History of the 351st Infantry, 88th Division, AEF

Reveille is Blown

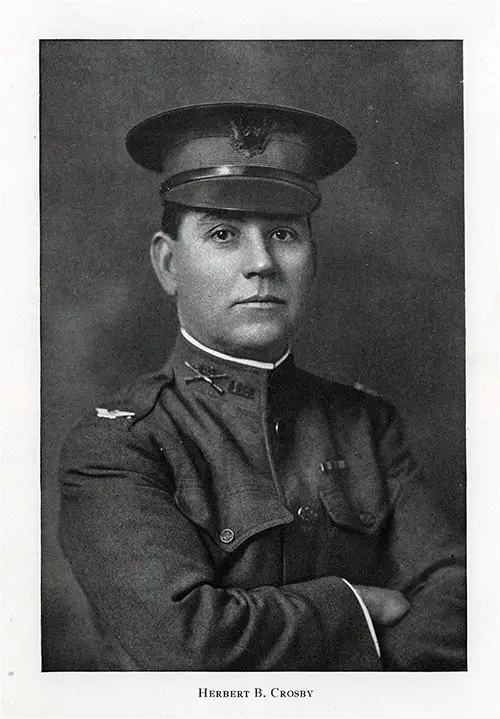

Colonel Herbert B. Crosby of the 351st Infantry, 88th Division, AEF

WHEN war, armies, registration and a few other predominant questions of the time were decided in Congress in 1917, and the then called National Army finally got under way, it was Des Moines, a fair city near the center of Iowa, which became one of the great Yank meccas in the United States.

It was in June of that year that the site was selected and the construction work started on what became known as Camp Dodge. Camp Dodge owed its selection almost wholly to its geographical location.

It was centrally located with regard to Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois, North Dakota, South Dakota, Kansas, Nebraska, and Missouri—states which furnished men to make up the Division which was trained at that point.

Before the dust of the cornfields on which the camp was situated was given time to settle and cake, and before the two-story frame buildings were all completed, the first of the new army began to arrive- first, officers from the regular service and the training camps—and a few days later the cosmopolitan gathering which was eager to assimilate the intricacies of the “Infantry Drill,” get uniforms and be soldiers.

On the 29th of August, 1917, the 88th Division sprang, full grown into being, and by September 3rd, the preliminary work of organization had been completed, and the Division was ready to receive its quota of the men of the north and central west. Major General E. H. Plummer was assigned to command the Division. Brigadlier General William D. Beach was assigned to the 176th Brigade, and Colonel Herbert B. Crosby to the 351st Infantry.

Shortly after the organization of the Division, the regiment was organized, and officers were assigned as follows:

Captain Russell B. Rathbun was appointed regimental adjutant.

Lt. Colonel James F. McKinley and Major Leonard W. Prunty were assigned to and joined the regiment on August 30, 1917.

Headquarters Company: Capt. Henry I. Church, 1st Lt. George L. Stocking, 1st Lt. Varro E. Tyler, 2nd Lt. Ben H. Johnson.

Supply Company: Capt. Harry E. Freese, 1st Lt. Carl J. Zobel.

Machine Gun Company: Capt. Constantine V. Schmitt, 1st Lt. Herbert A. Metzger, 1st Lt. Paul Lehn, 2nd Lt. Frank M. Potter, 2nd Lt. Rufus W. Scott.

Company "A": Capt. Walter M Willy, 1st Lt. Charles F. Stone, 1st Lt. Angus G. Grant, 2nd Lt. Charles H. Kelley, 2nd Lt. Arthur W . Furber.

Company "B": Capt. Joseph O. Hay, 1st Lt. Howard A. McCandless, 1st Lt. Charles R. Chinn, 2nd Lt. Limer L. Berg, 2nd Lt. Vernon W. Carris.

Company "C": Capt. Charles W. Blanding, 1st Lt. Arthur A. Emley, 1st Lt. William W. Cheyne, 2nd Lt. Frank L. Hixenbaugh, 2nd Lt. Lawrence W. Helgeson.

Company "D": Capt. Robert P. Robinson, 1st Lt. Frank B. Patterson, 1st Lt. Charles T. John, 2nd Lt. Edward F. Kovar, Jr., 2nd Lt. James H. Taylor.

Company "E": Capt. Adam Richmond, 1st Lt. Verne Miller, 1st Lt. James A. Robson, 2nd Lt. Carleton M. Magoun, 2nd Lt. Earl H. Erp.

Company "F": Capt. John A. Jimerson, 1st Lt. Joseph Lees, 1st Lt. Harry G. Carpenter, 2nd Lt. William E. Mitchell, 2nd Lt. Ralph L. Stevens.

Company "G": Capt. Frank O'Leary, 1st Lt. Russell D. McCord, 2nd Lt. Carl W. Smith, 2nd Lt. James R. Murphy.

Company "H": Capt. Frederick C. Legg, 1st Lt. Whitney Wall, 2nd Lt. Mathew H. Lynch, 2nd Lt. Carl W. Painter.

Company "I": Capt. Chas. O. Bunner, 1st Lt. Frank W. Carpenter, 1st Lt. Russell L. Park, 2nd Lt. Henry C. Harper, 2nd Lt. Joseph Boyd.

Company "K": Capt. Harry F. Evans, 1st. Lt. Emmet S. Harden, 1st Lt. Walter Pratt, 2nd Lt. Norris S. Stoltze, 2nd Lt. Mathew D. Eckerman.

Company "L": Capt. Ralph M. Douglass, 1st Lt. Melvin Uhl, 1st Lt. Charles R. Stafford, 2nd Lt. Carroll B. Martin, 2nd Lt. Harry Slaughter.

Company "M": Capt. Rodney S. Dunlap, 1st Lt. Carl J. Judson, 2nd Lt. Robert F. Gantt, 2nd Lt. Elmer R. Bullis

To complete the complement of officers, the following named officers were attached to the regiment and were attached to companies as follows:

Headquarters Company: 2nd Lt. Robert F. Schuck, 2nd Lt. Paul F. Schlick.

Machine Gun Company: 2nd Lt. Paul V. Ohlheiser.

Company "A": 2nd Lt. Alfred Teisberg.

Company "B": 2nd Lt. Homer R. Dodsley.

Company "C": 2nd Lt. Edmund H. Booth.

Company "D": 2nd Lt. Morton Hiller.

Company "E": 2nd Lt. Frank A. Darling.

Company "F": 2nd Lt. David M. Williams.

Company "G": 2nd Lt. A. C. Fedderson, 2nd Lt. Linn Culbertson.

Company "H": 2nd Lt. Irving W. Benolken, 2nd Lt. Clarence A. Maloney.

Company "I": 2nd Lt. Frank J. Bowen.

Company "K": 2nd Lt. Leo R. Geynor.

Company "M": 2nd Lt. Rix H. de Lambert, 2nd Lt. Walter F. Day.

On September 3, 1919 the Medics reported, pursuant to S. O. No. 10, Headquarters, 88th Division, the detachment at that time being:

1st Lt. Frank R. Borden, 1st Lt. Elmer P. Blankenship, 1st Lt. Aubrey K. Brown, 1st Lt. Carl L. Brimi.

Three days later, September 6th, the men began to arrive, five per cent reporting September 6th, forty percent came two weeks later, and by September 21st, the regiment was assuming proportions, and the work of whipping the machine into shape began.

The regiment was made up of men coming from the four northwest counties of Iowa, and that part of Minnesota, including the city of St. Paul, that lies south of the Minnesota River.

A cosmopolitan crowd, whose first question was one of something to eat and a uniform, and whose real trouble was to determine whether or not salutes were in order, and il they were how to do it.

At that time the plumbing system of the camp wasn't running as serenely as it might have, and there was a unanimous verdict that the government had picked out the hottest and dustiest place in America for a camp, and getting dirt out of ears was the most perplexing job the new soldier had.

Getting Ready

Alter a week, everybody had a campaign hat, O. D. shirt, belt and russet shoes, issue, and the company streets became active with squads righting, and parade resting— without arms. Ambitious candidates tor corporals’ jobs spent long hours at night with the I. D. R., and next day wondered what command it took to make some ordinary private face about; but by the middle of October sergeants' and corporals’ chevrons were being sported -- old issue “Krage” were doing duty at "present” and “port arms,” and the regiment was beginning to wonder it it was ever to be sent overseas. By this time leggings, breeches, O. D, and blouses had been signed for.

Then in late October the e4th Division at Camp Cody and the 35th Division at Camp Doniphan sent out a call and 500 men of the regiment were sent. The squads were broken up a bit, the company lines made a trifle shorter, but the work went on until November 20th, when 1500 men were sent to Camp Pike to the 87th Division, leaving from 12 to 18 non-commissioned officers, including the 1st sergeant, in each company.

Winter was on—coal had to be gotten, K. P. to be done, and no privates— so from the old-time 1st sergeant to the youngest corporal in the outfit, everybody sailed in and from handling coal, doing K. P., keeping the fires going, doing two on, four off, and later, when the thermometer got down to 20 below—the running guard—to making out fatigue details in the orderly room, with an occasional Saturday night in Des Moines—the winter was passed until February.

Then the non-coms began to press up the O. D., hitch up their belts and snap into things a little more soldierly—for the new men were coming in. The regiment received its quota—only to lose them again in March when they, with a large number ot the old non-commissioned officers, were sent overseas. Again in March and April men came in — only to go on.

It was at this time that Major Prunty was called from the regiment to duties in Washington. The men of the regiment reluctantly saw Major Prunty leave—for he was the friend of all—and the impression he made remained with the regiment throughout its existence.

Port of Embarkation

In May, Missouri and Kansas sent their contingent to Dodge and the sound of the schedule and the intensity of the work -- everybody sensed that: “Well, we’re on our way for sure.” Reveille came before sun-up and taps long after dark and the drill field, rifle range and gas house were working overtime.

Equipment came—and was issued—and inspections were made to see that none was lost. It it was, less pay next month. Records were brought up to date; officers and non-commissioned officers worked all day and smoked and worked and cussed half the night. Then, in late July, entraining orders for a place only the War Department knew, came. On the 5th of August Company M, the last company of the regiment to leave, got aboard, were pulled out on to the main line, and woke up the next morning in Indiana—headed for the coast.

Three days later the regiment was again assembled in tents at Camp Mills, L. I., where the final inspections were passed and the last wind and rainstorm experienced, and the peaked fedora campaign hat swapped for “Old Rain-in-the-face.”

On the morning of the 16th the ride to the docks was taken, the "latest" passenger list dug up, and the single file up the plank begun. After that— the assignment to a hammock, issue of a life-belt, a speedy inspection of H. M. S. something or other, and then to the decks to kid some M. P. who wasn’t going along.

Lt. Col. McKinley was lost to the regiment shortly before it sailed—and the regiment lost another friend who is remembered by those who knew him.

When the steamships Saxon, Scotian, and Ulysses left their docks at Hoboken at 12:5.5 p. m., carrying 3500 American soldiers of the regiment, and poked their bows, covered with cheering France-bound warriors, down the river and toward open sea, the regiment bade goodbye to the sun-swept shores of America.

Looking for the Worst

To the bulk of those aboard, the trip so far had been a sight-seeing expedition, for all were westerners and not all had had an opportunity of visiting the East. So, after the transports had pushed off, got under their own steam and joined the convoy, aft and mid decks were crowded, for the New York skyline and the Statue were becoming dimmer with every turn ol the propeller, and shortly memories alone remained.

Sixteen transports were in the convoy along with the cruiser St. Louis and some destroyers. The first day a seaplane and dirigible escorted the convoy, as the waters outside the harbor were sub-infested, there being a ship sunk there the day before.

The sea was unusually quiet and aside from the zigzag course that was being taken, lifeboat drill, trying to make the inner man keep quiet on British rations, and the usual stand of guards, there was nothing unusual in the trip—until the night when an iceberg was sighted and all the artillery in the world took a shot at it.

A northerly course had been taken and the fogs of Newfoundland and chilly weather were encountered. After eleven days, news leaked around that we were getting into the Irish waters and where the U-boats were particularly active.

The boat crews said that at eight next morning the mosquito fleet would “pick us up,” and promptly at eight that morning specks appeared all about the convoy through the mist, and ten minutes later a fleet of British destroyers were playing hide and seek around and among the boats of the convoy.

At nine that morning trouble started—- something had been discovered by H34— who promptly dropped a depth charge. The convoy avoided the H34 and the circle she was cutting around a particular spot on the sea, and nobody saw what really was happening, and nobody ever found out, yet in an hour the H34 came rolling along and joined the others.

Officers who Came Overseas With Regiment

Europe

Anchor was dropped the night of August 27th and on the morning of the 28th packs were rolled, hard tack and willie issued, the companies assembled and roll called and all lined up for disembarking.

Once ashore, legs were tested and the absence of the “sailor’s roll’’ or “sea legs” was a disappointment. Then somebody asked a British woman where we were and the word “Liverpool” went down the line.

After a short rest at docks, the command to fall in was given, everybody counted off, did squads right, and started for the train sheds. The first call down in England came from a British cop who told the leading company to get over on the left side of the street.

Travel was made in third-class English coaches—a striking contrast to the American means of travel. Yet this inconvenience was made light of.

The regiment was fortunate in being able to travel across the Island during daylight, and England at that season was, as one buck in Company B said: “Gawd-a-mighty, they’ve just mowed the grass, and sprinkled the lawn.”

Late in the afternoon the regiment arrived at Brookwood, a suburb of London, in the Aldershot Training Area. Billets were in tents and Stoney Castle the name of the camp. The Third Battalion was stationed at Cowshott, an auxiliary of Stoney Castle.

During the four days the regiment was in the area, many acquaintances with the British, and with the Australians in particular, were made. The ‘‘Hi, there, Yaynk, hoos yer lidy friend?” of the Australians remains one of the cheerful memories of the war, for the Australian, as he was seen, was an American with a funny dialect.

At six-thirty the morning of September 3rd, packs were rolled and the regiment entrained at Brookwood, leaving the train at ten-thirty a. m. at the docks of Southampton. Transportation failed to appear and the regiment hiked to Camp Church on the outskirts of Southampton, where billets in barracks were drawn.

It was here that men of the regiment became rather well acquainted with the British young woman, for some enterprising private in the Headquarters Company found out that the old time kissing games were quite the rage in England; so, while the Welch Guards’ Band furnished the music, a good many of the benedicts of the regiment established a rather enviable reputation.

France

On the evening of September 5th the regiment got aboard several small boats and started across the Channel. More real sea was experienced in those twelve hours than had been experienced in the previous twelve days, and not a few spent their time in feeding their piscatorial pals.

However, daylight brought the cherished sight of the shores of France it also brought the rain with which the regiment was to become so familiar.

A hike to another rest camp was made where the night was spent and the next afternoon brought another hike and our first introduction to the French Premier Class of traveling box cars 40 hommes or 8 cheveaux.

For scarcity of room and rough riding qualities, the 40 hommes and "Wheet" cheveaux certainly outranked the English coaches.

Flavigny

Two days later the trains were vacated at Les La umes and Pouillenay, Cote d’Or, and the regiment scattered in a number of small villages with regimental headquarters at Flavigny.

Flavigny proved to be one of the most picturesque spots the regiment struck while in France. The steep hill leading to the city, when negotiated under heavy packs, brought out all of the choice epithets of the American tongue and the all-around conviction that this hill was steeper and longer than any one of the Rockies could ever be.

But, when the entrance was reached, a big red, white, and blue banner with “France and America Forever” in English on it, stared everybody in the face and all along the line backs straightened out, rifles were brought up and legs snapped out a little more gingerly, for this seemed like those last days at home.

American and French flags were out, and the mayor and other distinguished gentlemen of the town, looking for all the world like our own senators back home, were out with a hearty handshake to greet the regiment.

The official welcome given the regiment, the first American troops to arrive in this part of France, was whole hearted and mighty impressive. But the welcome didn’t end there.

While the men were being shown their billets, and afterwards, these folk could not do enough. Their first cries of “Vive l’Américain, vive l'Américain” lingered and when billets were reached, luxuries such as eggs and milk, which had not been seen in some time, came out from somewhere. The barn billets in Cote d’Or seemed less damp and more cheerful than those of other places to come.

After having been squared away, and taking a hasty look at the surroundings, the men were invited in to “break wine," so to speak, with the inhabitants.

There wasn’t any "parleying” for outside of "pas compres” the bulk of the regiment were as newborns in conversation. The only really busy man in the company was the fellow who could get away with the talk.

The cordiality’ of the reception and the hospitality- of the hosts more than made up for the corned willie and hardtack that were the rations, and the days without smokes.

Chanipey and Hericourt

Four days later came orders to roll 'em up and hike. Les La umes was the entraining point. Not a few of the people of the villages about Flavigny went down to Les Laumes that afternoon, lor these Americans were surely going to the front.

News came early that day that the American army had made a drive—later the newspapers confirmed the fact that the St. Mihiel salient was being wiped out. The regiment hoped that St. Mihiel was the detraining point, and rumor insisted that it was. But after 60 hours, Hericourt was reached, and the regiment again scattered in villages, with headquarters at Champey.

The 1st Battalion went to Coisevaux and the 3rd Battalion was at Verlans and Byans. Gas masks and tin hats were handed around the second day, and a few days later, the first detachment of officers and men were sent up to relieve parts of the 29th Division who were holding the front line in Alsace.

The first day in this area gave everybody to understand that we were near the front, for a grumbling was audible at times, and lively scraps between the French antiaircraft and the German plane were daily occurrences. The first thrill came with the first air raid, when the Germans dropped bombs on Hericourt and vicinity one night, illuminating the landscape and inflicting casualties on some other units of the Division.

The "Flu"

Then officers of the regiment returned who had been on reconnaissance at St. Mihiel and in the sector in Alsace, yarns were told, rumors spread and everybody itched to get up and get some first-hand information.

At this stage, the advance party, which had preceded the regiment to France, and had been attending schools, joined and assisted in putting the finishing touches on the training.

In this Champey area a most thorough acquaintance was made with one of the most famous of the institutions of France—the manure pile.

Officers insisted they be removed, and inhabitants were just as insistent that they remain “put.” The policing of the edges of those heaps was never finished and just as fast as the streets were swept and shined up, somebody drove over them with a load, and the same thing had to be done over again.

The incessant rain and mud helped to make the days of those who were policing merrier, yet the work was done with cheerfulness—outside of the growling that is a religion with soldiers.

Up to this time Spanish Influenza was some new tangled word that meant nothing to the regiment. But in the Champey area it struck the regiment and strong, husky fellows who had never been on a sick report suffered as they never had.

The men were sick—training delayed -- for at times as many as 50 percent of the men in the companies were on sick report—with the “flu.’’ During the epidemic the regiment was saddened by the loss of a number of its members.

All that good comrades could do to alleviate the suffering was done ; men and officers drilled and trained in the rain all day and hustled dainties and comforts for the sick during the night.

The medical staff never slept and it was due to their vigilance and never-tiring energies that 95 percent of those sick are healthy men today.

In Action

Then the "flu" began to wane, and during the first days in October orders came that the regiment would take over a sector from the French, and to get up where the fighting was "toot sweet."

Packs were rolled, ammunition issued, dog tags inspected, and on the 4th of October everybody except the town majors and those still weak from the "flu" started on that 50 kilometer hike through the foothills ol the Vosges.

The first stop was at Tretrudans, near the Swiss border, reached at two o’clock in the morning. The daylight hours were spent in sleeping and nursing lame shoulders and sore feet, but at five that night, the columns re-assembled, did squads right, route step, and headed east.

It was raining when the march started and continued long enough to add twenty pounds to the weight of packs, and make the going underfoot slippery and treacherous.

Nothing was said—small men with packs as large as themselves hiked along and guyed some big "buck” who was growling because his “damned pack weighed a ton.” Men kept in ranks that night—pride of organization would not permit anyone to fall out and have the ambulance bring the packs.

In Company L one diminutive private, too dog tired to light a cigarette during the rests, suggested to "Davey," his bunkie: "Davey, I’m just too damned tired to put one in front of another any more, an’ this pack’s sure some hell."

"Most there now, Jimmy, and stick’er out ol’ timer, for we’ll get ‘boo coo’ sleep when we do get there. An’ here, lemme carry your gat a spell. I ditched one of my blankets 'n my bully beef and my pack ain’t as heavy as your’n. Wonder how much further this damn road runs."

Three hours later those same two, along with every other man who started in the column, were still in ranks and plugging along. Then a ripple went down the line for somebody said Germany and the Lieutenant confirmed it—we were in Germany.

The next village settled it. The houses were different—the towns looked different, and the streets were wider. The grumbling of the guns to the east had changed to a rumble and a dull “boom,” and the sky flashed red.

The lines were off there—just a bit, and a moment later, the star shells could be seen. Then a part of the regiment broke off from the column, during a rest, and the Machine Gun Company pulled by.

The sight of those machine gunners, laboring under their packs and dragging their heavy carts and guns behind them, made the doughboy sit up and the grumbling about rifles and packs ceased; for these men, besides doing a soldier’s work on a hike, were also doing the work of the mules that the regiment didn’t have, and their cheerfulness and sassy repartee brought back the pep.

The last stage of the journey for that night was at hand and a short while later, Dannemarie, Manspach and Gommersdorf were bustling places— for soldiers were looking for their billets.

By five o’clock that morning everybody was hitting the hay, some with clothes still on, but getting the “boo coo’’sleep “Davey” was telling about.

Next noon every top sergeant in the regiment was telling the captain: ‘‘This company has certainly got the guts, Cap’n, nary a man fell out.’’

The regiment was at the front, just a few kilometers back. The artillery firing was no longer the rumble and grumble—it spoke in sharp tones and cracked viciously.

The first baptism of fire for the entire regiment came that morning at about eight o’clock. The Germans were raiding the front line, and the artillery was deafening. At that time everybody sort of set himself, getting ready for anything that might happen to come over, but after an hour or so, the intensity of the fire died down and went back to normal.

During the raid enemy reconnaissance by airplane was particularly active, and a beautiful scrap between eight French and German planes took place. The Germans did not get back over the billets where the regiment was located. One plane succeeded in sneaking away from the party, but was promptly headed back by antiaircraft fire.

That morning regimental headquarters, which had been established at Manspach, called in the officers of Companies B, C. I and K and told them to make ready to take over the sector that night. Orders were to get up to Hagenbach and Badricourt, headquarters of the 3rd and 1st Battalions, and make a daylight reconnaissance of the sector. That being done, be ready to take the platoons in that night.

At four o’clock that afternoon the companies selected to do the first hitch started out in columns of twos. Then they split into columns of files, one file on each side of the road, keeping well alongside the camouflage to escape observation by the enemy planes.

The 1st Battalion companies went into the Carspach woods and the 3rd Battalion into the Schonholz woods. Major Evans commanded the 1st Battalion and Captain Burnham the 3rd.

While the regiment was back at Champey the Intelligence platoons had been formed under Captain H. G. Carpenter. The 1st Battalion was under Lt. Rowland, the 2nd under Lt. Eckerman and the 3rd under Lt. Murphy.

A stiff two weeks’ training course was spent at Vyans and at the time the regiment was ready to take over its sector, the Intelligence section, with its scouts, observers and snipers, was ready to do its work. They had preceded the regiment into the sector by three days and were ready to tell what to do and how to do it.

The advance party was in the lines, and had been for two weeks, and their assistance for the first few days was invaluable to the other men. They had been on patrols, had been in raids, and were ready with the assistance that was needed.

On the night of October 7th, after the platoons had reached their respective battalion headquarters, they were taken charge of by their officers and the march through the woods and up the communicating trenches begun.

The support lines were passed and by nine o’clock the platoon P. C’s. reached. At this point the men of the regiment stood their second baptism of fire, for while the men were outside, waiting for guides to take them to their respective posts in the front lines, a short bombardment of the lines was made by the Germans.

No casualties were inflicted. The rifle fire, the Very lights and the incessant pop-popping of the machine guns brought war closer now than it had ever been.

The relief was made without trouble, and by eleven o’clock word had been sent back that everything was O. K. in the lines and that the regiment was ready for any party that might be called for. During that night nobody slept.

The French, with whom the regiment was brigaded, were on the alert, looking for something to pop, for as the regiment later came to know, it certainly would not have taken an expert to know that there were greenhorns in the outposts.

Considerable ammunition was expended that night with no visible results. About two o’clock the next morning a red rocket shot up from the sector down the line, and the warning went up the lines, and gas masks donned. After thirty minutes and no gas, everybody rested easily again. Morning broke and a hasty inspection of the trenches made.

The sector was the southern subsector of the center sector Haute-Alsace—a sector that had been the scene of much vicious fighting. The once heavy forest was a mass of debris. Few trees were standing and the trenches had been pummeled by constant artillery fire until shallow ditches were all that remained.

Acres of barbed wire and shell holes stretched out to the front—and over across the way—about 1000 yards was a line—the German front line. So this was “No-Man’s” land.

The French who were with the regiment were the 4th Zouaves, one of the most famous of all the French. Wearing seven citations, it was the proud record ot the Zouaves that they had never been defeated.

In before Verdun four times, and in .ill of the great battles of the war, these troops were the cream of the French so-called “shock troops.” Their daring and boldness were admired, and a few days later the regiment learned from them how successful patrols and raids were carried out.

The first-line companies were in for four days and then relieved. Companies “A" and “D” took oxer the sectors of “B” and “C,” and Companies “L” and “M” relieved “I" and "K," while those who had been up trout moved back into support.

The first night after the relief had been made, the Germans opened upon Eglingen, a small town within the American lines, and an intense bombardment of two hours’ duration was laid down, Company “M” receiving the brunt of the trouble.

Over 1600 high explosive shells dropped in the sector and at this time the regiment sent back the first names “Killed in Action." A gas attack was launched at the same time, affecting the entire front.

They were putting on a big party up to the left, across the canal, for the air was charged with something that night that told there was a battle on. The front lines were destroyed, the men placed themselves at the points of resistance and with gas masks on, opened up a fire over to the left.

The lieutenant got word from somewhere that fire in that direction would help. The machine gun outfit was sending it in as last as the guns would fire, and the Germans were coming back with machine gun, rifle and grenade, as well as intense artillery fire. The vicious whip and roar of the H. K.shell made its impression that night, and cultivated a wholesome respect.

But two men in the regiment were caught when the gas came over. The red sheet of flame announced the coming of the projectors, and masks were put on and kept on.

After the fight satisfaction was felt that the regiment had stood its first attack. The men were veterans, each knew what to do and did it. No longer recruits, but fighting soldiers with a definite purpose in mind.

This fact was brought out by men of the Headquarters Company, who stuck with the game, who worked their instruments until the shell fire destroyed the wire, and then got out and repaired the breaks; by men of the medical detachment who got on the job and did their part in the front lines; by all men of the regiment who got down to business and said to themselves: “Let her come.” Eglingen, a name that will bring back memories as long as men of the regiment and division live.

Two nights later another raid was made on the lines, this time Company “A" taking the medicine. After a short but intense artillery preparation, about forty Germans came over, but were promptly driven out. The attack was made in the Stockette Woods, but results were nil.

The following night the 1st Battalion again had their little party, this time Company “C”, who had come into the lines for a second session, having the show. A German raid was made on one of the outposts, but the Americans had "partecd."

The post raided was occupied during the day time only, so after a line artillery preparation, over came Jerry. He was given a cordial reception by the other posts, hut found the post being raided, empty.

Companies “B,” "C,” ‘‘I.” "K," “L” and “M” were again in line. On the 18th of October at 11:10 a. m., during a fog, the Germans came over in force on the Schonholz sector.

Shortly before the raiding party reached the lines, the fog raised and they were discovered. Fire was opened immediately, the Machine Gun Company getting in particularly effective work. Upon being discovered, a barrage of 77’s, 105's, and 155’s, along with machine gun fire was laid. A hand-to-hand fight with grenades and rifles took place, the Germans retiring after a short time.

The 2nd Battalion, under Major Robinson, had been held in reserve at Romagny up until October 15th, when they were ordered into the lines in the Pulieren sector. Companies “F” and “G" were in for the first hitch.

Companies of the 2nd Battalion took their first shell fire when coming up, for at that time, the roads behind were given a hard shelling. Immediately upon their arrival in the line, they became active with patrols, and under the able tutorage of the French Zouaves, soon became proficient in the “hit and get away quick” stuff.

On October 17th, the French turned over the sector to the regiment, and from that time on until October 25th, the regiment was “on its own.” The regiment became particularly active with patrols and raids, being out every night on reconnaissance and fighting missions.

It was while on patrol duty that Lt. Mathew D. Eckerman, Intelligence officer of the 2nd Battalion, was killed. On October 25th the 352nd came up and took over the sector, the 351st moving back into reserve.

During its stay in the lines, the regiment found the lack of transportation rather serious. The entire division of 2S,000 men had one motor truck with which to keep up provisions, so delicacies were left out. Corned beef and hard bread, washed down with a good hot shot of coffee, is good grub when men are hungry.

When the regiment left the trenches, Companies "I" and "A" remained with the 352nd, and after a grueling hike in the ever incessant rain, went into billets in the Montreaux Chateau area. Camp Norman and Lutran were occupied by the battalions. It was here that training was resumed and preparations made for the big push to come later.

On the night of October 31st, the longest and hardest march up to this time was taken. The regiment moved into the Belfort area. Regimental headquarters was at Errevette, the 3rd Battalion and Machine Gun Company at Hvette, the 1st Battalion at Sermamgany and the 2nd Battalion at Chaux.

The 2nd Battalion during its stay in the lines lost Major Robinson, who was sent to America to instruct, and Captain Blanding, Company “C,” who had been promoted to Major, took his place. The 3rd Battalion, while still at Hericourt, lost Major Fulton, who was promoted and returned to the States, and the Battalion and regiment lost another of its best soldiers and friends.

It was at Errevette that Companies “A” and "I” rejoined the regiment, after twenty