Immigrants at Ellis Island in 1913: Health, Stories, and Immigration Policies

📌 Explore the stories of immigrants passing through Ellis Island in 1913, including their emotional journeys, the medical inspection process, and the evolving policies that shaped immigration. A detailed account for students, educators, and historians.

Immigrants Going Through Ellis Island in 1913

Relevance to Immigration Studies for Teachers, Students, Genealogists, Historians, and Others

Immigrants Going Through Ellis Island in 1913 offers an invaluable perspective for those studying immigration, particularly during the early 20th century.

For teachers, the article provides rich content for classroom discussions, particularly in U.S. history and immigration policy. Students studying sociology, history, or public health will find the examination of the immigrant experience, the medical inspection process, and the broader social implications to be deeply informative.

Genealogists can appreciate the details of the immigrant journey through Ellis Island and the personal stories embedded within, helping to understand their own family history.

For historians, the article is a powerful lens into the changing dynamics of U.S. immigration policy, social attitudes, and the challenges of managing immigration during a time of rapid industrialization and evolving societal norms.

By Dr. Alfred C. Reed, U. S. Public Health Service, Ellis Island

It is a thought-provoking question whether the visitor to Ellis Island observes the newly landed immigrant with eyes any more curious than those with which the immigrant regards the visitor. Both are engaged in a mutual learning process, each offering a unique perspective.

The immigrant, in his first moments at Ellis Island, is a bundle of emotions-timidity, surprise, fear, and expectation. These feelings are a testament to the enormity of the journey he has undertaken.

Main Immigration Building at Ellis Island. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e21f8d43

It is a busy island. Yet in all the rushing hurry and seeming confusion of a full day, in all the babel of language, the excitement and fright and wonder of the thousands of newly landed, and in all the manifold and endless details that make up the immigration plant, there is system, silent, watchful, swift, efficient.

Five thousand immigrants in a day is no uncommon figure. Five thousand six hundred passed through last Easter Sunday. Five hundred and twenty-five persons are employed on the island, exclusive of the score of medical officers and the hundred or more attendants of the Public Health Service.

The Immigrant Hospital at Ellis Island. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e2254cde

It is an island crowded with pathos, tragedy, startling contrasts, and unexpected humor. A burly, laughing giant of a man came down the line one afternoon, elated to have reached the land of his lifelong hope. The following day, he lay stricken with meningitis and, that evening, was dead.

A young mother was separated from her two-year-old baby because the baby had diphtheria. In a few days, the baby died, and the mother went on alone to the father waiting in the west.

The reunion of broken families and the old folks coming to live in the home prepared by the pioneer children constantly afford views of human nature unmasked and unrestrained.

All races and conditions of men come together here and adjust themselves more or less amicably to each other. Children with no common bond of race, language, or religion play together more happily for that reason.

Some have been here for months. In the New York room, a Flemish couple have waited seven long months for a little girl who is still sick in the hospital.

Every morning on his rounds, they ask the doctor how soon she can come to them, and thrice a week, they visit her bedside. Perhaps by now, their long waiting is finished, and she has happily gone on with them to her new home in America.

A Polish Mother Holding Her Baby Up To See The Doctor. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e26b4ce4

America, a nation shaped by immigrants, has seen a significant shift in its immigration patterns over the past thirty years. While the principal increase in population has historically been due to immigration, the character of that immigration has now changed markedly.

Prior to 1883, Western and northern Europe sent a stalwart stock, 95 percent of all who came. They sought new homes and became settlers.

Scandinavians, Danes, Dutch, Germans, French, Swiss, and the English islanders were the best of Europe's blood. They were industrious, patriotic, and farsighted.

These early immigrants were not just settlers, but also productive and constructive workers. They transformed barren lands into thriving communities, mined resources, and built infrastructure, ensuring their children received a quality education and instilled in them a love for their new home.

However, the immigrant tide has flowed increasingly from eastern and southern Europe for three decades. The others still come, but they are far outnumbered by the Jews, Slays, the Balkan and Austrian races, and those from the Mediterranean countries.

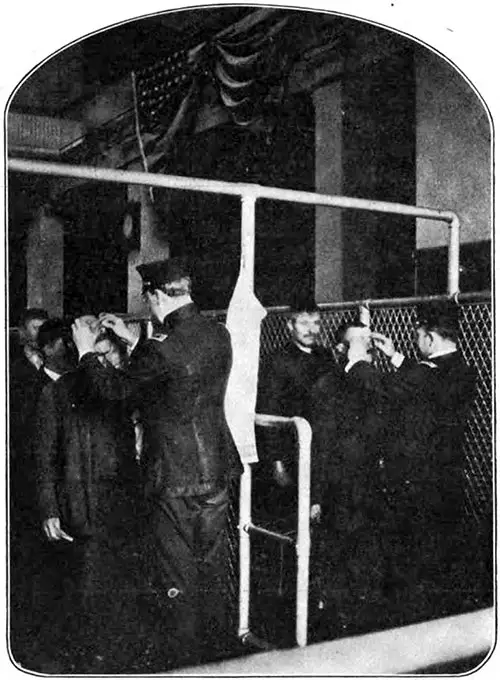

Examining Eyes on the Line at Ellis Island. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e304831a

In contrast with earlier immigration, these people are less inclined to transplant their homes and affections. They come to make what they can in a few years of arduous, unremitting labor and then return to their homes to spend it in comparative comfort and ease.

It has been well said that America is their workshop and Europe their home. Thirty percent of them return to their former homes.

Class members contribute little lasting value but work in their hands for which they are well paid. From what they earn, they send home no minor pact. In 1907, they sent $275,000,000 out of the country.

This money was earned, but its greater value in investment and development was lost. In contrast to their predecessors, the immigrants since 1883 tend to form a floating population.

They do not amalgamate. They are here in no small degree for what they can get. It is not always true that they come to supply an actual demand.

The periodical advertisement of a national demand for cheap labor does not spring from an actual economic need, even though the influx of cheap labor might put more money in the employer's pocket.

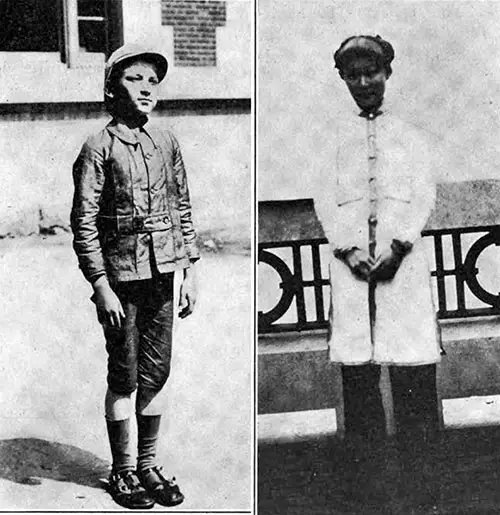

Russian Immigrant Girls at Ellis Island. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e353c321

Such is the type of newer immigration, and its changing and deteriorating character makes restriction justifiable and necessary. No one can stand at Ellis Island and see the physical and mental wrecks who are stopped there or realize that if the bars were lowered ever so little, the infirm and mentally unsound would come literally in hordes without becoming a firm believer in restriction and admission of only the best.

The average citizen does not realize the enormous numbers of mentally disordered and morally delinquent persons in the United States nor to how great an extent these classes are recruited from aliens and their children. Restriction is vitally necessary if our truly American ideals and institutions are to persist and if our inherited stock of good American manhood is not to be depreciated.

This restriction can be made operative at various points, but the medical requirement is the key to the whole situation. No alien is desirable as an immigrant if he is mentally or physically unsound, while mental and physical health, in the broad sense, carries with it moral, social, and economic fitness.

The present United States immigration law (legislation of 1907) is very definite in its statement of medical requirements for admission.

A Russian Jewish Boy, Just Landed (l) and A Chinese Girl in the Detention Quarters. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e359d030

The law divides physically and mentally defective aliens into three classes. Class A includes those whose exclusion is mandatory under the law because of a specified defect or disease. In this class are idiots, imbeciles, people with epilepsy, the feebleminded, insane, and those subject to tuberculosis or a dangerous or loathsome contagious disease.

When a medical diagnosis of these conditions has been made, that person is automatically excluded. In Class B are conditions not mentioned in Class A but which make the person affected liable to become a public charge or affect his ability to earn a living.

Class C includes defective and diseased conditions not included under A or B but must nevertheless be certified for the information of the immigration officials.

Officers of the United States Public Health Service inspect all immigrant aliens medically. This service dates from an act of Congress in 1798 creating the original Marine Hospital Service, which conducted hospitals at all large ports and inland waterway cities for seamen of the American merchant marine.

The service's duties have since been enlarged to include all features of national health protection. Its officers rank equal with those of the army and navy medical corps and are found worldwide pursuing investigations and carrying out measures to protect the public health of the United States.

The medical inspection of immigrants is one of many important of their functions. The Bureau of Immigration is under the Department of Commerce and Labor. At the same time, the Public Health Service is under the direction of the Secretary of the Treasury.

Eighty-two immigration stations encompass the entire United States coastline and frontiers, allowing aliens to enter the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii.

During the fiscal year 1911, the total number of immigrants examined was 1,093,809. Of these, 27,412 were certified for some mental or physical defect. The most critical entry point is Ellis Island, where 749,642 aliens were examined. Nearly 17,000 medical certificates were issued here, and more than 5,000 of these were deported.

The Ellis Island station of the Public Health Service has 25 medical officers attached, including six specially trained in diagnosing and observing mental disorders. Their work is divided into the boarding division, the hospital, and the line.

The boarding division has its offices at Battery Park, N. Y. Utilizing a fast and powerful cutter, The Immigrant, these men meet all incoming liners as they leave the New York Quarantine Station and start up the bay.

Their inspection is limited to aliens in the first and second cabins. Those who require a more careful and detailed examination are sent to Ellis Island. The others are discharged at the dock after passing the additional inspection of the Department of Commerce and Labor.

At the dock, all third—and fourth-class aliens are transferred to barges, each carrying about 700, and taken to Ellis Island.

Ellis Island is located near the Statue of Liberty on Bedloe's Island, about a mile from Battery Park. It is the most commanding location in New York Harbor.

It consists of a tiny natural island and two additional artificial ones, connected with the first by a covered passageway across the intervening strip of water. The main immigration station is on the first island, and the hospital division of the medical service occupies the other two.

One is the general hospital, and the other is the contagious hospital, which consists of separate pavilions connected with open-covered passageways.

Each hospital can accommodate approximately 200 patients at once, and it is usually fairly full. The service is limited strictly to aliens, and the expense of each immigrant receiving hospital care is charged to the steamship company that brought him.

This hospital is excellently conducted; every method of most approved diagnostic, surgical, and medical techniques is practiced. A rare variety of diseases is seen. Patients literally from the farthest corners of the earth come together here.

Rare tropical diseases, unusual internal disorders, strange skin lesions, and the more frequent cases of a busy general city hospital present themselves.

The Matron and Some of Her Charges on the Roof at Ellis Island. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e35d5c1e

The variety of contagious diseases is unusual, and the physicians in charge must have extreme diagnostic skills. In the fiscal year 1911, over 6,000 cases were treated in the hospital, exclusive of 720 cases transferred to the Quarantine Hospital at the Harbor entrance before the completion of the present contagious hospital on Ellis Island.

The third division of the medical inspection is "the line," or primary inspection. This is the part that the island visitor sees and has often been described.

Suffice it to say that as the immigrants leave the barges, they pass in single file before the medical officers who pick out all who present evidence of any mental or physical defect. They are turned aside into the medical examining rooms for more careful observation.

Each defect or disease receives a medical certificate signed by three physicians, which places the bearer in one of the three classes already mentioned.

Those who require immediate medical or surgical care for any reason are transferred to the hospital. Certain cases require longer observation and more detailed examination for diagnosis. Examples are tuberculosis, parasitic scalp diseases, mental disorders, and trachoma.

Having been certified or passed clear in the medical division, the immigrant, along with those from the barge who have not been turned aside, goes to the upper or registry floor for the immigration authorities' inspection.

These inspectors ask the same questions that the immigrant was required to answer when the ship's manifest was filled out before embarkation.

This covers such information as name, age, destination, race, nativity, last residence, occupation, condition of health, nearest relative or friend in the old country, who paid his passage, whether in the United States before, whether ever in prison, whether a polygamist or anarchist, whether coming under any contract labor scheme, and personal marks of identification such as height, and color of eyes and hair. Any discrepancies in the answers are noted.

The immigrant is also required to show what money he has. All who do not satisfactorily meet these questions or who hold medical certificates of classes A or B are held for a rigid examination before a Board of Special Inquiry, which decides whether or not they shall be admitted.

Each of these boards consists of three members, and the decision of two members is final. The hearings of the hoards are private, but a complete copy of the proceedings is made and filed in Washington.

Those who are to be deported are held on the island until the vessel on which they came is ready for its return voyage. In the event of deportation being ordered, the alien may appeal the board's decision to the commissioner of the port, from him to the commissioner-general of immigration, and then to the Secretary of Commerce and Labor.

Immigrant Family's First Photograph Taken at Ellis Island. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e379d75b

Those immigrants who have passed satisfactorily and are bound for New York City are sent to the " New York room " to await friends or responsible parties who come for them.

This is one of the island's most dramatic and thrilling spots, for it is the reunion place of friends, relatives, and lovers. The Irish girl who came two years ago meets her sister and the old mother.

The one is pale, nervous, and clad in New York apparel; the others have never seen the ocean until their good ship sailed, and their brilliant cheeks and country dress are in keeping with their dense ignorance and shyness.

They know the price of shoes and what spuds are worth at the market, but it is beyond them to recall the date of their birthday or the present month.

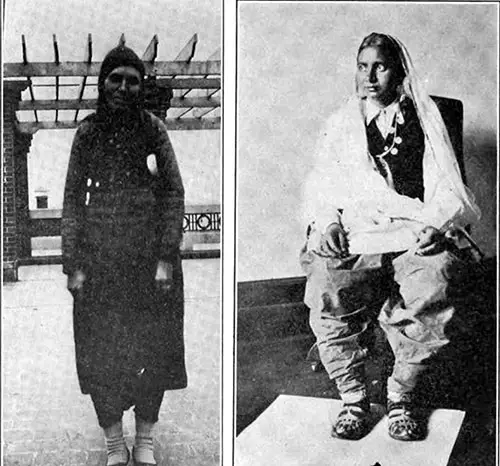

A Serbian Woman (left) and a woman from Hindustan Wearing a Genuine Harem Skirt. Photographs taken at Ellis Island. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e3a8181e

Immigrants destined for destinations other than New York City are sent to the railroad room. Here, they exchange their money for United States coins and buy their railroad tickets under careful supervision.

Their baggage is checked, they have a telegraph, cable, and post office, and they may buy lunches whose contents are displayed in glass cases to all.

Special agents see that each one buys a lunch proportioned to the size of his family and the length of his journey. Cigars, cakes, and fruits are also to be had.

One day, a stolid and emotionless Slavish woman opened her cardboard lunch box at the bottom and extracted a piece of bologna cut on the bias, smelled it carefully from different sides, licked it, finally tasted it, and then broke into a flood of smiles as she pressed it forcibly into the mouth of her equally stolid two-year-old baby. And the baby sucked and munched on the new world dainty in undiscerning pleasure!

But the greatest mystery in the lunch box is usually the tiny round fruit pie. Some carefully raise the crust and extract the contents with a much-used finger.

Another whittles it off in slices with a murderous knife a foot in length, while another will carefully eat off all the crust and discard the interior. A bearded Cossack with great care and patience chewed a hole through one corner of a tin of sardines.

Then with praiseworthy perseverance, he sucked out the oil! From the railroad room, the immigrants are taken in barges to the railroad depot on which their journey will be made.

Immigrants who are to be deported or who, for any reason, must remain on the island for some time are placed in detention quarters, which are not open to visitors.

Tiers of beds are provided, accommodating 1,800 persons, but often this number is exceeded by 500. These quarters are among the most interesting points on the island.

The women and children of all races and tongues are in one large room, and the men in another. In mild weather, they are all sent onto the fine, broad roof of the building.

Not long ago, a Danish woman who could speak no English and whose baby was in the hospital with diphtheria became a second mother to a coal-black pick-a-ninny, who had come up from Trinidad on a coffee ship and whose mother was also in the hospital.

Again, race wars occur among the children, and Turks and Armenians will battle ferociously with Italians. Mention should be made of the large immigrant dining room, which seats 1,100, where the missionary societies hold a polyglot Christmas entertainment each year.

However, the observer at Ellis Island sees only the immigrant stream flowing in. He needs to see what results are distributed throughout the country. No graver questions are before the American nation today than those associated with immigration and none whose correct solution demands more imperative attention.

One of these vital questions, which is in special prominence just now, is the relation of immigration to mental disorders. This question concerns New York state more acutely than other states only because New York has the largest number of alien defectives.

In February 1912, there were 33,311 committed insane cases in New York state institutions.

It is estimated that more than 8,000 of these, or roughly 25 percent, are aliens, and this is exclusive of those conditions of mental defectiveness listed under idiocy, imbecility, and feeble-mindedness.

About 7,000 distinctly feeble-minded children are in New York schools, or about 1 percent of the school population. Again, this does not include idiots and imbeciles to an equal number, not attending school, nor border-line cases, and morally defective children.

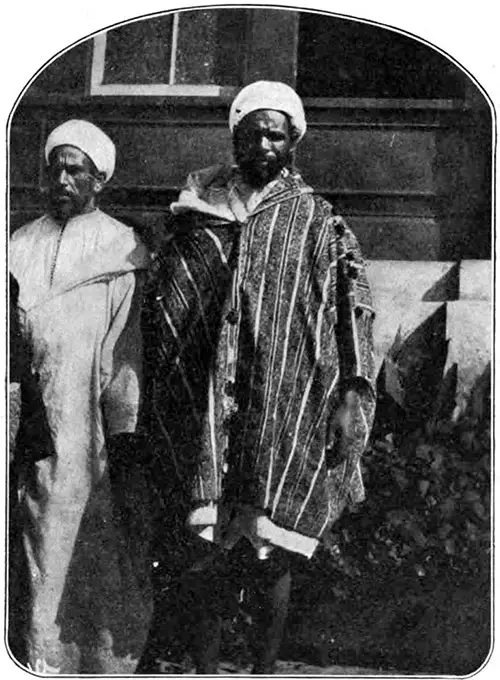

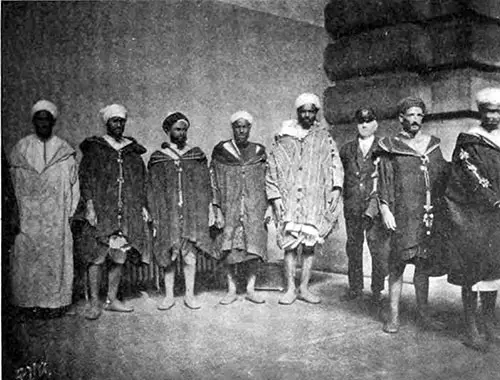

Two African Arabs, Awaiting the Medical Examination. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e3f05e0a

The total number of feeble-minded children in New York is about 10,000. According to the figures of the last census, 30 percent of the feeble-minded children in the general population throughout the country are the progeny of aliens or naturalized citizens. Thus, the presence of 3,000 of New York's feeble-minded children can safely be attributed to immigration.

These figures show the extreme necessity of careful medical inspection of immigrants. But there are many complicating factors. It is challenging to recognize many types of insanity. It is almost impossible to detect feeblemindedness in infants and young children.

Yet despite this, the medical officers at Ellis Island are doing thorough and practical work and do not deserve the ignorant criticism of those unfamiliar with its difficulties.

Unfortunately, criticism is valid regarding the deportation of aliens who, within three years after landing, show themselves subject to any of those conditions which the law excludes or who become public charges from any cause, said condition or cause having existed prior to landing.

Berbers from Algeria - Filling an Engagement at a New York Theater. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e4007c00

If the present entrance inspection were reinforced by a determined administration of these deportation laws, and if all cases whose exclusion the law makes mandatory and which are now certified by the medical officers were actually excluded, there would be little cause for complaint. But such a condition does not exist.

The medical officers have nothing to do with passing judgment on whether an immigrant should be admitted or not. Their province alone is to certify his physical and mental status. The question of admission, as well as of deportation, rests with the officials of the Department of Commerce and Labor.

Controlling organic physical diseases, such as hookworm infection, is much easier. The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission's survey of the prevalence of hookworm disease throughout the world shows that this infection belts the world in a zone 66° wide with the equator near its middle and that practically every country in this zone is heavily infected. Evidently, a grave danger lurks in immigration from any country where the hookworm is prevalent.

Among the worst afflicted countries is India, with an estimated 60 to 80 percent of the population of 300,000,000 harboring this parasite.

This leads to peculiar interest in the movement of Hindu coolies into the United States in the last few years. A shipload of these coolies landing recently in San Francisco was found by the health authorities of that port to have 90 percent. Infected with hookworm.

An Italian Immigrant Family -- a Mother and Five Children. The Popular Science Monthly, January 1913. | GGA Image ID # 14e4577514

Every colony and camp of Hindus in California today is a dangerous source of infection to all the country around. A rigid quarantine has been established against further importation of this class of aliens.

There are numerous other questions besides those that have been touched on here. Immigration presents one of the most serious problems facing this country. Ellis Island is where the country's needs and dangers in this regard are focused.

Its ever-changing stream of humanity furnishes a fascinating realm for the student of human nature and the study of the great questions of economics and eugenics.

Dr. Alfred C. Reed, "Going Through Ellis Island," in The Popular Science Monthly, New York: The Science Press, Vol. LXXXII, No, 1, January 1913, pp. 5-18.

Key Highlights and Engaging Content

The Human Side of Ellis Island

The article opens with a compelling observation: the mutual curiosity between immigrants and visitors to Ellis Island. This sets the tone for exploring the emotional and psychological complexity faced by the newly arrived.

The immigrant’s bundle of emotions—timidity, fear, excitement—makes the experience all the more poignant and relatable.

Personal Stories of Tragedy and Hope

The stories shared, like the tragic tale of a young mother separated from her baby who later dies, and the joyful reunion of families, humanize the immigrant experience.

These personal anecdotes are powerful teaching tools for educators discussing the intersection of human emotions and immigration policies. They also provide genealogists a poignant context for understanding their ancestors' potential struggles.

Medical Inspection and Challenges at Ellis Island

The in-depth description of the medical inspection process at Ellis Island provides insight into how physical and mental conditions influenced immigrant admissions.

It’s fascinating to learn about the challenges faced by medical staff, especially when dealing with highly contagious diseases such as hookworm, prevalent among immigrants from certain regions.

The detailed descriptions of health procedures are invaluable for students studying the public health measures of the time.

Noteworthy Images and Captions

🖼 "Main Immigration Building at Ellis Island" – This historical image gives context to the bustling and complex nature of Ellis Island, providing a visual reference for readers to imagine the immigrant process. It connects the written content to the physical setting.

🖼 "A Polish Mother Holding Her Baby Up To See The Doctor" – This image is both tender and powerful, symbolizing the immigrant mother’s vulnerability and the role of the medical officers in determining the fate of each individual.

🖼 "Russian Immigrant Girls at Ellis Island" – This photo showcases the diversity of immigrants coming through Ellis Island, underscoring the ethnic and cultural melting pot that was shaping early 20th-century America.

Economic and Social Implications of Immigration

The article discusses how the immigrant labor force shifted after 1883, with many Eastern and Southern Europeans arriving in the U.S. to work temporarily before returning to their homelands.

The economic ramifications of this “floating population” that sent significant portions of their earnings back home provide an important lesson in understanding the impact of immigration on both the U.S. economy and the sending countries.

Educational and Historical Insights

Immigrant Health and Screening

The detailed examination of the medical screening process, including the importance of mental health evaluations and the challenges of detecting diseases like tuberculosis and trachoma, is essential for understanding the evolution of public health policies and their integration into immigration law.

This offers a crucial historical insight into how health concerns influenced policy and the lives of immigrants.

The Role of Ellis Island in Shaping U.S. Immigration Policy

The focus on the legislative framework that governed Ellis Island—such as the medical exclusion laws—offers students and historians valuable context about how U.S. immigration policies were enforced and how they changed over time. The article also reflects the growing nativist sentiments and concerns about the "mental and moral fitness" of immigrants.

Social and Cultural Integration

By exploring the diverse ethnic groups arriving at Ellis Island and the efforts to integrate them into American society, the article sheds light on the early challenges of Americanization.

It highlights the evolving understanding of what it meant to be "American" and how immigrants navigated the complexities of identity in a new land.

Final Thoughts

Immigrants Going Through Ellis Island in 1913 is a deeply engaging exploration of the experiences faced by immigrants at one of America’s most iconic immigration stations. The combination of personal stories, medical insights, and social commentary provides a nuanced understanding of immigration during the early 20th century.

For educators, historians, students, and genealogists, this article serves as a rich source of information, offering both historical facts and personal narratives that bring the immigrant experience to life.

While the article presents a vivid account of the time, it also raises important questions about the human cost of immigration and the policies that shaped the immigrant experience.

The exploration of medical, social, and cultural factors at Ellis Island provides a multifaceted view of the role immigration played in shaping the United States.

🔎 Research & Essay Writing Using GG Archives

📢 This is NOT a blog! Instead, students and researchers are encouraged to use the GG Archives materials for academic and historical research.

🔎 Looking for primary sources on Titanic’s lifeboat disaster? GG Archives provides one of the most comprehensive visual collections available today.