Hello Girls of World War I

American Girls Serving in the Army Signal Corps As Telephone Operators in France, Colloquially Known As "Hello Girls." Signal Corps Colors Adorn Hats of These New Bilingual Wire Experts. Their Insignia, Too, Are Authentic and Terrifyingly Complicated. Armbands Indicate Rank. an Operator, First Class, Wears a White Brassard With a Blue Outline Design of a Telephone Mouthpiece. a Supervisor Who Rates With a Platoon Sergeant Wears the Same Emblem With a Wreath Around It. the Chief Operator or "Top." Has a Wreath, a Mouthpiece, and Blue Lightning Flashes Shooting out Above the Receiver—Which Is Most Appropriate for a Top. but the Top Says Those Jove-Like Lightning Flashes Don't Mean Anything. She Will Insist on Discipline if Required, but Thus Far, She Hasn't Had Any Occasion to Let Loose Thunderbolts at the Heads of Her Charges. No, As the Doughboys Do, the Girls Will Not Have the First Call at 6:15 and Reveille at 6:30. | GGA Image ID # 191e69a538

Introduction

The "Hello Girls" of World War I stand as a remarkable chapter in the history of military service and gender equality. These bilingual female telephone operators, recruited to serve in the Army Signal Corps, revolutionized battlefield communications. At a time when speed and precision were crucial, their ability to connect calls swiftly and efficiently proved invaluable to the American Expeditionary Forces. Despite their contributions under arduous and often perilous conditions, these women faced decades of denial regarding their status as veterans. This article chronicles their service, the recognition they eventually received, and their enduring legacy as trailblazers for women in the military.

History

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war against Germany. As a historically neutral nation, it was unprepared to fight a technologically modern conflict overseas.

The United States, in its time of need, turned to the American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) for support. The company was called upon to provide not only equipment but also trained personnel for the Army Signal Corps in France, a testament to its crucial role in the war effort.

AT&T executives in Army uniform served at home under the provisions of the National Defense Act of 1916, a crucial legislation approved on June 3, 1916. This act allowed for the induction of individuals with specialized skills into a reserve force, a key factor in the mobilization of resources for the war effort.

When General John Pershing sailed for Europe in May of 1917 as head of the American Expeditionary Forces (referred to in this section as the "AEF"), he took telephone operating equipment with him in recognition of the inadequacy of European circuitry and the understanding that telephones would play a key role in battlefield communications for the first time in the history of war.

From May to November of 1917, the AEF faced significant challenges in developing the telephone service necessary for the Army to function under battlefield conditions. These challenges included the need for rapid call connections and effective communication with French counterparts, as well as the slow connection rate of the average male operator.

Monolingual infantrymen from the United States could not connect calls rapidly or communicate effectively with their French counterparts to route calls over toll lines linking one region of the country with another.

The Army found that the average male operator required 60 seconds to make a connection. That rate was unacceptably slow, especially for operational calls between command outposts and the front lines.

During this time, telephone operations were largely sex-segregated in the United States. Hired for their speed in connecting calls, women filled 85 percent of the telephone operating positions in the United States. This was a significant shift from the male-dominated workforce, and it was found that the average female operator was able to make a connection in 10 seconds, a much faster rate than their male counterparts.

On November 8, 1917, General Pershing cabled the War Department and wrote, "On account of the great difficulty of obtaining properly qualified men, request organization and dispatch to France a force of women telephone operators all speaking French and English equally well."

To begin with, General Pershing requested 100 women under the command of a commissioned captain, writing that "all should have allowances of Army nurses and should be uniformed."

The War Department sent press releases to newspapers across the United States to recruit women willing to serve for the duration of the war and face submarine warfare and aerial bombardment hazards.

These articles emphasized that patriotic women would be "full-fledged soldier[s] under the articles of war." They would "do as much to help win the war as the men in khaki who go 'over the top.'". All women selected would take the Army oath.

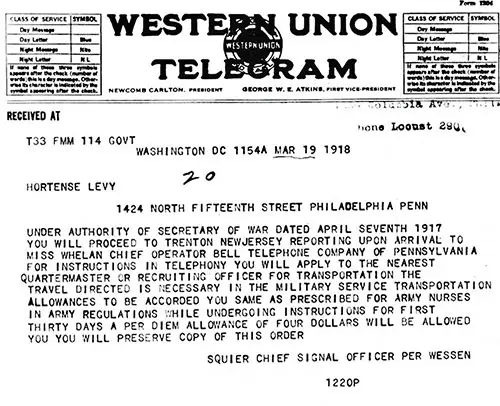

On 19 March 1918, Miss Hortense Levy of Philadelphia Received a Western Union Telegraph Instructing Her to Report for Training in Telephony, Also Known As Telephone Operation. WW1 Chief Signal Officer Major General George Owen Squier Later Cited Women's "Unquestioned Superiority" As Switchboard Operators and Their Value in Freeing Men for the Fighting Front. the Report of the Chief Signal Officer, 1919, Declared That "the Use of Women Operators Throughout the Entire War Was Decidedly a Success…". | GGA Image ID # 1976ea582e

Army Signal Corps Telephone Operator Miss Hortense Levy of Philadelphia Dressed in Uniform, Circa 1918. | GGA Image ID # 197756705a

A staggering number of more than 7,600 women volunteered for the 100 positions described above, and the first recruits took the Army oath on January 15, 1918, marking a significant moment in history.

In America, women primarily made up the workforce of civilian telephone operators. Nearly 10,000 women applied to fill Pershing's request. Those accepted into the program underwent a challenging selection process and made a profound decision to serve for the entire duration of the war, demonstrating their unwavering commitment.

The women were evaluated on tests similar to those of Army officer candidates. Then, the Secret Service conducted thorough individual investigations, underscoring the seriousness and rigor of the selection process.

The "Hello Girls" Group Was Standing In Front of a Building in France Circa 1918. Photograph by Bain News Service. Library of Congress, LCN 2014706868. | GGA Image ID # 191eb02ce8

Due to the sensitive nature of their work, the Army conducted more rigorous investigations into the loyalty and motivations of female Signal Corps members than the average soldier, highlighting the unique challenges they faced in their service.

These women were fully committed to their roles, undergoing daily military drills, learning about the Army, its traditions, and military terms, and adhering to uniform and rank regulations, demonstrating their unwavering dedication.

Like nurses and doctors at the time, female Signal Corps members had relative rather than traditional ranks. They were ranked as Operators, Supervisors, or Chief Operators. When promoted, the women were required to swear the Army oath again.

They were not just soldiers in appearance, but in every sense of the word. Their unique abilities overseas were a game-changer: They outperformed men in operating the military telephone and had an unparalleled proficiency compared to their British counterparts. Without the Hello Girls, the brigade of American troops would have been an impossible feat.

Of approximately 1,750 applicants, the Army trained 450 women, and 233 were ultimately sent overseas to serve as telephone operators. Colloquially dubbed "Hello Girls," these women were primarily stationed in England and France (and Germany after the Armistice was signed); some were stationed to work on the front lines in locations such as Saint-Mihiel and Souilly, France.

Typical Operating Unit at One of the Posts in France of the US Army Signal Corps Telephone Operators, 1918. | GGA Image ID # 1977c35d8e

Telephone operators, the trailblazers who were the first women to serve as soldiers in non-medical classifications, played a crucial role in helping win the war, not just mitigating its harms. They were affectionately known as the "Hello Girls" in popular parlance.

Signal Corps Operators, always in their Army uniforms and insignia, and with standard-issue identity disks in case of death, were not exempt from the military code. They were subject to court martial for any infractions, a testament to the seriousness of their role in the war effort.

Despite the military code's initial restriction to men's induction, the National Defense Act of 1916 marked a significant step towards gender equality. This act, which allowed for the induction of United States telephone industry members into the Armed Forces, imposed no gender restrictions.

Bilingual Telephone Operators Arrive in France

Four days later, on March 24, 1918, the first contingent of operators began their official duties in France. The operators arrived before most Armed Forces infantrymen to facilitate logistics and deployment. They spent their first night in Paris under German bombardment.

According to historian Rebecca Robbins Raines in Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the US Army Signal Corps, the first unit of female telephone operators to serve with the American Expeditionary Forces arrived in Paris in March 1918.

After the operators' arrival, telephone service in France saw an immediate and significant improvement, with the number of calls tripling from 13,000 to 36,000 per day.

Approximately 200 female telephone operators ultimately served in the First, Second, and Third Army Headquarters operating units.

The women, who were nicknamed the 'Hello Girls ', worked in Paris and dozens of other locations throughout France and England. They worked long hours, often under combat conditions, displaying remarkable bravery and dedication.

The Army quickly recruited, trained, and deployed five additional contingents of female Signal Corps operators. With this personnel, calls increased to 150,000 per day.

Group of American Telephone Girls on Their Arrival for "Hello" Duty in France. They All Can Speak Both English and French, March 1918. They Arrived Just the Other Day, and Like Everything Else, That's New and Interesting in the Army—Yes, They're In It. Too—They Were Lined up Before a Signal Corps Camera and Shot. Grouped About the Base of a Statue in a Little Paris Square, They Presented a Pleasing Sight. (American Girls Always Do.) The ladies of the Line Wear a Real Army Costume, Save That Their Campaign Hats Are Dark Blue and That They Have Shown Great Originality by Substituting the Skirt for the More Conventional O. D. Breeches and Putts. Their Hat Cords, Those Lovely Orange and White Things That the Signal Corps Wears (So Suggestive of Fillets of Orange Blossoms), Are the Real Tiling. So Are Their Buttons. And They've Got It on the Rest of Us in That They Know How to Sew on Those Buttons When They Come Off. National Archives Identifier 530718. | GGA Image ID # 191e57b026

Going beyond standard telephone operations, the bilingual Signal Corps members played a crucial role in bridging the communication gap between French and American officers. Their simultaneous translation services over the telephone were instrumental in ensuring smooth and effective communication.

There was a remarkable instance when the Army had to forcibly evacuate the Female Telephone Operators Unit of the First Army Headquarters. The reason? The women, despite their building being engulfed in flames, adamantly refused to desert their posts.

Upon readmittance to the building, the women, with their characteristic efficiency, restored operations within a mere hour. Their swift action and dedication earned them a commendation from the chief signal officer of the First Army. Grace Banker, a chief operator, was even awarded a Distinguished Service Medal for her wartime service.

Unbeknownst to the women operators and their immediate officers, the Army's legal counsel ruled internally on March 20, 1918. The women were not soldiers but contract employees, even though they had not seen or signed any contracts.

The Hello Girls in France Are Awaiting Inspection and Review by General Pershing. | GGA Image ID # 191e569806

The AEF fought their first major battles in the last two months of the war. By that point, the Signal Corps considered women's contributions so essential that, in telephone exchanges closest to the front line, the Army exclusively used women rotating 12-hour shifts. The Army established rotating 8-hour shifts in the rear, giving male soldiers the overnight shift when telephone traffic was slower.

WWI Chief Signal Officer Major General George Owen Squier later cited women's "unquestioned superiority" as switchboard operators and their value in freeing men for the fighting front.

The Report of the Chief Signal Officer, 1919, declared, "The use of women operators throughout the entire war was decidedly a success…"

Despite their invaluable service, the 'Hello Girls' returned home and were declared civilians, not military. This was a stark contrast to the recognition they deserved, but it did not diminish their spirit.

Although women served in a military capacity for the US Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard after the war, it was decided that technically only men could be members of the US Army.

In other words, while the Navy had opened enlistment to women during World War I, the Army did not. As a result, the Army did not consider the Hello Girls as servicewomen and did not issue honorable discharges.

Therefore, the 233 Hello Girls were not regarded as veterans of the war they had served in.

These female operators returned home after the war with little recognition and no veterans' benefits. It was a long and arduous journey, but only decades later, in 1978, did legislation finally award the operators the veterans' status they rightfully deserved.

Despite the regrettable lag in official recognition, proponents of the Army's gender integration during WWII often cited the Signal Corps' successful employment of the "Hello Girls."

These patriotic women took the same oath of allegiance as soldiers, received the same pay as soldiers, and wore the Signal Corps symbol. Serving with distinction, seven of these women were awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. One should note that upon their discharge, the 'Hello Girls" did not receive veteran's status or any of the benefits accompanying that designation.

In 1930, a fellow telephone operator named Merle Egan Anderson, inspired by the service of the Hello Girls, began her fight for the military benefits of US Army Signal Corps telephone operators. Her determination and perseverance are a testament to the strength of these women.

It wasn't until Congress passed the 1977 GI Improvement Bill, a significant piece of legislation aimed at improving benefits for veterans, that the 'Hello Girls' finally received government recognition for their service.

When President Carter signed the 1977 GI Improvement Bill into law, the 'Hello Girls' were discharged from the Military and granted Veteran benefits. These benefits included access to healthcare, pensions, and other support services. However, it's important to note that only 18 were still alive to receive these benefits.

Epilogue

Seven bilingual operators—

- The seven bilingual operators, famously known as the 'Hello Girls ', played a crucial role in the Battles of St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne. They served under the immediate command of General Pershing, their unique skills and dedication proving invaluable in these pivotal moments of the war.

- They staffed the Operations Boards with unwavering dedication, delivering orders to soldiers in the trenches, artillery units on alert, and pilots awaiting orders at French airfields.

- For their service in the Meuse-Argonne operation, the 'Hello Girls' were awarded a 'Defensive Sector Clasp', a testament to their bravery and dedication in the face of war.

- The Chief Operator supervising the Hello Girls, Grace Banker of Passaic, New Jersey, was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. Out of 16,000 eligible Signal Corps officers, Banker was one of only 18 honored individuals.

Thirty additional operators received special commendations, many signed by General Pershing himself, for "exceptionally meritorious and conspicuous services" in "Advance Sections" of the conflict.

The war ended on November 11, 1918. As of that date, 223 female operators served in France and had connected 26,000,000 calls for the AEF.

The Chief Signal Officer of the Army Signal Corps wrote in his official report two days after the date on which the war ended that "a large part of the success of the communications of this Army is due to … a competent staff of women operators.".

After the war ended, some women were ordered to Coblenz in Germany for that country's occupation and to Paris for the Paris Peace Treaty of 1919 to continue telephone operations, sometimes in direct support of President Woodrow Wilson.

Corah Bartlett and Inez Crittenden, two of these brave operators, died in France in the United States service. They were buried there in military cemeteries with full military honors, having succumbed to the same influenza pandemic that claimed more Armed Forces soldiers than combat operations.

The women of the Army Signal Corps were ineligible for discharge until formal release. Because of their logistics role, they were among the last soldiers to come home to the United States. The last Signal Corps operators returned from France in January 1920.

Upon arrival in the United States, the Army informed female veterans that they had performed as civilians, not soldiers, even though operators had served in Army uniform in a theatre of war surrounded by similarly engaged men.

Despite the objections of General George Squier, the top-ranking officer in the Signal Corps, the Army denied Signal Corps women the veterans' benefits granted to male soldiers and female nurses, such as—

- Hospitalization for disabilities incurred in the line of duty

- Cash bonuses

- Soldiers' pensions

- Flags on their coffins

- The Victory Medals promised them in France.

For the next 60 years, female veterans, led by Merle Egan from Montana, petitioned Congress more than 50 times for their recognition. In 1977, under the sponsorship of Senator Barry Goldwater, Congress passed legislation to retroactively acknowledge the military service of the Women's Airforce Service Pilots (referred to in this section as "WASPs") of World War II and "the service of any person in any other similarly situated group the members of which rendered service to the Armed Forces of the United States in a capacity considered civilian employment or contractual service at the time such service was rendered."

On November 23, 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed the legislation described above into law as the GI Bill Improvement Act of 1977 (Public Law 95–202; 91 Stat. 1433).

It wasn't until 1979, more than 60 years after their service, that the Signal Corps telephone operators, or the 'Hello Girls, 'were finally recognized as veterans, a long-overdue acknowledgment of their significant contribution to the war effort.

Only 33 operators who had returned home after the war were still alive to receive their Victory Medals and official discharge papers, which were finally awarded in 1979.

Olive Shaw, a Massachusetts native, returned to the United States after the war and worked on Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers's professional staff.

Shaw lived to receive her honorable discharge and was the first burial when the Massachusetts National Cemetery opened on October 11, 1980. Shaw's uniform is displayed at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri.

Upon receiving her honorable discharge at a ceremony in her Marine City, Michigan home, "Hello Girl," Oleda Joure Christides raised the paper to her lips and kissed it. The only thing Christides ever wanted from the Federal Government was a flag on her coffin.

On July 1, 2009, President Obama signed Public Law 111–40 (123 Stat. 1958), which awarded the WASPs the Congressional Gold Medal for their service to the United States.

The "Hello Girls" merit similar recognition for their role as pioneers who paved the way for all women in uniform and for service that was essential to victory in World War I.

Conclusion

The story of the "Hello Girls" is one of unparalleled dedication, resilience, and triumph over systemic challenges. Their critical role in securing effective communication during World War I exemplifies how ingenuity and commitment can transform the outcomes of war. Although their recognition as veterans came decades late, the acknowledgment serves as a testament to their enduring legacy. The "Hello Girls" paved the way for countless women in uniform, and their story continues to inspire as a symbol of perseverance, equality, and the vital contributions of women to national and global endeavors.

Bibliography

S.206 — 116th Congress (2019-2020), S.206 - Hello Girls Congressional Gold Medal Act of 2019, Sponsor: Sen. Tester, Jon [D-MT] (Introduced 01/24/2019) Committees: Senate - Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Latest Action: Senate - 01/24/2019 Read twice and referred to the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs.

"Hello Girls Here In Real Army Duds," in The Stars and Strips: Official Newspaper of te A.E.F., Paris, France, Vol. 1, No. 8, Friday, 29 March 1918, pp. 1-2.

Susan Thompson, CECOM Command Historian, "Hello Girls of World War 1," 27 March 1920. https://www.army.mil/article/234046/hello_girls_of_world_war_i Retrieved 26 March 1921.

Kenneth Holliday, "The Served: The 'Hello Girls' of WWI and their sixty-year battle for recognition, 30 March 2020. https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/72875/they-served-the-hello-girls-of-wwi-and-their-sixty-year-battle-for-recognition/ Retrieved 26 March 2021.

Women in World War I, National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/women-in-world-war-i.htm Retrieved 26 March 2021.