📖 Rural America in Crisis: The WPA's Study of Families on Relief During the Great Depression

📜 Explore the 1938 WPA study on rural families affected by the Great Depression. This report provides invaluable insights into economic hardship, relief programs, and the struggles of farmers, sharecroppers, and laborers across America. Essential reading for teachers, historians, and genealogists!

Front Cover, Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152ca6c06a

📜: Rural Families on Relief - Research Monograph XVII (1938)

📖 "Struggling to Survive: How Rural Families Navigated the Great Depression with WPA Relief"

The Great Depression brought unprecedented economic hardship to rural communities, leaving countless farm families, tenant workers, and agricultural laborers struggling to survive. This 1938 WPA Research Monograph XVII, titled Rural Families on Relief, presents an in-depth sociological and economic study of the conditions, challenges, and relief efforts affecting rural America during the 1930s.

For teachers, students, genealogists, and historians, this report is a goldmine of historical data, offering critical insights into:

✅ The impact of economic cycles, drought, and resource depletion on rural families.

✅ How government relief programs shaped rural employment, mobility, and living standards.

✅ The shifting demographics, education levels, and social structures of affected communities.

✅ The different types of rural families—from farm owners to sharecroppers to migratory laborers.

This comprehensive analysis, conducted by Harvard University scholars and WPA social researchers, provides an objective look at the harsh realities faced by rural Americans while highlighting the role of relief efforts in stabilizing these struggling populations.

Letter of Transmittal, Corrington Gill and Col. F. C. Harrington of the Works Progress Administration, 27 December 1938. Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152caf457a

Letter of Transmittal

Works Progress Administration, Washington, D. C., December 27, 1938.

Sir: I have the honor of transmitting an analysis of the social characteristics of rural families receiving assistance under the general relief program.

The report evaluates the various characteristics of rural families on relief in terms of their effect on the families' need for aid. The findings of this analysis will be of distinct value to relief administrators in rural areas. At the same time, it contributes to the general study of rural families in lower-income groups.

Not only are rural relief families found to differ in their characteristics according to their position in the local rural community, but even wider differences exist among the various geographical areas of the country.

The predominant industries determine the extent to which the head of a family will be able to continuously care for his dependents, and the cultural traditions largely determine the composition and solidarity of the family unit.

Four factors are of particular importance in determining the incidence and amount of relief for rural families:

- The number of employable members in the family and their capabilities;

- Unemployment because of the business cycle;

- Unemployment and underemployment because of the weather cycle; and

- Social action is needed to improve the standard of living.

The study was made in the Division of Social Research under the direction of Howard B. Myers, Director of the Division. The data were collected under the supervision of A. R. Mangus and T. C. McCormick. Acknowledgment is made of the cooperation of the State Supervisors and Assistant State Supervisors of Rural Research, who were in direct charge of the fieldwork. The analysis of the data was made under the supervision of T. J. Woofter, Jr., Coordinator of Rural Research.

The report was prepared by Carlo C. Zimmerman of Harvard University and Nathan L. Whetten of Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station, with the assistance of Wendell H. Bash of Harvard University. Ellen Winston of the Division of Social Research edited it.

Respectfully submitted.

Corrington Gill, Assistant Administrator

Col. F. C. Harrington, Works Progress Administrator.

Summary

Rural Families in the United States were subjected to several unusual forces during 1930-1935, which resulted in severe economic distress in all sections. This distress was a statistic and a harsh reality that these families had to endure. Some regions suffered directly from only one force or received the diffuse effects of several. In other regions, the full brunt of various forces is focused on the area. It resulted in the almost complete collapse of normal economic and social activities, a situation that demands our empathy and understanding.

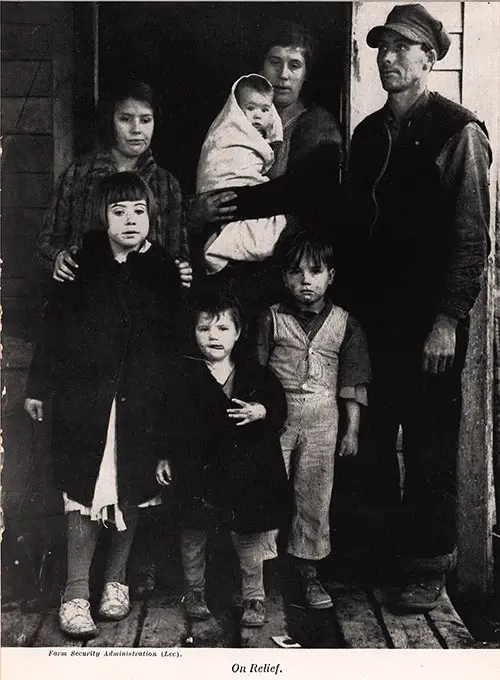

Rural Family on Relief. Photograph by Farm Security Administration (Lee). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152cd9ec1f

While long-range factors essentially caused rural distress, the effects of the business depression were nevertheless of great importance in the rural relief situation. The drop in the price of farm commodities because of cyclical fluctuations in the money market was only one factor in this situation, as it affected the farmer and the village dweller.

Price movements resulting from the weather, crop conditions in foreign countries, and the long-term trend in agricultural production and exportation were also included. Thus, the farm price movements resulted in declining prices and sales. This included both the drop in value and quantity of exported goods and the change in the urban market with the depression.

Another force bearing on the rural population and helping to determine relief needs, which can also be identified with the business depression, was the change in nonagricultural work opportunities, which accompanied the decline in industry and commerce.

This affected primarily the large numbers of part-time farmers who live in densely settled and relatively urbanized areas. These families were forced to become more dependent on the soil and to develop a more self-sufficient farm economy.

The decline in the utilization of natural resources has been partly connected with the business depression and partly dependent upon a long-term trend. Activity in isolated coal and iron mining areas has decreased or stopped entirely, and the lumber industry has been sharply curtailed. These are typical examples of industries that provide employment to rural families on a part-time or full-time basis.

In some areas, the depression coincided approximately with the exhaustion of natural resources, so the shutdown has been permanent rather than temporary. For the most part, rural families suffering under the pressure of these forces are located in mountain and wooded areas.

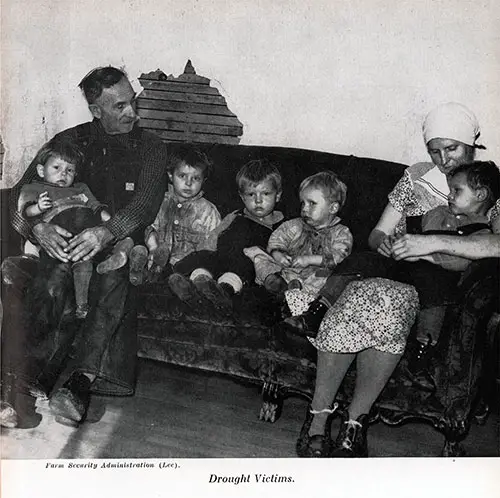

A factor not connected with the business depression was the drought. Short-time cyclical movements of rainfall and dry weather have not been unusual on the plains of the great West. Still, in 1934 and 1936, some droughts were unequaled for both extensity and severity during this generation.

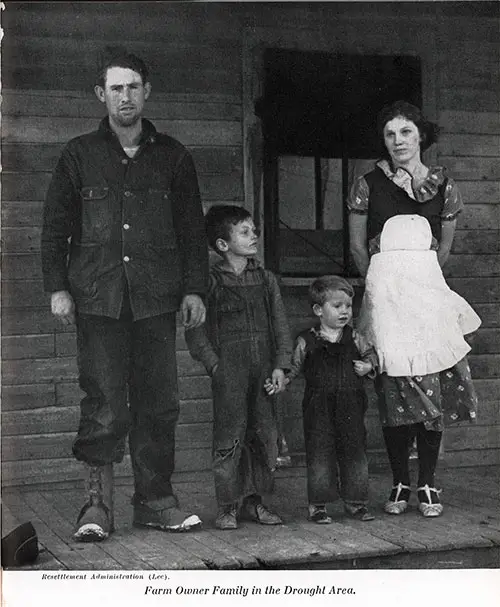

Farm Owner Family in the Drought Area. Photograph by Resettlement Administration (Lee). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152d3bdec3

The most extreme effects of the drought were found in a belt running north and south through the two Wheat Areas and bordering both the Com Belt and Western Cotton Areas. Still, minor effects of the drought wore found in almost every section of the country.

Types of Farm Families

Aside from their regional incidence, the forces leading to the need for assistance were found to affect rural families in different ways and degrees according to the type of farming they engaged in. Commercial farmers may be accurately described as small-scale entrepreneurs.

All of their efforts are concentrated on the production of cash crops, generally only one, and they usually grow comparatively little for home use. They live under relatively the same type of money economy as city people, and their prosperity is determined by the price of these goods in the market.

It is also significant that the price of most of the products included in this type of production is largely determined by the exported surplus. Since they are goods of relatively inelastic demand and subject to wide fluctuations in supply, such products, at times, undergo violent price fluctuations in accordance with weather and economic conditions.

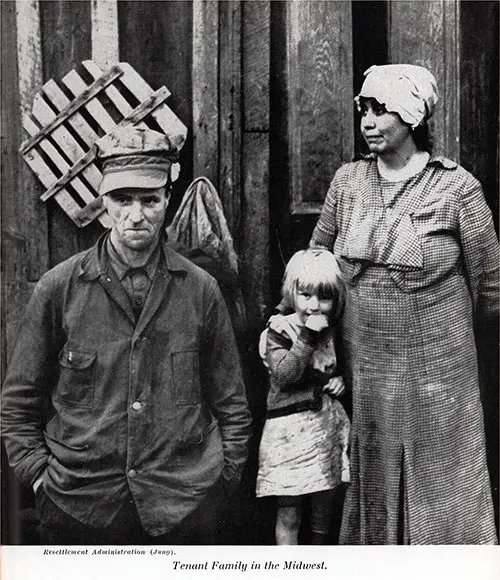

Tenant Family in the Midwest. Photograph by Resettlement Administration (Jung). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152db20388

Consequently, the business depression and the decline in the exportation of foreign products have been the most important factors in every area affecting the relief needs of commercial farmers. One governmental action that has ameliorated conditions for these farmers has been the agricultural adjustment program. As a result, relief needs have not been as extensive for these farmers as they otherwise would have been.

A second category of farm families may be called noncommercial. It consists mainly of those families which combine part-time farming for homo consumption with part-time industrial or commercial work and those which lead a relatively self-sufficing life in the more isolated areas.

For these families, the most important influence has been the decline in industry in isolated areas, together with the depletion of natural resources. This also includes the decline in employment in and around cities. These families are influenced to a certain extent, however, by the decline in the agricultural market since they sell their surplus for cash. These families are helped relatively little by agricultural price-raising.

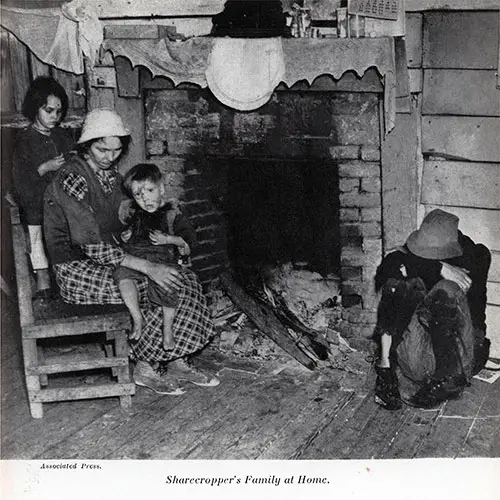

Cutting across both the commercial and noncommercial groups, a third category of the agricultural population may be called the chronically poverty-stricken. This chiefly includes farm laborers in all areas and the sharecroppers and tenants of the cotton areas. These agricultural groups work for commercial farmers and seldom produce much food for homo consumption.

They are directly affected by the prosperity of the farmers who hire them, so their prosperity and depression are concurrent with those of commercial producers. Moreover, it is safe to say that in the current situation, the troubles of commercial farmers have been passed on to these groups and accentuated in the process.

Analysis of Rural Relief Families by Area

Although the diversity of occupations and the different types of families within occupations have been repeatedly pointed out, there is still a tendency to think of the rural population as a homogeneous unit.

Since rural was defined for purposes of this study as including open country and villages of less than 2,600 inhabitants, nearly all classes and occupations were included in one way or another.

The rural relief families differed not only in their characteristics according to their position in the local rural community but also in even wider differences among the various geographical areas of the country. Significant differences in the average family on relief in June 1935 were found, for example, between the Eastern Cotton and Spring Wheat Areas.

Sharecropper's Family at Home. Photograph by the Associated Press. Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152dc87b5a

In addition, it was found that, when classified on the basis of type of farming area, relatively homogeneous groups in the rural population were established, even if all the occupations were included. Consequently, the average family in different sections of the country was studied using a regional analysis, resulting in a better understanding of the peculiar problems in each section.

In the Eastern Cotton Area, more relief families were engaged in agriculture than the country's average. However, the proportion was still less than 50 percent. Despite the area's comparatively slight urbanization, agriculture and family solidarity still set the prevailing tone.

The relative multiplicity of social classes within agriculture, including owners, tenants, croppers, and laborers, determines a more pronounced social stratification than in other agricultural areas.

The relatively small size of the average relief family (3.7 persons) was due partly to the splitting of plantation families and partly to the fact that the median age (43.7 years) of the head of the family was less than for many other areas. Dependent family members were found in about the same proportions as in the country as a whole, but there were more broken families.

Excessively high mobility within short distances and a low level of formal education are two factors leading to an unusually low material standard of living. Considering all factors, however, this area has preserved its social vitality to a greater extent than many of the wealthier sections.

In the Western Cotton Area, more of the relief families (54.3 percent) were customarily engaged in agriculture. The average family was a little larger than in the Eastern Cotton Area (3.8 persons) but still smaller than the country's average.

The splitting of plantation families was probably more widely practiced here than in the older and more traditional East, and here, too, the heads of families were relatively young (41.7 years of age). Slightly more of these families were normal families consisting of husband and wife or husband, wife, and children than in the Eastern Cotton Area.

Lunch Time for Cotton Pickers. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Lange). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152dd588b1

Although they had more dependents, this did not result in an unduly higher birth rate. Material standards are slightly higher in the Western Cotton Area. Still, the improvement in material levels has meant a regression or at least no advance in the stability and vitality of social relations.

The Appalachian Ozarks are the best example of self-sufficing farm family living. Four out of ten of the heads of rural relief families were customarily employed in agriculture. Here, the average family was the largest (4.3 persons) of any area, with the exception of the Spring Wheat Area.

The fertility of the rural relief population was the highest of any of the areas surveyed. Although families in this area frequently have a meager existence, a minimum living is assured to them as long as they remain on the land. The chief function of this area continues to be the production of new workers for the cities.

The Corn Belt is a relatively prosperous and highly commercialized area. Here, corn is produced either for direct sale or for livestock feeding. Commercial production is dominant, and agriculture is on a relatively large scale. The average head of a rural relief family was 43.5 years of age, and 4 out of 10 heads were engaged in agriculture.

The tendency toward a small family system is evident, and although there was a high proportion of normal families, the fertility rate was below the average. In this area, farm families as a whole have achieved a level of living seldom paralleled in agricultural history, but the social system does not give great evidence of stability, and the farm family is not maintaining its strength and vitality.

The Hay and Dairy Area cuts through some of the country's most highly urbanized sections. It forms a belt from the Atlantic seaboard to the fertile lands of Wisconsin, supplying dairy and other products demanded by the highly industrialized and commercialized culture of that section of the country.

Only a small proportion of agriculturalists (28.9 percent) were found among the relief families in this area. The median family was about the same size as the country's average, but the head was about 2 years older on average. Although 76.0 percent of the rural relief families were normal, the birth rate was lower than for all areas surveyed.

Since most workers earn their living in nonagricultural occupations and farmers are directly dependent upon the prosperity of the urban market for the sale of their products, the problems of this area are essentially the same as or are ultimately tied up with, those of the contiguous cities.

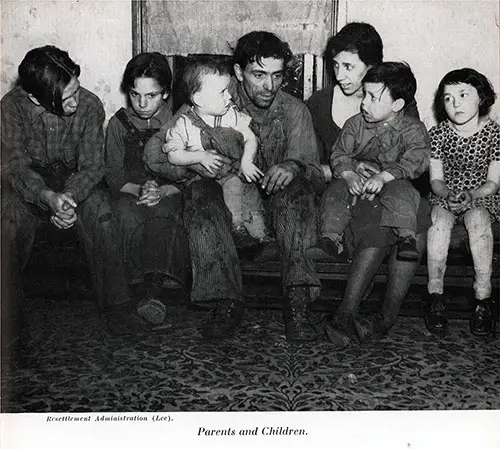

The Lake States Cut-Over Area consists of isolated farming sections and mining communities. Only 26.0 percent of the heads of rural relief families were agriculturalists, and the problems in this area are in many ways different from those in the neighboring Hay and Dairy Area.

Parents and Children. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Lee). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152e271ab0

Its recent settlement, relative cultural heterogeneity, isolation, and depletion of natural resources all help determine its extremely high relief rate, meager standard of living, and unstable culture.

Although the two Wheat Areas differ, they share many similarities with other agricultural areas. A higher proportion of the families are engaged in agriculture than in other areas, with the exception of the Western Cotton Area, and most of this agriculture is extensive and commercial.

Like the Corn Belt, the Wheat Areas have had periods of great material prosperity; educational standards are advanced, and material comforts are highly valued. However, the comparatively recent settlement and development of the Wheat Areas, the ethnic heterogeneity, the high rates of social mobility, and the wide fluctuations in climatic conditions all led to a social instability that markedly affected relief rates. '

The Ranching Area is but a step removed from the Wheat Areas in terms of its extensive agricultural production. However, mining and lumbering occupations raise the proportion of nonagricultural workers and help account for the large proportion of nonfamily groups in the rural relief population.

This area presents problems that differ from those in other places in many respects. Still, these differences in family statistics are likely influenced particularly by factors associated with an area of new settlement.

The New England Area further intensifies the factors found in the Hay and Dairy Area. Urbanization has continued, and the rural culture is even more highly commercialized and industrialized.

Only one out of eight rural relief families in this area in June 1935 was engaged in agriculture, and the proportion of nonagricultural families in the relief population was higher than in any other area surveyed. This is due both to the large number of local rural industries and to the large number of city workers living in the surrounding countryside.

Occupational Origin of the Heads of Rural Relief Families

Agricultural occupations accounted for about the same proportion of the heads of rural relief families in Dune 1935 as did nonagricultural occupations, 40.6 percent compared with 41.2 percent.

Considering that relief represented only one of four public measures to assist agriculture, it is disheartening that so many farm families had to have this form of assistance. The proportion of agriculturalists among the heads of rural relief families varied from more than two out of three in the Spring Wheat Area to one out of eight in New England.

Among the agriculturalists, there were over twice as many farm operators as farm laborer families on relief. This is not surprising since there are considerably more than twice as many farm operators as hired farm laborers in the United States.

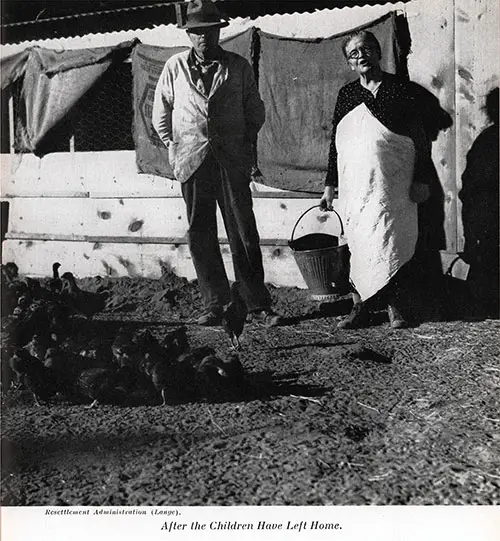

After the Children Have Left Home. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Lange). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152e46a3b9

Within the farm operator group, however, tenant families constituted a greater proportion of the relief cases than did farm owner families, although the country as a whole has about three farm owners for every two tenants.

Unskilled laborers accounted for by far the largest proportion of the heads of nonagricultural families. In New England, there were also a large number of relief families whose heads were skilled and semiskilled workers.

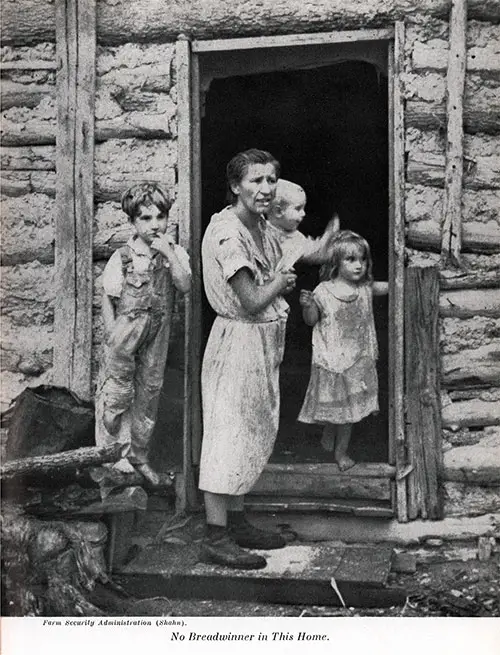

Families whose heads were nonworkers accounted for 15.6 percent of all relief cases, reflecting the tendency for relief rolls to include a large number of families that, for various reasons, do not have a breadwinner. In 2.5 percent of the cases, the head of the family had no usual occupation.

Personal Characteristics of the Heads of Rural Relief Families

The average head of a rural relief family was in the prime of life, the early forties. Village heads, on the whole, were about 2 years older than those in the open country. The heads of families in New England had the highest average age (46.6 years), while the lowest average age was found in the Winter Wheat Area (39.0 years).

The median age of heads of agricultural families on relief was about the same as that of heads of nonagricultural families. Farm owners, however, had the highest average age of any occupational group on relief (46.5 years).

On the other hand, farm laborers were the youngest group, averaging only 36.4 years. Among the nonagricultural people, skilled laborers, with an average age of 43.7 years, had the highest overage of any subgroup.

Negro family heads, on relief, were much older than white heads on average. The difference in the Eastern Cotton Area was 4.9 years, and in the Western Cotton Area, 7.5 years.

The western areas of extensive, commercialized agriculture had the smallest proportions of rural relief families with female heads, while the southern regions, including the Eastern and Western Cotton and the Appalachian-Ozark Areas, had the highest proportions.

An exception to this rule was found in the Ranching Area, which ranked with the South in the proportion of families with female heads. Significant differences also existed between village and open country residents in that almost half as many village heads of rural relief families were women, as was the case among open country heads.

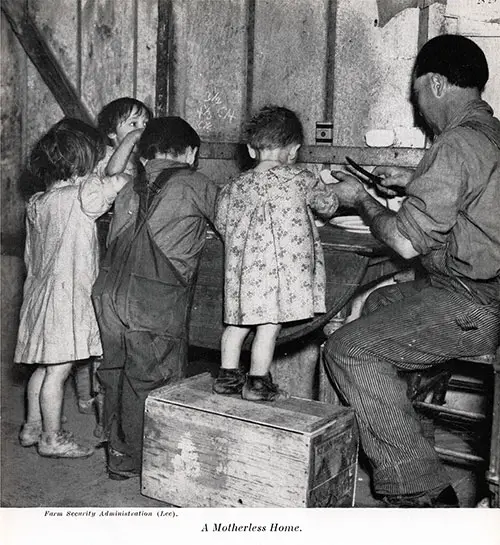

A Motherless Home. Photograph by the Farm Security Administration (Lee). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152e4bf8c5

Most of the male heads of relief families were married. In contrast, most of the female heads were either unmarried or had had their homes broken by divorce, separation, or death. For all areas, the highest proportion of female heads married was 15.7 percent for the age group 45-64, while the lowest proportion was 0.6 percent for those aged 65 years and over.

In contrast, the highest proportion of male heads married was 90.9 percent in the 25-34 age group, and the lowest was 61.5 percent in the 65-year-old group. The proportion of family heads who were married was greater in the open country than in the villages, while the proportion of widowed, divorced, or separated heads tended to be greater in the villages.

Differences in marital conditions among the areas were consistent with differences in social and economic backgrounds. The greater industrialization of New England and the North has led to women's greater participation in industry. Consequently, the emancipation of women has reached its most advanced stages in these regions.

Accompanying this emancipation is a rapidly rising divorce rate and a general disintegration of former social rules regulating the distribution of rights and duties of the sexes.

Size and Composition of Rural Relief Families

The problem of the size and composition of relief families is vital to relief programs from many points of view, but principally because large families, or those with numerous dependents and few gainfully employed or employable, may need relief more frequently and in more significant amounts than smaller families or those with relatively more productive units.

The median size of the rural relief family in June 1935 was 3.9 members. The open country families were larger than those in the villages. Averages, however, do not give an adequate picture of the situation with respect to family size. Of all the rural households receiving relief in June 1935, 9.9 percent were one-person households.

This was a 2 percent greater proportion of one-person households than was found for the whole rural United States in the 1930 Census (7.7 percent). Since severe economic depressions usually increase social solidarity, at least for a while, these data suggest that the proportion of one-person households receiving relief was much greater than expected from a normal rural population sample.

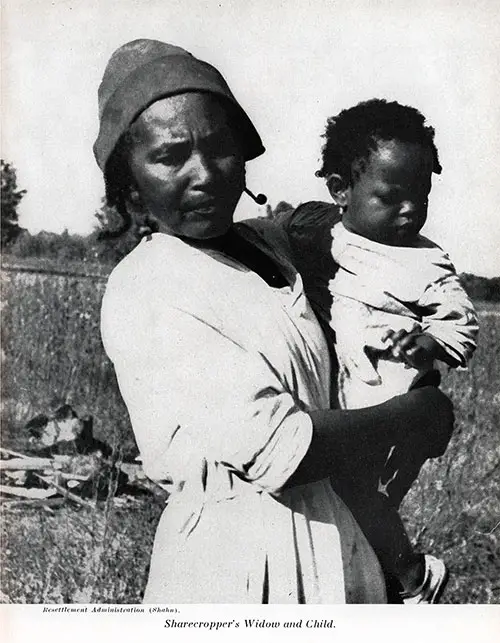

Sharecropper's Widow and Child. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Shahn). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152e90f9fd

Further comparisons with census data suggest that a larger proportion of rural relief families comprised six persons or more. In contrast, a larger proportion of families in the general population consisted of two or three members. Families with four or five members were found in about equal proportions among both relief families and families in the general population.

Rural relief families had relatively more young members (children under 16 years of age) than are found in the general rural population, and they contained a smaller proportion of working-age adults.

Dependent Age Groups

Four out of five rural relief families contained persons in the dependent age groups, i.e., persons under 16 or 65 years of age and over. Three out of five relief families had children under 16 years of age but no one over 64 years; one-eighth of the families had individuals 65 years of age and over but no children under 16; while one out of twenty families contained children and aged persons. These proportions varied somewhat among the agricultural areas of the country. They were related to the type of economy and the "age" of the area.

In general, many dependents in a family may indicate a prolific population, where a high birth rate results in large families, or it may indicate a high degree of family solidarity. Again, there is the possibility, as shown in the Cotton Areas, that families may be split so as to relieve aged persons and leave the younger employable people to fend for themselves without the responsibility for other individuals.

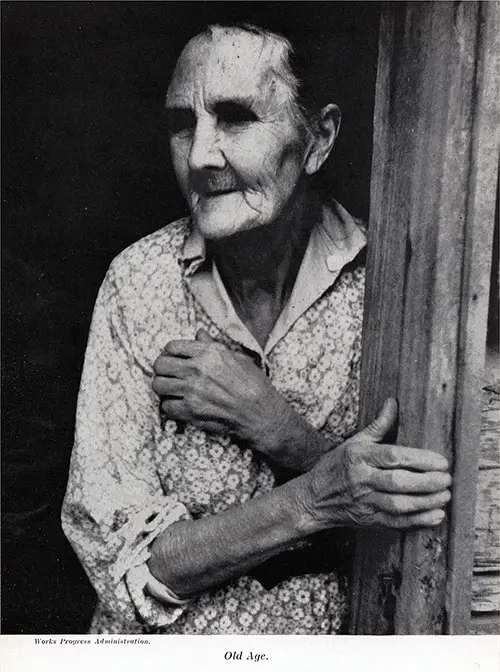

Old Age -- An Elderly Woman. Photograph by the Works Progress Administration. Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152e9d25bd

All of these factors may operate to increase the number of old or young dependents on relief. The question of dependency and relief is, however, related principally to the fundamental economic and cultural factors in any particular region.

The predominant industries and occupations determine the extent to which the head of a family will be able to care for his dependents continuously, and cultural traditions, to a large extent, determine the internal solidarity and cohesiveness of the family unit.

Background factors of an economic, sociological, or even medical nature, when viewed in their full complexity, are agents that determine the number of dependents on relief. Families in the South, including the Appalachian-Ozark Area, for example, are likely to be large because of high birth rates; they tend to cling together in a cohesive aggregate.

Loss of economic support, or the injury or death of the chief provider, quickly forces the whole aggregation on relief. Therefore, it is easy to understand why the proportion of families with no persons in the dependent age groups should be smallest in the South, where rural cultural traditions are strong and greatest in the North, where the strong Yankee traditions are now nearly submerged by the newer mores of an industrialized and urbanized society.

Family Structural Types

For purposes of analysis, family units were divided into three main types: normal families, broken families, and nonfamily types. Seventy-two percent of all rural relief families were in the normal group, while 10.9 percent were broken families and 16.6 percent were nonfamily types.

Most normal families consisted of husband and wife or parents and children alone, while about one out of nine also had relatives or friends present. Normal families were relatively more frequent in the open country than in the villages, and a larger proportion in the open country consisted of husband, wife, and children, as compared with husband and wife only in the villages.

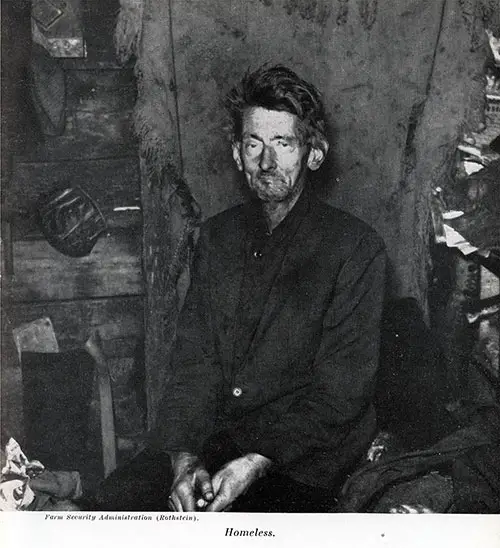

Homeless Man. Photograph from the Farm Security Administration (Rothstein). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152ea26ace

Likewise, there were more broken families in the villages than in the open country, and broken families with female heads especially tended to congregate in the villages. Normal families were relatively more prevalent among the agricultural (82.2 percent) than nonagricultural (77.4 percent).

Broken families occurred most frequently in the southern areas. Nonfamily types were most evident among the Negroes of the South and in the industrial and urban areas of the North and East.

Fertility of Rural Relief Families

The relationship between fertility and relief is difficult to measure. The relief data were compared with the 1930 Census data for identical counties, and certain relationships were noted concerning the number of children under 5 years of age per 1,000 women 20 to 44 years of age in the population.

However, the comparison is subject to qualification on several scores. One difficulty is that the census figures and the relief figures differed by 5 years, and the depression of the early thirties had far-reaching effects on marriage and birth rates.

Another was that relief practices in certain areas, particularly in the Western Cotton Area, split tenant and cropper families and placed aged or unemployable members on relief while the younger and more able members were kept under the landlord's care.

This would naturally tend to affect the size of the relief family. From the available data, however, it appears that for the country as a whole, the fertility ratio for the relief families was considerably higher than that for the general population.

Penniless and Alone. Photograph by Farm Security Administration (Rothstein). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152eac3b27

This is to be expected since relief families mostly come from the lower social and economic strata, where the birth rates are higher than those in the higher strata. Furthermore, since population traits are well grounded in the mores, relief families with more children may continue, at least for a time, to have children while still on relief.

However, the relationship between fertility and relief was by no means uniform. In some areas, fertility was much higher among relief families than census families, particularly in the Appalachian- Ozark and Ranching Areas.

In other areas, the differences were smaller, while in the Eastern Cotton Area, the number of children under 5 years of age per 1,000 women aged 20 to 44 was actually slightly smaller for the relief families than for all families in 1930.

Employability, Employment, and Amount of Relief

Employability and employment are directly related to relief and are vital factors in family status in either prosperity or depression. A family's employability composition sets the outside limits for its employment success, and many families are greatly handicapped by the lack of capable members between the ages of 16 and 64.

No Breadwinner in This Home. Photograph by Farm Security Administration (Shahn). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152f3cf616

The plight of many rural relief families can be shown by the fact that one-eighth of them had no employable worker, and an additional 7.8 percent of these families had female workers only. These two types of unemployability were relatively most important in the two Cotton Areas. Unemployability was exceptionally high among the Negroes of the South and relatively lower among the whites.

During the Depression, work in agriculture was relatively more stable than in nonagricultural. However, the past unusual agricultural production period forced many normally self-supporting agricultural families to rely on relief. However, only 29.2 percent of the gainful workers who had usually been employed in agriculture were unemployed at the time of the survey, contrasting with 72.1 percent of the nonagricultural workers.

The small proportion of unemployed in agriculture, however, was partly because farm operators were arbitrarily defined as employed if they were still on their farms, even if they had no cash income. For the groups employed within these broad classes, much more occupational shifting occurred among nonagricultural occupations.

Drought Victims. Photograph by the Farm Security Administration (Lee). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152ff6b4ce

Only 1 percent of the former agricultural workers had shifted into nonagricultural jobs, but almost 11 percent of the nonagricultural workers were employed in agriculture at the time of the survey.

This difference was also shown by the fact that 95.8 percent of all the employed workers in agriculture were engaged in their usual occupations, as contrasted with 55.7 percent of the workers in nonagricultural occupations. In part, this reflects a widespread movement to the farm during the Depression, and it also represents a reversed current of occupational mobility, which caused a general shift down the scale for workers at all levels.

Specific trends were observable when rural relief families were analyzed according to the continuity of their relief histories. Of all cases on relief in June 1935, 74.3 percent had received assistance continuously since February.

Another 14.2 percent of the cases had been reopened between March and June, and only 11.5 percent were new cases. Slightly more new cases appeared in the villages than in the open country.

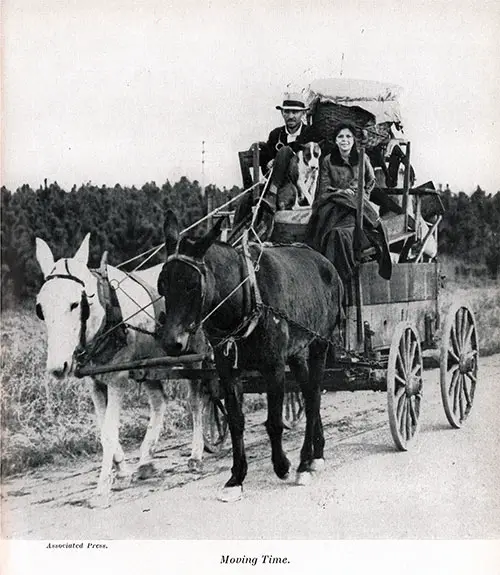

Moving Time. Photograph by the Associated Press. Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 15301c050f

Continuous relief histories were found most frequently among groups of a generally low economic level or those significantly affected during the depression period by unusual circumstances. The Negroes in the South are an example of the first type, and the farmers in the drought area are an example of the second type.

The average amount of relief per family was influenced mainly by these factors, such as low economic levels or unusual stress conditions. Also important in determining the amount of relief were comparative price levels and living costs. The lowest amounts of relief were found in the three southern areas, particularly among the Negroes, and the highest amounts were spent in the industrialized regions of the North and East.

Indeed, the cost of relief per family in the Eastern and Western Cotton Areas was not more than one-third the cost in New England. Four factors were most important in determining the incidence and amount of relief for rural families: (1) The number of employable in the family and their capabilities; (2) unemployment because of the business cycle ; (3) unemployment and underemployment because of the weather cycle; and (4) social action for improving the standard of living.

Mobility of Rural Relief Families

Only crude measures of the mobility of rural relief families were available. For the most part, the families were divided into three groups as follows: lifelong residents, referring to those families whose head was born in the county in which he was living at the time of the survey; pre-depression migrants, referring to those families whose head moved to the county at any time before 1930; and depression migrants, including those families whose head moved to the county sometime during the period 1930 to Juno 1935.

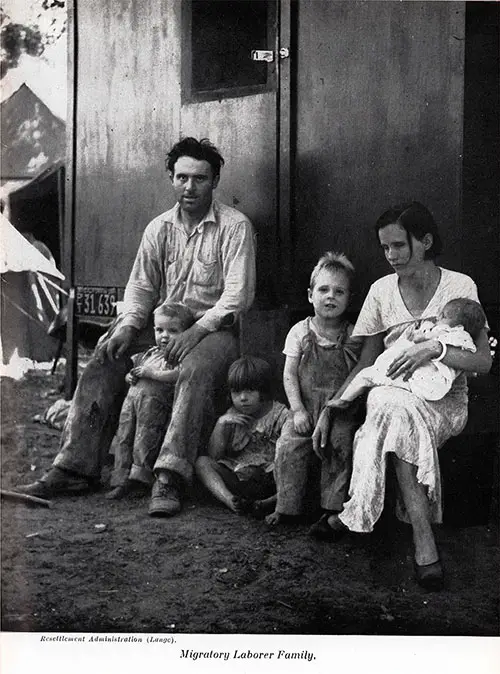

Migratory Laborer Family. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Lange). Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 1530632a27

Of the heads of rural families on relief in Juno, 1935,40.5 percent were lifelong county residents; 45.6 percent had moved to the county before the Depression; and the remaining 13.9 percent were depression migrants. As might be expected, smaller proportions of the heads of rural relief families were lifelong residents in the more recently tied areas than in the areas of older settlements.

The proportion of lifelong residents was 14.4 percent in the Winter Wheat Area, 17.8 percent in the Lake States Cut-Over Area, 22.4 percent in the Ranching Area, and 28.0 percent in the Spring Wheat Area. All of these are areas of comparatively recent settlement. Portions of the two Wheat Areas and the Lake States Cut-Over Area were settled as recently as the World War.

More lifelong residents were reported in the South and other sections of older settlements. Migration during the Depression was characterized by two main types. The first was migration because of the drought.

This was most noticeable in the wheat and western cotton areas, resulting in a shifting population within those areas and a movement to the villages and states in the far west. The second form of depression migration was the back-to-the-farm movement from the depression-stricken cities. This was important in the self-sufficing areas of the Northeast and also of great importance in the mountain areas of the South.

Agriculture is an occupation that encourages stability, as contrasted with nonagricultural occupations. Within agriculture, farm operators were more stable than farm laborers, but among the nonagricultural occupations, unskilled laborers were the most stable group.

More nonagricultural workers than agricultural workers moved during the Depression. For farm operators, the Depression meant moving to the village and for nonagricultural workers to the country. In contrast, many farm laborers moved to another location in the open country.

Education of Rural Relief Families

Teaching Aunt Nancy to Read. Photograph by the Works Progress Administration. Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 1530aff6cb

Heads of rural relief families were on a comparatively low educational level since less than 4 percent were high school graduates, and only about 35 percent had completed as much as a grammar school education.

Vast differences appeared among the various areas, however, as well as between village and open country residents, between agricultural and nonagricultural workers, and between whites and Negroes. In general, the educational level was higher in the more industrialized and urbanized areas than in the more agricultural areas.

Similarly, within each area, the agricultural workers had a lower educational level than the nonagricultural workers. In every area, a larger proportion of the heads of village families had completed a grammar school education than the heads of families living in the open country; for all areas combined, the difference reached approximately 11 percent.

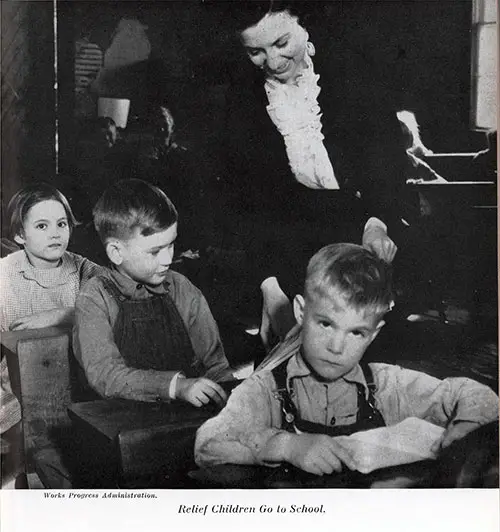

Relief Children Go to School. Photograph by the Works Progress Administration. Rural Families on Relief, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 1530dd3ed9

In the South, Negroes were on a lower educational level than whites. The median school grade completed by heads of white relief families in the Eastern Cotton Area was 5.9 years. In comparison, for heads of Negro relief families, it was only 2.9 years. The median school grade completed for all heads of rural relief families in all areas was 6.4 years.

The contrast between the education of heads and other family members, particularly youth and children, reflects that educational levels have been rising during the past generation. This was most noticeable in areas of low standards where the requirements have been raised rather rapidly and are beginning to approximate the country's standards.

Carle C. Zimmerman and Nathan L. Whetten, Rural Families on Relief: Transmittal Letter and Summary, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Research Monograph XVII, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1938

t

📖 Key Highlights & Findings from the Repor

📌 Four Key Factors That Determined Rural Families’ Need for Relief

According to the WPA study, the main factors that led to widespread economic distress in rural America included:

1️⃣ Employment Levels in the Family – The number of employable adults in a household significantly influenced financial security. Families with few working-age members were more likely to require assistance.

2️⃣ The Business Cycle & Economic Downturn – The drop in commodity prices, factory closures, and economic stagnation forced rural families into poverty.

3️⃣ Weather Disasters & Agricultural Collapse – The Dust Bowl droughts of 1934 and 1936 devastated farms, while floods and crop failures worsened economic conditions.

4️⃣ Long-Term Social & Economic Inequality – Poor education, racial disparities, land depletion, and lack of industrial opportunities kept many rural families trapped in generational poverty.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images

📸 The Faces of Rural Hardship

This monograph includes compelling historical photographs, documenting the human struggle behind the statistics. Some of the most striking images include:

📷 Rural Family on Reli

A haunting depiction of a destitute farm family, captured by the Farm Security Administration (FSA). 🏚️

📷 Farm Owner Family in the Drought Area

A heartbreaking image of a family in the Dust Bowl, standing outside their parched land. 🌾🔥

📷 Tenant Family in the Midwest

A sharecropping family, embodying the harsh reality of landless farmers. 🚜

📷 Lunch Time for Cotton Pickers – A powerful image of migrant laborers barely scraping by in the Western Cotton Region.

📷 Homeless Man & Penniless Widow

Images showing the dire consequences of rural poverty, highlighting those left without any means of survival.

📷 Relief Children Going to School

A hopeful yet sobering reminder that WPA programs provided education opportunities to impoverished youth. 🎒

These photographs bring the statistics to life, providing visual evidence of how families struggled to survive during the Great Depression.

📌 The Different Types of Rural Families on Relief

The report categorizes rural relief families into three major types, revealing the complexity of rural poverty:

🏡 1. Commercial Farmers

🔹 Small-scale entrepreneurs producing cash crops like wheat, corn, and cotton.

🔹 Dependent on commodity prices—when prices fell, their entire income collapsed.

🔹 Highly vulnerable to market shifts and international trade fluctuations.

🌾 2. Non-Commercial & Subsistence Farmers

🔹 Engaged in part-time farming & part-time industrial work (e.g., mining, logging).

🔹 Often self-sufficient, producing food for their own families rather than selling crops.

🔹 Particularly affected by resource depletion (e.g., exhausted coal & timber supplies).

👨🌾 3. Chronically Poverty-Stricken Agricultural Workers

🔹 Tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and farm laborers.

🔹 Dependent on wealthier landowners for wages.

🔹 Often lacked access to relief programs and had no long-term economic mobility.

📜 Regional Analysis: How Relief Needs Varied Across the U.S.

The WPA study divides the country into distinct rural economic regions, highlighting how geography shaped relief needs.

🔹 Cotton Areas (East & West) – Relief depended on landlords; sharecroppers suffered extreme poverty.

🔹 Appalachian-Ozark Region – Self-sufficient farmers survived, but economic mobility was low.

🔹 Corn Belt & Wheat Belt – Highly commercialized agriculture meant fluctuating incomes & farm instability.

🔹 New England & Industrial Regions – Many workers lived in rural villages but relied on urban factory jobs, which disappeared during the Depression.

🔹 Mining & Lumbering Communities – Families in coal towns and timber camps were left stranded when industries shut down.

Each region had unique challenges, but every area suffered from some form of economic devastation.

📚 Relevance for Teachers, Students, Genealogists & Historians

📖 Why This Report Matters for Teachers & Students

✅ Primary Source for Understanding Rural America in the 1930s.

✅ Breaks down how poverty impacted different types of rural communities.

✅ Examines social structures, economic hardships, and government interventions.

✅ Connects the Great Depression to broader themes of economic inequality & resilience.

📜 Why This Report is Essential for Genealogists

✅ Provides specific data on rural employment & relief rolls, helping researchers trace ancestors.

✅ Documents migration patterns, particularly for Depression-era farm families.

✅ Highlights racial & economic disparities, giving context to family histories.

🏛️ Why This Report is a Goldmine for Historians

✅ Explores the intersection of economic policy & social welfare.

✅ Provides rich demographic data on rural families pre-WWII.

✅ Highlights early government attempts at economic reform & social intervention.

⚖️ Discussion of Bias in WPA Research

📌 Potential Biases in the Report

🔹 The study emphasizes economic factors but underplays racial discrimination in relief distribution.

🔹 Southern tenant farmers & Black sharecroppers faced far worse conditions than the report suggests.

🔹 The WPA researchers were government-funded, possibly shaping how they presented relief programs.

📌 Why This Bias Matters

Understanding these biases helps modern researchers interpret historical data more accurately. While the report provides invaluable statistics, it should be read alongside firsthand accounts from rural workers to get the full picture.

🏗️ Final Thoughts: Why This Document Matters

The WPA's Rural Families on Relief study offers one of the most detailed examinations of rural poverty during the Great Depression. By combining economic data, regional analysis, and compelling human stories, this report serves as a powerful resource for anyone seeking to understand how America’s rural communities survived the 1930s.

📌 Ultimately, this document remains an essential historical record that sheds light on the struggles—and resilience—of rural families during one of America's darkest economic periods. 💪🌾