A Mother’s Story of Ellis Island: An Emotional Account of Immigration and Family Separation (1911)

📌 Explore a poignant narrative of two mothers and their children at Ellis Island, highlighting the emotional challenges and hopeful reunions faced by immigrants in the early 20th century.

A Mother's Story of Ellis Island (1911)

Relevance to Immigration Studies

“A Mother’s Story of Ellis Island” (1911) is an insightful narrative that powerfully portrays the emotional and physical challenges immigrants faced when arriving at Ellis Island in the early 20th century.

For teachers, students, genealogists, and historians, the article offers an empathetic view of the immigrant experience, particularly the hardships and hope surrounding family separation, quarantine, and the immigrant journey. It provides a poignant lens into the intersection of personal tragedy and cultural exchange, making it an essential read for those studying immigration, social history, or the human aspects of migration.

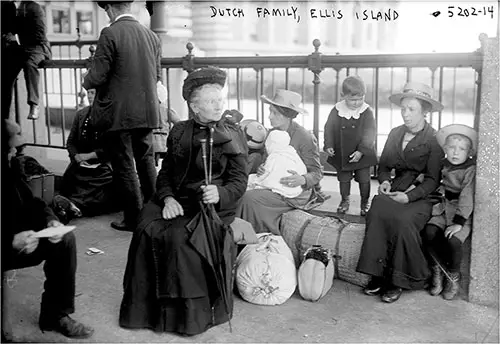

Dutch Family at Ellis Island circa 1915. George Grantham Bain Collection. Library of Congress # 2014710706. | GGA Image ID # 148c69db77

They were sisters in widowhood and motherhood, their resilience shining through despite the stark contrast in their circumstances.

The one was tall and full-throated as Juno, with coal-black hair and the languishing eyes of the southern Italian. Her hair waved from her forehead and warm, white neck in soft undulations, concealing the little gold rings in her ears. The scarlet kerchief that followed the oval of her face touched the purple peasant's gown that clothed her young figure.

With scarlet cheeks, vivid lips, and a rounded outline, she looked the embodiment of the sunshine that had shone on her since babyhood. She spoke with easy gestures of her expressive hands, with her head on one side and her eyes speaking faster than her tongue. An ancient cross of intricate artistry lay on her breast, and her eyes glowed when they fell upon it.

The other woman was small and angular. Her straight black hair was drawn severely back from a pale and haggard face with the aquiline profile of the Ghetto—a nervous face wearing the flat look of utter exhaustion. Maria's expansive nature smiled on all alike as sunshine sought out every little twig, her soft eyes catching sparks from other eyes as the Sorrento sky smiled back at itself in flowers.

Rachel sat still on the edge of her bed, her head hung low. It was the steerage. She sat with her face turned away from all the other immigrants, avoiding glances as if they were blows. She shivered as if the cold from the dreary steppes of Russia blew on her. She was as nervous as the Ghetto when the czar's emissaries were abroad.

These two women spoke a different language and knew a different world. However, they were both exiles fast-speeding toward the land of liberty—the one all sunshine, despite her widowhood; the other all shadow, yet with the beacon light of an only son.

Maria Bianchini gasped and clasped her large and shapely hand over the iron rod of her bed. As the long rows of gray beds rose to meet her eye with the ship's motion, a small boy swung down the aisle. This was normal. But back of him came his shadow—his shadow in the flesh.

Maria's white teeth flashed, and she watched them come, navigating down the rolling floor. The other woman gave no sign, though her sharp black eyes were swimming with light, passionately keen to the existence of her chiefest treasure.

Maria's son approached her, putting a grimy, small brown hand into her eager clasp. His shadow swayed to Rachel Kohn and put a grimy, small brown hand into her thin, nervous one. Maria's rippling voice broke into little cries of delight. She bent and kissed her child on the eyes, forehead, and warm, moist lips. She surveyed him at arm's length and said many nothings to him. All the while, she gazed from one boy to the other.

The Jewish mother turned tense eyes on her son as if they would draw his very soul to hers, but she said nothing.

For an instant, the eyes of the two mothers met in wonder. The boys might have been brothers—they were as like two peas: the same mischievous eyes of night flashing out from curling lashes; the same ivory skin and jet-black curls lying like a cloud close to the warm white brows; the same impulsive, ardent faces; the same shrug of a shoulder and dramatic gestures of small brown hands.

The son of the southern Italian and the son of the Jew both showed Oriental touches of color and contour, with the characteristic curve of the brow and nostril, the high cheekbones, the curl of the hair, and the passionate fire of the eyes.

Maria dapped her hands and laughed—the resemblance between the two children was manifestly a miracle. She turned a radiant face to Rachel with many exclamations of astonishment. But Rachel, drawn into herself with much brooding, held aloof. Her eyes dropped away from Maria's smiling eyes. However, she had a swift hand and lifted Giuseppe's face with her small, supple fingers until the boy jerked away with a blush.

During the long hours of storm and sickness, or the merry ones when the steerage, gay in spirit and plumage as tropical birds, smiled back at the smiling skies from the open deck, the boys played together, their bond growing stronger with each passing moment.

They often ate their supper under the early stars; they played games, taking Maria into their counsel, and she was ever ready to be one of them. But Rachel sat in the shadowland, hugging her grief in dumb passion, with her eye following the wistful devotion of her son to Maria.

For he listened to her merry songs, followed her busy fingers as she cut out paper soldiers and war-boats or fashioned pigs out of potatoes, and because he was curious and venturesome, being a boy, he even made free to touch the cross with his finger, his eyes full of wonder. After that, Maria smiled and gave him a blue-mantled plaster Madonna and a little string of blue beads, at which Rachel frowned, though he pulled them apart for marbles.

Once, he stood with wide eyes, watching Maria's lavish, warm, moist kisses on Giuseppe's mother. Maria's kisses were rare and light as flakes of snow. Rachel resented Maria's smiles, friendly overtures, universal motherhood, and the cross on her breast.

A fortnight, it brought the new land. It rose one morning before their sea-weary eyes like a structure of fairyland woven overnight—the vast range of New York dipping its feet in the bay, the snow-capped peak of the Singer Tower, blue with the early morning haze, rising above the lesser skyscrapers; the deep canons of streets, and the plumed feathers from myriad chimneys; with Lucifer, Star of Morning, hung low, like Destiny, for eager hands. The mothers, filled with hope and excitement, eagerly awaited the new chapter in their lives.

Maria wondered what Giuseppe would do now that the boys were soon to be parted, but she need not have taken the trouble. The physicians at quarantine came aboard. Giuseppe had a little fever. There was a slight eruption over his body, and Isidore, his very likeness, was also not unlike Giuseppe.

Then came the parting from the mothers. The boys were sent to Hoffman's Island to quarantine with the measles. The mothers, as is the Government's custom, were detained at Ellis Island to await the recovery of their sons.

Maria cried and held her arms to Rachel, seeking comfort in their common woe. Rachel gave no sign that she was staying close to Maria, which was a response. She stared into space, more like a dead woman than a living one, save that at times, her body trembled, shaking hysterically. She shrank from Maria and her sympathy.

And Maria soon fell to quiet words; she touched Rachel's pallid cheek with the tips of her rosy fingers, saying in her melodious tongue—of which Rachel knew nothing save the broad vowel of gentleness—that their sons would soon be back—why should they not smile? The boys were not divided—what games there would be! And every day, there was the report from quarantine!

The two boys in the children's hospital on the island occupied adjoining cots. The measles were light, and they never tired of playing with each other. Sometimes, Giuseppe, when the white-robed nurse was not looking, climbed up into Isidore's cot, and sometimes, Isidore would return the visit. The nurse could never tell them apart, nor could the doctors, save for the little identification tag of cardboard bearing the name tied on each slender wrist.

Without rustling of garments or battling of wings, Fate entered the hospital ward in the innocent form of marble, a small, white, shining marble in the hands of Giuseppe. Isidore's black eyes flashed as Giuseppe held it up, and he put out a swift hand for it. But Giuseppe did not like to part with it, so Isidore pounced down into his neighbor's little cot.

Giuseppe sprang to the floor, Isidore following him. There was a tussle. They tore at each other's hands. Over and over, the two white-gowned little figures tumbled. There was a cry—the marble had rolled along the floor to the register.

The nurse flew down the aisle at the cry, and the two small boys tumbled wildly into bed. Two pairs of bright, audacious eyes softly closed; the fighting little fists, with adorable abandonment, lay suspiciously still. The tags from their wrists were in little bits on the floor.

Their pretense at sleep made the nurse laugh as she devoted herself to making new tags and hurriedly tied one to each wrist. The doctors were making their rounds; a little girl was shrieking in German for a glass of water, while a small urchin with a placid face and unwinking eyes was politely admonishing her in Basque—which was not understood by anyone—to be still. So it was no wonder that Giuseppe was tagged, Isidore and Isidore Giuseppe!

That night—a bleak night of cold, driving rain—something went wrong with the steam pipes, and for several hours, the best efforts of workmen and officials were unavailing in restoring the hospital to normal temperature.

A damp chill crept through the ward, and, despite extra covers, the following day, from more than one tiny cot came the sounds of labored breathing and the short, quick hack of suppressed coughing—pneumonia was demanding a toll.

Three days later, as the clerk of the records was making out his daily death report, he found the name of Isidore Kohn among the little pile of wrist tags that were no longer needed.

The mother at Ellis Island was notified. She sat still, and her mind was blank—until she heard Maria's voice. Maria had her boy, and she—Rachel—was bereft! She could not look up into Maria's face.

Yet Maria was bending over her. Maria's tender face was close to her, and her great, warm white hands took the cold, thin hands on her own and strove to warm them; Maria's tears were flowing for her.

The news of Rachel's trouble was already in the detention room. As she lifted her wan face, she read it in the silent eyes of foreign women. She was a stranger in a strange land—the Government would bury the boy—it was the custom.

All that day, Maria watched over her with immense pity. She often timidly stroked her hair, longing to enfold the stricken, defiant little soul in her mothering arms, but Rachel, rebellious against fate, rebellious against the sight of this mother of a living son, opposed a cold steel shield of resentment to Maria, and would not be comforted. She wished to return to her native land, to seek again familiar faces; the new land had been for the boy, but there was no need—now.

As the Barbarossa steamed slowly down the bay in the noon sunshine's dazzling white, a lonely black figure hung over the rail on the steerage deck.

The sea-line of New York glittered into a softer outline with distance and the haze, but the listless eyes of the woman did not watch it. Maria, in the detention room at Ellis Island, waiting for her boy to come to her, yet with sorrow for the other mother clutching at her heart, had parted from the dry-eyed woman with ineffable pity. But Rachel had yet to give a response.

Under her unseeing eyes, the city quickly shifted into kaleidoscopic scenes, and the merry voices of little children from a Government barge, rocked by the wash of the liner, reached her. They were gay—heart, costume, and eye—coming from the quarantine station to join their parents at Ellis Island.

It seemed outrageous to her that the little voices could be happy when a loved voice could no longer reach her listening cars. Yet, as a traveler may peer over an abyss in sheer fascination, she daringly leaned over the rail.

Her heart stopped—it ceased beating for a long moment. Then she pressed her fingers against her side to still the great throbs that suddenly beat there.

Her wide, motionless eyes, like those of a mother bird who sees her little one restored to the plundered nest, looked into the sweet, wild eyes of her son. She knew the truth. With a tremulous cry, she flung her arms around a seaman, shrieking to him in Yiddish to stop the ship, that her boy—her darling boy—was there alive! Alive!

He gaped at the woman with an open mouth uncomprehendingly—she was mad indeed! He pushed her away, and she fell on her knees yet boldly scolded him for his slowness and stupidity. The west wind kissed her hard cheek and blew the hair about her face. He frowned and called out to a deckhand to take her away.

She saw them coming toward her. The ship was steaming up, and childish faces crowded over the barge rail to gaze at the departing steamer; she saw all but one small face, with mischievous dark eyes. With a sob of joy, she was over the ship's rail and struggling in the green, dancing waves.

As the cry went up, "A mad woman overboard!" and the ship slowed down while a boat was put out, a seaman from the barge was grappling with the woman, and rescued and rescuer were soon aboard the barge.

Rachel, faint and exhausted, gasped at the chill that crept over her. With her overjoyed arms around her son, she opened her eyes. There were sudden smiles curving the lips of all classes on the big ship steaming outward, clearing of throats, and abstracted smiles of callous deckhands on the barge nearing the city.

The old doctor, his hand on her pulse, a mist in his eyes, knelt like a priest before a naked altar, yet he chuckled in a very human way over her as he watched her watch her son.

Suddenly, he caught his breath, for her face had gone white. She rose and knelt on the bare deck, the tears flowing down her pale cheeks. She flung her soul into half-remembered prayers.

The turning point of Rachel's life lay in that moment—she forgot herself. Everyone looked on in wonder. Even the children ceased their chattering and smiled faintly.

"Joy's been too much for her. Joy has been too much—" The old doctor shook his head.

But it was Maria she was thinking of, praying for—Maria, who would be down to meet the barge; Maria, who waited for her little son with the sunshine in her eyes.

The barge, a floating house of laughing children, slowed up and backed into Ellis Island's breakwater, sliding in close to the island's heart and the hearts of the waiting parents. There was Maria, Maria with her beautiful smile, standing serenely in the sunshine.

Rachel, a woman of gloom, timidly wrapped one arm around her son, daring not to press him to her as she thought of the other mother, and slowly went down the gangplank. She threaded her way through the immigrants; her color had risen, and her voice faltered when she began to speak.

Maria stared at Rachel—stared at Isidore. Then, a new light leaped in her eyes. Rachel's boy was not dead! Maria flung back her head and laughed—then the laugh caught in her throat. She took a blind step nearer—Rachel slowly walked to her, leading the boy, who hung back out of pure perversity of boyhood.

But suddenly, the smile around Maria's mouth, the frantic demand of her eyes, or perhaps some subtle vision that belonged to childhood made Isidore throw himself impetuously into her arms. And Rachel, with a wealth of sudden love like a stream whose dam is broken, flung her arms around the two as they embraced.

"Ours together—ours together!" she was crying in Yiddish.

Maria did not understand the strange words but felt their meaning and all the truth flowed in upon her. As her great heart broke in anguish and her tears mingled with Rachel's, she leaned back against the strength of the thin, supple arms; she sought the sanctuary of Rachel's sympathy.

And Isidore, all boy—mischief, and audacity—suddenly flung an arm around each woman and essayed his first English word—"Mother!"—truly one mother. His look was for them both, like the new language that would be theirs together, and the particular worship and wonder of his eye made Maria suddenly catch him to her with a pang of love.

The two women went out into the new land with their burdens, but side by side, and seldom letting out of eyeshot a venturing, wayward boy, who trudged on a little ahead, alive with the immortal hunger of youth.

Neumann, E. Howell, "The Mother," in Everybody's Magazine, Volume XXV, No. 6, December 1911

Key Highlights and Engaging Content

The article's central narrative—focused on two mothers from different cultural backgrounds, Maria Bianchini (Italian) and Rachel Kohn (Jewish)—is both engaging and emotionally charged. The vivid descriptions of their emotional connection, despite their starkly different personalities and backgrounds, create an enduring picture of shared humanity.

One of the most striking images is of “Dutch Family at Ellis Island circa 1915”, which captures the hopeful faces of a Dutch family disembarking, symbolizing the anticipation and uncertainty faced by many immigrants.

The children’s bond, despite the cultural and language barriers, serves as a metaphor for the future of immigrant integration into American society. The playful, innocent friendship between the two boys, Giuseppe and Isidore, contrasts with the mothers’ burdens and highlights the potential for cross-cultural understanding and the eventual merging of diverse communities.

The photo of “Dutch Family at Ellis Island” reinforces this theme, offering a visual connection to the central narrative of hope and adaptation.

Equally impactful is the emotional tension between the mothers as their sons are separated due to quarantine. The story of Rachel’s initial despair and the subsequent joy of reunion is a testament to the perseverance and love that mothers experience in times of hardship.

The striking image of the “Betrayed Polish Girl Who Came to Find Her Lover, Is Detained at Ellis Island Pending the Outcome of the Inquiry” highlights the uncertainty and complex nature of immigration during this period, providing a visual counterpoint to the personal stories in the narrative.

Educational and Historical Insights

For educators and historians, the story is a valuable resource for exploring the immigrant experience through personal narratives. It provides an avenue for discussing the social, cultural, and emotional dimensions of immigration, which are often lost in purely statistical or political accounts.

The details of the quarantines, the medical inspections, and the emotional separation of families bring to life the bureaucratic challenges immigrants faced upon arrival.

The story also offers insight into the diverse backgrounds of immigrants arriving in the early 20th century, including Italians, Jews, and other European populations, while also touching on their relationships with one another. The shared moments of joy and grief reveal the complex, often unnoticed human connections that formed in immigrant communities.

Educators could use this narrative to help students understand the immigrant experience beyond just facts and figures, emphasizing the emotional and cultural exchange that defined the immigrant journey.

Final Thoughts

A Mother’s Story of Ellis Island is an emotional and richly detailed narrative that resonates deeply with themes of hope, hardship, and the immigrant experience in America. It captures the universal desire for a better life, the struggle for belonging, and the power of maternal love in the face of adversity.

The story is not just about the two mothers but about the broader experience of millions of immigrants who passed through Ellis Island, each carrying their own stories of sacrifice, hope, and perseverance.

This article is a crucial read for anyone interested in the immigrant experience, the early 20th-century migration process, or the social history of America.

It beautifully portrays the emotional side of immigration—often left out of formal historical accounts—and provides valuable material for further exploration of the immigrant narrative in American history.

🔎 Research & Essay Writing Using GG Archives

📢 This is NOT a blog! Instead, students and researchers are encouraged to use the GG Archives materials for academic and historical research.

🔎 Looking for primary sources on Titanic’s lifeboat disaster? GG Archives provides one of the most comprehensive visual collections available today.