Homeless Immigrants Christmas at the Barge Office: A Moment of Cheer Amidst Hardship (1898)

📌 Explore the heartfelt experiences of immigrants spending Christmas at New York's Barge Office in 1898. Learn about the role of charity, festive meals, and the impact of immigration policies during the holiday season.

Homeless Immigrants Christmas at the Barge Office - 1898

Overview and Relevance to Immigration History 🗽🎄

"Homeless Immigrants Christmas at the Barge Office" from December 1898 provides a heartwarming yet sobering look at the immigrant experience during Christmas at the Barge Office, New York's entry point for immigrants during the late 19th century. This piece is valuable for teachers, students, genealogists, and historians as it offers insight into both the human and systematic aspects of immigration processing at the time. The article reflects on how America, despite its struggles and harsh immigration processes, welcomed newcomers during the festive season with a small semblance of warmth and community. It underscores the challenges faced by immigrants and the institutional support that helped alleviate their plight, especially during the holidays.

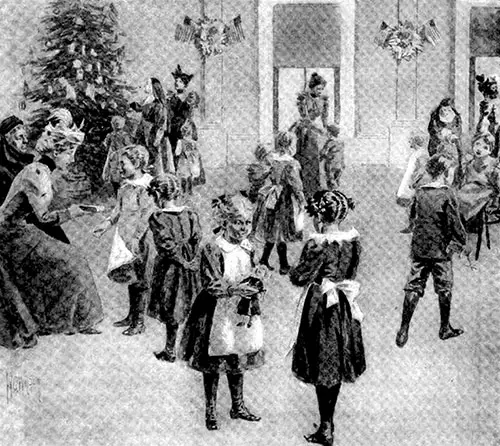

"And the Christmas of the Immigrants at the Barge Office Is Not a Bad One, After All." Drawn by W. O. Wilson. The Puritan, December 1898. | GGA Image ID # 14f4df5842

Sometimes, crossing the wintry sea, they lose track of days. In the steerage, one does not find silver-mounted calendars. The tossing of the ship, the dread of the unknown land, the misery of seasickness, the heartache of homesickness—these drive dates from the mind.

And so, when a particular midwinter trip is over, and the crowd of dazed immigrants pours into the dreary office, a cry of surprise is often heard, and an excited chorus in which one may distinguish the words, "Der Tannenbaum!" "Noel!" "Saints preserve us; it's Christmas!"

The great country that welcomes wanderers remembers to give them cordial greetings when Christmas sees them first upon its shores. The fir tree in the corner of the big, barren room and the ground pine twisted around the pillars are but a part of the cheer provided.

There are relatives and friends to hear some strangers off to their homes. At least half of the chattering, puzzled crowd is lovingly borne away, making the lot of those left behind even more pitiful.

These are those whom the government must send back again or whose relatives have neglected to come for them. When their arrival falls on Christmas, all such are guests of the nation—and the nation is not inhospitable.

Besides the green that tells them what day it is, a feast is provided —the typical American feast, with turkey, celery, and cranberry sauce.

Sometimes, when they have wondered and eaten all they can, a little German Gretchen, her heart overflowing with thanks, begins to hum "Stille Nacht."

Everyone guesses that it is a Christmas hymn, and each sings the hymn of his country softly, making harmony, though it is the feeling, not the time or tune, that is one.

And the Christmas of the immigrants at the barge office is not bad, after all.

Far up in the big city on whose borders the foreigners are being entertained, there is another pathetic group who, like the immigrants, have come unwanted to a land where their lot is destined to be hard.

Yet the sisters who care for the foundlings—the little waifs picked up on sidewalks or left screaming in the basket waiting to receive them at the asylum door—try to make the festival of love and peace comprehensible to their charges.

“The Day When Visitors and Toys and Sweets Ani, Play Are All Theirs Without Restraint.” Drawn by W. O. Wilson. The Puritan, December 1898. | GGA Image ID # 14f53c5c62

Early in the morning, the dormitories where those who have grown beyond the crib stage resound with song. "Carol, Christians, carol carol joyfully," pipe the little voices. And they know that this is the day of days—the day when visitors and toys and sweets and play are all theirs without restraints.

Early in the day, they are summoned to look upon the big fir tree, which holds a gift for everyone. The regular asylum fund provides some of these and some by never-failing Christmas philanthropists.

But the calm-eyed sisters know of some that come from nameless sources, of money, tucked in notes that are not signed, of dolls and toys marked for "Baby Alice" or "Little Joe." Then they know that Christmas has come to awaken conscience and remorse somewhere.

The day ends when the little blue uniformed regiment files into the chapel for vespers—all rosy and devout, full of memories of feasting and frolic—to thank Heaven that they live in a world so kind and fair.

Visitors are gathered in the chapel's body, and they listen pityingly to the thanksgiving of the children, who, all unconscious of the need for pity, "carol joyfully."

Far uptown, in a home overlooking the Hudson, some of the old ladies of New York spend their Christmas. They have looked forward to the clay for many weeks. This one's friends have invited her to dine, and that one's have promised to come and spend an afternoon with her.

The usually quiet place is filled with bustle and confusion from early morning. Little vanities long discarded are resurrected. This one has doubts about the lace collar laid away many years ago; that one is in a flurry over the problem presented by pink and purple ribbons for her cap; another is not sure that her black silk, a relic of former grandeur, will be just the thing for her clay's outing.

The fortunate one who is invited out to dinner is ready several hours before the time set and commiserates patronizingly with the sad little woman whose friends have forgotten that she is in an old ladies' home, to whom no one is coming, who is going nowhere, but who will spend her day in the stiffly decorated rooms, listening to well-meant speeches by the board, joining in perfunctory hymns—all the while alone with her memories.

In all the hospitals, Christmas is the children's day. The aromatic fragrance of pine and fir overpowers the heavy odor of anesthetics for once. Lids that seemed too weary to be lifted from the clay before are wide open now to look upon the fairyland created by the nurses overnight. Over every cot and crib, there is a wreath of green.

On every counterpane are wonders manifold. There is a little bunch of bright, prickly red and green, and the nurses say its name is Holly. For the girls, there are dolls—fine lady dolls for little invalids who have never seen the beings counterfeited for them in wax and tow.

The little girl with a bandaged arm caresses her unresponsive baby with as much instinctive motherhood as though she had two arms. A child croons happily over a shapeless rubber being in the next cot.

Diminutive "nigger" dolls create delight; proud bisque ones inspire awe. And then there are picture books full of gorgeous colors and beautiful scenes, cut and pasted by thoughtful people who treasure cards and magazines to make the pleasure of giving books.

The boys have gifts that appeal equally to them. There are steam engines that will run swiftly over quilts. There are books to make them forget the walls of their wards—jungle tales and desert island stories.

There are toy soldiers to marshal in battle array and to pose for favorite heroes. There are whole villages stacked with houses, animals, bright green trees, and miniature people. All these are enough to make the children forget half their aches and pains—and this is not half their Christmas fun.

If they are convalescing, they may have feasts—such white slices of chicken, such pieces of cake, such beautiful sticks of striped candy, such heaping plates of ice cream.

And in the middle of the ward, for them to gaze at all day long, a fairy tree of green stretches its branches all glittering with tinsel and gay with ribbons, candles, and fruit. In the evening, a bright electric star whirls about and makes them fairly ecstatic with delight.

Almost as lonely as the day of the old lady who has outlived her friends is that of the young woman who has put hers aside for what she probably calls a career.

On Christmas, she bustles into the independent woman's favorite hostelry—the Margaret Louise Home. She does not discard her air of having only a few minutes for such frivolous an occupation as dining, even for this occasion.

But at the table, even the most conspicuously businesslike of the tribe gradually loses her pride of position. She looks, not with unmitigated satisfaction, at the long tables full of others of her kind. The gleam of silver and the white napery do not afford complete esthetic pleasure any more than do the viands, attractive as they are, give her an appetite.

The green hangings she has passed in the sunny parlor make her homesick, and perhaps in all of New York, there is no more depressing sight than the room full of healthy, bright, well-dressed, well-fed, lonely women gathered together away from their kinsfolk.

One has a different feeling about the tramp who has forgotten that he ever had a home and perhaps never did have one worthy of the name. When he slumps into the mission restaurants, his ragged hat pulled low over his eyes; his frayed collar turned up about his ears, unkempt and dirty, one feels grateful that in the big city, there is some Christmas cheer for even the most sad.

Along the waterside and in the narrow, crowded streets of the slums, various missions are established for this day only, restaurants whose open doors mean a welcome to all the outcasts.

For the last three years, some five hundred pounds of turkey and three hundred pounds of chicken have been provided for the five hundred-odd prisoners who happened to be in the Tombs prison at the time. All the jails make equally generous provisions for their inmates.

Prison discipline is relaxed for the day. The women are permitted to walk freely in the corridors all day, and the men are allowed out of their cells until after the noonday dinner.

The dinner is special—not the customary prison stews and potatoes, but one that holds the conventional turkey and cranberry sauce.

The prison missionaries provide entertainment. It would not seem very cheerful, perhaps, to those free to choose their own diversions. But to those to whom each day brings the same dull routine of work or discipline, the Bible reading, praying, and singing of hymns accompany it.

Christmas Day is more than a break in the awful monotony; how much more, one may guess. Who knows that every Christmas Eve, a small band of reclaimed toughs journeys up to a certain house on Madison Square to sing beneath its windows the songs of peace and goodwill its gracious mistress sang to them in prison long ago?

Pauline Stanton, "The Christmas of the Homeless," in The Puritan, Vol. IV, No. 3, December 1898, pp. 326-330

Key Points and Engaging Content 📝

Christmas at the Barge Office 🎄

The article captures a unique Christmas scene at the Barge Office, as immigrants, mostly from Italy and other European countries, experience their first Christmas in America. The surprise of Christmas amid the chaos and uncertainty of immigration adds a poignant layer to their journey. The Barge Office becomes a temporary home for those who have just arrived, providing them with the comfort of a Christmas tree, a festive meal, and a sense of human connection in the middle of their ordeal.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: "And the Christmas of the Immigrants at the Barge Office Is Not a Bad One, After All." – This illustration captures the festive yet somber mood, showing the immigrants in an unfamiliar space, celebrating Christmas with minimal comforts but finding joy in the community spirit.

The Sense of Community and Spirit of the Season 🤝🎁

Despite the gritty realities of their immigrant experience, the immigrants are greeted with the spirit of the season. The article paints a picture of empathy, where even in a government facility, immigrants experience a brief moment of peace. The Christmas feast—including turkey, cranberry sauce, and celery—offers a rare taste of comfort and holiday cheer.

The singing of Christmas carols like "Stille Nacht" symbolizes the universal nature of human connection, transcending language and culture. The simple acts of kindness, such as sharing meals and songs, become a momentary escape from the hardships they face.

📌 Noteworthy Insight: The idea that immigrants from different backgrounds come together to sing their own Christmas carols demonstrates the early stages of cultural assimilation and shared experiences in America.

The Harsh Reality of Detained Immigrants 🚫

The article also focuses on the dark side of immigration at Christmas. While many immigrants are reunited with family or friends, others are left behind to face the government's decision on their fate. The detained immigrants—those who are either rejected or have no one to claim them—spend Christmas alone in the detention pens.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: Visitors, Toys, Sweets, and Playtime for Children – The contrast between the joyful children in the dormitories receiving toys and sweets, while others remain detained, emphasizes the inequities of the immigration system at the time.

The detention of immigrants during Christmas also hints at the uncertainty and prejudice that many faced during their initial days in America. These individuals, despite their hopes for a better life, struggled with the bureaucratic system that determined their future.

The Broader Context of Christmas for the Homeless 🏚️🎅

The article extends beyond the Barge Office, discussing the plight of the homeless, particularly in New York City, during Christmas. It reflects on the larger social issues faced by many during this period, highlighting the loneliness of the elderly in institutions, the impoverished, and even the prisoners in jails.

📌 Noteworthy Insight: The inclusion of prisoners enjoying a festive meal and some temporary freedom on Christmas Day adds an interesting layer to the article. It suggests that, in a city like New York, Christmas was a time of temporary reprieve, even for those at society's margins.

The Impact of Philanthropy and Charity 🎁💰

A key theme in the article is the role of charity during the holiday season. Unclaimed immigrants, the homeless, and the poor benefit from philanthropic efforts, as gifts, donations, and festive meals are made available to them.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: "The Day When Visitors and Toys and Sweets Are All Theirs Without Restraint." – This image depicts the charitable spirit of Christmas, with children in asylums receiving toys and sweets, underscoring how social programs and charitable organizations helped make Christmas a time of joy for the less fortunate.

Educational and Historical Value 🎓📜

📌 For Teachers and Students: This article is a valuable teaching tool for exploring the intersection of immigration, culture, and charity in the late 19th century. It provides rich material for discussions on immigration patterns, assimilation, and the role of Christmas in social welfare. Teachers can use this article to teach students about humanitarian practices and the immigrant experience, using it as a springboard for projects on early 20th-century immigration policies.

📌 For Genealogists: Genealogists researching family members who arrived during the late 1800s will find this article insightful in understanding what their ancestors experienced upon arrival in New York. It can also serve as a useful reference for those researching Italian immigrants, who represented a significant portion of the immigration waves during this time.

📌 For Historians: This piece provides a historical snapshot of Christmas in America and how immigration intersected with social services. It highlights the role of government and charitable organizations in supporting newcomers. Historians can draw connections between the philanthropic efforts discussed in the article and larger societal efforts to help the poor and displaced during major economic transitions in the U.S.

Suggested Improvements and Considerations ✨

While the article does a great job detailing the immigrant experience, more specific anecdotes or firsthand accounts from immigrants would add a more personal and relatable perspective to the story. Personal stories of those detained or assisted during Christmas could bring an even deeper human element to the article.

This article serves as an invaluable historical document that brings together immigration, charity, and the human spirit in a time of hardship. It’s a moving reminder of the resilience of immigrants and the compassion that marked their initial experiences in America.

🔎 Research & Essay Writing Using GG Archives

📢 This is NOT a blog! Instead, students and researchers are encouraged to use the GG Archives materials for academic and historical research.

🔎 Looking for primary sources on Titanic’s lifeboat disaster? GG Archives provides one of the most comprehensive visual collections available today.