Americans In The Raw: The Struggles of Immigrants at Ellis Island (1902)

📌 Explore the journey of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island in 1902, from their possessions and wealth to the hardships of quarantine, detention, and labor. This article offers a rich historical account of the immigrant experience in early 20th-century America.

Americans In The Raw - Immigrants at Ellis Island (1902)

Overview and Relevance to Immigration History 🌍📜

The article Americans in the Raw - Immigrants at Ellis Island from The World's Work offers a comprehensive and vivid portrayal of the immigrant experience at Ellis Island in the early 1900s, highlighting the intense influx of immigrants, their struggles, and their initial steps in America. Written by Edward Lowry, the piece serves as both a historical snapshot of immigration practices and a deeply human exploration of the immigrant journey. With photographs by Arthur Hewitt, this article provides rich context for teachers, students, genealogists, historians, and anyone interested in the immigrant experience, making it a valuable resource for understanding how this wave of immigrants shaped both their lives and America's development.

The article is especially relevant as it describes the immigrant inspection process, detailing the personal possessions, money, and personal stories of those who arrived. It also delves into the challenges faced by immigrants—from harsh working conditions to the exploitation they encountered in the streets of New York. For genealogists, it offers an excellent snapshot of the diverse origins of immigrants and the procedures they underwent, helping to build a clearer understanding of ancestral immigration during this period.

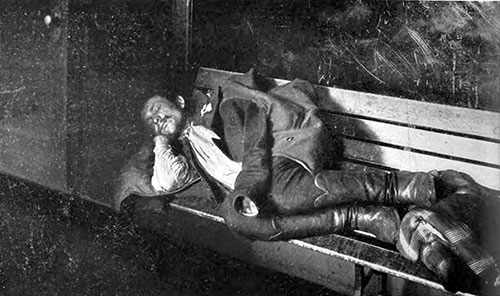

Immigrant Detained for Special Inquiry at Ellis Island. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f7ecd3ca

The High Tide of Immigrants-Their Strange Possessions and Their Meager Wealth - What Becomes of Them

By Edward Lowry; Illustrated From Photographs by Arthur Hewitt

In an open ditch, red and raw under a broiling sun, sixty-five Italian immigrants, stripped to the necessities, toiled silently with a shovel and pick.

A hard-faced, red-necked man, their taskmaster, walked up and down the trench, and wherever he stopped, the men worked with feverish speed. Temporarily, at least, this will be the fate of thousands of the other immigrants who flowed in through Ellis Island in this year's spring flood —the greatest in twenty years.

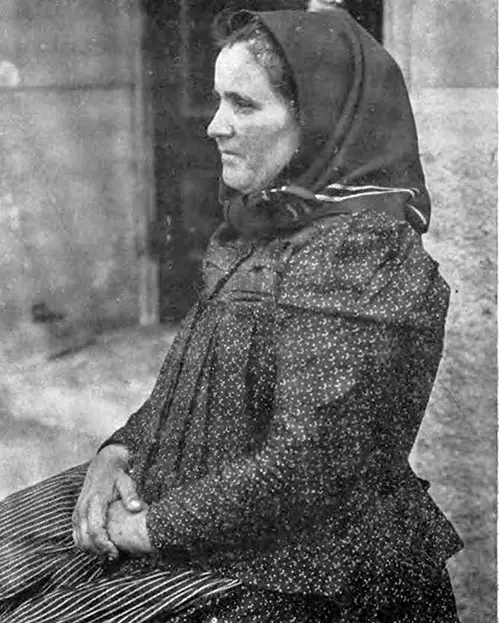

Immigrant Woman from Holland at Ellis Island. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f81b53d1

During the fiscal year ending June 30, 1901, 388,931 immigrants were landed in New York; 92,485 were landed in May alone, and 6,491 were landed on one day in May. The highest previous monthly record in twenty years was in May 1893—the flood is always heaviest in spring—when 73,000 were landed.

Polish Immigrant Woman at Ellis Island. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f830fb92

Persons with contagious or incurable diseases are sent back, and a far greater number of others on the ground that they are likely to become public charges. The others give their occupations and enter, but not always to take up the occupation given, for many calling themselves musicians have been found later working as waiters in restaurants or toiling as laborers on public works.

Woman and Child Waiting in one of the Railway Detention Rooms at Ellis Island. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f854ef00

The Government assumes jurisdiction over the aliens as soon as their steamer has been passed at quarantine. Inspectors go aboard from the revenue cutters down the bay and obtain the manifests of alien passengers, which the steamship companies must supply. These manifests must show the following:

- Full name—age—sex—

- Whether married or single—

- Calling or occupation—

- Whether able to read or write—

- Nationality—

- Last residence —

- Seaport for landing in the United States—

- Final destination in the United States—

- Whether having a ticket through to such a destination—

- Whether the immigrant has paid his passage, or whether it has been paid by other persons, or by any corporation, society, municipality, or government—

- Whether in possession of money, and if so, whether upward of $30, and how much, if $30 or less—

- Whether going to join a relative and, if so, what relative and his name and address—

- Whether ever before in the United States and if so, when and where—whether ever in prison or almshouse or supported by charity —

- Whether a polygamist—

- Whether under contract, expressed or implied, to perform labor in the United States—

- The immigrant's condition of health, mentally and physically, and whether deformed or crippled; and if so, from what cause.

It is a searching census, indeed.

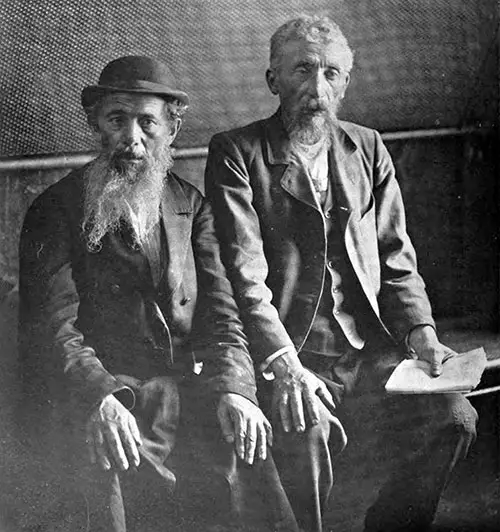

Two Male Immigrants Wait in the Detention Pen - Men Who Will Be Deported as Not Desirable. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f8bcb15e

When the steamship reaches its pier, the inspectors discharge such immigrants as they may deem unnecessary to examine (usually not more than fifteen or twenty).

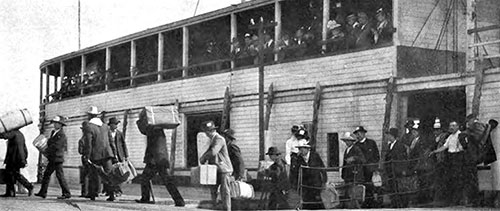

All the others are transferred to barges and taken to Ellis Island. There, on the main floor of the big immigration building, they are divided into groups, according to the manifests, and separated.

Later, in lines set off by iron railings, they undergo " primary inspection." Each immigrant is questioned to see if his answers tally with the manifests. If they do, he is discharged; if they do not, he is detained for "special inquiry" by boards composed of four inspectors, who decide all questionable cases. Only the Secretary of the Treasury can overrule their decision.

The immigrants are kept in the big detention room downstairs until the railway agents take them to board trains to their final destinations. While on the island, the Government lodges them, and the steamship companies feed them.

My concern has been not with the larger meaning but with the unkempt particles of this slow and constantly moving glacier of humanity, from whence and why they came, how much money they brought with them, and the amount and character of their baggage, how they procured employment, and how they were assimilated.

Odd Baggage of the Immigrants

I welcomed Florio Vincenzo when he came over to become one of us. He had no doubts about the future, for he boldly wooed the Goddess of Good Fortune. Florio is fourteen; lie came from Palermo.

He traveled light. When he opened his cheap paper valise, it was empty, save for a pair of discredited and disreputable old shoes. Florio bowed, cap in hand, and his white teeth flashed as he smiled suavely: " I am a poor man, nobleman, seeking my fortune."

Young Irishmen Ready for Politics. World's Work, July 1902. | GGA Image ID # 1500378256

An old inspector knew there was an odor. He picked up one of the shoes and extracted, after some manipulation, a creased and crumpled hunk of Bologna sausage. The other shoe was stuffed with a soft, sticky, and aggressively fragrant mass of Italian cheese.

These items, along with a sum of Italian money equivalent to about $1.80 and the clothes he wore, formed the basis on which Florio expected to rear his fortune.

Pietro Viarilli was gray-haired, round-shouldered and weakened. He, too, had come to make his fortune. His impedimenta consisted of one padlocked canvas valise lined with paper and containing two striped cotton shirts, one neckerchief of yellow silk with blue flowers and edges, one black hat (soiled and worn), one waistcoat, two pairs of woolen hose of gay design, one suit of underwear, one pint of olive oil and about half a peck of hard bread biscuits.

Until his arrival, the list included a quart of Vesuvian wine of the rich purple hue one may buy in cheap cafes in Naples. Carelessly, Pietro had slung his valise from his shoulder and smashed his bottle, drenching his store of biscuits. He and his companions had munched them greedily until the supply was exhausted.

The contents of the bags and boxes of the Scandinavians, English, Scotch, and Irish are usually more diverse. These immigrants bring over articles of personal adornment or household ornaments of sentimental interest. The Scandinavians bring more baggage than any others. Close behind come the English and the French.

Roughly speaking, those from the North of Europe bring more personal effects than those from the South. The 2,000 immigrants who arrived on a Liverpool ship one morning this summer brought 1,185 checked baggage, exclusive of about 900 hand baggage.

This is about two-thirds more than the same number of persons from Southern Europe would have brought. For this reason, Hungarians, Slovaks, Greeks, Sicilians, and other South-of-Europe peoples, are called " walkers " by baggage men.

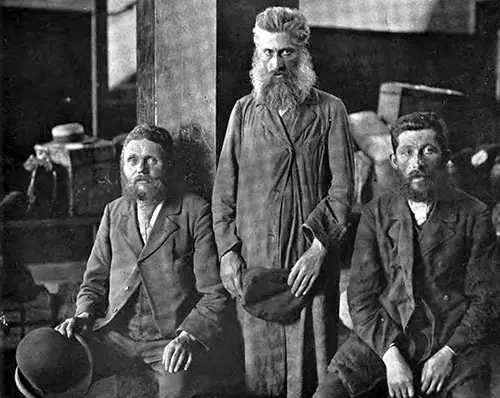

Russian Jewish Immigrants at Ellis Island. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f8dee81a

During one month this spring, 21,367 pieces of baggage were received at Ellis Island, examined, and sent to various parts of the country. The baggage was frail, poorly made, and awkwardly shaped, much of it unmarked and the rest scrawled over with undecipherable hieroglyphics.

The Government makes no charge for storage, and if he chooses, the immigrant may leave his trunk or box on the island for a year, yet seldom a piece is lost.

It is said that the old customs inspectors could tell at a glance from a bag's contents just what part of Europe its owner had come from. The Italians bring wine, fruits, oil, or nuts; the English and Scotch will have a piece of tweed or heavy cloth, and the Irish bring frieze.

In the main, however, these immigrants come away from their homes to a strange country, bringing less clothing and fewer personal effects than the average American workingman would drag out of a burning house and choose about as wisely.

MONEY BROUGHT BY THE IMMIGRANTS

At the examination, the immigrants are asked to show their money. Some craftily fail to show it all; others willingly display their petty hoardings. The money is carefully counted and restored to them after a record has been taken.

Later, they are asked if they wish for any money to change. Many refuse for fear of being cheated; others stop before the busy money-changers booth at the end of the long examination room.

Last year, the 388,931 immigrants showed $5,490,080, an average of $14.12. The French surpassed all the others with an average of $39.37. The Hebrews stood at the bottom of the list, bringing on an average of $8.58. The Germans followed the French with an average of $31.14.

The other nationalities stood in the list as follows:

| Race | Average Per Capita |

|---|---|

| Italians (northern) | $ 23.53 |

| Bohemian and Moravian | 22.78 |

| Scandinavian | 18.16 |

| Irish | 17.10 |

| Armenian | 15.75 |

| Croatian and Dalmatian | 15.54 |

| Greek | 15.10 |

| Slovak | 12.31 |

| Magyar | 10.96 |

| Italian (Southern) | 8.67 |

One afternoon, a pleasant-faced little man with trustful blue eyes stood before the desk. His wife, a typical German woman, and three children formed a patient waiting group behind him.

The man wore a suit of stained and worn "copperas jeans, " top boots, and the high-peaked cap of the German peasant.

He was fumbling through his pockets and in the hidden recesses of his garments, producing money. Thalers, marks, Imperial treasury notes, and gold pieces fell from his dirty fingers until a tidy little heap lay on the counter.

Some of the immigrant officers looked on in amazement. The little German had seemed peculiarly unproductive soil for such a harvest, which amounted to over $600, which was to be converted into United States treasury notes.

He grinned cheerfully when the neat pile of crisp green bills was handed to him and, opening his shirt, stowed the roll where he could feel it next to his body. But he was an exceptionally wealthy immigrant.

The Immigrants As Citizens

Getting a job is a casual business with an immigrant. Each finds an opportunity. In a big gray stone building on the Battery is a low living room with white walls —bare save for rows of benches. In one corner is a railed-off desk space where two or three kindly-faced older men sit. An iron railing running the length of the room separates capital from labor.

A Typical Italian Immigrant Family at Ellis Island. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f9097c8d

On the benches are men waiting to be hired, of all sorts but alike, with no friends and no work. They slouch like habitual park loungers. A dull spirit of lethargy hangs over the room.

The waiting peasants read dirty scraps of newspapers or chat disconnectedly. Employers come in from time to time and tell the man behind the railing their needs. A fair-faced blond man in shirt sleeves, for example, came in one day and spoke briefly:—

" Who wants to work for a baker ? " called the manager.

A young fellow stood up like a boy at school, came forward, and talked with the employer in German. Then he went back and sat down. Another man looked up from his paper and spoke to the baker, and the two departed, chatting like old friends.

This bureau, maintained by the German Society of the City of New York and the Irish Emigrant Society, employs 1,000 to 1,500 people monthly. However, immigrants usually rely on friends or relatives for a start.

Peasants from Norway on the Roof at Ellis Island Awaiting Deportation. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f926aa32

Women seeking domestic service are more inconsistent than men. They will not take a place outside of New York, not even in Brooklyn, but they can get higher wages in New York than in any other place in the country.

Foreigners in this country for less than one year are still subject to the immigration laws. If an immigrant becomes a public charge within twelve months or applies to a public charity for relief, he is deported at the expense of the steamship company. The Outdoor Poor Bureau, maintained by the City of New York, handles about zoo° such cases every year.

The case of "Prince" Ranji T. Smilie was interesting. The " Prince " came into New York as an Eastern potentate with a retinue of swarthy retainers. He was only a curry cook, and his coming had been cleverly exploited to advertise an Oriental restaurant where the " Prince " was to cook and the retinue would become waiters. When the restaurant failed, the waiters applied for relief and were sent to Ellis Island. Later, they were deported.

Immigrant Waits at Ellis Island Until Her Friends Arrive. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f95c1c43

Some other cases have had interesting features: Ado Tokian, who described himself as a minister, was thirty-one years of age and did not know what ship he came on (not an uncommon occurrence). He applied for relief in June. He had $.5.00 when he landed nearly a year previously and $3.00 at the time he made his application.

He had been refused on a similar application last September, so he returned to the mainland and enlisted. He was discharged in June. In less than a month, he was " broke. "

Another case was that of an English girl, an idiot, and a person with epilepsy who was here for a little more than a year. Her sister gave the unfortunate girl a good home, but circumstances recently made it impossible to support her longer.

When she applied at the Outdoor Poor Bureau, it was found that she was a British subject and could not be permanently committed to an institution here because she had been in this country for more than a year. The British Consul refused to do anything. The outcome of the matter is yet to be determined.

Two Swedish Immigrant Girls on Their Way to Wisconsin. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f9ae759e

Roughly speaking, the people of the North of Europe are better citizens than those from the South of Europe. The better class goes to the country, and the worst goes to the cities.

The Greeks are considered the least desirable of all; the Italians from the southern portion of the peninsula also make poor citizens, but those from the northern part of Italy rank with the Swiss and other desirable nationalities.

According to a recent Census Bulletin, over 19,000,000 immigrants landed in the United States from 1821 to 1900. Germany sent 5,000,000; Ireland, 3,870,000; Great Britain, 3,026,000; Scandinavia, 1,246,000; Austria-Hungary (including Bohemia), 1,000,000; and Italy, 1,000,000. Once, the stream came mainly from the North of Europe; now, it comes chiefly from the South—from undesirable countries.

Coming to a New Land in Her Old Age. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14f9c658bd

However, these Greeks and the Southern Italians, who live by selling fruit from the push carts in the city streets, earn considerable sums of money. An old Italian was detained at Ellis Island, preparatory to being deported because he had arrived here penniless.

He sent for his son, a push-cart man, who had been in this country just one year. The boy (under twenty) brought his bank book showing deposits aggregating $250.

This money represented the sum he had saved. He impressed upon the inspectors his ability to support his father, and the older man was admitted. The boy said his expenses were about $7.00 a week and that he did not work for a padrone but was an independent merchant.

Others follow different paths and have strange adventures. I shall call Karl Ritter a man now honored in a Western State. His older brother emigrated from the Black Forest to Wisconsin, where, laboring and living frugally, he acquired a prairie farm.

At age eight, Karl came over with his name stitched on a square of white cloth on his breast. Kindly men cared for him until he reached Black Earth on a dreary winter day.

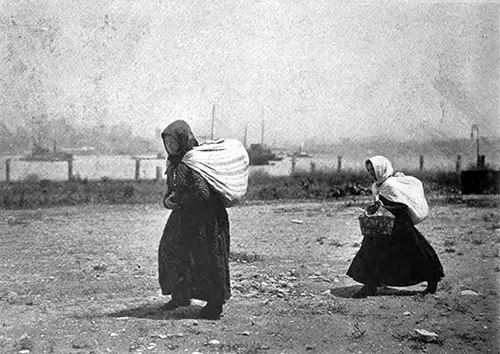

Polish Immigrant Women Going from a Barge to the Immigration Building on Ellis Island. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14fa68bb30

When the day's work was over, the station agent drove him over the dull prairie to his brother's place and left him at the gate. He knocked, but getting no response, he pushed desperately in.

An older man and woman with sinister, vicious faces sat in the little farmhouse and told him his brother had gone on a journey. After a fortnight, beaten down with terrors, Karl ran away and, tramping up country, secured a place on a farm.

Arrived at manhood and owner of a farm of his own, he was called one day to Black Earth to learn that the man and woman he had met the day of his arrival had murdered his brother the day before and hidden the body in the cellar.

Immigrants Landing on Ellis Island. The Immigrants are Brought in Barges from the Ships to the Island. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14fb560442

I have heard another odd tale. Three Scandinavian immigrant boys were each left on a sixty-acre prairie farm by their father. Mons was a fisherman—the more he thought, the plainer he saw his duty. To Nils, he said:

" If I give you my farm, will you support me so I can fish ?"

Now, Nils's 120 acres have increased to several thousand, and his stock is the finest in the country. Mons fishes all day in the lake, seldom catching anything but content with his lot.

Released Italians Waiting for the Boat to Take Them to New York. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14fb8d46c7

The final destination of the hordes pouring in can be set down roughly, though the objective point of all the newcomers is a part of their record. Of the '38,000 arrivals in May and June of this year, the distribution of the largest streams flowing in from Ellis Island was as follows:—

- New York City and State 59,786

- Pennsylvania 24.499

- Illinois 8.445

- Massachusetts 8,781

- Connecticut 5,870

- New Jersey. 6,598

- Ohio 4.862

- Michigan 2,592

- Minnesota 2666

Only a portion of the Italians came as permanent settlers. Of the 533,245 immigrants from Italy in 'go,' 281,688, according to their declaration, sought temporary employment to return to their old homes.

There were 20,221 temporary immigrants. They have shown no tendency to settle in "colonies" but seek work wherever it may be had at tolerable wages.

Dutch Peasants at Ellis Island -- Mother, Son, Daughter-in-Law, and Grandchild Come to Make a Home in the West. Photograph by Arthur Hewitt. The World's Work, October 1902. | GGA Image ID # 14fbabea77

Unlike the Swedes, Danes, and Finns, they usually go directly to Western lumber camps and farms. Even these, like many of the immigrants, retain their old home customs years after settling, and outward-bound ships in the spring are filled with two-—and three-year-old immigrants going home on visits. As soon as the coal strike began in Pennsylvania, thousands of the strikers went back to Europe.

Certain foreign-born residents of New York visit the Battery Park sea wall in the spring because of homesickness. On sunny mornings, the long rows of benches facing the sea are full of men and women with bright headdresses and gaily colored shawls watching the ships come in.

They chat animatedly, and their manners are vivacious. They talk of home, Tuscan hillsides, vineyards, Cretan villages, and old Mediterranean cities.

At regular intervals, when the boat from Ellis Island brings its load of newly arrived immigrants to the Barge Office, there is a rush of the homesick ones to the edge of the sea wall.

The peasants on the boat wave their hats or brilliant neckerchiefs, and sometimes, there is a greeting call from across the water. Those who sit on the benches do not go to the park for the clean, cool air but to satisfy psychological demands.

Edward Lowry, "Americans in the Raw," in The World's Work: A History of Our Time, New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, Vol. IV, No, 6, October 1902, pp. 2644-2655.

Key Points and Engaging Content ✨

The Immigrant Journey and First Impressions 🛳️👀

Lowry describes the arrivals at Ellis Island, focusing on the spring flood of immigrants—a peak period in the early 1900s. With nearly 390,000 immigrants arriving at New York during the fiscal year ending in 1901, the article captures the vast scale of this migration. These immigrants came from all over Europe, seeking new opportunities in America.

The emotional impact of the immigrant experience is vividly portrayed, with many described as dazed, silent, and helpless, not yet fully understanding what America had in store for them.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: "Immigrant Detained for Special Inquiry at Ellis Island" – This image captures the solemnity of the immigration process, where immigrants are detained for further questioning. It emphasizes the seriousness of the screening process and the uncertainty immigrants often faced.

Immigrant Possessions and Wealth 💼💰

The article humorously and poignantly highlights the strange possessions immigrants brought with them—often little more than clothing, food items, and small personal keepsakes. For example, Florio Vincenzo, a 14-year-old boy from Palermo, arrived with old shoes stuffed with food like bologna sausage and cheese, symbolizing the poverty many faced and their resourcefulness.

Lowry also discusses the baggage immigrants carried, contrasting the wealthier immigrants with those who arrived with barely $15 to their name. The money immigrants brought was another crucial aspect—most brought only a few dollars, but some, like the German immigrant, were more financially prepared.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: "Immigrant Woman from Holland at Ellis Island" – This image portrays the individuality of the immigrants and their varied backgrounds, showcasing their personal journey to America.

The Immigrant Experience at Ellis Island 🏙️🚶♂️

Once on Ellis Island, immigrants went through a rigorous screening process. This included primary inspection where immigrants' answers were checked against their manifests, as well as more intensive questioning by inspectors. Those who didn’t meet requirements—whether due to health concerns, lack of money, or a questionable background—were detained or sent back.

The article offers a glimpse into the bureaucratic machinery of Ellis Island and the immigrant detention process, discussing how officials handled cases of sickness, fraud, and discrepancies in the manifests.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: "Two Male Immigrants Wait in the Detention Pen" – This image reveals the emotionally charged waiting rooms of Ellis Island, where detained immigrants were isolated and processed.

Immigrant Jobs and Integration 💼🌍

Lowry also delves into how immigrants found employment in America. Many found work quickly, relying on labor recruiters or local job markets. However, the immigrant workforce was often exploited, forced to work in squalid conditions for low wages, as depicted by the Italian immigrants working on labor-intensive projects under harsh conditions.

The article notes that many immigrants did not find jobs in their declared professions but ended up working in low-wage sectors. This speaks to the difficulty of assimilation and the gap between expectation and reality for immigrants in America.

🖼 Noteworthy Image: "Young Irishmen Ready for Politics" – This image stands as a symbolic representation of how immigrants, particularly the Irish, eventually integrated into American politics.

Educational and Historical Value 📘🔎

📌 For Teachers and Students: This article is an excellent resource for discussing immigration history and the human side of this massive social phenomenon. Teachers can use it to explain the procedural aspects of immigration at Ellis Island, the cultural diversity of immigrant groups, and the personal stories behind these numbers.

📌 For Genealogists: This article gives context to the challenges and experiences that immigrant ancestors might have faced. Understanding the immigration process and the economic realities many immigrants encountered can provide deeper insight into family history research.

📌 For Historians: The article offers rich qualitative data on the immigrant experience at Ellis Island. The photographs and personal anecdotes help to understand the socioeconomic trends, health regulations, and cultural shifts during a pivotal time in American history.

Final Thoughts 🌟

Americans In The Raw offers a vivid, heartfelt account of the immigrant experience at Ellis Island, drawing attention to the human side of immigration.

Through detailed photographs, personal anecdotes, and sociological observations, it provides teachers, students, and genealogists with a nuanced understanding of the immigration process at one of the most iconic gateways to the United States.

The article serves not only as a historical document but also as a reflection on the personal struggles, sacrifices, and aspirations of immigrants who helped shape modern America.

🔎 Research & Essay Writing Using GG Archives

📢 This is NOT a blog! Instead, students and researchers are encouraged to use the GG Archives materials for academic and historical research.

🔎 Looking for primary sources on Titanic’s lifeboat disaster? GG Archives provides one of the most comprehensive visual collections available today.