Switchboard Soldiers of the Great War

Signal Corps Telephone Exchange Switchboard at Bordeaux, Gironde, France. At Switchboard, Left to Right: Miss Laborde; Miss Fairbrother; Miss Dickerson; Miss Blanc; Miss Knall; Miss Honey; and Grande-Maître Miss Sage (supervisor), Miss Snow, Chief Operator at Desk at the End of the Room. Photograph by Lt. Strohmeyer, Signal Corps, 10 January 1919. National Archives and Records Administration, 111-SC-46189. NARA ID # 86698547. GGA Image ID # 1990ceb2f2

Modern Signalers can relate to the challenges of deploying to a foreign land, often working with people they never met before being brought together by war. Once the planning, training, and preparation are done, and the equipment and personnel are underway, thoughts turn to how the team will manage to assemble the equipment, install it, and make it work.

Even if it does work, will it be scalable and grow fast enough to meet the demands of combat? Does the team have the expertise to make complex, fragile, and perhaps cutting-edge and experimental technologies work under austere conditions?

Everyone is counting on the Signalers and their technology, from the commanders and soldiers in the field to the logisticians to the intelligence and medical providers, and even your international and interagency partners.

So it was for Signalers when the US entered the Great War in 1917. The advanced communications technologies of that era were the telephone and the equipment infrastructure needed to connect thousands of users over long distances and challenging terrain.

The personnel required to install such a network included skilled cable splicers, linemen, heavy construction workers, test men, clerks, drivers, and mechanics. Once the equipment was in place, the speed with which calls could be connected and circuits maintained depended on the patience, nerve, and skill of the switchboard operators.

In 1917, women made up at least 80% of telephone operators employed in the US. Whatever their qualifications, however, women were prohibited by regulation from serving in the US Army.

As early as 1916, the US Army recognized that the scale and complexity of modern warfare demanded a rapid, reliable, and interoperable communications network that would require specialized expertise to acquire, install and operate. The War Department established a Signal Reserve comprised of such experts ready to respond during a national crisis.

The United States already had, relative to European countries, a vast, commercially-run telephone and telegraph network that connected all parts of the country. This network facilitated all economic, government-related, academic, and social transactions while the telephone companies invested in continuous improvement of the network's reach, capacity, and speed.

Army leaders likewise recognized the potential military advantages of direct telephone voice contact for command, control, and coordination of troops across long distances. They expected and demanded to fight by telephone.

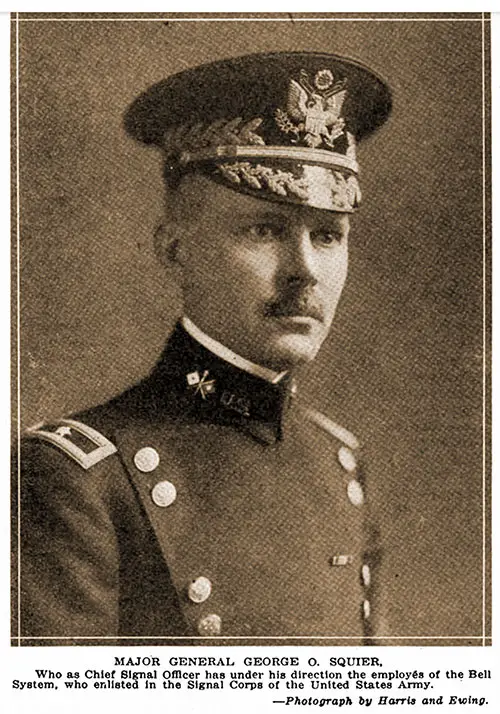

Major General George O. Squier. Who as Chief Signal Officer Has under His Direction the Employees of the Bell System, Who Enlisted in the Signal Corps of the United States Army. Photograph © Haris and Ewing. Bell Telephone News, January 1918. GGA Image ID # 19b3eda4b1

They were breaking from an Army tradition of filling Signal positions with men detailed from the ranks of the infantry, Maj. Gen. George Squier, Chief of Signal, built the Signal Reserve in close cooperation with American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T), Western Electric, Western Union.

He hand-picked the seed cadre for a force that would eventually grow to 56 field signal battalions, 33 telegraph battalions, 12 depot battalions, six training companies, and 40 service companies totaling 2,712 officers and 53,277 men. Signal units were called upon to replicate a telephone network of American scale, capacity, and reliability on French soil.

In cooperation with their French allies and industry partners, they built a massive network extending from the Atlantic coast to the American battle zone in France. This remarkable network comprised no less than 2,000 miles of pole lines, 28,000 miles of wire, and 40,000 miles of combat lines, interconnecting with French and British international circuits through 273 telephone exchanges plus numerous tactical switchboards throughout the combat zone.

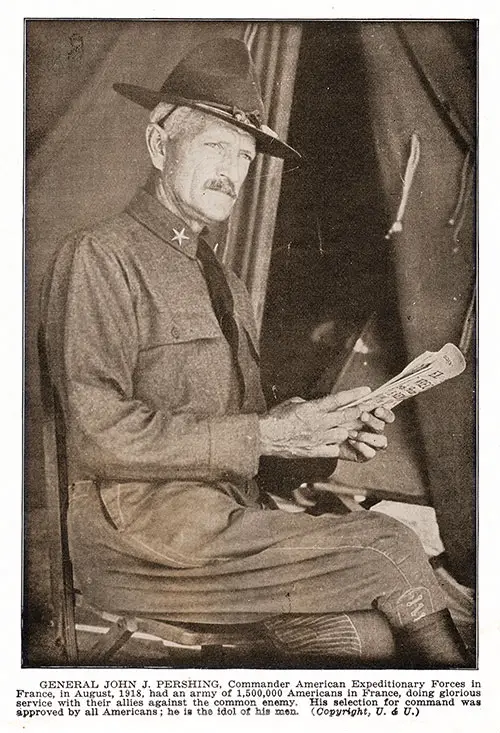

General John J. Pershing, Commander American Expeditionary Forces in France, in August, 1918, Had an Army of 1,500,000 Americans in France, Doing Glorious Service With Their Allies Against the Common Enemy. His Selection for Command Was Approved by All Americans ; He Is the Idol of His Men. The World's Greatest War, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18560e40f6

By November 1917, Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), had a vast communications infrastructure at his disposal. But soon, the demand for telephone calls across the theater of operations exceeded the ability of Army switchboard men to connect them quickly.

Success required far more than pure mechanical proficiency. The men often had to negotiate connections with French and British switchboard operators, who spoke with a different language or a strong accent and used protocols and procedures with which the Americans were unfamiliar.

Prioritizing military necessity over the Army's prohibition against women, Pershing cabled the War Department and wrote, "On account of the great difficulty of obtaining properly qualified men, request organization and dispatch to France a force of women telephone operators all speaking French and English equally well."

The War Department sent press releases to newspapers across the United States to recruit women willing to serve for the duration of the war and face the hazards of submarine warfare, aerial and artillery bombardment. These articles emphasized that patriotic women would be "full-fledged Soldier[s] under the articles of war" and would "do as much to help win the war as the men in khaki who go 'over the top.'"

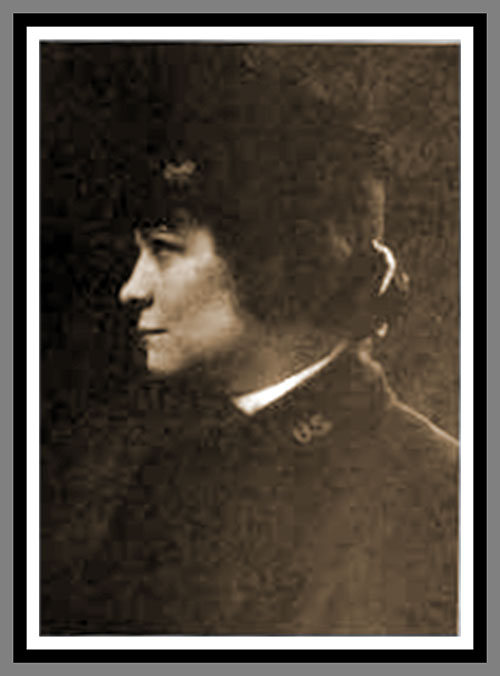

Grace Derby Banker, Chief Operator, US Army Signal Corps Telephone Units, France. GGA Image ID # 19b45199b2

Just as had happened when the call went out for technically qualified men to join the Signal Reserve, the response from women telephone professionals was overwhelming. More than 7,600 women volunteered for the first 100 positions. Grace Derby Banker from New Jersey and Inez Ann Murphy Crittenden from California were among the first recruits to be selected and take the Army oath in January 1918.

Inez Ann Murphy Crittenden (1897-1918) Chief Operator, US Army Signal Corps. GGA Image ID # 19b45d34a1

Hailing from opposite ends of the country, they had in common a unique blend of leadership, technical and linguistic expertise that Pershing was looking for. Like their male counterparts, they strongly desired to contribute their talents to the American war effort.

The Army appointed Banker and Crittenden to the rank of Chief Operator and selected them to lead the first and second units of bilingual telephone operators deployed to France in March 1918. They were the "Switchboard Soldiers," as Pershing referred to them, but more popularly known as the "Hello Girls."

As is a regular practice for the Signal Corps, most of the operators arrived before many combat units to provide communications support for the massive logistical operation of deploying the AEF. "The use of female telephone operators in France," according to the official report of the Chief Signal Officer, "was decided upon for two reasons.

The first of these was the unquestioned superiority of women as telephone switchboard operators… and the second was the desire to release for service in the more dangerous telephone centrals at the front, the male operators on duty in the larger offices."

Soon after the arrival of the Hello Girls, telephone service in France improved immediately, as calls tripled from 13,000 to 36,000 per day. Eventually, a total of six units of Hello Girls would deploy, bringing the number of calls per day to 150,000. When the war ended on November 11, 1918, 223 women operators served in France and collectively connected 26,000,000 calls for the AEF.

In recognition of their exceptionally meritorious service in the US Signal Corps during the Great War, the current Chief of the Army Signal Corps recently inducted Chief Operators Banker and Crittenden as "Distinguished Members of the Regiment" (DMR). Over a century ago, their lives and accomplishments exemplified some of the remarkable people in the history of the Signal Corps who led the Army's efforts to adapt during periods of rapid social and technological change.

Grace D. Banker trained as a switchboard operator with AT&T in New York City and later became a "long lines" (long-distance calls) instructor. As an expert switchboard operator and fluent French speaker with evident leadership traits, Miss Banker was chosen as the Chief Operator in charge of the first unit of women to sail for France.

She and her pioneering team were greeted on their first night in Paris by an aerial bombardment, followed later that day by German artillery rounds that continued to rain on Paris almost daily until the end of the war. Soon after the arrival in Paris of additional units of operators, Banker's unit of 33 women was split into three teams, with Banker leading 11 operators to support Pershing's headquarters in Chaumont sur-Haute-Marne, about 170 miles west of Paris.

Five months later, Col. Parker Hitt, the Chief Signal Officer of AEF's First Army, requested "French-speaking, excellent operators, in good physical condition" to support First Army Headquarters in Ligny-en Barrois, south of Saint-Mihiel. Miss Banker selected five more of the best operators to join her in moving to the forward command post on August 25, 1918.

Weeks later, they moved again with First Army headquarters to Souilly, near Verdun, remaining at their post despite the austere living and working conditions and being close enough to the battle to see the flash and feel the concussion of the guns.

After the Armistice went into effect on November 11, 1918, Miss Banker found peacetime duty in Paris at the temporary residence of US President Woodrow Wilson to be wholly unsatisfying. She wrote in her memoir, "We missed the First Army with its code of loyalty and hard work. We were back in the petty squabbles of civilian life..."

She opted for a position supporting the Army of Occupation in Coblenz, Germany until finally returning home nearly a year after the Armistice. As a testament to her extraordinary achievements, out of 16,000 eligible Signal Corps officers who served in the war, Miss Banker was one of just 18 to be awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

Thirty of her fellow operators received special commendations, Pershing signed many himself, for "exceptionally meritorious and conspicuous services" in "Advance Sections" of the conflict.

Crittenden led the second contingent of Hello Girls, which sailed for France just days after Miss Banker's group. Crittenden was well qualified for Army leadership due to her maturity, years of supervisory experience, expertise in speaking French, and her "commanding presence."

Once in France, she was frequently commended for her efficiency at running the Paris telephone exchange, providing translation, monitoring and relaying classified messages, and maintaining operational security of war plans. In a May 1918 letter to the Chief Signal Officer of the AEF, the Telegraph Officer supervising Crittenden stated, "I have left to her… almost the entire management of the Paris exchange and have caused her to reach out to our branch telephone exchanges in Paris, so that she may impress her personality upon the telephone operators employed in these different exchanges. We are improving our service every day through her efforts."

By August 1918, Director-General for Europe, American Committee on Public Information (CPI) recognized Crittenden's talents and her services requested in a by-name request. She served long enough in the CPI to be commended for her service but tragically lost her life on November 11, 1918, one of two women deployed with the Signal Corps who died in France in service to her country.

Both succumbed to the same influenza pandemic that killed more US Soldiers than died in combat.

Crittenden was buried with full military honors at the US Military Cemetery in Suresnes, outside of Paris. Yet the inscription on her headstone reads "Civilian." Like her fellow switchboard operators, the US government classified her as a contract employee rather than a Soldier.

Both Grace Banker and Inez Crittenden Were Posthumously Named Distinguished Members of the Regiment by the US Signal Corps. Army Communicator, November 2020. Image ID # 19b3be9157

This, even though they had never signed a contract, had taken the oath, wore uniforms with Signal Corps insignia and "dog tags," worked alongside military men. Nevertheless, and overriding the objections of Gen. Squier, the Army denied Signal Corps women the veterans' benefits granted male Soldiers, Army nurses, and even female Sailors and Marines who spent the duration of the war on US soil.

Finally, more than 60 years after the war, Congress passed legislation that retroactively acknowledged "the service of women who went to France during World War I as telephone operators for the US Army Signal Corps," the GI Bill Improvement Act of 1977 (Public Law 95–202; 91 Stat. 1433). The surviving Signal Corps telephone operators applied for and were granted status as veterans in 1979.

Although Banker and Crittenden have long since passed away, their recognition as "Distinguished Members of the Regiment" is significant not only for the current and future Signaleers inspired by their story but also for the direct descendants of the two women.

Based on Col. Linda Jantzen, "'Switchboard Soldiers' of the Great War," in Army Communicator, Vol. 2, Issue 12, November 2020.