantage of "twin screws" under different circumstances.

On 12 February 1894, when bound west, her rudder became disabled, and it was found necessary to put it back. With the aid of her two screws alone, she steamed a straight course back to Queenstown, 786 miles distant, in a little over three days!

A single screw might have drifted, helpless, for a month or until picked up and towed back by another steamship. The SS City of Paris returned to Liverpool, and while in the dock, a fire caused considerable damage to her second cabin.

The new Company has had other troubles to contend with. On 1 July 1892, the SS City of Chicago ran ashore in fog near Kinsale (Ireland) and became a total wreck, but no lives were lost.

The Board of Trade held an official inquiry, which resulted in the captain's certificate being suspended for nine months. In June 1894, the SS City of New York collided with the Delano near Nantucket. The former received no damage, but the latter was severely damaged, though she reached Balti more safely.

In the summer of 1894, a sensational statement of a passenger created some excitement in the newspapers and in the British House of Commons: the SS Majestic and SS Paris had been racing side by side, and the Paris had crossed the bows of the Majestic so close as to compel the latter to slow down.

It appeared, however, by the statement of both captains that there had been no racing and that the SS Majestic slowed to pass under the stern of the Paris—in a very proper manner.

Americans had become so proud of the performances of the SS City of Paris (although it was British-built) that Congress was asked to pass a special Act repealing the very stringent navigation laws in favor of her and her sister ship and admitting them to the United States registry.

This was done on condition that the Company (now styled "The International Navigation Company") should build an equal tonnage in United States yards of the highest type, costing about four million dollars.

As far back as 1865, the present writer had urged the repeal of these navigation laws upon Americans at the Detroit Convention for the benefit of American ship owners, as well as an act of justice to Great Britain and Canada, both of which have admitted the United States-built vessels to British Registry since 1849 upon a promise of Mr. Bancroft, the United States minister at London, that his Government would reciprocate.

The new Act would probably have been inoperative without a second Act, which authorized the Postmaster-General to subsidize large and fast steamships to carry United States mail.

In October 1892, a contract was entered into to carry the United States mail once a week from New York to Southampton for a subsidy of $4 per mile. As the distance is over 3050 knots, the subsidy will amount to about $750,000 a year, a much higher rate than the British Government ever paid.

The freight rates for goods having become entirely unremunerated, and the frequent detentions at Queenstown and the Mersey bar being a severe drawback, the Company now arranged to run to Southampton instead of Liverpool and cater primarily for first-class passenger traffic.

Southampton is within two hours of London and very near Havre; it also has splendid wet docks into which ships can enter and leave at any hour and where trains can run alongside the ship, a great convenience to passengers.

By February 1893, the Company's President, Clement A. Griscom, Esq., had obtained the British Government's consent to release the ships from their engagements to serve as armed cruisers. On the 22nd, the United States flag was hoisted in the SS City of New York with a grand ceremony, and both ships were re-christened, one as SS Paris and the other as SS New York. Under United States laws, the captains of United States ships must be native-born or naturalized Americans.

Captain Frederick Watkins of the SS Paris was consequently disqualified as a British subject. Still, to retain the command of his splendid ship, he renounced his allegiance to Queen Victoria. He became an American citizen, resuming his command in September 1894.

To carry out the contract with the United States Post Office, the Company immediately contracted with Messrs. Cramp of Philadelphia for two magnificent steel ships of 9,000 tons named SS St. Louis and SS St. Paul. The former was launched on 12 November 1894 in the presence of President Cleveland and a distinguished party.

With such a generous subsidy and the certainty of preference from American passengers, this great company has had a long era of prosperity. The Company has furnished the following description of the two new ships:—

- Designed by Professor Biles of the University of Glasgow.

- Consuming about 330 tons of coal per day, or 71 lbs. per I. H. P. per hour.

- The damage to the engine was frightful, and the repairs occupied thirteen months £7500 salvage was paid to the Aldershot.

Fry, Henry, “Chapter VIII: The Inman Line,” in The History of North Atlantic Steam Navigation with Some Account of Early Ships and Ship Owners, London: Sampson Low, Marston, and Company, Ltd. (1896): P. 112-131.

SS City of New York - 1888 - Ship's History and Information

THE "CITY OF NEW YORK."

This fine steamship left New York, August 22d, bound East, and arrived off Brow Head on the 28th, at 8.30 P. M., making the run in 6 days, 3 hours and 53 minutes. The fastest time is that made by the City of Paris, in 5 days and 23 hours; but the achievement is well worthy of record, and establishes the fact that the City of New York has a clean pair of heels. The time of her last westward trip was 6 days, 4 hours and 17 minutes, which beat her own westward record of 6 days, 14 hours and 20 minutes.

Source: Ocean: Magazine of Travel, Vol. III, No. 2, September 1889, Page 41

THROUGHOUT the leading hotels, railway stations and public resorts of England and Scotland have been distributed and hung. in conspicuous places, very handsome colored lithographs of the steamships City of New York and City of Paris of the Inman Line. There is no reason to doubt that such very attractive advertisements are influential.

Ocean: Magazine of Travel, Vol. III, No. 2, September 1889, Page 44

SS City of Paris (I) - 1888 - Ship's History and Information

THE "CITY OF PARIS."

This peerless greyhound heads the list for August 1889 with 5 days, 19 hours and 18 minutes to cross the Atlantic, Captain Watkins having made the run of 2,788 miles from Queenstown to New York, thereby creating a new record and beating her previous trip by 3 hours, and 49 minutes.

The daily runs as per log were as follows :

- August 23rd, 432 miles;

- August 24th, 493 miles;

- August 25th, 502 miles;

- August 26th, 506 miles;

- August 27th, 509 miles;

- August 28th, 346 miles;

- total, 2,788 miles.

Captain Watkins has great confidence in his steamship, and is of the opinion that she hasn't done her best yet. He fully expects to break the record before the present season will have terminated.

Source: Ocean: Magazine of Travel, Vol. III, No. 2, September 1889, Page 41

FIVE days nineteen hours and eighteen minutes was the last extraordinary run of the City of Paris, Inman Line, from Queenstown to this port, where she arrived in splendid shape August 28th. This beats her previous "best record" by three hours and forty-nine minutes.

Source: Ocean: Magazine of Travel, Vol. III, No. 2, September 1889, Page 42

Review and Summary of the Inman Line Archival Collection

Introduction to the Inman Line

Founded in 1850, the Inman Line Steamship Company revolutionized transatlantic travel, particularly for emigrants seeking new opportunities in America. It was among the first steamship companies to embrace iron-hulled, screw-propelled steamships, setting the stage for modern ocean liners. However, by 1885, financial difficulties and increased competition led to the company's liquidation, with its assets absorbed by the American Line and Red Star Line.

The Inman Line was instrumental in shaping North Atlantic travel and played a key role in the mass migration of Europeans to North America in the 19th century. The collection of passenger lists, ship records, and historical accounts in this archive provides a treasure trove of primary sources for genealogists, historians, educators, and maritime enthusiasts.

Key Highlights from the Collection

1. Passenger Lists – Tracing 19th-Century Transatlantic Journeys

Passenger lists from the 1870s-1890s offer an invaluable tool for genealogists and family historians, helping trace ancestors who traveled from Liverpool to New York and other major ports.

Notable Passenger Lists in the Collection:

- 21 April 1877 – SS City of Brussels (New York to Liverpool)

- 18 October 1881 – SS City of Chester (Liverpool to New York)

- 25 October 1883 – RMS City of Chicago (Liverpool to New York)

- 8 June 1884 – RMS City of Berlin (Liverpool to New York)

- 11 September 1889 – SS City of Berlin (Second Cabin, Liverpool to New York)

Why It’s Interesting:

- The large volume of steerage passengers highlights the significance of the Inman Line in transatlantic immigration.

- The Inman Line's extensive network provided a lifeline for European emigrants, many of whom passed through Ellis Island after 1892.

2. The Evolution of Ocean Travel – The Inman Line’s Innovations

The Inman Line played a crucial role in transitioning ocean liners from sailing ships to steam propulsion, making transatlantic travel more reliable and accessible.

Key Contributions:

- First major company to use iron-hulled steamships instead of wooden sailing vessels.

- Emphasized steerage-class accommodations, making emigrant travel safer and more affordable.

- Helped pioneer screw-propelled steamships, replacing the less-efficient paddle steamers.

Notable Ships in the Collection:

- SS City of Glasgow (1850) – The first Inman Line steamship, a groundbreaking iron-hulled vessel.

- SS City of Manchester (1851) – Set new standards for passenger comfort.

- RMS City of Berlin (1875) – The longest ship of its time and one of the fastest transatlantic liners.

- RMS City of Chester & City of Richmond (1873) – Designed to compete with the White Star Line, featuring luxurious accommodations.

- RMS City of New York & City of Paris (1888-1889) – Twin-screw vessels that revolutionized ocean travel, setting new speed records.

Why It’s Interesting:

- The Inman Line was a leader in ocean travel safety and efficiency, pushing technological advancements that influenced later liners.

- The City of Paris (1889) held the Blue Riband, breaking transatlantic speed records and ushering in a new era of fast ocean crossings.

3. The Rise and Fall of the Inman Line

Despite its early success, the Inman Line faced significant financial struggles, leading to its sale to American investors in 1886.

Key Events Leading to Its Decline:

Loss of Major Ships:

- City of Boston (1870) vanished without a trace.

- City of Brussels (1883) sank after a collision.

- City of Montreal (1887) was destroyed by fire.

Over-Expansion: Too many steamships in service led to financial instability.

Competition from White Star & Cunard: These companies offered faster, more luxurious crossings.

Change in U.S. Navigation Laws: The Inman Line was acquired by American investors but had to keep British registry to maintain its fleet.

Why It’s Interesting:

- The company’s challenges reflect the volatility of the steamship industry in the 19th century.

- It highlights the impact of ship disasters on business survival.

4. Inman Line’s Role in Immigration & U.S. Expansion

The Inman Line carried hundreds of thousands of European immigrants to America during the great waves of migration (1850-1890s).

Why This Matters for Genealogists & Historians:

- Passenger lists document family migration patterns, helping researchers trace ancestral journeys.

- Many immigrants landed at Castle Garden (before 1892) and later Ellis Island, making these records vital for understanding immigration history.

- The company’s focus on affordable steerage class tickets made the American dream possible for millions of European families.

Who Would Benefit from This Collection?

For Genealogists & Family Historians:

- Passenger lists provide essential records for those tracing ancestors who immigrated from Ireland, England, Scotland, and Germany to the U.S.

- Helps uncover family migration stories through ship manifests and route details.

For Maritime Historians & Ocean Travel Enthusiasts:

- A comprehensive look at 19th-century ocean travel, including ship innovations and passenger experiences.

- Chronicles technological advancements in steamships, from early iron-hulled vessels to record-breaking express liners.

For Teachers & Students Studying Immigration History:

- Primary sources like passenger lists, ship histories, and disaster accounts bring 19th-century transatlantic migration to life.

- Helps contextualize Ellis Island immigration, industrial expansion, and the role of steamship companies in global migration trends.

Final Thoughts

The Inman Line Archival Collection is a rich resource for anyone interested in 19th-century maritime history, immigration, and ocean travel.

As one of the earliest transatlantic steamship companies, the Inman Line shaped how people crossed the Atlantic, pioneering iron-hulled ships, screw propulsion, and mass steerage-class travel.

With detailed passenger lists, ship histories, and records of triumphs and disasters, this collection provides an unparalleled window into the golden age of steamship travel and the experiences of those who journeyed across the Atlantic in search of a new life.