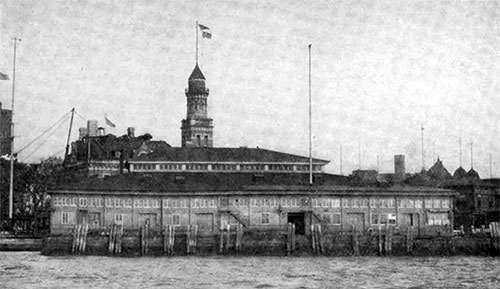

The Arrival of the Immigrant at the Barge Office – 1898

The Barge Office. The Immigrant's First View of The Metropolis Of New York. Metropolitan Magazine, February 1899. GGA Image ID # 14c0e4f3dc

Its "steamship day" at the Barge Office, that turreted building of gray stone On the Battery's outer wall. Up the bay a few hours before an ocean liner has been crawling in from some of the cities of far-distant Europe.

The onlooker might have seen, if he had been aboard that boat, a strange sight or two-the people of the steerage as they felt they were at their journey's end and herded eagerly in their limited deck space to get one glimpse of what America was like.

These are the men and women, the children in arms and clinging to skirts, that the Barge Office receives; the motley, ill-assorted crowd the Federal officers of Immigration sift and winnow with a skill you wonder at.

They have been brought, baggage, babies and all-many babies and little baggage, alas!-to these sheds of the Barge Office now taking the place of burned Ellis Island, in a broad-decked Government harbor boat, a mass of hundreds of the unwashed tugging at grimy bundles. A few cheap trunks proclaim the existence of "steerage aristocrats."

But there are few of these. The bulk and majority have little more than the clothes on their backs, hardly anything in their pockets. Yet, for this, they care not at all.

The discomforts of the voyage, too, are forgotten. Are they not on the threshold of their hopes, and have they not already caught one sight of the land of gold-America they heard discussed so eagerly over their countryside, in their village lanes, or their cities' alleyways?

So. landed from the boat that has taken them off their ship, divided into groups that will, individual by individual, be passed through America's prominent immigration mill, the newcomers stand or crouch patiently, hundreds at a time.

Hungarian Peasants Passing Through the Barge Office. Metropolitan Magazine, February 1899. GGA Image ID # 14c0244f77

The first lesson they have to learn is that of waiting, and this the people who are the offscourings of Europe learn readily. Instead, it is the one thing they already know.

A year at the Barge Office sees men and women of all nationalities, of course, families from the remotest and smallest States of Europe, from localities even whose names are strange to the best-educated American.

But there is always one tide that overshadows the rest, one nation or race that is having its day and pours into New York from abroad in a stream that makes the other comings of little consequence.

Thus, years ago, came over significant sections of Ireland and Germany; thus, at times have descended upon America the latter-day Norsemen; therefore in the eighteen-eighties, the flux from the Ghettoes, the Juden-strasses and the village streets of Russia, Russian Poland, and all of Jewish Western Europe.

These tides have now approximately ceased. In their places come in droves, as fast as the steamers can carry them, men and women of Sunny Italy.

It is not that there are no longer immigrants from the other countries, but that Italy has of late years leaped into the first-place ln the immigration problem.

Flowing thinly now is the stream of Hebrew immigrants, scant is the number of Germans and Austrians who want America for a new fatherland. Italians are the immigrant of the hour.

The boot that is Humbert's domain seems to be leaking, and if you, oh! man, who reads and studies, should stand in the Barge Office day after day for a while you would think that every Italian town and village, yes, and every hillside, was being deserted in the race for the dollars of America.

Set down in figures this migration of the "Dago," as we have come to call him, and, which does not seem an inappropriate term as the raw product is seen at the Battery before he has "squeezed through," is really extraordinarily large.

The figures that follow were compiled from the Immigration records for a speech made in Congress by Charles W. Fairbanks of Indiana, last January.

For the seventy-two years ended 1892, out of nearly 15,000,000 of immigrants there were 4,700,000 Germans, 3,600,000 from Ireland, 2,500,000 English, 1,030,000 Norsemen and Swedes, and but 517,000 from Russia and Poland, 585,000 from Austria-Hungary, only 526,1100 Italians.

In the year 1803, out of 429,000 immigrants, 72,000, or one-sixth, were Italians. Italy, never of account before, stood second on the list behind Germany only, and but 6,000 souls in the rear.

During the years that have followed, the percentage of people from "the boot " has enormously increased. In 1804, 43,000 Italians came over, again one-sixth the total number of steerage arrivals, Italy again became the second-highest country for immigrants.

In 1895, she passed Germany and was led only by Ireland, this being, for some reason, a massive year for people from the "ould sod." In the last two years, Italy has held undisputed leadership, with 68,000 men and women in 1896, and 60,000 in 1897, the first year more than one-fifth, the latter year fully one-quarter.

These figures concern the entire immigration into the United States, and this only serves to strengthen the point of the outpouring of modern Italy upon us. For the country, however, read New York City.

It means much the same thing. But a small, insignificant, inconsiderable fraction of the immigrants' land at other ports. New York is what the town laborer, the farmhand, always has in his mind.

He may wander elsewhere after a short stay, he may even simply pass through the city, but "Newa Yorka" is his goal and the one geographical title besides "Amerlc" that rings over United Italy today,

Some further curious statistics are to be found. It has been learned that the destination of 75 percent of the immigrants arriving here in 1807 was the North Atlantic States, 40 percent, New York State alone. Illinois, including Chicago, (to which city it would be thought huge numbers would go) is credited with, but 5 percent and to Pennsylvania there went but 14 percent.

Take the Italians (nationalities are not separated In these figures) from the reports of expert observers among the Federal officials, and it will be discovered that an even higher percentage remain in and about New York, for some weeks after their arrival at least.

Like the traditional "woman's work," the labor of the Federal officers at the Barge Office is never done. An ocean steamship lands six hundred, a thousand souls, upon them at one instant.

Half a dozen such steamers may heap up human freight at their door for "examination" in one single day. The arrival of two or three ships, large and small, is not an infrequent occurrence. Now, all these entitles, these shreds and patches from foreign shores, must be handled.

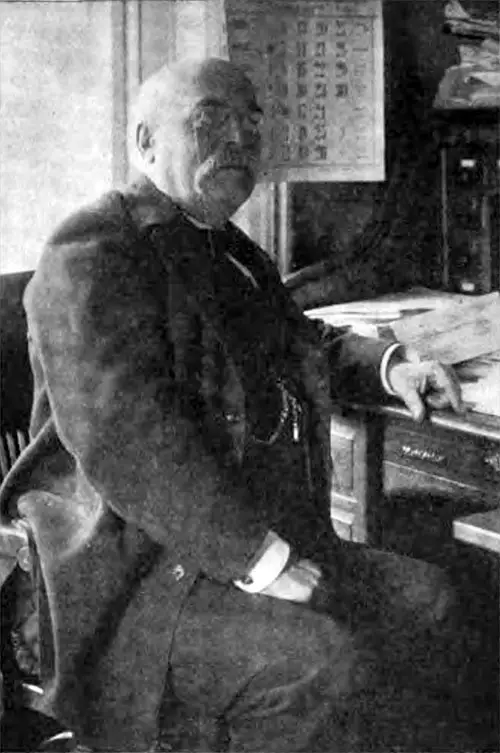

Hon. Thomas J. Fitchie, United States Commissioner of Immigration, Port Of New York. Metropolitan Magazine, February 1899. GGA Image ID # 14c00a6d74

You and I, standing ln the Barge Office surveying the scene with Thomas Fitchie, New York Commissioner of Immigration, or Edward F. McSweeney, Assistant Commissioner, an expert of much repute in the management of foreigners, see only the mass, we number these people that have crossed the sea merely by hundreds.

Hon. Edward F. McSweeney, Deputy Commissioner. Metropolitan Magazine, February 1899. GGA Image ID # 14c019b239

In the mass, they delight our sense of the picturesque, they disgust our sense of smell. Yet, they gathered there in long lines. A cargo full of human life, in costumes that breathe forth the villages and cities of foreign lands, quaint in their bits of talk, with babies bright-eyed and children dirty but yet adorable, Italy comes to America has its charm -- and a strong one.

But all of this is in the mass. It is the part of the officials to examine each thread of this gay-tinted fabric. Each man and each woman-yes, and each child, too-must pass in turn in review before the stern eyes, the searching questions of an Inspector.

With the consummate skill that official probes into each life. In the vast crowd, he sees only individuals. The quaint picture is nothing to him; there is only the man, or perhaps the woman, before his desk.

Thus, in the great room of the great shed where the immigrants await the test that decides upon their admission to the "land of gold," there come to be, after a while, no longer a confused congregation of human figures.

But men and women just like you and me, with their hopes and ambitions, their loves and "vain regrets," their little families and their future's - all this, indeed, in a minor sense, for the bulk of these people are of small intelligence, but yet none of these things are lacking. The Government, in its review, tries only to set apart the sheep from the goats.

The Board of Inquiry. The Men Who Pass Upon the Eligibility of Immigrants to Become Americans. Metropolitan Magazine, February 1899. GGA Image ID # 14c0091008

Italy is lined up in these "pens" under this shed's roof, the "pens" being for the newly arrived aisles made by stout iron railings; for the detained, those that have been examined and not admitted, the "rejected." and those who are to go before the Inquiry Board, spaces blocked off into rooms by durable iron netting from floor to ceiling.

But one shipload is handled a time, and each immigrant has a card, distinguished by a letter and a number. The number is his identification on the ship's manifest, the letter shows the aisle in which he is to stand while waiting.

Briefly, the inspection is a simple one. With health and a little money, a man, no matter how great his family, is considered a desirable Immigrant. The doors of the promised land fly open at a touch.

Vigor and cash capital of about $30 will carry the foreigner and his household through the lines without trouble. The energy is evident lo the doctors who scan each man, two or three watching the line in review, one for certain sorts of physical defects another for conditions of health of another order.

Thus a man is sometimes ordered abruptly out of the line. "Another!" Both doctors were right. This immigrant had an infection of the eyes, (the doctor noticed it by the way he walked,) this man phthisis, (the medical eye suspected it.)

As to finance, the wanderer from abroad must hand up his little hoard to the Inspector for counting. With the best of the Italians who come here, this consists of a few pitiful greasy bits of paper money, a coin or two, too few to even jingle.

A day spent watching these lines of peasants and Mediterranean city poor wears quickly along. It is really the offscourings of King Humbert's domain that is passing before your eyes.

No skilled working people these, few even that, though in this country of opportunities, will ever rise above their present planes. Nearly all are of the fashion that is content to stay poor, that cares but for labor and the lowest places.

A large percentage of them have no intention of remaining more than a few years. Five hundred dollars, a thousand at most, laid aside, and then Italy again, and a life of idleness beneath the vines of some tiny house in a village. Five hundred dollars is a fortune to an Italian peasant.

Meanwhile, during their days here, they keep sending their earnings abroad. The authorities here figured that the incredible amount of $25,000,000 to $30,000,000 is sent to Italy each year by the Italians in New York alone.

And yet, seen here, on the threshold of America, these men and women of Italy are strangely fascinating. Under all their poverty, all their uncouthness, under their illiteracy, they bring with them the aroma of the hills and old towns of South Europe, the romantic charm of the people of the Mediterranean shores. They are mainly from the regions around Naples and Genoa, some from Sicily, others from Calabria.

Nearly all were farm laborers, for it ls the country regions that are now sending their hordes over in ships; it is the genuine peasant that is coming.

Here the men will work as common laborers, mainly in stone quarries and on excavations. The boys will do odd jobs, such as carrying water in factories. The women will find employment as cigar makers or tailor shops, and the girls, even down to the very smallest, will do housework. Such is the future of these Italians who stand watching and waiting at the bar of America for permission to enter.

There is standing before the Inspector Angiolina Felicetta with $12.15 in her little purse. She has come to join her husband, who, it is afterward found, is waiting for her in the crowd outside.

He has come ahead to test America. AH is seemingly propitious; the young wife - a girl, has come over to join him. She is still seventeen, a slip of a Neapolitan. A clumsy-fitting dress of green and yellow stripes sets badly on her girlish figure.

The white cotton lace on it is torn and soiled. She wears carpet slippers, and on her head, a gay fazzoletta di testa (handkerchief) is coquettishly entwined. Angiolina, according to American canons, is dirty. In Italy, you would pitcher her at once, and fresh off the steamship, she has not lost her Old-World charm.

For with the green and yellow stripes, there is a gorgeous pink ribbon about her neck and in her hand a yellow and green basket—her entire wardrobe.

Francesco—his last name does not come to mind—a strapping young fellow, so capable-looking that he was passed with but $6 in his pocket, was a costume study in himself.

He wore a pink shirt, a blue necktie, a dark-blue suit, and carried a gray shawl. And he was but a suitable type of the men along the line. Gayness in costume invariably marked them.

With the women, in their peasant garb, gayness never fails. What with the brightness of their gowns, their strange slippers, the fazzoletta di testa, the scala, or the neckerchief, the picture in review is never-ending, is panoramic in its features.

The Bambini, the babies, swathed in long bands (fascia) are an integral part of the scene. With the aid of an Inspectress, the pretty young Italian girl mother being influenced, the writer unrolled one of these babies from its numerous wrappings.

Long stripes of some Italian fabric, yards of it, were wound about the child. Neck to feet, it was covered. Four separate wrappings in all bound about this baby. When rolled up, its toilet complete; it was one stiff mass; a board could be no more rigid.

A hot Summer's day, the Inspectors were mopping the sweat from their brows. And the baby, a modern mummy, lay on its mother's knee and smiled.

Outside in the park and in a special room, the Italians of New York are continually awaiting their friends. Express wagons stand for the bundles, bags, and the immigrants themselves.

At the meetings, there is much joy. This is for the immigrants admitted. In the meantime, in the "pens" the "detained" wait, eat, and sleep. It is an unusual sight to see the mealing, especially of the children. The steamship companies pay for that.

Cromwell Childe, "The Arrival of the Immigrant," in The New York Times, 14 August 1898, pp. 30-31.