Steamships and Their Story

Front Cover and Spine, Steamships and Their Story by E. Keble Chatterton with 153 Illustrations, 1910. | GGA Image ID # 2056fca24c

Synopsis

This book provides, in a narrative free from technical terms, a complete history of the development of steamships, showing the evolution of the modern ocean greyhound from the earliest experiments in marine engineering. The illustrations form a unique feature of this handsome volume.

Contents

- Introduction

- The Evolution of Mechanically-Propelled Craft

- The Early Passenger Steamships

- The Inauguration of the Liner

- The Liner in her Transition State

- The Coming of the Twin-Screw Steamship

- The Modern Mammoth Steamship

- Smaller Ocean Carriers and Cross-Channel Steamers

- Steamships for Special Purposes

- The Steam Yacht

- The Building of the Steamship

- The Safety and Luxury of the Passenger

- Some Steamship Problems

List of Illustrations

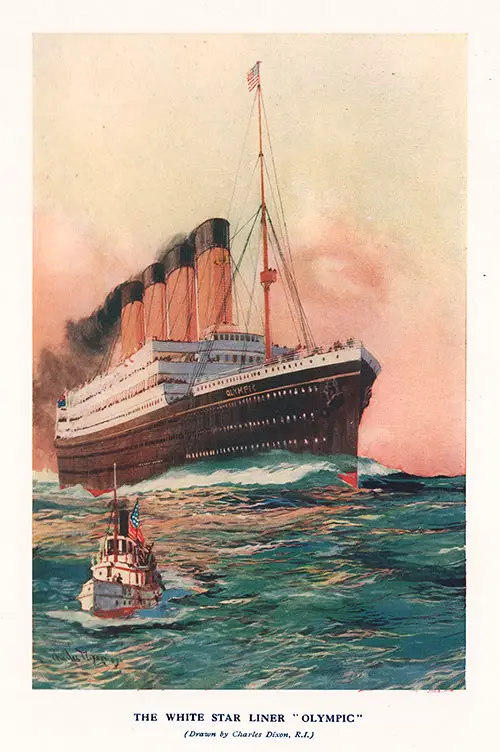

- The "Olympic"

- Hero's Steam Apparatus

- Jonathan Hulls' Steam Tug Boat

- The Marquis de Jouffroy's Steamboat

- Patrick Miller's Double-hulled Paddle-Boat

- Symington's First Marine Engine

- Outline of Fitch's First Boat

- The "Charlotte Dundas"

- The "Clermont" in 1807

- Fulton's design for a Steamboat submitted to the Commission appointed by Napoleon in 1803

- Fulton's First Plans for Steam Navigation Fulton's design of Original Apparatus for determining the Resistance of Paddles for the propulsion of the " Clermont," dated 1806

- The Reconstructed " Clermont " at the Hudson- Fulton Celebrations, 1909

- Paddle-wheel of the Reconstructed "Clermont"

- Fulton's Preliminary Study for the Engine of the "Clermont"

- Fulton's plans of a later Steamboat than the " Clermont-North-River," showing an application of the square side connecting rod Engine

- The " Comet "

- Engine of the "Comet"

- S.S. "Elizabeth" (1815)

- Russian Passenger Steamer (1817)

- The " Prinzessin Charlotte " (1816)

- The " Savannah " (1819)

- The " James Watt " (1821)

- Side-Lever Engines of the " Ruby " (1836)

- The " Sirius " (1838)

- The " Royal William " (1838)

- The " Great Western " (1838)

- Paddle-Wheel of the " Great Western "

- The " British Queen " (1839)

- The " Britannia," the First Atlantic Liner (1840)

- The " Teviot " and " Clyde " (1841)

- Side-lever Engine

- Launch of the "Forth" (1841)

- The " William Fawcett " and H.M.S. " Queen (1829)

- Designs for Screw Propellers prior to 1850

- The "Robert F. Stockton" (1838)

- The "Archimedes" (1839)

- Stern of the " Archimedes "

- The " Novelty " (1839)

- The "Great Britain" (1843)

- Propeller of the " Great Britain "

- Engines of the " Great Britain "

- Engines of the " Helen McGregor "

- The " Scotia " (1862)

- The " Pacific " (1853)

- Maudslay's Oscillating Engine

- Engines of the "Candia"

- The "Victoria" (1852)

- The " Himalaya " (1853)

- Coasting Cargo Steamer (1855)

- The " Great Eastern " (1858)

- Paddle Engines of the " Great Eastern "

- Screw Engines of the " Great Eastern "

- The " City of Paris " (1866)

- The " Russia " (1867)

- The " Oceanic " (1870)

- The " Britannic " (1874)

- The " Servia " (1881)

- The " Umbria " (1884)

- The " Orient " (1879)

- The " Austral " (1881)

- The " Victoria " (1887)

- The " Majestic " (1889)

- The " City of Paris " (1893) (now the " Philadelphia ")

- The " Ophir " (1891)

- The " Lucania " (1893)

- The " Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse " (1897)

- The " Oceanic " (1899)

- The " Cedric "

- The " Celtic "

- The "Kaiser Wilhelm II."

- Giovanni Branca's Steam Engine (1629)

- The Blades of a Parsons Turbine

- The Parsons Turbine

- The " Carmania " (1905)

- Lower half of the fixed portion of one of the " Carmania's " Turbines

- A Study in Comparisons : the " Magnetic " and "Baltic"

- The " Mauretania " when completing at Wallsend-on-Tyne

- Stern of the "Mauretania"

- The " Lusitania "

- The " Adriatic "

- The " George Washington "

- The " Berlin "

- The " Laurentic " on the Stocks

- The " Mooltan "

- The Starting Platform in the Engine Room of the " Mooltan "

- The " Balmoral Castle "

- The " Cambria " (1848)

- Engines of the " Leinster " (1860)

- The "Atalanta" (1841)

- The " Lyons " (1856)

- The " Empress " leaving Dover Harbor

- The Ocean Tug " Blackcock "

- The Passenger Tender " Sir Francis Drake "

- The 7,000 ton Floating Dry-dock under tow by the " Roode Zee " and " Zwarte Zee "

- The Salvage Tug " Admiral de Ruyter "

- The New York Harbor and River Tug Boa " Edmund Moran "

- The Paddle-Tug "Dromedary"

- The Bucket Dredger " Peluse "

- The Suction Dredger " Leviathan "

- The " Vigilant "

- The Telegraph Steamer " Monarch "

- Deck View of the Telegraph Ship " Faraday "

- The " Silverlip "

- Section of Modern Oil-Tank Steamer

- The Turret-ship " Inland "

- Midship Section of a Turret-ship Cantilever Framed Ship

- The North Sea Trawler " Orontes "

- The Steam Trawler " Nôtre Dame des Dunes "

- Hydraulic Lifeboat

- A Screw Lifeboat

- The " Inez Clarke "

- The " Natchez " and the " Eclipse " (1855)

- The " Empire "

- The " Commonwealth "

- Beam Engine of an American River Steamer The " City of Cleveland "

- An American " Whale-back " Steamer

- Typical Steam Yacht of about 1890

- A Steam Yacht of Today

- The Russian Imperial Yacht " Livadia "

- The Royal Yacht " Victoria and Albert "

- The Royal Yacht " Alexandra "

- The S.Y. "Sagitta"

- The S.Y. " Triad "

- " Flush-decked " Type

- " Three Island " Type

- " Top-gallant Forecastle " Type

- " Top-gallant Forecastle " Type, with raised quarter-deck

- Early " Well-deck " Type

- " Well-deck " Type

- " Spar-deck " Type

- " Awning-deck " Type

- "Shade-deck" Type

- The Building of the " Mauretania " (showing floor and part of frames)

- The " George Washington " in course of Construction

- Bows of the "Berlin" in course of Construction

- The " Berlin " just before her Launch

- Stern frame of the " Titanic," February 9, 1910

- The Shelter Deck of the " Orsova " in course of Construction

- One of the Decks of the " Lusitania " in course of Construction

- Launch of the " Araguaya "

- Launch of a Turret-Ship

- The " Suevic " ashore off the Lizard

- The Stern Part of the " Suevic " awaiting the New Bow at Southampton

- The New Bow of the " Suevic " at the entrance to Dock

- Charles Dickens's State-room on the " Britannia"

- The Veranda Café of the " Lusitania "

- First Class Dining Saloon of the " Adriatic "

- Dining Saloon of the S.Y. " Liberty "

- Gymnasium of the S.Y. " Liberty "

- The Marconi Room on a Cunard Liner

Color Illustration of the White Star Liner Olympic, Drawn by Charles Dixon, R.I. Steamships and Their Story, 1910. | GGA Image ID # 2057007a40

Review of Keble Chatterton's "Steamships and Their Story"

Following up his success in Sailing Ships and Their Story, Mr. Chatterton writes—in a sumptuous volume with one hundred and fifty-three illustrations, the print and get-up of which is a delight— the history of the steamship on similar lines.

The story is clear and interesting, and it is pursued with enthusiasm and merciful avoidance of technicalities. Indeed, the lay reader can run and not grow weary while obtaining (as the author promises) a fair grasp of the principles that underlie the building and the working of a ship.

One need not abandon hope even when he enters the engine room door. The author has, it would seem, surveyed every aspect of the subject. There are chapters on the steam yacht, steamships for particular purposes like freighters and trawlers and whalebacks, and inland and cross-channel and P. and O. ships—as well as of the big North Atlantic liners, an abstract given below.

Around the sailing ship, says the author, there hovers eternally the halo of romance. Still, in her eight thousand years of recorded history, she has not done more for the good of humanity than the steamship within less than a century.

And she is equally romantic, for she is as nearly human as anything in the world can be, which is not. It is a fitting time to write her history, for much further than a forty-five-thousand-ton ship, it cannot be possible to go.

The Chinese had long worked at the idea of propelling a boat by machinery; the Romans had at least attempted it; the Middle Ages had tried it also, but in the seventeenth century, Solomon de Caus published a treatise on the application of steam as a means of elevating water, and at the beginning of the eighteenth Papin determined to propel a ship by it.

The paddle wheel turned by physical force was thoroughly grafted into man's mind long before he thought of the steamboat, for no one dreamed of utilizing steam as long as human labor was too cheap to bother about it.

The propelling energy of steam was noted as early as 130 B. C., but to Papin, in 1707, belongs the honor of constructing the first steamboat— which he navigated on the River Fulda in Hanover. But the local boatmen smashed her to pieces, and he barely escaped with his life.

It took the engines of two inventors to make a Watts, to devise a separate condenser and an air pump, and to hit upon some method of converting the vertical movement into a rotary one.

With Watts's engine, two Frenchmen, Périer and De Jouffroy, experimented for marine application. The latter succeeded at Lyons in the presence of ten thousand witnesses. But he was compelled to fly for his life in the French Revolution.

Before obtaining a patent, he was forestalled by others experimenting in England and America. In 1786, Fitch produced a boat with a speed of eight miles an hour and ran regularly on the Delaware, covering over two thousand miles during the summer of 1790.

So it is not to be wondered at that, bitterly disappointed at his shareholders' lack of faith, he committed suicide. In praising Fulton, we have kept the recognition he deserves from Fitch.

Still, another man achieved a practicable steamboat before Fulton, a Scotchman in a steam tug called the Charlotte Dundas. It was from the Frenchman, I'érier, that Fulton borrowed the engine for his boat; unlike some of his admirers, he never showed the slightest disposition to deny his indebtedness to what others had done before him.

The previous failures, he believed, were due not to defective engines but to wrong methods of applying the steam. With his second boat, the Clermont, we step from the realm of theories and suggestions into a realm of almost uninterrupted success.

But it was absolutely—as he testified—a success in which many men had taken part, both by their failures and their achievements, and practically no part of the Clermont was his invention. It was his manner of employing the parts scientifically that made him succeed.

The Dean of Ripon, who was on the Clermont during her first voyage, prophesied that steam vessels might even be able to cross the Atlantic before the end of the nineteenth century. Fulton lived to see the first vessel tempt the ocean, for Stevens—driven off the Hudson by the court's decision to grant Fulton the monopoly thereon—took his boat round to the Delaware by sea.

With the Comet began the activities of the Clyde manufacturers and continued for some time unrivaled, for the watermen on the Thames were more successful than they had been on the Hudson in their opposition to the new craft. In her twenty-one days of sea voyage, the Savannah of New York exhausted her coal in eighty hours' steaming and had to fall back on her sails.

But by the third decade, the Enterprise, on a voyage from London to Calcutta, steamed for one hundred and three days out of her total of one hundred and thirteen.

When the Great Western crossed the Atlantic in fifteen days with only one-fourth of her coal consumed, people saw it paid to build a vessel big enough to carry plenty of fuel. Her fare was thirty-five guineas, and her largest number of passengers was one hundred and fifty-two. She averaged eight knots a day, but the British Queen, who followed her, averaged ten.

The many successes of this year. 1838, set a prominent merchant of Halifax to thinking. So when the Admiralty invited tenders to carry the American mail by steamboat, he crossed to London, where he was unsuccessful in raising capital, and then to Glasgow, where the Scotch proved more foresighted. Lie eventually got the contract, and the Cunard line was begun. Its history is practically the history of the American liner.

Not until 1852 did the Cunard company give an iron ship with a screw propeller a trial. Iron and screws had been fighting their way all this time, for both of the new nicas brought in a new set of problems which it took many experiments to solve.

The increased length of the ships compelled iron, so it won out despite virulent opposition. Rut the screw propeller was much objected to by the saloon passengers—who, according to medieval custom, still had the place of honor in the stern—on account of the vibration.

Propellers had the start of paddles in America for three years before Fulton came on the Hudson Stevens, who took his boat over to Delaware by sea. He had crossed the river from Hoboken to New York in a craft propelled by a double screw.

But, it remained for the Great Rastern to demonstrate in the face of the passengers' objections that the paddle wheel was unsuitable for ocean work. In addition, she showed the advantage of the double bottom, for she ran on a rock and damaged more than one hundred feet of her outer hull, yet completed her voyage without leakage into her hull correctly.

These two things were perhaps service enough for any one ship. Indeed, she did little else, for she was a monster born before her time. Not until a half-century later did builders have enough experience for such a large ship. It took three months to persuade her to enter the water after she was built; when she got there, she could not pay her way, and after laying the Atlantic cable, she was handed over to the ship breakers.

The use of iron meant a saving in displacement of about one-third. The ship could have a much thinner skin and thus carry more cargo, and it was possible now to control a fire started at sea. Regarding the two innovations, the Inman line preceded the Cunard.

It inaugurated, too, the custom of carrying steerage passengers—who before had traveled solely on sailing ships; and it abolished the long, narrow, wooden deckhouse to give the passenger's promenade room. Then, the White Star ship, the Oceanic, threw convention to the winds and established a new order.

Her beam was exactly one-tenth of her four hundred and twenty feet length; she substituted iron railings for the usual heavy, high bulwarks, which gave false security in that they did not allow a shipped sea to run off; she added another iron deck; she placed her saloon passengers forward, where they would feel the vibration least and instituted many devices for their comfort, notably oil lamps for candle lamps and revolving saloon armchairs.

Finally, she broke the record for speed. But she did not hold the new one long, and the Guión line steamer Oregon won the blue ribbon; she was first called "the greyhound of the Atlantic." In the Senna, steel replaced iron, which is now not used in ship construction. It proved another weight-saving and so permitted greater cargo and more powerful engines.

Seeing all this brisk competition, the Cunard company began to bestir itself. So well had she profited by all these experiments of others that her new boats, the Umbria and the Etruria, actually increased their speed with age, and though they were afterward much outdistanced, they continued to make records in endurance and emergency tests.

But again, the Cunard line left to another the introduction of an innovation. The Inman company, which had put out the first successful screw liner, was the pioneer of the twin-screw boats in New York and Paris, afterward taking over into the new American line. Once the twin screw was established, the ship became independent of auxiliary sails, and they disappeared from the liners.

Now began the period when the latest steamship so quickly becomes obsolescent that it is swiftly handed over to another hemisphere or to the ship breakers before the general public has ceased to marvel at its improvements and luxuries.

Competition, already fierce, was increased by the entry of Germany into the list. Her rapid development in shipbuilding is a phenomenon. It dates, like her other industries. Only from the close of the Franco-Prussian War, yet in 1807, with the Kaiser Wilhelm der Crasse, did she take over the blue ribbon of the Atlantic. The British replied with the White Star Oceanic, not in speed but in size.

She was comparatively slow but more efficient in proportion to expense, with five whole decks and two partial ones. The Cunard, satisfied with the speed of her express steamers Campania and Lucania, began to build "intermediate'' ships for comfort and economy of passage rather than brevity.

The White Star followed her lead, but the Germans pursued the speed idea and again broke all the Kaiser Wilhelm II records. She paid two hundred tons of extra fuel a day for her extra knot over her sister ship.

The most beautiful period of the steamship has just opened with the inauguration of the turbine. "It marks a distinct cleavage between yesterday and tomorrow."

In its simplest form, the turbine is similar to a water wheel, with a jet of steam taking the place of water. It was suggested as far back as 1629 by an Italian engineer.

The Cunard company, as usual, left to another, the Allan Line, its introduction upon the Atlantic, but they adopted it in the Mauretania and the Lusitania. The new engine allowed them to fill their conditions in terms of size and running economy and win back the coveted blue ribbon for speed.

But this—even with so wealthy a corporation—was only done as a move in the Great British War game with Germany, for it could not have been accomplished except by the government's financial assistance, which advanced one-half of their total cost.

Of their colossal proportions, it is hard to get any idea. But these leviathans are outclassed by two ships building for the White Star, which—it is said—arc to lie fitted with roller-skating rinks and will necessitate dredging the harbors to a depth of thirty-five feet.

Future contracts seem to show that the economy of running plus first-class service is now being sought after rather than speed, and ship-builders can already turn out a monster one thousand feet in length.

As for luxuries, the "profoundly preposterous box" which Charles Dickens called his cabin in 1842 has grown into an exceedingly comfortable apartment, while the millionaire may hire a regal suite with bedrooms and dining rooms, fireplaces, mirrors, sconces, and the rest, as perfect as in the most extravagant metropolitan hotel.

"Safeguard" is spelled out in every detail; thermostats, submarine bells, engine-room telegraphs, and wireless telegraphy ensure the passenger better on the sea than on land in his home. And still, the problems of the steamship—not only technical ones, but those of commissarying and ventilating— have not all been solved.

But with telephones, Turkish baths, gymnasia, newspapers, veranda cafés, meals à la carte, fish tanks, and hospitals—what else is left to the ingenuity of man to devise for the pampered passenger? Who stood on the Clermont deck could ever have imagined it?

Algernon Tassin, Review of Edward Keble Chatterton's "Steamships and Their Story," London-New York: Cassell Company Ltd., 1910, in The Bookman: A Magazine of Literature and Life, Vol. XXXII, No. 1, September 1910, pp. 296-299.

Library of Congress Catalog Listing

- Personal name: Chatterton, E. Keble (Edward Keble), 1878-1944.

- Main title: Steamships and their story, by E. Keble Chatterton ... With 153 illustrations.

- Published/Created: London, New York, Cassell and Company, Ltd., 1910.

- Description: xx, 340 p. col. front., illus., plates. 25 cm.

- LC classification: VM615 .C6

- LC Subjects: Steamboats. Shipbuilding.

- LCCN: 10024773

- Other system no.: (OCoLC)2046170

- Type of material: Book