Edward Molyneux: Designing for Ocean Travel, Elegance, and Empowerment in the 1920s

📌 Explore the refined elegance of Edward Molyneux's fashion designs from 1920–1929—tailored for world travelers, actresses, and royalty. Discover the intersection of couture, culture, and ocean liner life through the GG Archives.

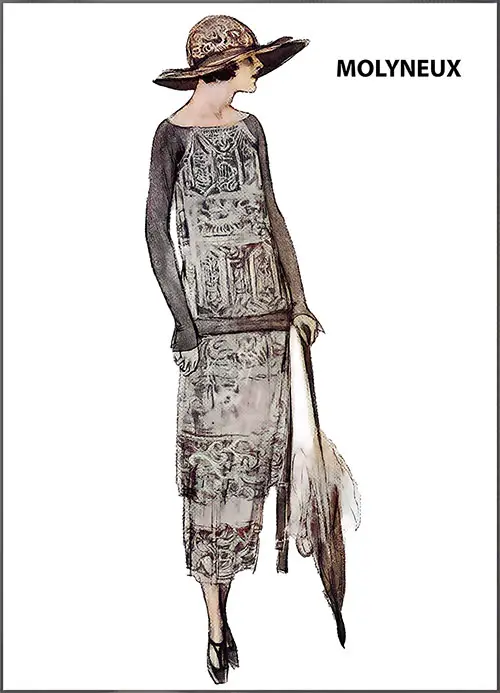

The Illustration Above Is a Characteristic Afternoon Frock by Molyneux, Made of Beige Lace and a Deeper-Hued Crêpe. Notice the Tunic Effect and the Long, Closed Sleeves. Illustration by John Lagatta. (Woman's Home Companion, July 1924) | GGA Image ID # 1cd3380e88

👑 Elegance in Motion: The Fashion Legacy of Edward Molyneux and His Global Influence (1920–1929)

From the salons of Rue Royale to the grand transatlantic liners, Edward Molyneux dressed the world’s elite in some of the most graceful and modern garments of the 1920s. This stunning archival profile from the GG Archives provides a rare window into the evolution of modern fashion, the rise of the cosmopolitan woman, and the seamless blending of travel and couture.

🌍 Molyneux's work reflects the changing world of post-WWI society: women were becoming more mobile, more independent, and increasingly visible in the public sphere—especially on ocean liners, in European capitals, and on glamorous world tours.

The tunic, with its implication of width, in contrast to its narrower underskirt, favors those who would like to be slender and does not harm those who are. Naturally, it is popular, and often, when it does not appear, it strongly influences the mode.

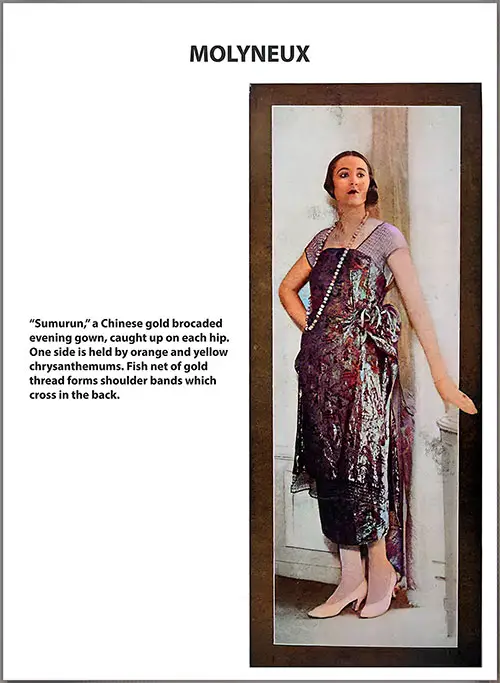

“Sumurun” Is a Chinese Gold Brocade Evening Gown by Molyneux Featuring Distinct Details on Each Hip. One Side Is Adorned With Orange and Yellow Chrysanthemums, While a Gold-Thread Fishnet Forms Shoulder Bands That Cross in the Back. (Garment Manufacturers' Index, September 1920) | GGA Image ID # 1a4e16602a

Duvetyns and Corduroy in bright blues and browns, with little fur trimming, are used for suits and dresses for this house.

Although barely a year old, the House of Molyneux is the most promising junior firm. Its success was lastingly confirmed by a daring winter collection.

Captain Molyneux, who served in the British army late and was once connected with Lucile, was the directors' most active. He designed and created his salons, where every model is shown.

Recently transferred to 5 Rue Royale, Captain Molyneux found time to decorate the magnificent suite of grey rooms, the ideal backdrop for the rapidly becoming famous dresses.

A Golden Gown for a Modern Sultana: Made For the Wife of Fuad I, Sultan of Egypt. This Exquisite Embroidered Evening Gown, Designed Specifically for Her Highness the Sultana of Egypt by Captain Molyneux, Features Shimmering Fabric and Intricate Embroidery With In-Fold Tubes and Cut Beads. The Gown Also Has Shoulder Straps Embellished With Gold-Colored Stones. The Sultana of Egypt, Married to Fuad I, Is the Daughter of Sabri Pasha. They Were Married in 1919. Photograph by Drabantin; Dress by Molyneux, Rue Royale, Paris. (The Sketch, 15 December 1920) | GGA Image ID # 224bbe2509

Molyneux Creates a Flared Silhouette by Graduating the Flounces of This Gray Crêpe de Chine Dress. It Features a Gray Embroidered Net Trim and a Lilac Ribbon Band Marking the Waist. The Delineator, August 1921, p. 58. | GGA Image ID # 1cd4914365

The grey taffeta curtains part, and model after model glides in, each one simply tailor-made to gorgeous evening gowns. This striking originality and new idea bring us elegance. The dress's elegance is expressed in beautiful, unbroken lines and a distinctively simple cut.

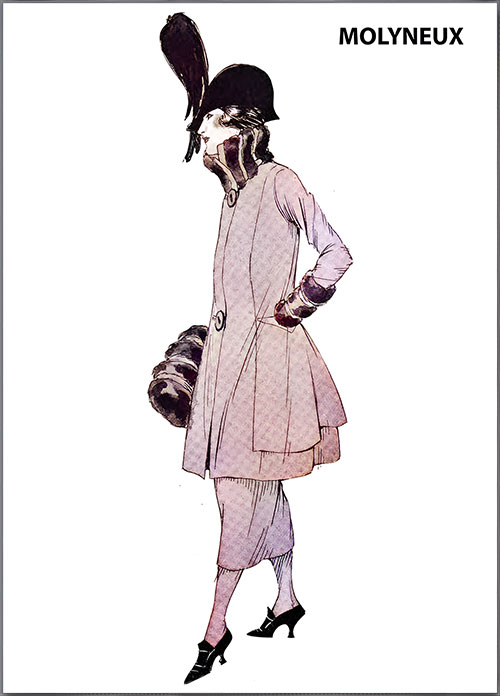

Duvetyns and corduroys are much employed in bright blues and browns for tailor-made, mostly three-piece dresses. The long lines here make it easy and smart to wear a shortish, loose coat, forming a straight outline with the tight frock underneath.

The little jacket, reaching just below the hips, is either loose and fastened at one side, as in the case of a practical brown leather coat combined with a skirt of the same-toned gabardine, or, like a dark blue corduroy, slightly trimmed with grey astrakhan around the high collar and cuffs, the coat gathered and flaring out from the hips.

Once Again, This Maison Molyneux Ensemble Features a Fitted Skirt and Long, Full Jacket Made of Blue-Green Cloth. The Collar and Cuffs Are Made of Hudson Seal Fur. The Unusual Hat Is Reminiscent of Those Worn by French “Polytechnicians." Photo by Talma. (La France, November 1920) | GGA Image ID # 1cd15211a7

The collars are interesting. The huge, enveloping, turned-over kind is brilliant, while the high, loose, straight one forming a right angle with the front of the coat expresses quite a new idea.

The sleeves are long and flaring, widest at the cuff; the dresses underneath the coats are simple little affairs buttoned down the front, with a loose belt emphasizing the low waistline.

Fur is rarely used except for a touch here and there on a coat or walking suit. We make up for it with a priceless collection of fur evening wraps, which we will discuss later.

The whole scale of browns is favored for day and silver for evening wear. The one characteristic of all styles of dresses is the lowered waistline; many bodices join the skirt well below the hips.

Bottle Green Velvet Is Here Trimmed With a Magnificent Gray Fox. The Length and Fulness of the Jacket, the Odd Little Sleeves, and the Girdle of Gray and Green Beads Are Distinguishing Features of This Tailleur. (Maison Molyneux). Photo by Talma. La France, November 1920, p. 85. | GGA Image ID # 1cd159649c

A beautiful model worn by the no less attractive Hebe is of golden brown chiffon velvet. The long, flat line of the bodice is accentuated by a shirred knee-length tunic edged by a broad band of red fox.

Duvetyn, gabardine, and chiffon velvet are popular for day dresses. Here again, we have tight, plain lines, the robe-chemise, straight and even beltless, redeemed from absolute simplicity by an exciting cut.

The cape effect, for instance—a square detached panel falling from the shoulders to the hem or, as in the case of a beautiful black velvet example of the severely plain, with its high turned-over collar, tight sleeves, and flat blouse, where the skirt forms a diversion by having a sort of detached "apron" from hip to hip at the back, rather long and trimmed by a large band of monkey, which seems not to have said its last word.

A gorgeous afternoon gown of pale biscuit crêpe gives us another line. The crossed bodice has a little turned-over collar of delicate gray lace; the skirt is also crossed and draped a trifle to one side in front, while the square train is a panel starting from the waist.

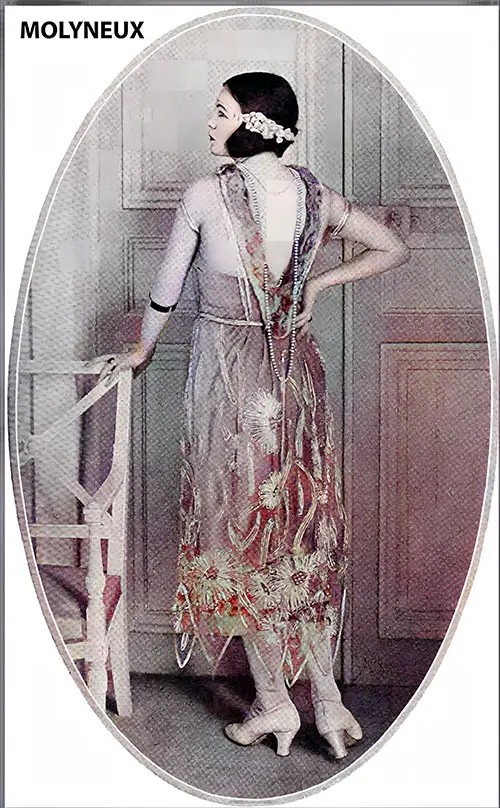

Evening dresses may be divided into suitable dinner gowns and frocks for more elaborate functions. Both favor long, clinging lines and graceful draperies.

The materials are fantastic: gold and silver lamés, threads, and a good deal of metal laces. Velvets are effectively used, plain and unadorned; net cut into points and superposed often makes ethereal filmy skirts.

This Exquisite Gown From Maison Molyneux of Pearl-Gray Satin Embroidered With Tulle in Silver Gray Is Unusual for Shoulder Straps and the Petal-Like Cut of the Overskirt. The Novel Headdress Is Worth Noting. Photo by Talma, Paris. (La France, November 1920) | GGA Image ID # 1cd2b12f79

The same idea is also interpreted in different tones of silk muslins: petunia and flame, magenta and blue, two daring combinations I have in mind.

I must describe this elegant evening gown as characteristic of the entire collection of geranium velvet. The bodice drapes into a point over one shoulder, the other shoulder bare but for a jeweled strap (this is a new idea and gives an unexpected line).

A long square train starts from the waist as a detached panel trail at least a foot on the ground; the skirt follows the famous enveloping movement.

A seemingly seamless band of the material starts from one hip, winds around the wearer, and drapes slightly up on the other side. This gives a tight hemline and causes the skirt to cross and open at the feet.

Low décolletés persist, and the shallow back is still seen. Sometimes, as a concession, a loose lace fichu with very long filmy sleeves appears over bare shoulders. In contrast, a tunic is worn over the skirt.

Sometimes, a lace cape starts from the back and falls to the waist, as in the case of a gray brocade dinner gown; again, we have tulle or lacewings. One good example of this is a dress of clinging net covered with huge gold and silver flowers draped up to the shoulder in one unbroken line, with black lace wings forming two tiny trains.

A Royal Robe Designed by Molyneux and Modeled by Hebe Is Made of Coral-Colored Panne Velvet, Beautifully Stamped With Large Silver Flowers, and Trimmed With Pearls. The Conventions of Evening Dress Have Changed Significantly in Recent Years, Leading to a More Relaxed Approach, Even for Formal Dinner Gowns. While the Classic Draped Gown Is Still Crafted From Materials Such as Metal Brocades, Velvet, Brocés, Satins, and Heavier Crêpes, These Dresses Are Now Typically Shorter and Sleeveless. They Are Often Worn Without Traditional Formal Elements, Such as Trains and Long White Gloves. Photograph by O'Doyé. (The Delineator, January 1922) | GGA Image ID # 1cd50c532c

Another unusual way of treating a low neck is as follows: an evening gown of black gauze with a gold spot design, short and tight in front, low on the shoulders, becomes an immense long cape curving around the arms and fastening at each hip, the interval belted by a band of flat roses; this cape is very long in the back, descending from invisible tulle shoulder straps.

Dinner dresses, which are, as a rule, very short, frequently have a filmy over a skirt of silver lace or tulle, which is much worked in different metals, the tunic mainly being longer than the underskirt.

These loose but not voluminous tunics indicate the crossed bodice and tiny sleeves; metal lamés make practical foundations for tunics. I noted a very happy instance in a silver slip with a black net tunic faintly traced over in fine black straw.

Another attractive movement is the robe-chemise effect, applied to evening gowns; Molyneux uses some beautiful transparent stuff, a net embroidered with sequins in one instance, and winds it once and a half around the lining.

It falls in long, seamless draperies and is held to the figure in the back, the front, or both by a beaded cord; as a rule, we have the rounded neck and short sleeves here.

Molyneux Braid-Trimmed Mustard Crepe Street Dress. (The Ladies' Home Journal, April 1923) | GGA Image ID # 1cd54e8d8a

One straight chemise of silver lace over silver lamé is simply two widths: the front width is short, and the back is long enough to form a square train.

Who can describe the gorgeousness of ermine, kolinsky, seal, and broadtail evening wraps? They are vague, enveloping capes with huge kimono sleeves lined with beautiful brocades.

One magnificent ermine example with a huge shawl collar is spotlessly white, but for a row of tiny tails at the hem; a squirrel wrap is particularly chic with its white lining striped in black velvet; a white panne velvet cape has a second shorter cape over the shoulders and an immense ermine collar.

I noticed good traveling coats built along the same loose lines with huge comfortable collars and sleeves: one orange blanket cloth fastening down the side, with a chic collar rolled, very high, and standing out from the face.

Molyneux Designs a White Gown. The vogue for white is shown in this frock of twilled silk, designed exclusively for the Woman’s Home Companion by Molyneux, the young English war hero, whose new establishment on the Rue Royale is drawing the fashionable to its doors. Painted by Ruth Eastman. Designed Exclusively for "The Woman's Home Companion." (The Woman's Home Companion, April 1921) | GGA Image ID # 224b95bbc7

Molyneux: The Curtain Rises on the Paris Mode (April 1921)

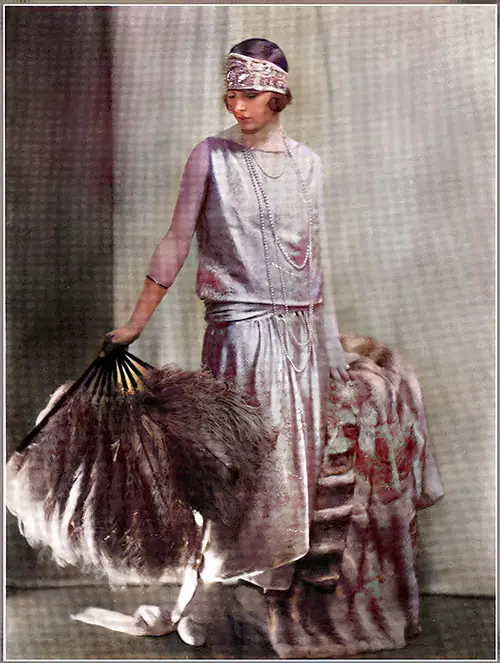

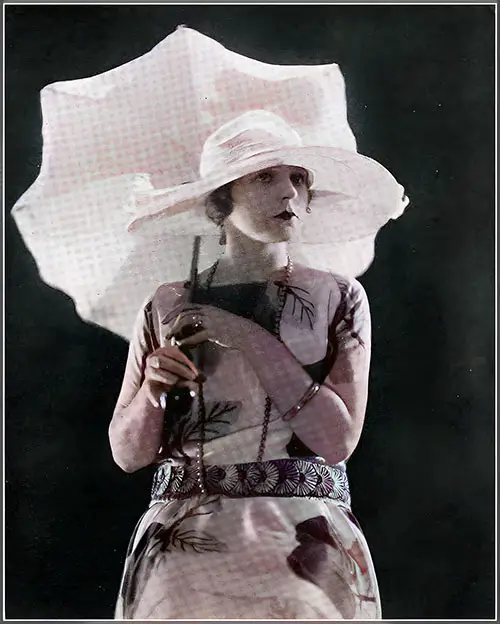

Molyneux advocates long, slender lines and draped gowns for the evening. There is a refreshing lace revival, with a special fondness for the Venetian. For lace frocks, one sees cream or embroidery over black satin, and a striking evening model shows a short, straight overblouse of silver lace over draped yellow brocade.

Smocking Molyneux on the hips appears again, and plain black dresses persist for the afternoon and evening. Many three-piece suits have long, straight coats and various crepe dresses.

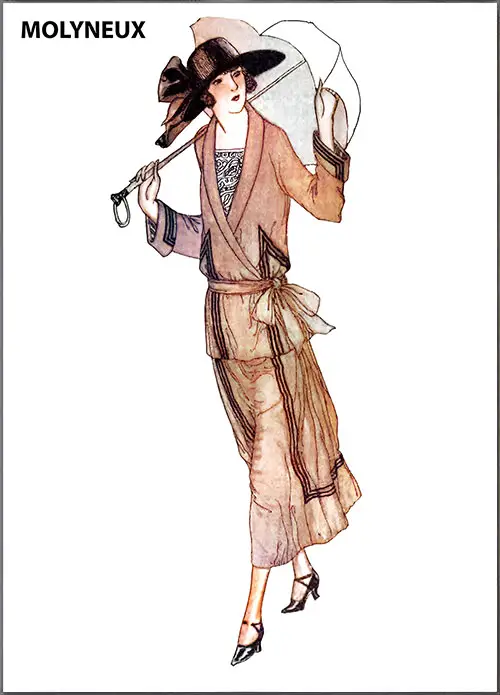

Tailleurs wear short pistol coats, sometimes belted but more often straight. Traveling clothes are simple and almost boyish, with plaid coats and skirts and dark belted blouses. For colors, Molyneux shows jade green, yellow, and a good deal of black and white combined.

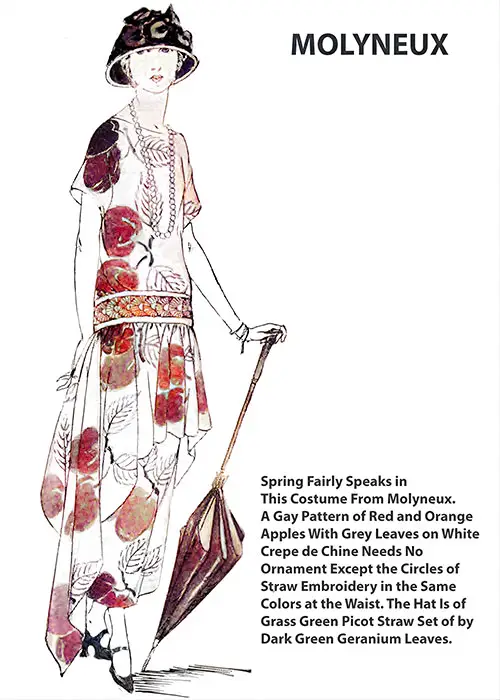

Spring Fairly Showcases a Costume From Molyneux Featuring a Vibrant Pattern of Red and Orange Apples Set Against Gray Leaves on White Crepe de Chine. The Outfit Requires No Additional Embellishments Except for the Circles of Straw Embroidery in Matching Colors at the Waist. The Hat Is Crafted From Grass-Green Picot Straw and Adorned With Dark Green Geranium Leaves. (Vogue, 1 April 1922) | GGA Image ID # 224bb0ec0d

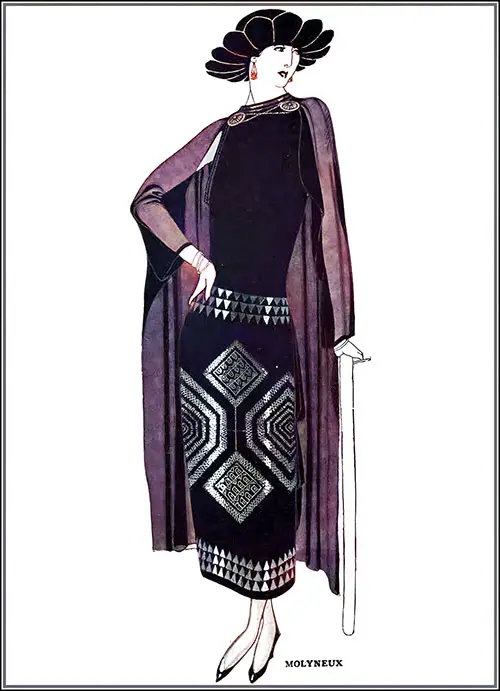

This Molyneux Gown Strikes a Unique Balance; It Is Somewhat Too Austere for the Orient Yet Too Exotic for the New World. However, It Perfectly Embodies the Subtle Charm of Paris and Molyneux. The Design Features a Blend of Dull and Bright Silver and Black Brocade, Complemented by a Sleeveless Blouse Jacket Made of Shining Silver. This Blouse Jacket Is Cinched at the Waist With a Belt Adorned With Steel Studs. (Vogue, 1 April 1922) | GGA Image ID # 224bcc8874

This Striking Cape Costume From Molyneux Is Made of Black Silk Jersey. The Dress Features Machine-Embroidered Tarnished Silver Accents, and the Cape Is Secured With Silver Plaques. The Hat Is Crafted From Shiny Black Straw. (Vogue, 15 April 1922) | GGA Image ID # 224c087b87

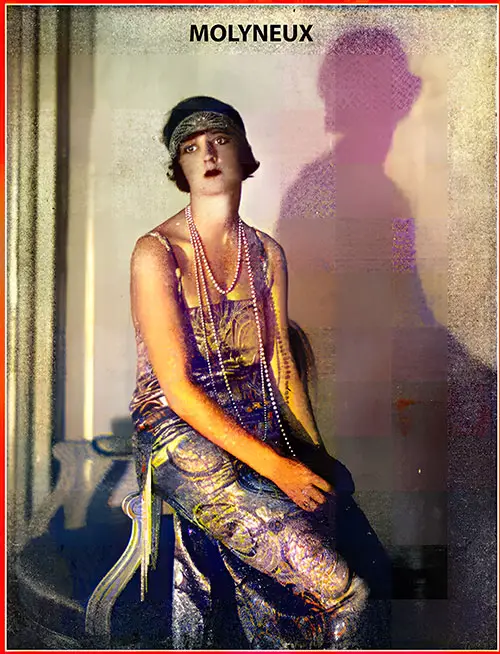

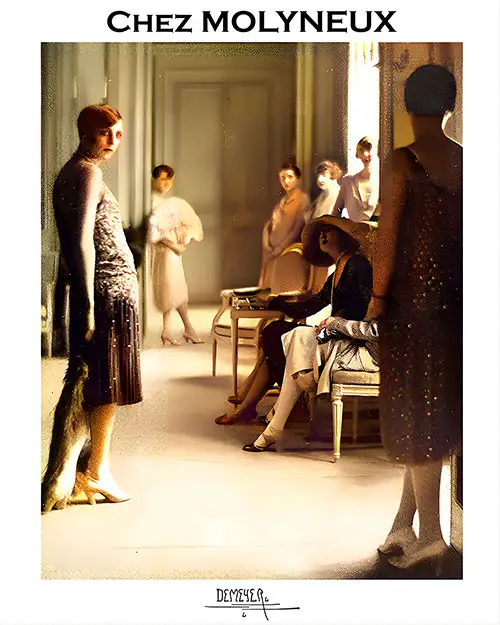

Chez Molyneux. Photo par Baron De Meyer. Tous Les Modeles Deposes. (Harper's Bazar, October 1927) | GGA Image ID # 226f915faf

Chez Molyneux (October 1927)

Molyneux's collection is a testament to his rare ability to produce gowns that enhance a woman's appearance of youth and slimness and exude unparalleled elegance. The secret of this achievement resides in his skillful 'abbreviation' in both width and length, in the discarding of all superfluous material. This technique sets his gowns apart in the world of haute couture.

The Molyneux silhouette, recognizable anywhere, is a testament to this talented Anglo-Parisian designer's unique point of view on clothes. His excellent line entirely dominates his models, and he repeats the almost identical shape in endless variations throughout his collection. Despite the seemingly similar shapes, Molyneux imparts a sense of variety by changing textures, color, and detail work, showcasing his boundless creativity.

Molyneux's sartorial cleverness is genuinely astonishing. His sports clothes are not just excellent but also remarkably free of any superfluous elements. His novel details, such as the improved cut on last year's models in tricot sweaters, creased comfort in sports skirts, and more serviceable overcoats, are a testament to his design skills. Molyneux's true talent lies in his ability to conceive clothes as ensembles. This skill sets him apart in the fashion world.

A slim little gown and an even narrower wrap are combined to become either tiny or wide-brimmed headgear. His new notes are uneven hemlines and little sleeveless boleros worn over evening gowns. He is very faithful to beaded gowns. These are fashioned in glittering textures with merely a flower or jeweled ornament at the waist as a finishing touch.

Short crystal fringes are made into skirts with plain georgette or velvet bodices. Numerous diamonds are on dark velvets, brilliants on white materials, and richly embroidered evening coats.

Molyneux, the master designer of elaborate and dressy pajamas, shows many delightful garments. One is made of rose velvet and combined with a mauve chiffon coat edged by a border of voluminous mauve feathers.

Another is pale gray satin embroidered with pearls to be worn under a pink mauve and gold brocaded wrap. A pair of scarlet velvet pajamas combined with a black chiffon coat edged with scarlet velvet roses en relief. It is most effective.

The Molyneux Collection Showcases a Series of Elegant Evening Gowns Crafted From Supple Silk and Metallic Brocades. These Gowns Are Designed With Simplicity, Featuring Semicircular Tucks That Elegantly Drape Over One Hip to Enhance the Silhouette. This Particular Molyneux Gown Comes In a Beautiful Hyacinth Blue and Gold Brocade. the Tucks That Create Fullness Seamlessly Connect to a Girdle, With the Ends Extending Into a Double Train at the Back. the Gown Reflects the House’s Preference for Moderate Lengths and Décolletage, Except for Its Most Formal Pieces. (Vogue, 15 April 1922) | GGA Image ID # 224c44b5bc

This Charming Costume Evokes Memories of a Wide Lawn and Sunny Brack. The Design Features Cheerful Apples on a Crêpe de Chine Frock Created by Molyneux, Which Mrs. Dean Bushby Wears. The Girdle Is Adorned With Straw Daisies. Completing the Look Is a Wide Réboux Hat Made of White Organdy Embellished With Two Lilies on the Brim. (Vogue, 15 April 1922) | GGA Image ID # 224c913f9b

The Mode at Molyneux’s, October 1928

The Molyneux collection is comprehensive and distinguished. The evening silhouette is slim and sheath-like to mid-thigh, below which the material is released to flare and flutter in disciplined fulness of uneven width and length.

There is a noticeable side movement, and a few chiffon dresses have trains reaching almost the floor. Flat tiers and flat ruffles are applied diagonally, vertically, and oval and often end in bows. A new and insistent note uses elongated fan-shaped panels in vertical tiers at one side of both coats and dresses.

The waistline is low and slightly bloused to give a becoming fulness above tightly and horizontally swathed hips. On some dresses, the blouse disappears entirely, and there remains a modified princesse line with a soft chiffon belt or molded incrustations to indicate the waist.

The important dress for important occasions is developed in stiff, heavy fabrics: Molyneux's new 'Renaissance' velvet, similar to the hatters' velvet of bygone days, stiff lustrous satin, brocades, and the new metal matelassé. These are fabrics that exude luxury and are reserved for special events.

Fulness in these materials finds expression in circular flounces, fan-shaped tabs, and panels. A gold matelassé dress with a square, nude décolletage, a sheath-like body continued to a point well below the hips, a slight blouse, and stiff flaring side flounces is the most important expression of this attitude.

The practical evening dress for restaurant wear, dancing, and theatre follows the same silhouette. Still, it is developed in less important and rigid materials: supple lamé, artificial velvet, chiffon, marquisette, lace, tulle, and georgette crépe.

Chiffon dresses have flat, overlapping panels released from diagonal incrustations and hip bands; velvets are much swathed and molded; and lace dresses sometimes attain a partial fir-tree silhouette by using side ruffles in tiers.

Reds of all shades, including Bordeaux, claret, flame, and tomato, deep browns, beige from grey to gold, black, white, gold, indigo-blue, rose, peach, and soft crocus-yellow—these are the dominating evening colors. Lustrous satins and velvets bring out the latent depth of the reds and browns, and the delicate shades are lovely in laces, chiffons, and tulle.

Molyneux's use of the naturalistic artificial flower is important. He uses it on evening dresses and redeems it from the dowdiness, or lack of stylishness, into which it had fallen. Cabbage-like carnations, three in a row, are often set below the left shoulder, on the right back shoulder, and on the left hip.

The décolletage is usually square, with tiny straps, boleros swing slightly below the back décolletage, and belts are still conspicuous. A series of artificial velvet and lamé evening capes without fur is memorable. These have yokes and yoke-like collars; many have flounces that accent tightly swathed hips.

The daytime silhouette is straight and horizontal in feeling, with skirt fulness obtained by vertical pleats and panels. Molyneux insists upon the ensemble idea for the day, even more than most couturiers, and it is also behind the evening mode.

The ensemble idea' refers to Molyneux's belief that every afternoon dress should have its accompanying coat, creating a complete and harmonious look. There are three-quarters or full length, and there is much back interest.

Capes are set below deep yokes, and a fluttering skirt movement is often obtained by circular tiers applied below the hipline. Printed velvet dresses have assembled coats that are faced with a vent or a short or a long coat of the same material.

The down-in-back skirt movement is shown successfully for an afternoon in a mossy caramel-colored velvet with a three-quarters coat that wraps around to follow the down-in-back line of the dress.

Molyneux makes the short fur jacket very stylish and shows it in Breit-Schwartz, ermine, mink, and ensembles. He also combines georgette crépe dresses with wool coats.

More emphasis is on clothes' travel and town-and-country aspects than purely sports mode. Coats are beautifully cut and very simple. For sports, they are usually belted. They are short, three-quarters, and full-length; a few are leather-lined to the hips.

Tweeds and wool velours are the outstanding materials for these coats. They have voluminous collars of golden and dark brown beaver and opossum when trimmed with fur.

These coats are worn over straight, belted tunic dresses of oil silk or thick wool. Andrela is an excellent fabric for the runabout dress, and the incrustation of fat bows is a favorite motif.

Corduroy, printed velveteen, and jersey are used for both town and country and sportswear. The ensemble remains classic for sports, and Molyneux's idea of a cardigan to match a sweater in chevron and zigzag jersey is an interesting departure.

This house chooses all shades of brown and red, beige and green, and a combination of grey and green and black and navy blue for daytime.

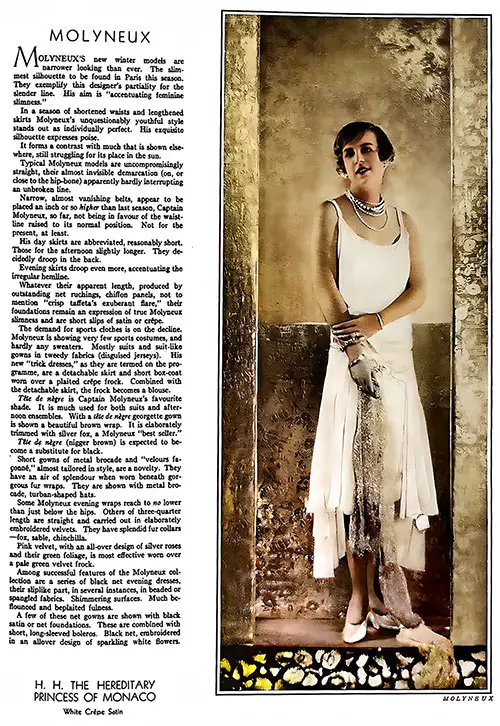

“H. H." the Hereditary Princess of Monaco Shown Here Wearing a White Crèpe Satin Gown by Molyneux. Princess Charlotte, Duchess of Valentinois (Charlotte Louise Juliette Grimaldi; 1898–1977), Served as the Hereditary Princess of Monaco From 1922 to 1944. She Was the Daughter of Louis II, Prince of Monaco, and the Mother of Prince Rainier III. She Was the Heiress and a Presumed Hereditary Princess to the Throne. (Vogue, October 1929) | GGA Image ID # 224cd24d66

Molyneux (October 1929)

Molyneux's new winter models are "narrower looking than ever. They have the slimmest silhouette to be found in Paris this season." They exemplify this designer's partiality (or the slender line). His aim is "accentuating feminine slimness."

Molyneux's unquestionably youthful style stands out as individually perfect in a season of shortened waists and lengthened skirts. His exquisite silhouette expresses poise.

It contrasts with much shown elsewhere, still struggling for its place in the sun.

Typical Molyneux models are uncompromisingly straight, and their almost invisible demarcation (on or close to the hip bone) apparently hardly interrupts an unbroken line.

Narrow, almost vanishing belts appear to be placed an inch higher than last season. So far, Captain Molyneux does not favor raising the waistline to its normal position—not for the present, at least.

His day skirts are abbreviated and reasonably short. Those for the afternoon are slightly longer. They decidedly droop in the back. Evening skirts droop even more, accentuating the irregular hemline. Whatever their apparent length, produced by outstanding net ruchings, chiffon panels, not to mention "crisp taffeta's exuberant flare," their foundations remain an expression of true Molyneux slimness and are short slips of satin or crêpe.

The demand for sports clothes is on the decline. Molyneux is showing very few sports costumes and hardly any sweaters. Mostly suits and suit-like gowns in tweedy fabrics (disguised jerseys). His new "trick dresses," as they are termed on the program, are a detachable skirt and short box coat worn over a plaited crêpe frock. Combined with the detachable skirt, the (rock becomes a blouse.

The de nègre is Captain Molyneux’s favorite shade. It is often used for both suits and afternoon ensembles. A lilies de nègre georgette gown is shown with a beautiful brown wrap. It is elaborately trimmed with silver fox, a Molyneux "best seller."

Tète de nègre is expected to become a substitute for black. Short, almost tailored gowns of metal brocade and "velours façonné " are a novelty. They have an air of splendor when worn beneath gorgeous fur wraps. They are shown with metal brocade turban-shaped hats.

Some Molyneux evening wraps reach no lower than just below the hips. Others of three-quarter length are straight and carried out in elaborately embroidered velvets. They have splendid fur collars —(ox, sable, chinchilla. Pink velvet, with an allover design of silver roses and their green foliage, is most effective worn over a pale green velvet frock.

Among the successful features of the Molyneux collection is a series of black net evening dresses, which are slip-like in several instances and made of beaded or spangled fabrics. They have shimmering surfaces and are much be-flounced and be-plaited.

A few of these net gowns are shown with black satin or net foundations. These are combined with short, long-sleeved boleros. The net is black, embroidered with an allover design of sparkling white flowers.

Bibliography

"Molyneux" in the Garment Manufacturers' Index, New York: The Allen-Nugent Co. Publishers, Vol. II, No. 2, September 1920: 20.

Baron de Meyer and Marjorie Howard, "What Is New in Paris: The Autumn Collections of The Great Paris Houses: Chez Molyneux," in Harper's Bazar, New York: International Magazine Company, Inc., Year 61, No. 2580, October 1927: The Paris Openings Number, Illustrated By Baron de Meyer, Bernard B. Demonvel, Mary Mackinnon, Reynaldo Luza, and Dynevor Rhys, p. 79.

The Paris Openings: The Mode at Molyneux's." in Vogue, New York: The Condé Nast Publications, Inc., Vol. 72, No. 8, 13 October 1928. p. 172

🛳️ Ocean Travel Relevance: Clothing the Cosmopolitan Voyager

While the article is devoted to Molyneux's designs, his influence was especially prominent in the context of luxury travel, including:

Traveling Ensembles & “Going Away” Outfits: Molyneux specialized in elegant three-piece suits, day dresses, and tailored coats—perfect for women embarking on honeymoons, diplomatic missions, or extended tours via ocean liner.

Evening Gowns for Shipboard Events: Luxurious lamé and velvet gowns with low décolletés and clever draping reflect the formal dinners and dances held aboard ships like the RMS Aquitania, SS Ile de France, or the Olympic.

Functional Yet Chic Outerwear: His coats—lined in beaver, fox, or astrakhan—served both fashion and function as travelers moved between climates and social settings during transoceanic voyages.

For educators and students, Molyneux offers an ideal case study in how clothing adapted to mobile lifestyles and the changing role of women in the 20th century.

🌟 Most Engaging Content Highlights

👑 The Gown for the Sultana of Egypt

This luxurious gown, crafted in gold brocade with jeweled shoulder straps, was designed specifically for the wife of Sultan Fuad I. It’s an extraordinary example of cross-cultural diplomacy expressed through couture.

📷 Image ID #224bbe2509

🎭 Stage & Royal Patrons

Molyneux's clientele included Mademoiselle Hebe, the Hereditary Princess of Monaco, and leading ladies of French theatre—showcasing his global prestige. These links are perfect for students researching women in leadership, celebrity culture, or the fashion-theatre relationship.

🧥 Tailored Suits and Capes for the Traveling Elite

Descriptions of plaid coats, cape costumes, and fur-trimmed jackets are vital in understanding the wardrobe essentials for stylish travel during the 1920s.

🕊️ Evening Gowns with Detachable Trains, Capes, and Tunics

From black gauze draped with roses to hyacinth blue and gold brocade with double trains, Molyneux’s gowns were engineering marvels of movement, ideal for shipboard dancing and society receptions abroad.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images

“Characteristic Afternoon Frock of Molyneux” – (GGA Image ID #1cd3380e88)

A tunic design flattering all figures, emblematic of the soft power of feminine dress in postwar culture.

“Tailored Suit by Molyneux” – (GGA Image ID #1cd15211a7)

Practical yet regal, this ensemble illustrates the marriage of function and luxury so necessary for transatlantic travelers.

“Pearl-Gray Satin Gown with Petal-Like Overskirt” – (GGA Image ID #1cd2b12f79)

Delicate and sculptural, this gown reflects Molyneux’s mastery of cut and lightness—hallmarks of 1920s elegance.

“Cape Costume in Black Silk Jersey” – (GGA Image ID #224c087b87)

A modern masterpiece, complete with silver plaques and machine embroidery, proving the merging of technology and couture.

“Coral-Colored Panne Velvet Royal Robe” – (GGA Image ID #1cd50c532c)

Trimmed with pearls and large silver flowers—this gown evokes majesty without ostentation, ideal for formal cruise evenings or embassies abroad.

📘 Brief Dictionary of Terms for the Casual Reader

Crêpe de Chine: A lightweight, soft silk fabric known for its graceful drape.

Décolletage: The neckline of a dress, especially one that reveals the shoulders or chest.

Duvetyn: A soft, matte-finish wool fabric used for dresses and coats.

Ensemble: A coordinated outfit, typically including a dress and matching coat or accessories.

Fichu: A lightweight scarf worn around the shoulders, often decorative.

Matelassé: A thick, quilted or padded fabric with raised patterns.

Panne Velvet: A lustrous, flattened velvet fabric with a rich sheen.

Tailleur: A woman’s tailored suit, often part of a travel ensemble.

🎓 For Teachers, Students, and Researchers

💡 Students writing essays on 1920s fashion, travel culture, women’s independence, or Parisian haute couture will find this article rich in primary material and visual references. Consider exploring Molyneux’s designs in context with:

- The rise of international travel post-WWI

- Changing silhouettes and gender roles in the Jazz Age

- The influence of royalty and celebrities on popular fashion

📚 Encourage the use of GG Archives as a primary source repository. This article can serve as a starting point for museum-style fashion reports, comparative studies in design, or genealogical context for ancestors who traveled during the 1920s.