Ellis Island: Three Perspectives on Immigration and Military Mobilization in 1918

📌 Explore the stories of Army nurses stationed at Ellis Island during World War I, shedding light on the dual role of the island as both an immigration gateway and military mobilization center.

Ellis Island from Three Points of View

Relevance to Immigration Studies

Ellis Island from Three Points of View is an intriguing piece that offers diverse perspectives on the Ellis Island experience, particularly during World War I. The article is essential for teachers, students, genealogists, historians, and others exploring the intersection of immigration, military service, and the role of women in wartime.

Through the eyes of three women involved in Army nursing duties, it also provides a unique perspective on Ellis Island’s military mobilization efforts and the human aspect of the immigration process during a critical time in history.

Ellis Island Dock with Immigrants in Background circa 1915. National Photo Company. Library of Congress, LCCN 89707154. | GGA Image ID # 2194685d67

By Flora A. Graham

The quota of nurses from Base Hospital 33 celebrated Washington's Birthday by entraining at different points for mobilization at Ellis Island, New York. About twenty came from Albany, others from Schenectady, Troy, and some from cantonments where they had been in Army service while waiting for mobilization.

Those from Albany were given a very pleasant ovation at the depot by the Red Cross and by our many friends who gathered there to wish us the best of luck. We were generously supplied with bonbons, fruit, flowers, and everything our friends could think of to cheer us on our way.

We marched to the train carrying United States flags and the gift of the Red Cross while the band played that most popular air, "Johnny Get Your Gun." We had a pleasant, uneventful trip and reached our destination about six o'clock in the evening, an exhausted, travel-worn group of women. We were immediately ushered into the dining room, where we enjoyed our first Army dinner.

We have nothing but good reports regarding the food provided for us during the three weeks we have spent here; it is clean, wholesome, and abundant, much better than expected. After dinner, we were shown to our dormitories, which were large, spacious rooms, each one accommodating about twenty nurses.

We lost little time in getting comfortably settled. So, our first day in Uncle Sam's service passed pleasantly, and as our beds were very comfortable, we were soon in the land of dreams.

We are situated on Island No. 3. This group of islands, numbered 1, 2, and 3, has connecting bridges over which we walk many times each day to our meals, the post, and the ferry boat landing.

The administration offices are on Island No. 1. There is also an immense hall where the Y. M. C. A. very kindly provides amusements three times a week for soldiers and sailors; an invitation has also been extended to Army nurses.

These amusements consist of motion pictures, lectures, and popular and patriotic songs and are appreciated and primarily attended. On one occasion, I noticed the boys were incredibly enthusiastic over the song, "Mother, Bid Your Baby Boy Goodbye." The screen picture was Tom Sawyer, and it was all pleasure.

All aliens entering the United States, whether cabin or steerage passengers, must pass through Ellis Island, and while formerly these were inspected and examined on the island, a new Act of Congress, which went into effect February 5, requires these examinations to be made on shipboard, or at the steamboat dock, before landing. Consequently, the service of a large corps of officers is required.

Under normal conditions, these numbers are about 650, including 150 medical officers and hospital attendants. The hospital is on Island No. 3, where large pavilions are reserved for mobilizing Red Cross units. There are several units here, and all are being rapidly equipped for overseas service. The equipment is acceptable, complete, and very good-looking, and we are very proud to wear our new spring suit with its symbol of honor.

Different organizations have entertained us very nicely. The Red Cross of New York gave us tea at the Central Club for Nurses, where we were addressed by Miss Maxwell of the Presbyterian Hospital and Miss Hilliard of Bellevue. Both of whom impressed us with the importance of our mission and with the idea that the honor and dignity of our profession and of our country depend largely upon us.

We are especially indebted to the clergy of St. Paul's chapel for the patriotic services for Army nurses they have so kindly provided for us. These include a most excellent course of conversational French lessons by Professor Bars and instruction in community singing under the direction of Dr. and Mrs. Reid.

The faculty of Fordham University also deserves our highest commendation and gratitude. Through the courtesy of Father Fortier, dean of the School of Sociology and the graduate school of Fordham, a large number of our nurses are given one hour's tuition in French daily, under the most excellent instruction of Madam Mulholland, wife of the Registrar of the University.

In conclusion, while we are all well, comfortable, and content, we eagerly await the order to embark on the little quartermaster tug, which will transport us to the ocean steamer en route for our duties in the Great War.

By Jean Haviland

"Are you going to Ellis Island?"

The outgoing ferry boat was due to leave her slip. Unmistakably, I was bound for Ellis Island, for the ship docked nowhere else, so why the question? I turned to look into a pair of pretty, intelligent brown eyes.

The rich brogue saved her from criticism and made a place for her in my heart while I made room for her beside me. We were both on our way due to report for Army nursing duty, having regularly sworn our allegiance to Uncle Sam and his service. Strange to say, we had been assigned to the same Base Hospital (the United States likes "colleens" too).

Our hesitation as to direction on leaving the ferry boat was relieved by a charming little lady from Missouri, who seized my heavy suitcase and went ahead to show the way.

I like Westerners, too, and my heart warmed to this one in her attractive uniform. It seemed she, too, was one of us, although having been sworn in and outfitted some days or weeks before, she was due to sail immediately, and I saw her only once again before she marched away in line to board the lighter,-so dignified and womanly and sweet they looked, that nursing contingent, passing, with measured tread, the middies standing at attention. At the same time, the other fellow's sister left to do "her bit" for him or them.

We were duly greeted, and our papers were examined in the office of the chief nurse. We realized how small a "bit" ours was when we knew we were only two out of hundreds constantly coming and going, with perhaps only time for equipment before sailing.

The dormitories were surprisingly spacious and airy, the food and dining service all that could be expected, perhaps more, and the general atmosphere of the place permeated by a spirit of cheer and helpfulness that must inevitably make for the broader outlook and the realization that we are all as one in this great strife, absolutely dominated by the desire to help where our remarkable capacity can best be used.

The wonderful system of outfitting crowds of nurses, ranging from "small thirty-two" to "large forty-four," seems perfect. We were soon arrayed in military garments, proud of the uniform, the Red Cross, and our glorious country.

We are severe and happy and hopeful; a little fearful, maybe, lest we may not match up with what Army duty requires of us, but we feel assured of the support and sympathy of our outstanding Chief Nurse, together with the positive recognition of our undivided efforts to put everything across in the way she expects as to.

We, too, are "sailing shortly" for duty "over there," and in our hearts is a warmth of feeling for Uncle Sam and his courteous and appreciative staff on Ellis Island that will remain with us for years and help to become valuable women in our country's service.

By Glenna Lindsley Bigelow

On February 21, 11 A. M., Unit No. — We received orders from Washington to proceed to Ellis Island for mobilization at once. So the sword has fallen at last upon our awaiting necks! After an excruciating half hour at the dentist's, I proceeded to the War Building for my immunity papers, which will prove to the world that I cannot catch anything on earth.

Fancy not being able to catch anything! What shall I do to evade a court-martial if I miss the last boat to the Island sometime? But I have not been to the Island yet. I had to ask the Sergeant how to get there, and he said: "Why, just find the Barge Office and go there."

I thanked him gratefully and set out for the B. 0. upon arriving, I was suddenly confronted by a very chic soldier-boy who presented arms right in my face. Luckily, I had convincing papers, for several people were looking on, and I should have disliked to have the affair a fiasco.

He let me pass, however, and whispered under his breath, like a ventriloquist, that it was a frigid day, and no one but I knew he was saying anything. I, then, sympathetically inquired, without opening my lips, how long he had to stay on duty, and he mumbled back, "Four o'clock, thank God !"

Several feet farther on, I became aware of a meek and lynx-eyed individual who asked in a velvet voice if I were a "Red Cross," to which I answered nimbly, "Yes," getting his meaning at once. He offered me a pass without further questioning.

He did not even ask where I was going or if I wanted to go there. I think he was very unsuspicious, for I had a little black bag in my hand and a pink kimono wrapped up in my muff, which, as usual, I could not pack in at the last moment.

The pass let me in through a narrow door to a narrow room. I cannot say that the people I found there had a happy aspect; in fact, they all looked somewhat strained and uncomfortable, and I wondered if it were the fault of the past, which, like mine, was unsolicited and signed for Heaven knows where; I had not even observed its direction. The only person who looked at all complacent was an Irishman who wandered around upside down with a clay pipe in his mouth.

A bell rang, a chain jangled, and we were herded upon a ferry boat bound for the "Isle of the Lotus Eaters," maybe, though I doubt it. Tomorrow, I will tell you if I arrived at a place that always could be remembered.

At 3.30 P. M. we made port and were led through corridors and corridors to the supreme head of affairs, from where I was finally conducted to the sleeping quarters of the nurses. These consisted of one large ward with twenty beds in it. Oh, what a feeling swept over me! Twenty empty beds! I felt as though twenty people had recently died in them.

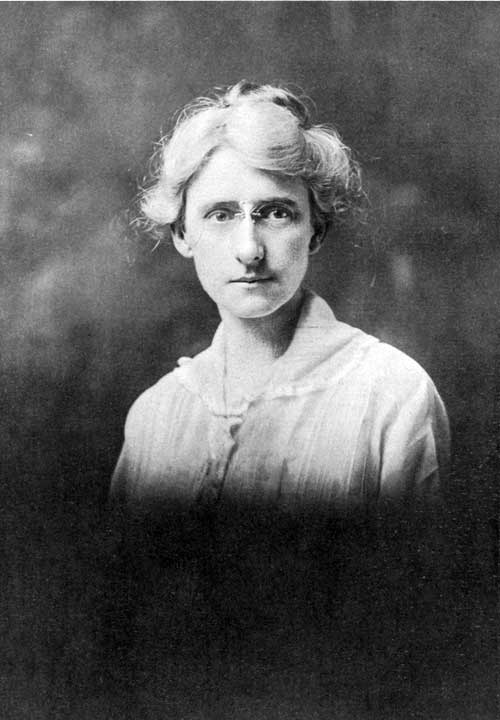

Dora E. Thompson, R.N., Superintendent Army Nurse Corps. Photo by Clinedinst Studio, Washington, D. C. American Journal of Nursing, May 1918. | GGA Image ID # 2194c1fe64

Uniform of Army Nurse Corps, Used Also by Reserve Nurses of the Red Cross. Photo by Joel Feder. American Journal of Nursing, May 1918. | GGA Image ID # 2194d71193

In the twinkling of an eye, or at least in a few hours, the whole aspect of the dormitory was changed. The twenty beds had twenty interesting proprietors, though we were all like probationers again, fearful of doing things we were not supposed to do. Our chief nurse's assistant came and detailed, in fluent phrases, the awful sins we could commit unwittingly. When she finished, I felt completely demoralized, as if there were a route all along the line.

At 5 p.m., we went to dinner after having crossed a viaduct and achieved a bewildering journey through a maze of corridors and blind alleys to Island No. 1.

Ellis Island, that "Isle of Tears," as it is called, that harbor for all undesirable humanity that floats in from foreign shores, is composed of three islands. We live in the contagious hospital on Island No. 3. But what of that? Nothing can infect our ardor, for we are en route to "over there" by a big ship that is spotted and striped from gunwale to funnel like a rearing zebra leaping out to sea.

February 22. It is odd to wake up in the morning, dragged from sleep by the thirty-eight enquiring eyes of one's roommates. After looking each other over, we spent a moment on the scenery.

The dormitory has all windows and is surrounded by water, except the staying end, which attaches us to the main building. It is like a ship at sea, but Dieu, Merci, is steady. We are as cozy and comfortable as possible here, with good beds, plenty of heat, and unlimited hot baths, and we like it. It is a desirable or preliminary experience for the first-line hospitals at the front, but we will want those, too. How well I know!

At 7 A. M., we turned out, put on all the clothes we could, for it was bitter cold, and walked an eighth of a mile to the dining room. For breakfast, there were fried eggs, apple sauce, potatoes, and coffee. Like the immortal Oliver Twist, I boldly asked for a second cup and was refused.

Roll call at 9 A. M., the dividing line between the attached and the irresponsible. We are Uncle Sam's nieces now and proud to tears to enroll in the ranks of his great Army. We are incomparably favored in the light of his kindly eye and in the strength of his high resolve.

On the ferry to New York this afternoon, we saw one of those camouflaged ships, which was painted in great waves of imagination from the very water's edge to the tip of the smokestack; I do not know what "Fritz" will think when he sees it, but it reminded me of a typhoon in the Indian Ocean, or whales' tails lashing the air.

Tuesday. Unit - went, en masse, to the tailor to be measured for uniforms. It was a wearying process to select, from three hundred identical costumes, one that would need the least altering for each figure. The fitters were very amiable until about lunchtime when one insisted that a particular coat was all right until his client (a Social Service nurse who had picked up some stray phrases in the Ghetto) spoke to him in Yiddish. Then he discovered it was all wrong and marked it up and down with his chalk.

A hurried lunch for us and then to the rubber man for Sou'westers. He was as pliable to every suggestion as his name implies until we did not know what we wanted. At last, however, we were rigged out with rubber coats and slickers that would fit us for any cod-liver oil advertisement.

Then off to Coward's for boots. Is it not terrible that the American nurses must go to war with Coward imprinted on their soles? But Flanders' mud may transform them and thank goodness, anyway, for paradoxes.

The boot store was uproar, and it took more than two hours to convince anybody that we knew where we were going and what we wanted to do regarding foot-covering. We did not know, so we took what was offered and straggled home in disorganized squads. Home? It is home to Ellis Island, the first stop en route to France.

Wednesday. There was no roll call this morning. That was not as important as a trip to Hoboken, where we all had to go for identification cards and fingerprints. I feel as if my "fate W. hung around my neck" surely now.

After this episode, we all filed into another small, stuffy room with a glaring electric light and a giant camera. A "fleisiger Berthe" (big Krupp gun) would not have been more formidable. However, each sat before the dreadful object while two dozen companions criticized her camera expression uncompromisingly. Then, "Smile and look at me," from the operator; click, and the thing was done. The picture dripping from its acid bath in precisely seven minutes was finished, developed, and printed. And as the Scotch woman said when she saw her first photograph, "It was a humblin' sight."

Shopping every day now for little things we did not realize we needed and eventually amounted to $50.00: a collapsible rubber basin, some hairpins, a novelty money bag, and a few ink tablets- how in the world can that amount to $50.00? But the money is gone, and we do not have the time to care.

The days in town are hectic, and one does not have time even to read the war news. This fact suddenly occurs to you one evening when you are hurrying to get the boat, so you run back a few paces to buy a paper and, incidentally, miss the 7.30 P. M. ferry to Ellis Island. The interim is three and one-half hours.

At 10.45 p.m., as you are seated patiently in the waiting room, somebody shouts that you will get the boat in the park (Battery Park). Perfectly convinced that the world has gone mad, you, however, follow the crowd into the garden and find that saucy "Immigrant" snugly moored up against the sea wall.

In a frantic attempt not to miss the cutter one night, one of the nurses accidentally put her foot into the void between the pier and the boat and narrowly escaped disaster. That did not distress her, however, for she was not afraid of drowning, but she might have lost her pass. That is the most terrifying thought here.

Miss Jorgensen, the chief nurse who has been so good to us, has profoundly impressed our minds with the crime of losing a pass, with the subsequent necessity of explaining it to Colonel K., who is commanding the port of embarkation.

Saturday night. The dormitory is the most amusing place in the evening when all the nurses return from town; their wares heaped high in their arms. It is a veritable Grand Street where all the coats and dresses are hung on the frames over the beds and bundles strewn all around. Articles are bought, sold, swapped, appraised, depreciated, and cornered.

Shylock would find some kindred spirits in the atmosphere of our little Rialto, and his glittering eyes would undoubtedly approve of our spirit of bargaining. By the way, we have a feminine Harry Lauder among us, whose Scotch burr caresses the ether with a subtle touch. She is the most optimistic of people, and when the conversation hovers about U-boats, her only concern is whether Providence or sticking plaster keeps the sailors' caps on their heads.

Some of us went over early to take the ferry this morning. We saw Unit - embark. It was a tremendously impressive sight; the sky was blue, and the sun shone brightly on the little procession of fifty nurses who looked dignified and stylish in their dark blue uniforms.

They emerged from their quarters, marched silently along the quay of Island No. 3, and over the bridge to the chapel on Island No. 1 when we lost sight of them momentarily. Soon, they came out of the building and marched, two by two, toward the little tender to take them out to their ship.

Their leader carried the flag, furled. That mass of color, crushed in her arms, made me tremble with emotion. It was like a tinge of blood, a dart of flame, an imprisoned thing seeking freedom.

It happened that a company of sailor boys, out for morning drill, was drawn up at "attention" right at the gangplank when the Unit embarked, which added tremendously to the impressiveness of the picture. But the silence was terrible; no fanfare of trumpets, no admiring friends, no flowers, only the grimness of parting. The little boat shrieked out a warning, warped away from the pier, and silently disappeared around the Island.

Friday. We received our equipment today. On the ferry, great packages and hundreds of boxes came over from New York. We stood up in line alphabetically to receive our consignment and marveled at the order and dispatch with which that great pile of things was dissipated.

Every person's name was on the correct box, in precisely the right place, so there was no confusion, and, presently, we found ourselves back in our dormitory, staggering under our load of gifts. It was like an individual Christmas tree, and we are immensely grateful. Too much praise cannot be given to the ladies of the Red Cross for their untiring work. I wish I could express how appreciative we are of all those kind people.

We realize the hard work involved and how monotonous the task of packing those kits must become after the novelty has worn off.

We, the nurses, indeed have the excitement, the change, and perhaps the danger while they are getting the dull end of the war, the stay-at-home part, which is always the hardest. We bless them, everyone, for these unnumbered comforts that will smooth our way "over there."

The British War Office published some interesting facts about its industrial operations. Reels of cloth and flannel would go seven times worldwide at the equator. The War Office turned out 250,000,000 yards of material a year.

About 1800 tons of crude glycerine, extracted from the waste food of the Army, has been sold to the Ministry of Munitions at £59 a ton, about $295.00. Under the old system, the tin for jam rations alone required as much steel every month as would build a 300-ton ship; using a wood-pulp board saves 60,000 tons of steel a year. Two hundred seventy million meat rations were sent to the Army last year, and 84,000,000 pounds of tea.

Graham, Flora A., Jean Haviland, and Glenna Lindsley Bigelow, "Ellis Island from Three Points of View," in The American Journal of Nursing, Vol 18, No. 8, May 1918, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, pp. 613-622

Key Highlights and Engaging Content

The Personal Narratives:

The article is divided into three distinct perspectives from women in the Army Nurse Corps: Flora A. Graham, Jean Haviland, and Glenna Lindsley Bigelow. Their stories offer a personal, emotional look at Ellis Island during wartime.

Each of them recounts different aspects of their journey, from the first ferry rides to life in dormitories on the island. Their reflections capture the uncertainty and anticipation of nurses heading off to serve in World War I—offering a relatable human touch amidst the historical facts.

📸 Noteworthy Images:

📌 Ellis Island Dock with Immigrants in Background circa 1915: This photograph, showing immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, perfectly complements the article's narrative of people passing through Ellis Island during the early 20th century. It symbolizes the gateway to America while also highlighting the flux of individuals during this period, which is central to the article’s theme.

📌 Uniform of Army Nurse Corps, Used Also by Reserve Nurses of the Red Cross: This image not only connects the article to the military mobilization at Ellis Island but also serves as a powerful reminder of the contribution of women during the war. The Army Nurse Corps uniform represented the nurses' essential role in wartime and symbolized their commitment to service.

Ellis Island as a Hub of Mobilization:

The piece describes the role of Ellis Island as a central hub for the mobilization of Army nurses. It contrasts the military organization of the island with the human side of immigration:

Red Cross activities, training in French for nurses, and patriotic services are highlighted as ways that Ellis Island balanced practical wartime duties with maintaining a sense of camaraderie and morale.

This dual purpose of military preparation and immigrant inspection showcases Ellis Island's unique position in American history.

The Social Environment:

The three nurses describe their experiences within the social fabric of Ellis Island, from the nurse dormitories and meals to the constant movement and interactions with other nurses and military staff. Their narrative conveys a sense of solidarity and purpose.

Notably, the humorous shopping stories and the bargaining for uniforms and personal items provide a lighthearted counterpoint to the otherwise serious tone, making the article both relatable and engaging for modern readers.

Immigration and Military Service:

An undercurrent in this piece is the intersection of immigration and military service. While Ellis Island is historically known for its immigration processing, the focus here is on its role in preparing nurses who were part of the wartime mobilization effort.

The nurses’ journey from Ellis Island to Europe highlights their pivotal role in supporting American soldiers abroad, an often-overlooked aspect of immigration history.

Educational and Historical Insights

This article provides a unique historical insight into how Ellis Island served as a military mobilization station during World War I. It reveals how wartime demands transformed the island from a primary point of entry for immigrants to a crucial military service station.

Teachers and historians will find it valuable for understanding how war-time patriotism and immigration intersected, and how Ellis Island remained an active point of transition, even as immigrant families continued to pass through its gates.

For genealogists, the article's descriptions of nurses arriving at Ellis Island in 1918 could offer new avenues for exploring family history, especially if their ancestors were involved in the medical efforts during World War I.

The personal anecdotes also add depth to the understanding of how immigrants and nurses adapted to new environments and responsibilities during this era.

Final Thoughts

Ellis Island from Three Points of View not only adds a personal dimension to the historical understanding of Ellis Island but also paints a vivid picture of the immigrant experience during World War I.

The personal stories of these nurses, while focusing on military mobilization, also touch on the broader humanity of the immigration process—highlighting adapting to a new land, serving a greater cause, and the daily grind of service and sacrifice.

The article is a rich resource for anyone studying immigration history, military contributions, or gender roles during wartime.

🔎 Research & Essay Writing Using GG Archives

📢 This is NOT a blog! Instead, students and researchers are encouraged to use the GG Archives materials for academic and historical research.

🔎 Looking for primary sources on Titanic’s lifeboat disaster? GG Archives provides one of the most comprehensive visual collections available today.