📖 How the WPA Transformed America: Projects, Organization, and Impact (1938)

📌 This WPA report from 1938 details the organization, accomplishments, and economic impact of work relief programs during the Great Depression. A valuable resource for historians, teachers, and genealogists exploring the New Deal’s legacy.

📖 Overview of WPA Projects, Organization, Plans, Operation - 1938

🔨 A Comprehensive Analysis of the WPA’s Impact on Employment, Infrastructure, and Social Welfare

Overview of WPA Projects, Organization, Plans, Operation (1938) provides a detailed assessment of the accomplishments and structure of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), one of the most significant programs of the New Deal. This document, featuring a transmittal letter from Harry L. Hopkins, highlights the evolution of federal relief efforts, the organization of WPA projects, and the tangible improvements made across the country.

For teachers, students, genealogists, and historians, this primary source offers a comprehensive look at how government-funded employment transformed the United States, ensuring economic survival for millions while constructing essential public infrastructure. It also addresses criticisms of work relief and explains the careful balance between public employment and private industry.

Transmittal Letter from Harry L. Hopkins, Administrator of the Works Progress Administration Dated 30 June 1938 for the Book Entitled Inventory: An Appraisal of Results of the Works Progress Administration. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152aa4192b

Transcription of Transmittal Letter

WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION

WALKER-JOHNSON BUILDING

1714 NEW YORK AVENUE NW.

WASHINGTON, D.C.

HARRY L. HOPKINS

Administrator

June 30, 1938

My dear Mr. Président:

For five years, in accordance with Executive orders*, the successive Federal relief agencies under ay direction (FERA, CWA and WPA) have subnitted "periodic and uniform reports" on operations and progress.

These reports have presented in detail the problem of unemployment as we have found it, the manner in which we have met it and the financial considerations Involved. But no attempt has been made, until now, to report in full the actual physical accomplishments of those who have been taken from the relief rolls and put to work at Federal pay.

No such inventory as this has been taken previously because of the transitional nature of the various programs from direct relief to work projects, making the administrative burden of such an undertaking a matter of doubtful justification.

But when the Works Progress Administration had been in operation two full years, under reasonably uniform practices, it provided an entirely justifiable subject far inventory.

This report, therefore, is a detailed examination of the public facilities and services built or performed by WPA workers up to October 1, 1937, obtained by individual inventory of the 150,000 projects that had been operated up to that time. The few selected illustrations of each type of work are for the purpose of giving visual a3 well as narrative evidence of the scope and quality of the works and services. The report also contains, in the form of occasional footnotes or addenda, examples of the relationship between these data and the total accomplishments of all three Federal relief agencies.

Respectfully,

/s/ Harry L. Hopkins

Administrator

*Executive Order No. 7034, dated May 6, 1935.

Executive Order No. 7396, dated June 22, 1936.

Executive Order No, 7649, dated June 29, 1937.

The President

The White House

Spring 1933 Illustration. Inventory: An Appraisal of Results of the Works Progress Administration, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152b074e5a

SPRING...1933

Unemployment is not a new problem in the United States. For 40 years, figures on four major industries indicate that an average of about one out of every ten workers has been out of a job. In 1929, which we now recall as a boom year, estimates indicate that as high as 3,100,000 were unemployed, and an average of 1,800,000 workers were jobless throughout the year.

Throughout this period, the American economic structure grew more complex. Individual craftsmen, who once owned their own tools and were independent business units, were displaced by machines in factories. The men worked at the machines, each performing one small step in the manufacturing process. The economic security of workers came to depend upon holding a job, upon the ability of employers to keep factories operating.

Businesses grew bigger, small ownership decreased, and masses of people in all branches of activity became more dependent upon absentee ownership. Companies operated nationally, ignoring State and local boundaries.

Despite these changes, no tremendous economic jolt came to change our public attitude toward the unemployed. Traditionally, we had assumed that there was something personally wrong with a man who had no job. Welfare agencies studied him and his family life to try to adjust him to society. Similarly, we had assumed that the care of the jobless was entirely a local responsibility. We ignored the fact that business, which provides private employment, was no longer local in character.

The economic jolt came in 1929. Local relief machinery was subsequently swamped by the size of the burden. The States tried to help, but they too were unable to meet the need. Appeals were made to Washington, but Washington was reluctant to break the long chain of precedent.

For more than 2 years, while unemployment mounted steadily, the Federal Government sought recovery by appealing to business for full steam ahead, by urging confidence and neighborliness and generous charity. But such an approach was unrealistic.

At length, in 1932, Congress took the unprecedented step of authorizing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to lend up to $300,000,000 to States and localities for emergency relief. In the spring of 1933, all previous actions had proved inadequate, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was set up, for relief of the needy unemployed.

At the outset, this was a swift, large-scale effort to rush food and clothing and shelter to millions who were in desperate need. For the sake of speed, it was done in the most direct way possible. Federal grants (not loans) were made to the Governors of States, on application, and the Governors made allocations to the official local welfare agencies, which actually administered relief.

Matching of Federal money with State or local funds was urged wherever possible. Nearly all communities carried on work projects at this time, but over half the families were on direct relief.

As the winter of 1933-34 approached, the need for further action became plain. On November 9, the Civil Works Administration (CWA) was created. Its purpose was to provide general buying power and to relieve unemployment by putting 4,000,000 unemployed people to work immediately on public jobs. In essence, about half of them from the relief rolls and half from among the unemployed not receiving relief but registered at the public employment offices.

The CWA largely replaced the early work-relief activities of the FERA on a greatly expanded scale, leaving direct relief to the latter agency.

The CWA went into action with almost incredible speed. It began operations one week after it was created. At the end of another week, 814,511 workers were employed, with a weekly payroll of over $7,000,000. In another week the number was nearly doubled. At its peak, during the week ending January 18, 1934, the CWA employed 4,263,644 workers, and its weekly payroll was more than $64,000,000.

The CWA, unlike the FERA, was Federally operated. All its administrative officers were Federal officials. Moreover, its workers were paid on a straight wage basis. The CWA, designed as only a temporary program, was terminated after four and one-half months. During this time, it operated 180,000 projects and expended more than $934,000,000, of which about $740,000,000 or 79 percent went directly into workers' wages. Also, it bought more than $115,000,000 worth of materials from industry, while equipment rentals and other costs amounted to $79,000,000.

While the CWA built many valuable public improvements, it also provided the Nation's first large-scale experience in public employment of the jobless.

On the knowledge thus gained the FERA, which through the winter (1933-34) had confined itself almost entirely to direct relief, launched a work-relief branch called the Emergency Work Relief Program. This new program took over and finished many incomplete CWA projects. By January 1935, it had reached an employment peak of 2,500,000 persons. At the same time, a somewhat higher number were receiving aid through FERA direct-relief activities. But these were heads of families. When their dependents are included, more than 20,000,000 people were receiving assistance.

Works Progress Administration: Organization-Plans-Operation Illustration. Inventory: An Appraisal of Results of the Works Progress Administration, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152b48ee4a

WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION: ORGANIZATION-PLANS-OPERATION

The valuable experience gained through the CWA and the FERA had taught Federal relief officials several things.

They had realized early that direct relief tends to destroy both self-respect and skill, while useful public work tends to preserve them.

They had learned that while work projects cost more than direct relief, the expenditure results in useful public improvements, which constitute national wealth.

They knew that the cost of these programs, while significant, was trivial when compared to the economic loss as the result of unemployment. The national income produced in 1929 was more than 80 billion dollars. In 1932 it was less than 40 billion. In any single depression year, the loss in national income was many times greater than relief expenditures.

Back when almost one out of every three American workers had been jobless, the public had readjusted its attitude toward the unemployed. When only a few people had no work, it was assumed that something was wrong with these people. But when one-third of the Nation's workers had no jobs, it became plain that all these people could not possibly be maladjusted—that it was the system which was out of gear. All that ailed most of the unemployed was the lack of work.

One of the objects of the jobs created to meet this need was to keep the workers fit for an ultimate return to private occupations. And every succeeding day of work-relief strengthened the conviction that the way to do this most successfully was to diversify the program so widely that the workers could be given the kind of work at which they had the most talent or experience. Experimentation in this direction had been begun under the CWA. It carried on extensively under the FERA, which instituted special programs for impoverished farmers, transients, college students, and "white collar" workers. By mid-1935, the lessons of the previous 2 years had evolved into a definite pattern of policy. Briefly, it was this:

The physically unfit, the aged, and all other unemployable persons were to be the responsibility of the States and local communities. Still, supplemental Federal aid was provided through the Social Security Act for a large portion of this group if the States agreed to cooperate.

The needy, able-bodied unemployed, who are the victims of Nationwide rather than local conditions, were to be the responsibility of the Federal Government.

This was the basis for the Works Progress Administration, which replaced the FERA in the latter part of 1935, and which concerned itself exclusively with the providing of useful jobs for the needy, able-bodied unemployed. The WPA's big drive to provide jobs was supplemented by the expanded activity of about 40 other Federal agencies from emergency funds.

The WPA program is primarily Federal in character, yet it leaves to local determination several basic steps. For example, all non-Federal WPA projects (and 98 percent are non-Federal) are originated, planned, and sponsored by local or State governmental bodies.

The WPA then reviews them for engineering soundness, availability of labor, legality, financing, and numerous other definite points of eligibility. The WPA also controls the timing of operations. Thus the local communities determine the nature of their own improvements or services. The Federal Government enforces general aspects of law and adapts activities to fit budgets and other operating requirements.

A similar division of authority was arranged concerning the selection of workers. Local welfare agencies determine the need of applicants for jobs and certify them to the WPA for work. The WPA then employs them as operations permit.

Mostly, this revised model of a work program, taking advantage of all previous experience, has been operating with few fundamental changes throughout the entire life of WPA.

Minor changes have been in progress almost always. Added safeguards have been formulated to prevent the use of WPA projects for regular operations of local governmental units. Stress is placed upon work, which is non-competitive with private industry. The average of sponsors' contributions has risen steadily from 12 to 20 percent of all project costs.

The maximum proportion of non-relief workers permitted on projects in any State has been reduced from 10 percent to 5 percent of the Federal payrolls. On a Nationwide basis, less than 3 percent are non-relief workers.

Rapid and flexible methods have been worked out by which large numbers of WPA workers can be shifted quickly from their project work to private jobs when temporary labor needs are acute, or to relief and rescue work at the scenes of disasters.

Example: In December 1937, Louisiana sugarcane growers faced a severe emergency. A $6,000,000 cane crop was frost-bitten in the fields and had to be cut at once lest it thaws and ferments. State WPA officials met with the Governor, labor leaders, and railroad representatives. Wages and working conditions were agreed upon, transportation provided, and many hundreds of WPA workers moved out quickly from New Orleans and Baton Rouge, saving the bumper crop.

A close relationship is maintained with the United States Employment Service to bring WPA workers into contact with those jobs that are available.

Thus the Nation is learning to use to advantage the country's emergency labor surplus. During periods when industry cannot use these workers, WPA jobs permit them to sustain their families while "keeping their hands in" at the kind of work for which they are best qualified.

On the question of involuntary unemployment, U. S. Surgeon General Thomas Parran said in March 1937:

"I speak not as an economist but as a doctor when I urge that useful employment be provided for all who are willing and able to work. Whatever the cost, I would urge that from the standpoint of public health in its larger concept—of mental health—economic factors are subordinate to the vital necessity of providing for our destitute citizens an opportunity of a livelihood earned by individual effort."

WPA Projects: Federal and Local Participation. Major Types of Occupations on WPA Projects -- Each Figure Represents 5 Percent. Inventory: An Appraisal of Results of the Works Progress Administration, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152b4b253b

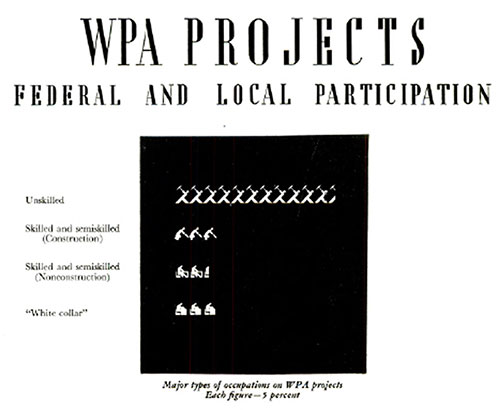

WPA PROJECTS FEDERAL AND LOCAL PARTICIPATION

- Unskilled

- Skilled and semiskilled (Construction)

- Skilled and semiskilled (Non-Construction)

- "White-collar"

Significant types of occupations on WPA projects. Each figure=5 percent

The WPA has twin objectives: First, to give public work to people in need of jobs, and second, with those people to build useful public improvements or perform useful public services.

Improvements or services requested from the WPA by officials of any community must (1) provide the kind of work which people on the local WPA rolls can perform, and (2) be publicly useful work, on which local funds make up most of the non-labor costs involved.

The WPA's initial concern is with people in need of work. For example, 2,000 people in Jones County . . . not just any 2,000 people, but 2,000 specific individuals whose names and addresses and work-experience have been listed by the Jones County welfare authorities.

Traditionally, public work is a way of creating a school or a road or providing a service for public use. Building the school is the primary idea. That it gives work is only incidental.

With the WPA, however, public work is a way of using or salvaging labor that otherwise would waste in idleness. The WPA begins with the people who need jobs. They are employed so that they can earn a living, and useful work is selected, from among the community's needs, which they can do well.

In trying to find jobs for the unemployed, the WPA sets up varied checks and balances.

To achieve the most relief with Federal funds, it requires that the bulk of the Federal money must go directly to the workers in wages.

The Federal government requires that most of them (98 percent, in practice) be originated, planned, and requested by local officials to ensure WPA projects are locally desirable and useful.

To make sure that projects are really needed, it requires that each community supplement the Federal money with local funds, which are used principally for the purchase of materials and other non-labor costs. On average, local communities are spending $1 to every $4 spent by the WPA. The WPA declines to go far beyond the payment of the workers' wages.

Incidentally, while this policy has conserved Federal funds, it has not prevented large purchases of materials from industry for use on WPA projects. Through October 31, 1937, these material and equipment purchases totaled $520,824,208.

Cement, crushed stone, sand and gravel, brick and tile, and other stone, clay, and glass products made up one-third of this amount or $175,124,046. At the same time, roughly one-fifth went for iron and steel products exclusive of machinery, or $97,064,629.

Other selected items: Machinery and equipment, $21,930,373; lumber and its products, $56,721,557; textiles, $40,502,566; bituminous paving materials, $45,613,455; plumbing equipment, $6,056,929; paints and varnishes, $9,212,212; and other miscellaneous materials, $68,598,441.

The Federal government requires that WPA work must be added to that planned or normally included in local budgets to protect the workers on local government payrolls. In other words, if WPA workers were to displace regular clerks in a city hall, there would be no employment gain.

For the workers themselves, the WPA requires that projects be provided in each community that is adapted to the training, ability, and experience of the persons in that community who need work. For, since the purpose of the program is to keep or make unemployed workers fit for a return to private jobs, they should be given work at their best aptitudes wherever possible. As an extreme example, a professional violinist's hands might be ruined by a year's work with pick and shovel.

To better understand the operation, let us take a hypothetical community with 100 needy employable persons and a total of $100,000 in federal and local funds available to keep them at work for a year.

First, here are the occupational characteristics of the 100 people: 4 carpenters, 2 bricklayers, 2 painters, 1 electrician, 2 plasterers, 4 truck drivers, 18 mill operatives (male), 8 mill operatives (female), 22 unskilled laborers, 3 bookkeepers, 1 barber, 4 stenographers, 2 automobile mechanics, 1 radio operator, 3 real estate agents, 2 boilermakers, 1 locomotive engineer, 1 music teacher, 1 millwright, 1 baker, 2 welders, 1 detective, 4 janitors, 2 elevator operators, 1 shirt maker, 2 woodchoppers, 3 cigar makers, 2 teachers.

The Mayor asks the local WPA representative to meet with the City Engineer and council. The Mayor already has a list of projects the city has needed for a long time. Outstanding is the need for a new junior high school.

The four-room building which has been planned is not large enough to warrant status as a Public Works Administration project. It is decided that the 4 carpenters, the 2 bricklayers, the 2 painters, the 2 plasterers, the electrician, 2 of the truck drivers, and 8 of the unskilled laborers can be used to build the school as a WPA project.

The amount of $20,000 to cover this work is agreed upon, the city contributing $6,000 for the hire of 1 supervisor, 1 foreman, and 1 steamfitter, not on relief, and for purchase of necessary material.

The next project decided upon might be the paving of 12 blocks on Main Street. This project would take 10 of the 18 male mill operatives, 10 of the unskilled laborers, 1 of the bookkeepers, the 2 remaining truck drivers, 2 of the janitors, and both of the woodchoppers. It might be approved in the amount of $27,000, with the city contributing $5,000 for materials.

The third project might be a sewing room designed to give employment to the 8 female mill operatives, 1 of the stenographers, and the 3 cigar makers. This project would be approved for $12,000, with the city contributing $2,000 in the form of material. The products of the sewing room would, of course, be given to local welfare agencies for distribution to needy unemployable people.

And so the conferees would go down the list, selecting projects of various kinds, until some sort of work was provided for the 100 destitute unemployed. A reservoir of other projects was made available for future needs and for changes in the numbers or aptitudes of the unemployed. Something like this has occurred in nearly every community in America.

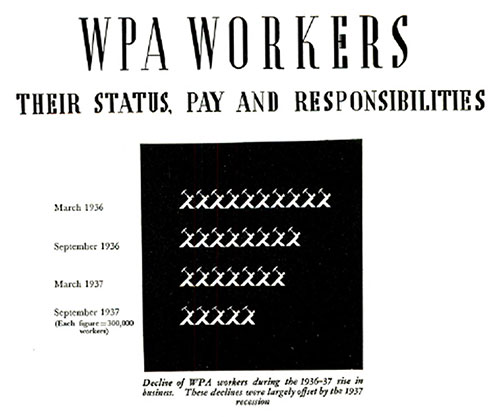

WPA Workers: Their Status, Pay, and Responsibilities. Decline of WPA Workers During the 1936-37 Rise in Business. These Declines were Largely Offset by the 1937 Recession. Inventory: An Appraisal of Results of the Works Progress Administration, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152b9bf4e0

WPA WORKERS THEIR STATUS, PAY AND RESPONSIBILITIES

March 1936 September 1936 March 1937 September 1937 (Each figure = 300,000 workers) Decline of WPA workers during the 1936-37 rise in business. These declines were primarily offset by the 1937 recession.

Every man or woman who draws a wage check from the WPA does so for work he has performed. The WPA pays no "direct relief." Its purpose is to provide jobs for able-bodied unemployed persons from relief rolls who are in need, leaving "unemployable"—those who are unfit for work because of age or illness or physical handicaps—to the care of States and local communities.

The eligibility of workers for WPA jobs is determined by the local welfare agencies, who "certify" them by name to the local WPA officials as being in need and capable of work.

Only one member of any relief family unit is permitted on the WPA rolls. However, a younger member may be enrolled in a CCG camp or on an NYA project.

The average monthly earnings of a WPA worker are about $52. Individual earnings vary downward in rural areas where living costs are low and upward in large cities where they are high. The wage scale is higher for skilled and semiskilled workers than for unskilled.

WPA workers are paid the prevailing hourly rate for any given class of work. Still, the number of hours they work each month is determined by the established schedule of their monthly security earnings.

Masses of data on file in the WPA's Washington office attest specific facts about WPA workers which are not generally understood:

- They are not a fixed group of economic outcasts but continuously move in and out of private industry in impressive numbers. Moreover, they represent a cross-section of the working population.

- The vast majority of them do not want charity, but merely a chance to work.

- The majority of those with previous experience in industry have good work-records in private employment. Their average length of employment with a single firm is 5 years.

- They do not refuse private jobs at reasonable working conditions and pay.

- The most challenging group, from the standpoint of readjustment into private jobs, is composed of young people in their early twenties, with neither business experience nor the opportunity to acquire it. A lesser, but also important group, embraces workers over 40 or 45 who have passed their peak and are not wanted by private employers when experienced younger workers are available.

The fact that the WPA rolls are highly sensitive to the private-job situation is illustrated by the drop from over 3,000,000 WPA workers in March 1936 to 1,448,000 in October 1937— a decrease of more than 50 percent. Of a total of about 5,000,000 persons who had worked on the WPA program through November 1937, less than one-sixth (760,646) were employed continuously throughout this period.

The overwhelming desire of these needy people to work for what they get, rather than receive charity, is reflected in the letters they write to the WPA. Two out of three of the letters from unemployed workers are simple requests for a chance to work.

Heeding the often-heard charge that WPA workers refuse to leave the rolls to take private jobs, the WPA has investigated every specific allegation of this type that has come to its attention during the past 2 years. Of the thousands of people involved in investigations, the number actually found to have refused private jobs unjustifiably is so small as to be insignificant. In such cases, the guilty workers were promptly severed from the WPA.

These investigations revealed an active desire on the part of local WPA officials to meet private labor demands. During harvest seasons, projects have been curtailed or suspended in many localities to provide field workers. The officials have refused, however, to force WPA workers into private jobs at substandard pay, or under obviously unfair working conditions.

Some typical cases:

A Philadelphia produce firm charged that there was an acute shortage of cannery and field workers in Delaware and Maryland because of the refusal of relief workers to take private jobs. An investigator visited 21 canneries listed by this firm and 8 others. Thirteen of the 29 plants were not operating, 15 needed no labor.

A letter to Washington said farmers in western Kentucky couldn't get farm hands because of the WPA. The author of the letter, when interviewed, said he needed no help and knew of no other farmers who needed help. He admitted he wrote the letter in anticipation of a possible shortage during the fall harvest.

A council of contractors charged that the WPA was responsible for lack of electricians, and offered to hire all those released by the WPA. The records showed that there were 142 electricians on WPA projects in the State, but there were also 224 others registered as seeking jobs who had no work at all. The council apologized but hired no men.

While the WPA rolls include a somewhat abnormal proportion of the workers over 40 or 45 whom industry is reluctant to employ, they also contain hundreds of thousands of young men and women in their early twenties whom the CCC and NYA programs have been unable to absorb.

The older workers on WPA rolls are there, not only because industry views them askance, but also because of the tendency on the part of local welfare authorities, in certifying relief recipients for jobs, to give preference to the heads of large families.

On the other hand, the vast number of inexperienced young people entering the labor market is the most severe problem of all. The youngster who is a breadwinner is eligible for a WPA job. But backed up in the homes of relief families, from coast to coast, are an army of older sons and daughters.

They cannot get private jobs, cannot get placed with the CCC or NYA, and are ineligible for the WPA because one of their parents already has a single WPA job, which is permitted per family.

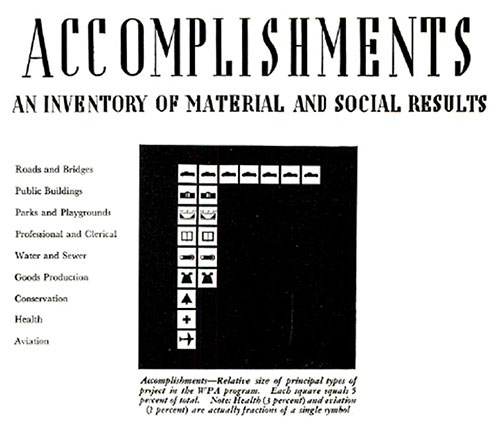

Accomplishments: An Inventory of Material and Social Results. Accomplishments--Relative Size of Principal Types of Projects in the WPA Program. Each Square Equals 5 Percent of Total. NOTE: Health (3 percent) and Aviation (2 percent) are Actually Fractions of a Single Symbol. Inventory: An Appraisal of Results of the Works Progress Administration, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938. | GGA Image ID # 152c1bfc00

ACCOMPLISHMENT!! AN INVENTORY OF MATERIAL AND SOCIAL RESULTS

Roads and Bridges Public Buildings Parks and Playgrounds Professional and Clerical Water and Sewer Goods Production Conservation Health Aviation Accomplishments—Relative size of principal types of projects in the WPA program. Each square equals 5 percent of the total. Note: Health (3 percent) and aviation (2 percent) are actually fractions of a single symbol

The public improvements which WPA workers have built or the public services they have rendered are national assets and, in the opinion of many economists, adequately deductible from the cost of work relief when it is compared with any other method of aiding the unemployed.

In this report, however, no such deduction is attempted. The actual accomplishments of the WPA are merely stated in detail so that any interested citizen may draw his own conclusions.

First, it should be realized that nearly 80 percent of all WPA funds are spent on construction work because most of those eligible for WPA jobs are best fitted for this type of work.

Breaking this down into types, well over one-third of the Federal funds spent on the WPA program goes for highways, roads, and streets; 10 percent for water facilities, sanitation, and other utilities; about 11 percent for public buildings; another 11 percent for parks and playgrounds and other recreational facilities; nearly 5 percent for conservation work; and about 2 percent for aviation facilities.

About one-fifth of the WPA program is devoted to non-construction projects of all types. Sewing projects are the most significant type in this group, aggregating more than 7 percent of the total WPA activity. In contrast, professional and clerical projects make up almost as massive a total. The emergency education program represents slightly more than 2 percent, the recreation program somewhat less than 2 percent.

This proportionate distribution of WPA expenditures—$4 for construction projects to every $1 for non-construction—is stressed because, in the succeeding sections of this report, space is not given according to the relative size of each activity in the WPA program.

The highway, road, and street program, for example, involving more than one-third of both the funds and the workers, is detailed in a single section. Reason: Construction of roads, streets, bridges, and culverts is well understood.

The four Federal arts projects (music, art, theatre, and writers), on the other hand, are given four complete sections. However, they involve an aggregate of about two and one-half percent of the WPA program. Reason: The purposes behind public employment of jobless professional and technical workers at work they are best suited for are not well understood, nor are the accomplishments of these workers.

How are the data gathered for this report?

To each of the 158,000 WPA projects which had been operated throughout the United States was sent a detailed inventory form, with space upon it for the most important types of physical accomplishments related to that type of project. In this form, the completed work was listed in detail, checked by statistical field offices, and returned to Washington. Here the accomplishments were tabulated by States and on a national basis.

The figures on succeeding pages of this report represent only work which was completed on October 1, 1937, the date on which the inventory was taken. A vast amount of additional work, in progress at that time but incomplete, was not included.

Many previous reports have been made on the progress of the Works Program, giving special attention to the distribution of projects and funds, data on unemployment, workers, wages and hours, and general operating practices.

This, however, is the first detailed report which has concerned itself solely with the physical accomplishments of the Works Progress Administration, together with a scattering of authoritative comments on the quality of those accomplishments.

In the opinion of thousands of city, county, and State officials who participated in a recent national survey, few of the improvements and services listed on the following pages of this report could have been accomplished without the aid of the Federal Government and the unemployed.

"Overview," in Inventory: An Appraisal of Results of the Works Progress Administration, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938, (Transmittal Letter), pp. 3-12.

Why This Document is Important

📜 Relevance for Different Audiences

✔ For Historians & Researchers

🔹 Provides official WPA data and statistics, offering valuable primary source material.

🔹 Explains the federal relief strategy, highlighting shifts from direct relief to work relief.

🔹 Clarifies the relationship between federal and local governments in public works projects.

✔ For Genealogists & Family Historians

🔹 Useful for tracing ancestors who worked on WPA projects or were affected by federal relief.

🔹 Explains employment classifications, wages, and working conditions of WPA workers.

🔹 Identifies key industries and occupations tied to government relief programs.

✔ For Teachers & Students

🔹 Supports lessons on the Great Depression, the New Deal, and government intervention in the economy.

🔹 Breaks down how relief efforts were structured and implemented at national and local levels.

🔹 Presents statistical data that can be used for historical analysis.

📌 This document is a goldmine of historical information, providing a structured view of the WPA's accomplishments and its long-lasting impact on American society.

::::: Most Engaging & Insightful Content :::::

📜 The Transition from Direct Relief to Work Relief

✔ Why This is Fascinating:

🔹 The early 1930s relief efforts focused on direct cash assistance, which eroded self-respect and did not contribute to economic recovery.

🔹 The WPA’s shift to work relief created jobs while building essential public infrastructure, a model that remains influential today.

✔ Key Takeaway:

🔹 The federal government learned that work-based relief was far more effective than direct handouts.

🔹 Public works projects not only provided jobs but also created lasting improvements in infrastructure, education, and social services.

🛠️ How the WPA Operated: A Well-Organized Workforce

✔ Why This is Fascinating:

🔹 The WPA did not just hire workers randomly; it carefully matched local unemployed people to relevant jobs.

🔹 Projects were initiated by state and local governments, but federal oversight ensured efficiency and prevention of corruption.

✔ Key Takeaway:

🔹 The WPA’s strategic organization ensured that workers contributed meaningfully to their communities.

🔹 A strict hiring process and project review system prevented abuse of federal funds.

📌 This section highlights how the WPA balanced federal control with local decision-making, ensuring that projects addressed real community needs.

📊 The Economic and Social Justification for WPA Spending

✔ Why This is Fascinating:

🔹 Critics of government spending argued that WPA programs were costly, but this report proves otherwise.

🔹 Comparison of national income loss during the Great Depression vs. WPA expenditures shows that the cost of inaction was far greater.

✔ Key Takeaway:

🔹 Government spending on employment programs prevented economic collapse.

🔹 The WPA built valuable infrastructure that benefited the nation for decades.

📌 This section effectively challenges the misconception that work relief was wasteful, proving that WPA projects were strategic investments in America’s future.

🖼 Noteworthy Images & Their Significance

🖼 📜 Transmittal Letter from Harry L. Hopkins – Official endorsement of the WPA’s accomplishments, reinforcing its legitimacy as a federal program.

🖼 🌍 Spring 1933 Illustration – Visual representation of the economic crisis before WPA intervention.

🖼 🏗️ WPA Organization-Plans-Operation Diagram – Breakdown of how federal and local governments coordinated WPA projects.

🖼 📈 WPA Employment & Recession Graphs – Data showing how WPA employment rose and fell with private industry trends, proving it was a safety net rather than a permanent workforce.

🖼 🌉 WPA Accomplishments Chart – Visual representation of completed infrastructure projects, emphasizing the scale of WPA’s impact.

📌 These images reinforce the data-driven success of the WPA, making the report both informative and visually compelling.

Bias & Perspective Considerations

✔ Pro-WPA Tone:

🔹 The report is strongly supportive of the WPA, highlighting successes while downplaying inefficiencies.

🔹 Statistics and data focus on the positive impact of WPA projects, rather than potential shortcomings.

✔ Underrepresentation of Criticism:

🔹 The document does not address criticisms of WPA bureaucracy, inefficiencies, or potential political motivations behind project selections.

🔹 Private industry concerns about government job competition are briefly mentioned but dismissed.

✔ Selective Data Representation:

🔹 The economic impact of WPA spending is framed as entirely positive, but alternative economic theories about recovery strategies are not explored.

📌 While the report is a fantastic primary source, researchers should supplement it with additional perspectives to get a full picture of WPA successes and challenges.

Final Thoughts: Why This Report Matters

"Overview of WPA Projects, Organization, Plans, Operation (1938)" is an indispensable document for understanding how the United States government tackled mass unemployment during the Great Depression.

It provides:

✔ A structured look at federal relief efforts and their evolution.

✔ A compelling defense of work relief programs, backed by economic justifications and statistical data.

✔ A blueprint for modern public works programs, offering lessons for contemporary policy-making.

For teachers, students, genealogists, and historians, this report is a treasure trove of primary source material, illuminating one of the most ambitious government employment programs in U.S. history. Whether analyzing economic policies, social welfare, or public infrastructure development, this document is a must-read for anyone exploring the impact of the New Deal.

WPA projects shaped the modern American landscape, and this report proves why their legacy endures. 🏗️📚📊