Ellis Island: The Hope and Tears of America's Immigrant Gateway

📌 Explore the history of Ellis Island as a pivotal immigration station, where millions of immigrants found hope and faced hardships. This article offers a detailed account of the immigrant experience, the policies that shaped it, and the lasting legacy of Ellis Island in U.S. history.

Ellis Island: Hope and Tears (1986)

Relevance to Immigration Studies for Teachers, Students, Genealogists, Historians, and Others

Ellis Island: Hope and Tears offers a comprehensive historical overview of one of the most significant landmarks in the immigrant experience in the United States. For teachers, students, genealogists, and historians, this article provides invaluable insight into the history of immigration, specifically the processing of immigrants at Ellis Island from its inception in 1892 to its closure in 1954.

The article's detailed accounts of both the difficulties and triumphs of the immigrants as they passed through Ellis Island give readers a balanced view of how the U.S. government responded to the waves of immigrants and the personal hardships endured by those arriving. This content is essential for exploring cultural assimilation, immigration policy, and the evolution of U.S. immigration practices over time.

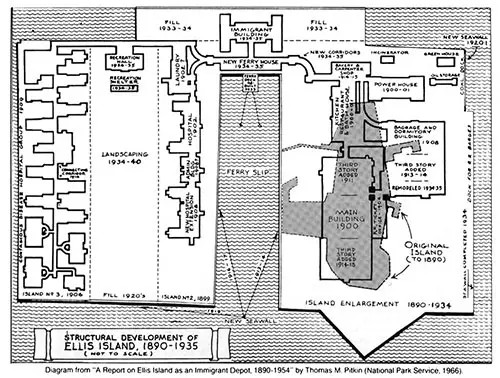

Ellis Island, 1922 with Two Barges Docked in Front of the Main Building. INS Photo by Brown Bros., NY. INS Reporter, Spring 1986. | GGA Image ID # 14b22fbcd0

When the Statue of Liberty became New York's most visible landmark in 1886, most Americans in other states were only dimly aware of her. But because she stood in America's busiest harbor, her majestic figure was the first image of a new home for millions of European immigrants.

The great Atlantic migration began about 1820 and added nearly ten million people to the United States by 1880. By 1890, another five million arrived. According to most estimates, of the 15 million immigrants who came in those 70 years, nearly 11 million came through the port of New York.

It was when whole boatloads of immigrants steamed into New York harbor at an average rate of 1200 per day. Their first stop was the immigration depot at Castle Garden in Battery Park, where they were settled after their long journey and processed for entry into the country.

Castle Garden

Castle Garden was operated by the New York State Board of Emigration Commissioners as a single landing point and processing center for immigrants. It included all the facilities and services necessary to examine and register them, to assist them in finding housing, jobs, and transportation, and to care for the sick and destitute. With everything they needed in one location, the immigrants were protected from swindlers and dishonest labor recruiters seeking to exploit them.

Immigration was still a state responsibility at this time but was moving toward federal control. As the influx of immigrants into the port of New York continued unabated, it was apparent that the Federal Government would need to take control of immigration somewhere other than the outdated and overcrowded facilities at Castle Garden.

The best sites for a new and larger immigration station were three islands in New York Harbor: Governor's Island, Bedloe's Island, and Ellis Island. Ellis Island was chosen, and plans were made immediately to convert it from a naval powder magazine to a Federal immigration station. For that purpose, President Benjamin Harrison signed an appropriation of $85,000 on March 26, 1890.

Castle Garden shut down on April 18, 1890, after processing over eight million immigrants in 35 years of operation. While Ellis Island was being prepared, the Treasury Department assumed full control of the processing of immigrants, taking them in at the Barge Office at the Battery not far from Castle Garden.

Immigration Act of 1891

A year later, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1891, the First comprehensive law for national control of immigration. It created the Bureau of Immigration in the Treasury Department, a pivotal institution that played a crucial role in the transition to federal control. The Bureau placed a Commissioner of Immigration in the port of New York, officially ending state control and processing of immigrants.

One of the Bureau's first actions was to report that the grand and spacious Immigrant Station on Ellis Island, a testament to the scale of the immigration process, was practically completed. The business of receiving and inspecting immigrants would soon be transferred there from the Barge Office, once certain details were arranged.

The Station opened on January 1, 1892. The first immigrant to be admitted was an Irish teenager named Annie Moore. Her arrival marked a significant moment in history, as she was welcomed with ceremonial speeches and presented with a $10 gold piece, symbolizing the hope and opportunities that awaited immigrants in the United States.

Ellis Island Examination Room, 1911. INS Photo. INS Report, Spring 1986. | GGA Image ID # 14b236eb19

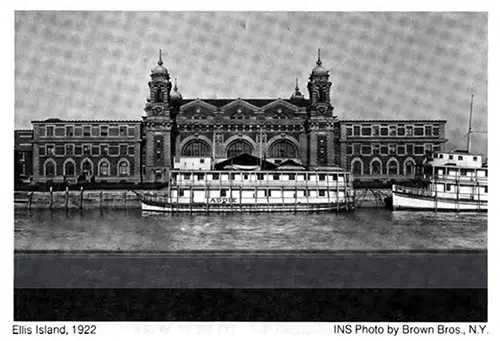

The facilities on the island included a large, two-story administration building, a hospital, a powerhouse, a bathhouse, and some living quarters. The main building, according to a report in Harper's Weekly (October 24, 1891), "looked like a latter-day watering-place hotel, presenting to the view a great many-windowed expanse of buff-painted wooden walls, of blue-slate roofing, and of light and picturesque towers."

A fire swept through the island in June 1897, five years after it opened, and utterly destroyed the original wooden buildings. They were rebuilt in brick and limestone and reopened three years later, but many of the state and federal records lost in the fire could never be replaced. During the rebuilding, immigrants were once again received at the Barge Office.

In the decade after Ellis Island opened, 3,047,130 immigrants arrived at the port of New York. At the same time, only 640,434 came through all other ports of entry.

Immigration peaked during the first decade of the 20th century when 8,795,386 arrived nationwide—6,853,756 (78%) in New York. The year 1907 brought the all-time high of 1,285,349 immigrants to the United States, including 1,004,756 to New York through Ellis Island.

Isle of Tears

As years passed and immigrants passed, Ellis Island took on a character of its own. Depending on when they arrived and how long they stayed at the immigration station, some immigrants would see Ellis Island as an "Isle of Hope," a gateway to freedom and opportunity. But some others would find it an ''Isle of Tears," especially those caught up in the mass migrations of the early 1900s.

At the time when processing took days and even weeks, Ellis Island was a grueling ordeal for the immigrants who were delayed or detained, a nightmare for those who were deported.

The journey from their homelands to the United States was long and arduous. Voyages lasted up to four months, depending on the vessel, and subjected the immigrants to severe mental and physical stress.

At best, they would arrive in America sick, exhausted, and poor. At worst, they would die in steerage or contract smallpox, cholera, or typhus and never go beyond the contagion wards on Ellis Island.

Immigrants who made it to the Great Hall of the main building were greeted by mass turmoil. As one journalist reported, it was a "sea of straining immigrant faces, beards, boots, long overcoats, a babel of languages and dialects, heavily clad women in babushkas clutching in one hand a saucer-eyed child and in the other a knotted bed-sheet bulging with the possessions of the first half or a life. Americans-to-be!"

Immigrant Examinations

Most immigrants agree that the single most terrifying aspect of Ellis Island was the constant fear of being deported. They had to undergo physical and mental examinations to determine who was eligible to enter the country and who would be sent back.

The physical exam was known as the "six-second medical." Immigrants formed two lines and made their way up the massive staircase past the medical inspectors to the Great Hall. Doctors hid behind the wall next to and near the top of the stairs so they could observe the immigrants without being seen.

Immigrants would be watched and marked with chalk if they had suspected illnesses. An "H" chalked on an immigrant meant they had heart trouble, an "L" meant lameness, "E" was for eyes and possible trachoma, "S" stood for senility, "Pg" meant pregnant, "Sc" indicated a scalp condition, possibly lice, and a circle with a cross in the middle meant feeblemindedness and automatic deportation.

One immigrant wrote of the fear of being deported, "I will always remember the huddled frightened people, the terror of being shipped back. I remember sitting on those wooden benches with my mother saying, 'Don't act funny, don't say anything foolish,'" fearing they would be suspected of being mentally unbalanced.

Ellis Island "looked like a latter-day watering-place hotel, "according to a report in Harper's Weekly in October 1891.

The mental exam took two minutes and was a mental competency check. Immigrants were asked their name, occupation, age, place of birth, history of mental illness, marital status, and destination.

Most immigrants gave acceptable answers and were tagged with a numbered ticket indicating the railroad line in the direction they were headed.

A recruiting center was opened on Ellis Island for immigrants to sign up for the armed forces during the war years. This would benefit the immigrants as well as the country.

Surprisingly, a good number joined. After the war, a referral service was set up so that immigrants could get jobs before leaving the island. Approximately 200 immigrants used the service per day and found jobs rather quickly.

The processing of immigrants was an enormous undertaking. With up to 5,000 immigrants passing through Ellis Island every day during the peak years, immigration officials often had to work long hours continuously examining aliens. Some examiners reportedly dealt with 400 a day.

Still, most immigrants made it through in only a few hours. As one journalist described, "If they could prove they weren't diseased or feebleminded, could support themselves, and knew where they were headed, they were free to step through the final, longed-for green door marked PUSH TO NEW YORK."

Early Immigration Reform

The Federal immigration station on Ellis Island marked the first genuine attempt at regulating immigration precisely when some regulation was most needed. After immigration rose to an all-time high between the turn of the century and the First World War, Congress took action to try to control it.

The Immigration Act of 1917 established a literacy test for the first time. It made the existing mental and physical examinations even more challenging.

New health requirements were implemented, excluding persons with contagious diseases or histories of mental illness. Also, due to World War I, security regulations were enacted. These things helped curb the tremendous flow of immigrants into the country.

The number of immigrants dropped sharply from 1.2 million in 1914 to an average of about 300,000 during each of the war years to only 110,000 in

1918. At the same time, the proportion of immigrants arriving in New York dropped below 50 percent for the first time in history, amounting to 47% of the U.S. total in 1916, 44% in 1917, 26% in 1918, and only 19% in 1919.

When immigration rose again to 430,000 in 1920 and 805,000 in 1921, Congress enacted legislation in 1921 and 1924 to limit the number of aliens allowed into the country. These laws imposed the first substantial restrictions on the flow of immigrants by setting numerical quotas for admissions by nationality.

At the same time, American consulates abroad started screening prospective immigrants at their points of origin so that only those immigrants requiring further examination came to Ellis Island. The rest were taken to the mainland, and the number of people passing through the island continued to decrease.

The Great Depression marked the first time in history that immigrants outnumbered immigrants.

The Great Depression marked the first time in history that emigrants leaving the United States outnumbered immigrants coming in. It triggered a decline in both the number of arrivals and admissions. Fewer aliens dared to come, and many who tried were denied visas because they lacked adequate means of support.

During 1933, for example, only 23,000 aliens were admitted—21,000 in New York—and more than 80,000 departed. In the same year, a record number of illegal aliens—nearly 20,000—were deported for the sake of many jobless Americans.

Due to decreasing immigration and increasing deportations, Ellis Island lost the name "immigration station." It became a detention center for excludable or questionable aliens.

During the year of lowest immigration and highest emigration, 1933, about 4,500 incoming aliens were detained on the island until they were found to be admissible, usually after three or four days, and more than 7,000 outgoing aliens were held there to await deportation.

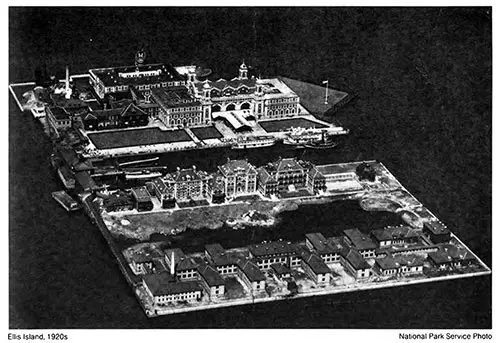

Diagram from "A Report on Ellis Island as an Immigrant Depot, 1890-1954" by Thomas M. Pitkin (National Park Service, 1966). INS Reporter, Spring 1986. | GGA Image ID # 14b27c79ad. Click to View a Larger Image.

Economic recovery brought an upward trend in immigration until 1940, when war broke out in Europe and forced another decline. The low point came in 1943, well after the United States joined the war, when fewer than 24,000 immigrants arrived, and the detention center on Ellis Island housed German, Italian, and Japanese enemy alien civilians. The island was also used as a Coast Guard station during the war.

The war years 1941-1945 brought fewer than 40,000 immigrants through New York Harbor, a mere 23% of the 171,000 immigrants who came to America during that period.

Declining Years

Even when immigration picked up again after the war, the use of the island tapered off rapidly. When the Coast Guard left in 1946, the Attorney General wrote to the Commissioner of Public Buildings: "Owing to high operating costs, I deem it imperative that the Immigration and Naturalization Service vacates its quarters on Ellis Island in New York harbor at the earliest possible date." But because of its excessive amount of space, inconvenient location, and costly upkeep, no other agency wanted it. It remained open as a detention and deportation center.

The end of Ellis Island began in 1950 when it began processing immigrants again. The passage of the Internal Security Act of 1950 required immigrants to be screened for membership in Communist or Fascist groups, so aliens arriving in New York were taken to Ellis Island for that purpose.

In 1951, almost 143,000 of the 206,000 aliens who came to America went through Ellis Island, and the number of detainees there increased from 400 to 1200 on a daily average.

The renewed examinations and increased detentions brought a flurry of criticism from the press, which persuaded Congress to revise the law and end the requirement for screening aliens who already held visas.

Ellis Island then reverted to a detention facility, and INS began to renovate and repair the long-neglected buildings. After several significant improvements were made, however, INS changed its detention policy and released most detainees on parole unless they were "likely to abscond." The population of Ellis Island dropped

From a few hundred on November 1, 1954, to about 25 ten days later, INS closed it along with other large detention centers. The last alien was dispatched from the island on November 12, 1954.

As a result of the new detention policy, more than 200,000 aliens entered the U.S. through the port of New York between November 1954 and June 1955. Still, only 16 of these were detained in local facilities in Manhattan.

After the INS moved out of Ellis Island, the General Services Administration (GSA) declared it surplus government property. It was offered for sale to the highest bidder in 1956. They were, in turn, swamped with bids ranging from 50 cents to over a million dollars.

Many suggestions were made regarding Ellis Island's future. The issue was divided between those who were interested in preserving the island for its historical value and those who wanted to see it serve a more practical function.

During its conversion from arsenal to (immigration) depot, the island had to be enlarged to accommodate more buildings.

GSA received many proposals for the island, including an international cathedral, a maritime museum, a nursing home for veterans, a center for the mentally disabled, a college for exceptionally talented students, housing for the elderly, a facility for the care and training of needy youth, and an entertainment spot with theaters and restaurants.

The fate of the island was difficult to decide because of its romantic history. However, in I960, President Eisenhower took Ellis Island off the commercial bidding stand because of its "sentimental attachment as a gateway to the nation." He strongly opposed converting the island into a commercial piece of property.

As a result, the island was virtually abandoned until a plan for its use could be formulated. While it stood idle, the island's only inhabitant was "Millie," a four-year-old female Doberman pinscher watchdog. She guarded the island against vandals at night and was joined by a human guard during the day. Except for these two, Ellis Island was left unused and untended.

As the island lay dormant for 10 years, the immigration rate remained relatively steady at about 282,000 annually. Of that number, 131,000 (47%) were coming through New York in sight of the Statue of Liberty and the crumbling immigration station.

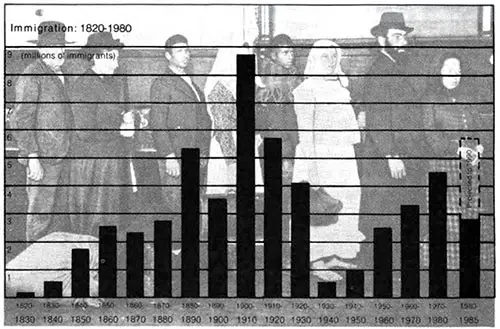

Graph Showing Immigration for the Years 1820 to 1980. INS Reporter, Spring 1986. | GGA Image ID # 14b29947d6. Click to View a Larger Image.

National Monument

On May 11, 1965, President Johnson placed Ellis Island under the care of the Department of Interior's National Park Service. With a $6 million down payment from Congress, he declared Ellis Island an integral part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument.

Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall suggested making Ellis Island a public memorial where more than 100 million Americans could trace their roots today. To further celebrate Ellis Island's new status as a monument, a bill was signed in October 1966, providing for the striking of an Ellis Island medal.

As public awareness and concern grew, groups began forming to raise additional money for the island. Peter Sammartino, founder and once chancellor of Fairleigh Dickenson University in New Jersey, started the "Restore Ellis Island Committee" to gain money from Congress and raise public consciousness. Within a short time, he had recruited fifty representatives from various ethnic groups in the U.S.

In 1976, Congress appropriated $1 million to prepare the island for public opening. In June of the same year, ferry services began shuttling tourists back and forth.

President Reagan announced the formation of the Statue of Liberty Ellis Island Centennial Commission in 1982. The Commission was created to raise money to restore and preserve the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island and to plan celebrations upon each project's completion.

A goal of $230 million was established to cover the estimated cost of repairing and rededicating the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. Of the total, $108 million is earmarked for Ellis Island and $62 million for the Statue of Liberty for restoration and preservation.

The statue will be wholly restored, and Ellis Island's seawall will be rebuilt along with many of her buildings to create an elaborate immigration museum for the public. Also, of the remaining $60 million, $20 million will go toward the ongoing maintenance of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, $28 million will be used for education and celebrations, and the final $12 million will cover administrative and campaign costs.

Immigration After Ellis Island

The pattern of immigration has changed dramatically since the heyday of Ellis Island. New York City has remained the largest port of entry. Still, its proportional share of immigrants dropped steadily from a high of 76% of the nation's total in the first decade of the 1900s to below 30% in the 1970s. During the same period, the percentage of immigrants who came to the West Coast rose from less than one percent to nearly 25%.

Immigrants who crossed the southern border from Mexico accounted for a scant 1.5% of the total in the years before 1911 but for 15% after 1970. By comparison, those who entered from Canada represented a relatively stable proportion, increasing only slightly from 7% to 9% in the same period.

These changes were brought about more by circumstance than by design. For example, the growth of air travel shifted significant entry points from seaports to airports. Social, economic, and political conditions in Europe, Asia, and Central America moved the main avenues of migration from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the Caribbean. And the rapid development of cities in southwestern states drew more migrants away from traditional eastern destinations.

However, many changes resulted from legislation and government policy, beginning with the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952. Congress passed this comprehensive legislation over President Truman's veto to consolidate all previous immigration and nationality laws into one statute.

Although it continued the national origins quota system and tightened the existing security and screening procedures, this law established the basis for many policies that remain in effect today. Generally, these policies have been less restrictive than the ones they superseded.

Aerial View of Ellis Island circa 1920s. National Park Service Photo. INS Reporter, Spring 1985. | GGA Image ID # 14b31e990f

Partly because of the law's more liberal posture, immigration rose from 170,000 in 1953 to 327,000 in 1957. It leveled off to below 300,000 per year in the late fifties and early sixties, but generally, an upward trend had been established. The decade ending in 1960 brought in 2.5 million immigrants—more than twice as many as those who came the previous decade.

The trend continued after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which became fully effective in 1968. It abolished the quota system and set up annual numerical limitations of 170,000 immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere and 120,000 from the Western Hemisphere, with no more than 20,000 from any nation.

Several preference categories were established for those subject to the numerical limitations to further balance admissions. The numerical restrictions did not apply to immediate relatives of U.S. citizens or particular classes of special immigrants.

The most significant effect of the 1965 legislation was the surge in Asian immigration, which increased 100% in one year, from less than 20,000 in 1965 to 40,000 in 1966. From 1966 to 1970, about 320,000 immigrants were admitted from the Philippines, China, India, Korea, Japan, and other Asian and Middle Eastern nations.

Along with the immigration growth came a rise in the number of refugees who came to America after 1954. Besides the hundreds of thousands of persons displaced by World War II and the Korean War, these refugees included 38,000 Hungarians who escaped after their attempted revolution in 1956 and 22,000 victims of earthquakes and floods in the Azores and Indonesia in 1958. Also, the United States admitted some 264,000 Cuban refugees between 1966 and 1975 and more than 137,000 Indochinese refugees between 1977 and 1980.

These numbers were in addition to regular immigration totals, which reached a total of 4.5 million in the decade ending in 1980. This continued growth in the number of aliens coming to America was due to the greater acceptance of refugees and changes in the law, which eliminated differences between Eastern and Western Hemispheres, immigrant ceilings, and preferences.

With the 1980s came a new administration and new efforts in Congress to reform immigration law. In 1981, President Reagan announced an immigration policy based on eight principles:

- To continue America's tradition of welcoming people from other nations and sharing the global responsibility of resettling those who flee oppression.

- Ensure adequate legal authority to enforce the laws and control U.S. borders.

- To reflect in law and policy the special relationship with Canada and Mexico.

- To recognize the mutual benefit of Mexicans working in U.S. areas with special labor needs.

- To recognize the contributions of illegal aliens who have become productive U.S. residents and give them legal status without encouraging more illegal immigration.

- To improve the government's ability to establish and carry out an immigration and refugee policy with a more balanced nationwide impact.

- To seek new ways to integrate refugees into society without nurturing their dependence on welfare.

- To recognize the international scope of immigration and refugee problems and to seek greater international cooperation in solving them by promoting economic development and reducing motives for illegal migration.

These principles were reflected in immigration reform legislation (formerly known as the Simpson-Mazzoli Bill) passed by the Senate in 1982 and again, with revisions, in 1985. The proposed law would relax some restraints on legal immigration but mainly would strengthen control over illegal immigration.

It includes provisions to discourage unlawful entry by raising penalties for alien smuggling and fraud and by imposing sanctions on employers who knowingly hire undocumented aliens, to improve programs permitting aliens to be brought in as temporary workers, and to extend legal status to undocumented aliens who have lived in the U.S. since January 1, 1980.

The proposal is still under discussion in both houses of Congress. When this summary was written, some action was expected before the 1986 summer recess, although further postponement is still possible. In the meantime, immigration has continued at a rate of well over half a million per year, totaling nearly 2.3 million from 1982 through 1985.

As President Reagan said when he introduced his administration's immigration policy in 1981, "Immigration and refugee policy is an important part of our past and fundamental to our national interest. With the help of Congress and the American people, we will work towards a new and realistic immigration policy. This policy will be fair to our citizens. At the same time, it opens the door of opportunity for those who seek a new life in America!"

Kathleen P. Barry, "Isle of Hope, Isle of Tears," in the INS Reporter, U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, Vol. 34, No, 2, Spring 1986, pp. 7-13.

Key Highlights and Engaging Content

Ellis Island's Role as "The Gateway to America"

The article highlights the historical significance of Ellis Island as a symbol of hope and new beginnings for millions of immigrants. From its opening in 1892, it processed over 12 million immigrants before it became a detention center.

This provides crucial insight into how Ellis Island was not just a processing station, but also a beacon of opportunity. The symbolic connection between the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island is explored in depth, particularly how these landmarks represented freedom and prosperity for newcomers from Europe.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: Ellis Island, 1922 with Two Barges Docked in Front of the Main Building – This photograph captures the busy nature of Ellis Island at the height of immigration, with barges bringing in thousands of immigrants, symbolizing the scale of immigration during that era.

The Dual Experience of Ellis Island: Isle of Hope vs. Isle of Tears

The article poignantly describes how Ellis Island was viewed differently depending on one's immigration experience. For many, it was an "Isle of Hope," representing new opportunities and freedom. However, for others who were detained, inspected, or deported, it became an "Isle of Tears," filled with frustration, uncertainty, and fear.

The juxtaposition of these two perspectives provides a complex view of the immigrant experience at Ellis Island, showing that while many found success, others faced hardship, delays, and even separation from their families.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: Immigrant Examinations – This image offers a glimpse into the intense scrutiny immigrants underwent upon their arrival. The image is evocative of the emotional toll the process took on immigrants, particularly those subjected to the fear of deportation or detention.

The "Six-Second Medical" and the Fear of Deportation

One of the most gripping sections of the article focuses on the medical and mental examinations that immigrants had to undergo. The "six-second medical" was a feared ordeal where immigrants were examined for physical conditions that might disqualify them from entering the U.S., such as trachoma, lame, or heart disease.

This process, which led to many being sent back, underscores the stress and anxiety felt by immigrants, as well as the stringent policies governing who could enter the U.S.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: Ellis Island Examination Room, 1911 – This image emphasizes the clinical and impartial nature of the examinations, reinforcing the cold reality that many immigrants faced during this critical moment of their journey.

Economic and Legislative Changes Impacting Immigration

The article also touches on the economic and political factors that influenced immigration during the 20th century, particularly the Immigration Acts of 1917, which set up a literacy test and implemented more stringent health checks.

The legislation shifted the U.S. from a period of open immigration to one of more controlled entry, reflecting growing concerns about the impact of immigration on American society.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: Aerial View of Ellis Island circa 1920s – The aerial perspective of Ellis Island during its peak years as an immigration processing center highlights the scale and efficiency of operations, contextualizing the massive challenge faced by officials and immigrants alike.

The Decline of Ellis Island and Its Legacy

The article transitions from the heyday of Ellis Island to its eventual decline as the center of immigration processing. Following the Great Depression and World War II, the flow of immigrants decreased, and Ellis Island was repurposed as a detention and deportation center.

The 1950s saw the end of Ellis Island’s use for immigrant processing, and the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island became more symbolic than functional.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: Diagram from "A Report on Ellis Island as an Immigrant Depot" – This diagram is essential for understanding the layout and organization of Ellis Island, which plays a role in showing how the infrastructure was designed to handle the waves of immigrants during its operational years.

Educational and Historical Insights

Understanding the Immigrant Experience

This article is an excellent resource for students and historians who wish to explore the human aspect of immigration, showing both the dreams and struggles of those who sought a better life in America.

The emotional journey through Ellis Island, from hopeful arrival to tedious inspections, offers critical insights into the challenges immigrants faced, as well as the policies that shaped their experiences.

Impact of Legislation and Reform

The historical context provided regarding early immigration reform (such as the Immigration Act of 1917) and the effects of World War I on immigration policy is valuable for understanding the evolving nature of U.S. immigration laws. This can benefit genealogists and immigration researchers who are tracing their ancestors’ immigration paths.

Ellis Island as a Symbol

The article’s reflection on Ellis Island as both an "Isle of Hope" and an "Isle of Tears" encapsulates the dual nature of the immigration experience in America.

It serves as a critical example for teachers and students to explore immigration as a complex, multifaceted journey, influenced by economic, social, and political factors.

Final Thoughts

Ellis Island: Hope and Tears offers a rich historical perspective on the immigrant experience, blending personal stories, statistical data, and political shifts.

It provides a comprehensive narrative that is ideal for educators and researchers aiming to study the evolution of U.S. immigration policy, the human impact of immigration laws, and the legacy of Ellis Island as both a gateway and a barrier.

The images and personal accounts effectively bring to life the multifaceted challenges immigrants faced when arriving in the U.S.

🔎 Research & Essay Writing Using GG Archives

📢 This is NOT a blog! Instead, students and researchers are encouraged to use the GG Archives materials for academic and historical research.

🔎 Looking for primary sources on Titanic’s lifeboat disaster? GG Archives provides one of the most comprehensive visual collections available today.