The Telephone Girls of St. Mihiel - 1921

On 19 March 1918, the Services of Supply (S. O. S.) was formed, with headquarters at Tours, superseding the Lines of Communication. A week later, the first unit of women telephone operators arrives and introduces a new efficiency element into A. E. P. telephone operation.

A Busy Hour at Tours Central Office. Chief Operator Marion Swan Is Watching the Work of Her Operating Force. Circuits of Victory, 1921. GGA Image ID # 19a1773738

However, relates one of the girls, "When it was rumoured that there was a possibility of our having to leave, there was hearty protestation. The telephone business, we felt, had become well-nigh unmanageable on account of the drive going on, and it seemed to us that to put inexperienced boys in our places might prove disastrous."

Headquarters gave them one day more. That, they were told, would be the limit.

In that one day, the tide had turned. The girls never left their switchboards.

On Duty at St. Mihiel. American Telephone Operators on Duty at First Army Headquarters Equipped with Gas Masks and Helmets Ready for Use on a Moment's Notice.

The New England Bell Telegraph Battalion, too, took part in the St. Mihiel action.

"Of the Four Hundred and First Telegraph Battalion," reports the Chief Signal Officer, "one company concerned itself chiefly with the Army Signal Eepair Shop, while the remainder of the battalion engaged in the construction of fundamental circuits."

Not the least part of the credit for the brilliant finesse with which the St. Mihiel salient was pinched out in the brief course of 48 hours is due to the remarkable ease and facility with which the operators handled the telephone communication at Army Headquarters. This glorious bit of American history was written by six plucky girls who eagerly jumped at the chance of doing their bit in the fighting area in and about St. Mihiel.

It was the work of these girls that moved Don Martin, veteran war correspondent of the New York Herald, who lost his life in France, to observe that the efficiency of the American Army switchboard was "as complete as that of a financial institution in Wall Street. There is no delay.

In dozens of instances, officers called up headquarters miles away during the severest fighting; they got a reply instantly—never a delay. The efficiency of American business methods, which it was hoped would be gradually developed in the war machine, even during such excitement, has been realized, and that is one of the reasons why the operations went through so quickly and cleanly."

The moving spirit originating from the demand for women operators was Colonel Parker Hitt, Chief Signal Officer, First Army. Hitt was from the very start an ardent advocate of the use of women operators in France.

On 18 August 1918, two days before the preparations had begun for reducing the St. Mihiel salient, Hitt wrote to the Chief Signal Officer: "In order to obtain maximum efficiency of the telephone central at advance army P. C, I desire to use women operators, to be taken from those especially qualified by their familiarity with frontline work and code station work. I will have the facilities for a small number of these operators at the proposed P. C, and no difficulties need be anticipated along this line."

At once, the call went out among the 225 women operators in France for a unit of six operators to serve at the front, and at once, every girl of the 225 responded that she wanted to go.

"We were all just dying for a chance to go up forward," writes one of the disappointed ones, "and the mean things would let only six of us go."

It was not an easy thing to make so important a selection.

"In view of the fact," says the Report of the Chief Signal Officer, "that the Army had to handle an immense amount of telephone communication with the French armies on its right and left, with French corps in the Army, with the French group of armies, and finally with General Headquarters, it was obvious that a most important requirement for these Army operators was the ability to speak French as well as they spoke English.

At the same time it was necessary that they be excellent operators and in good physical condition so as to stand the strain of their work and the possible hardships of living in the Army area."

The commanders finally made the selection. "Miss Julia Kussel, of the YWCA, who had charge of the operators' hostess house at Chaumont, made the necessary arrangements for billets and a mess for six operators and herself in Ligny.

When those arrangements were complete on 25 August, the Chief Signal Officer, American Expeditionary Forces, was notified, Chief Operator Grace D. Banker, and Operators Ester V. Fresnel and Suzanne Prevot were sent by automobile from Chaumont to Neufchateau. They were there joined by Operators Helen E. Hill, Bertha M, Hunt, and Marie Lange, and the six proceeded to Ligny by automobile."

The story of what these girls did during that exciting period when the enemy was being squeezed out of the St. Mihiel salient by the mighty pincers of the First American Army —a period during which the girls stuck to their tasks day and night in broken shifts, handling an average of 40,000 words a day over the eight lines leading out of the Ligny (Note 1) board,—is a story best told by the girls themselves.

Writes Ester Fresnel, in a letter to her parents:

France, Near the Front,

Sunday Night, 15 September 1918.

My Dearests:

There is so much to tell you that I simply don't know where to start. But I must raconteur all about this last wonderful victory of ours, or I'll choke.

I suppose by the time you get this letter you will have heard all about it through the papers, but "neanmoins" I want to let you know the part we imagine we played in it.

In the first place, before and while this "stunt" of ours was pulled off, we were rushed to death; we worked day and night, six hours at a stretch, and then ran home to snatch a few hours' sleep then go back to work.

The strain was pretty bad; officers were all on edge, and it was rather hard to keep our tempers at times because everything came at once, and dès fais the lines would go out of order, bombs or thunderstorms up away.

Still, the communications had to go through; men would ask for places we had never heard of and wanted them immediately.

Sometimes it would take us over an hour to complete a call.

Altogether we were all very excited and just strained to the utmost.

Then all at once, something seemed to come over everybody.

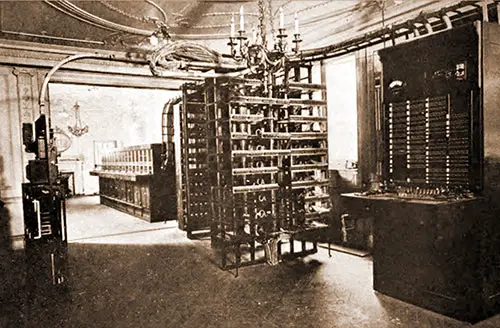

Art and Science. Terminal and Operating Room, Elysee Palace Hotel, Paris, France, 6 May 1918. the U. S. Signal Corps' Telephone Installation Men Were Cautioned to "do the Job Artistically." Official Us Army Photograph. Circuits of Victory, 1921. GGA Image ID # 19a18ffa93

Their voices were not so harsh —they almost said funny things to us over the lines. "We would call for places in the most dulcet of tones, even though we were dead tired, and we knew even before we were told that the whole thing had been successful.

"And," adds the brave little lady, "last night we went to bed instead of working, the first time in 72 hours."

Mrs. B. M. Hunt, of Berkeley, California, writes to her "old boss," Mr. Prescott, of the Traffic Department, Pacific Bell Telephone and Telegraph Company:

My! How we did long for that drive to begin; we were weeks waiting for it, watching the troops pass, the artillery rumble by, the trucks constantly going day and night—supplies and men passed continuously until we thought all America had been sent over.

Special lines, called "operation lines," were put on our switchboard and were only to be used in connection with the drive. It was most thrilling to sit at that board and feel the importance of it—at first, it gave me a sort of "gone" feeling for fear the connection would not be made in time and a few seconds would be lost, but soon the responsibility of it sort of calmed me and, as in all things that occur many times in our lives, became ordinary and lost its thrill.

The night the drive began we were called to the office—before that, men operated between 10 P. M. and 7:30 A. M.—and for the three days during the attack, we were on four hours and off four hours.

And Helen E. Hill, a New England miss, gives her account of the engagement:

We have been playing our little part in this last big salient.

One morning we were called at 2:30 o'clock to go on duty, and for the next 48 hours, I, for one, had only four hours' sleep. We worked 12 hours in broken shifts, the "broken" part being the hard part, since it was very difficult to come home, eat, and get to sleep for only a short while.

At the office, which used to be a French dining room, there is a fireplace which the boys would fill with wood for a nice warm fire, and we found it quite entertaining to sit through the night until dawn. There was always a Wire Chief and soldier-operator on duty in case we needed help.

I amused myself, also, by swapping stories over the wire with different soldier operators when they would call in to test the lines. We had to test frequently to see that everything was in readiness in case of emergency. One said his office was underground 40 feet and was very cold and clammy.

You can imagine that there was much excitement among the members of the First Army. The officers were getting no sleep and were sometimes impatient to us, but we kept our tempers fairly well and gave every ounce of endeavor that was in us.

Nor did it have a marked effect on any of the girls. One could see the dark hollows under their eyes, but not a change in their usual happy voices.

Now, of course, it is over, for a while at least, and we are all getting our hearty sleep and none the worse for wear. On the contrary, I have gained a whole lot of self-control and patience and am awfully proud of having had such a real part to play in this great salient of St. Mihiel.

Brilliant and vital as was the part played by these plucky women operators right in the advance zone of combat, we must not forget the part that was played during this and the succeeding major engagements by the male telephone operators in the muddy dugouts down in the bowels of the earth.

Some of these operators, indeed, were so far down as to be scarcely aware, so far as noise was concerned, of the terrific duel going on over their heads. But so far as traffic was concerned, they knew only too well the mighty activity going on about them. Indeed, it moved through them in a surge of incessant and breathless messages, and they worked until they dropped from sheer exhaustion.

Operating Room at Toul, France. Telephone Girls Are Operating the Exchange at Second Army Headquarters, Toul, France. Note the Portable Army Switchboard, Resembling an Army Locker, in the Background. Official US Army Photograph. Circuits of Victory, 1921. GGA Image ID # 19a2106d69

Other dugouts were not so far removed from the surface, and the tremendous impact of the guns overhead, adding to an intense, overpowering thud, was doubly deafening.

Nor must we forget the work of the subterranean telegraph operators, clicking away at their instruments in the midst of all this inferno, with no sound of a human voice to relieve the strain.

A picture of what these telegraph operators had to contend with is furnished by F. M. Henson, of the Engineering Department of the Michigan State Telephone Company:

We arrived at St. Mahiel shortly after dark, and at once, the entire detachment prepared to get into the fight. As upon all other occasions, our friend and enemy, the M. P.'s, escorted the telegraph operators to telegraph offices nine to twelve feet underground and hear the sound of the howling.

The bursting shell was almost as loud as on top of the ground. If the doughboys up in the first line trenches were getting it worse than we were, and they sure were, I felt sorry for them, for the shells were coming down as thick and fast as hail; not hell, but hail, and I mean it. I could hardly hear my telegraph set above the noise.

The ground shook, and mud fell from the sides and roof of the "telegraph office," but we kept the wire working as fast as it could be worked.

For three days and nights, I was on duty, and it seemed as if it were that many months, but finally, it grew less violent, and as soon as advisable, I was relieved and told to report back to Issurtille, and I did, and long after those three terrible days and nights at St. Mihiel I found I was so nervous, that every sudden sound or falling of something, or slamming of a door, would cause me to jump as if I had sat on a tack.

And finally, while we are on the subject of telephone operators at St. Mihiel, we must not fail to give passing notice to the splendid and all-important work done by the telephone operators attached to the artillery units, of whose work Major Nels Anderson, Wire Chief of Chanute, Kansas, for the Southwestern Bell Telephone System, has this to say :

The best dugouts obtainable were used for the telephone switchboards, and they were gas-proofed as much as possible; but even at that, it was necessary at times for the operators to use gas masks.

God knows it was hard enough to operate a switchboard without the gas mask, but when it was necessary to use them and maintain communication, life became nearly unbearable.

It was particularly bad during the St. Mihiel party, where we were unable to get undercover with our switchboards. They were set up in the open, and as we were getting lots of gas, the masks had to be worn almost continually.

I would like to put a gas mask on you sometime, and then have you try to talk over a telephone, then make a dash across country for a mile or so with somebody throwing brickbats at you at every jump, and then try to splice a wire.

Operating Room at General Headquarters, Chaumont, France. The Paris Headquarters of the A. E. F. Had Instructions to Prepare for Removal at a Moment's Notice. The Signal Corps "Hello" Girls Were Warned to Have Their Bags Packed and to Be within Calling Distance at All Times. Several Army Trucks Were Kept in Readiness in the Garage Adjoining, Prepared to Whisk These Girls Away on a Moment's Notice. Circuits of Victory, 1921. GGA Image ID # 19a1d5d596

This would give you some idea of the ordinary work which we had to go through with. There are lots of unhonoured heroes among these telephone men who deliberately took a dose of gas, which many times resulted fatally, by taking off their masks in order to get some communication through satisfactorily.

It was all, in fact, a splendid example of Signal Corps co-operation throughout the entire A. E. F. Not much, indeed, was left undone that might have been anticipated.

Not many have stopped to consider how General Russel managed to secure such splendid facilities on such short notices for the extended requirements of the First Army at St. Mihiel, and this is a matter which involves a certain amount of dramatic irony.

A large part of the signal equipment which aided in the destruction of the enemy salient was originally designed for use several months back when fear of destruction by the enemy was the order of the day.

It will be recalled that at the time the German advance threatened Paris, a complete duplicate of the American wire communication system in Paris—a knockdown system—was awaiting emergency use at the great supply center in Gievres, ready to be replied to Paris on a few hours notice in case the Paris system of wire communication should be destroyed by a bomb or long-distance gun.

When the First Army came into existence, the first tentative plan was to establish the army field headquarters in the retaken Mame salient. The establishment of an army headquarters involves the construction of a very considerable telephone exchange and telegraph office.

Realizing that, with the check which had been administered to the Germans at the Marne, the whole course of events had changed for the Allies, the Signal Corps took a chance and ordered the duplicate Paris installation held at Gievres to be partially shipped to La Ferte for emergency use by the First Army.

Instructions covering this shipment were given by telegraph to Gievres, and this shipment, which consisted of approximately ten carloads, was loaded and was moving toward the front within less than three hours.

And thus was the Signal Corps enabled to furnish a wealth of telephone facility for the St. Mihiel effort, which proved to be the heart and soul of the marvelous teamwork displayed in that historic engagement.

Note 1: It was here that the Advance of Echelon of the First Army had established the Post of Command.

A. Lincoln Lavine, "Chapter XLII: St. Mihiel," in Circuits of Victory, New York: Country Life Press/Doubleday, Page & Company, 1921, pp. 490-497+.