Georges Dœuillet: Parisian Couture, Travel Elegance, and Belle Époque Fashion (1908–1914)

📌 Explore the exquisite designs of Georges Dœuillet, the Paris couturier who defined elegance at sea and on land. From velvet reception gowns to satin bridal dresses, discover how his timeless fashion shaped the wardrobe of elite travelers during the ocean liner era. Ideal for teachers, students, historians, and genealogists.

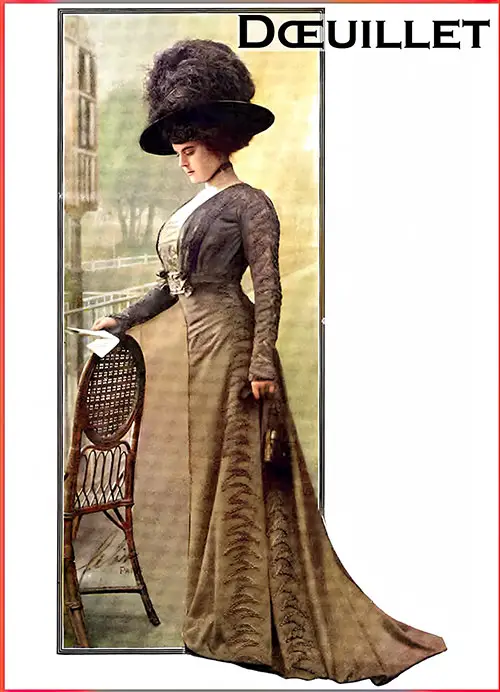

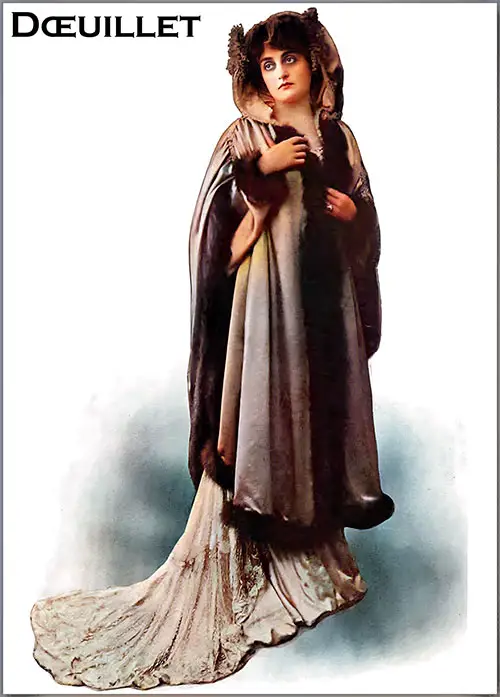

Exquisite Robe de Ville of Old Rose Heavy Satin, Embroidered With Soutache Braid - A Creation From the Establishment of Dœuillet. Silk Magazine, December 1908, p. 75. GGA Image ID # 1ca2fc7275

📌 Quick Facts: Georges Dœuillet

- Active Years: 1908–1914

- Specialty: Travel-ready couture, bridal gowns, velvet reception dresses, and elegant town gowns

- Signature Style: Quiet dignity, refined silhouettes, luxurious fabrics (velvet, satin, chiffon), and Orientalist & military-inspired details

- Clientele: Parisian elite, society brides, and first-class passengers on transatlantic voyages

- Historical Context: Belle Époque couture, bridging opulent late-19th century fashion with modern pre–World War I elegance

- Educational Value: Provides insight into women’s roles, social mobility, and cultural expectations during the ocean liner era

Georges Camille Dœuillet – The Parisian Architect of Elegance

Refined Fashion at the Crossroads of Travel, Society, and Design

🧵👗🛳️🎓

✨ Introduction: A Vision of Eternal Beauty

Georges Camille Dœuillet, one of Paris's most revered couturiers of the early 20th century, built a fashion house that combined timeless refinement with practical elegance. A favorite of the Parisienne elite and a trusted name for travelers and society brides alike, Dœuillet's creations were ideal for the transatlantic traveler, the upper-class hostess, and the fashion-forward modern woman.

Through detailed descriptions and stunning period illustrations, this article brings Dœuillet's couture masterpieces to life. Teachers, students, genealogists, and historians will find in this designer’s work a valuable window into fashion’s dialogue with gender, class, and luxury during the ocean liner era.

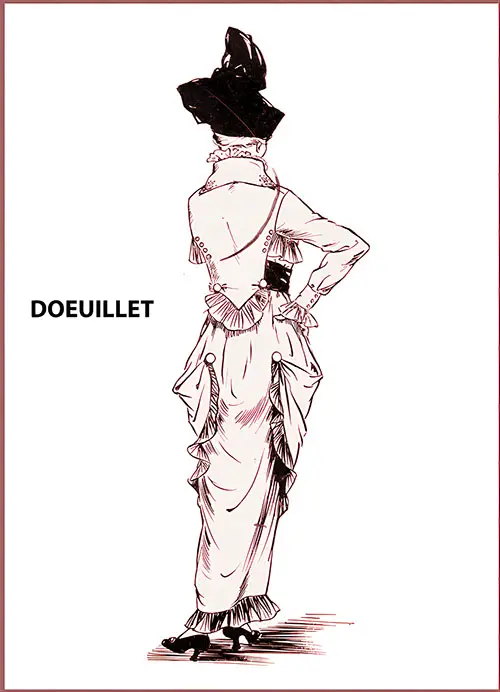

Robe de Drap Blanc Ajouré Modèle Dœuillet. Photo par Félix. White Open Cloth Dress Model Dœuillet. Photo by Félix. Revue des Français Supplement, 25 March 1911. | GGA Image ID # 217c4deb99

A Note of Quiet Dignity in Rendering the Most Acceptable of the New Fashions Results in Models of Elegance and Practicability. This is a signature style of Doeuillet, a renowned fashion designer known for his elegant and practical designs.

No matter how extreme the fashion, a quiet, distinguished note is characteristic of Doeuillet. His dresses are eminently wearable and adaptable to various occasions, not just theatrical effects.

There is no established style for tailleurs here, with different lines being equally shown. However, there is a preference for short, straight duvetyn, serge, or velvet models.

Dœuillet Makes a Feature of Velvet Gowns Similar to This Chocolate Velvet Reception Frock. The Skirts Are Formed of Double Tiers of Puffing, Giving an Extremely Bouffant Effect. The Waist Is Snugly Girdled With Blue Ribbon, and Over This, the Chiffon Blouse, With a Vest of Embroidered Chiffon, Hangs in Baggy Fulness. Harper's Bazar, October 1913, p. 27. | GGA Image ID # 1ca31b6cb7

Imagine the striking contrast of a red duvetyn coat, fringed with a playful monkey, paired with a black skirt. Or the elegance of a short black velvet jacket adorned with tiny red side pockets, worn with a plaid woolen skirt featuring raised lines of black and white. These are the fashion statements that are currently in vogue.

Their versatile fastening styles further enhance these short coats, a testament to fashion innovation. They can be buttoned up in front under numerous buttons, creating a sleek look, and can also form a flat cape at the back, just covering the sleeves, adding a touch of drama. A model showcasing this versatility is wearing a beige velours de laine. The skirt, with a couple of box pleats at the sides, and the collar, a seal scarf, complete the look.

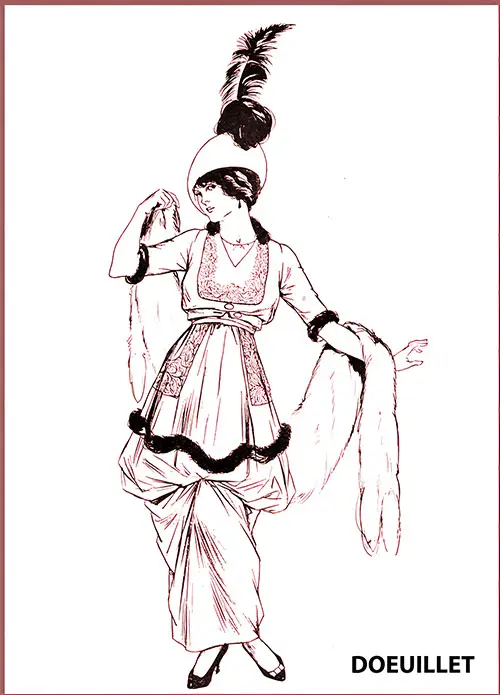

The Keynote of the Success in Dœuillet's Opening Lies in the Taffeta Frocks. And Much of the Novelty Is in the Tight-fitted Bodices, Loose and Full Through the Shoulders and Girdled by a Plain, Fitted Belt Buttoned in the Front. The Plaited Handkerchief Tunic, Pointed Down to the Knees in Front and Back, Has a Crush Rose of Velvet Adorning Each Point. Harper's Bazar, December 1913, p. 50. | GGA Image ID # 1ca40fea99

Discover the unique allure of the burnt orange sacking costume, a blend of simplicity and style. The skirt, meticulously pleated at the sides, and the straight jacket, adorned with delicate orange soutache embroidery, create a striking contrast. The ensemble is completed with a sealskin collar, adding a touch of elegance at the throat.

Step into elegance with the skirty three-quarter blue serge, a different type of fashion statement. Its many gores, each edged with a sleek black silk braid, create a unique silhouette. Complementing this, a very long mouse corduroy coat, opening over a squirrel's vest, adds a layer of sophistication to the ensemble.

Prepare to be captivated by the coat dresses, presenting their usual austere lines. Among them, a particularly striking and military model of red duvetyn emerges, boasting a high turned-over seal collar. The front is adorned with black and gold passementeries, reminiscent of the classic Brandeburgs, each ending in tassels.

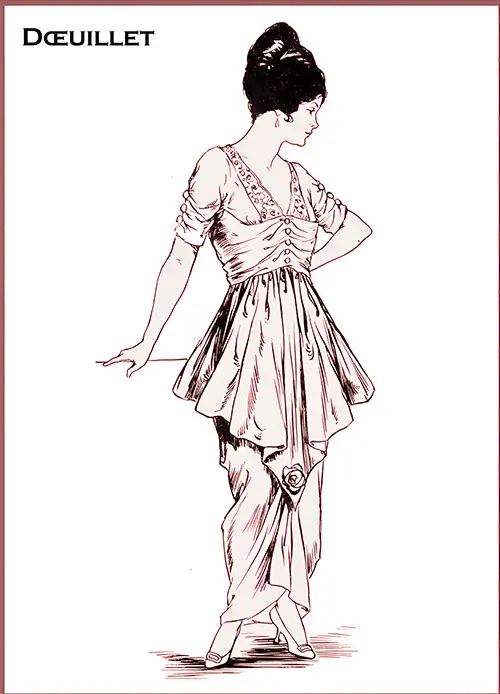

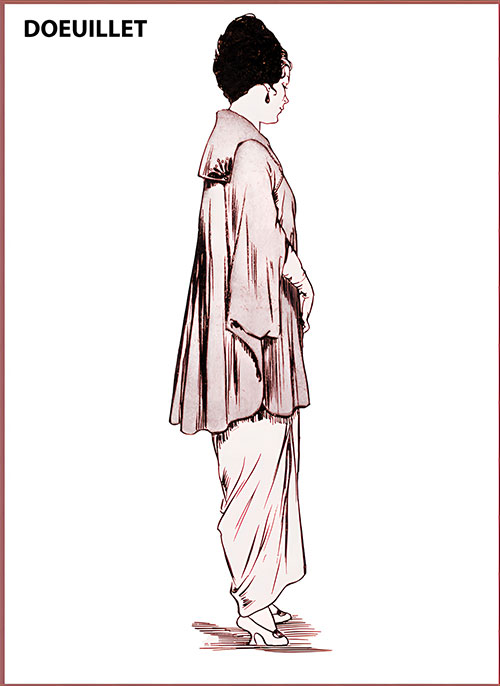

In Suits, Dœuillet Affects the Loose-backed Models Sloping to a Point Below the Waist and Outlined With Plaited Ruffle. His Skirts Are Plain in the Front, Gathered Slightly at the Belt, and Draped at the Hips in the Back. The Plaited Ruffle Emphasizes a Slight Flare at the Feet. A Blue Velvet Girdle and Silver Embroidery on the High Collar Denote the Directoire Influence. Harper's Bazar, December 1913, p. 50. | GGA Image ID # 1ca42d0ba8

Another long-waisted brick serge frock, the top worked in beads, with a vast beaver neckpiece with detached panels over the skirt caught at the hem.

The favorite model of black cashmere would be all perforated embroidery over white, and only each band is edged by a loose bias of the stuff, standing out.

The dress's outline is remarkable for its neatness and clarity. Even for the evening, no muslin capes or tunics blur the well-defined, sweeping silhouette. The panels used so extensively are often caught again under the hem.

Evening Gown by Dœuillet. Les Modes, May 1908, p. 5. | GGA Image ID # 1cb208c2ca

This Charming Creation From the House of Dœuillet Is Fashioned of Old Red Satin Lined With a Soft Pink a Pink So Pale in Color It Seems Merely Tinted From the Reflection of the Red. Silk Magazine, January 1909, p. 84. | GGA Image ID # 1ca30ca11b

Fur is rarely advocated, except for an occasional collar. Preferred fabrics are heavy enough to drape elegantly: velvet, moiré, brocaded satin, and thick, dull crepe marocain.

The Wraps, Whether for the Afternoon or for the Evening, Are in Cape Effect at Dœuillet's. This Model in Peacock Blue Broadcloth Hangs Straight and Full From the Neck With a Flare at the Bottom. The Draping Form the Sleeves Which Fall In Pouch-Like Lines Similar to the Oriental Garment . Silver Embroidery Trims the Collar. Harper's Bazar, December 1913, p. 51. | GGA Image ID # 1cdeca5c18

This afternoon dress is quite attention-grabbing due to its perfect line. It is made of black crêpe marocain with a waistline higher than the hips. The plain blouse features tight, long sleeves and buttons up the front to the high collar. At the back, there is a flat tunic that covers the back, but it is folded over in shell-like draperies at the hips.

The design is quite conservative, resembling a robe-chemise. A black velvet model opens over a pink duvetyn vest. The skirt's back and front are lined with the same pink fabric, detached but turned in at the hem.

Many wide, loose sashes mark the hip rather than the waistline. A loose sea-green moiré has one, as does the black velvet; only here, the belt is periwinkle blue. A band of many-hued embroidery, placed around the middle of the skirt, is repeated in a deep oval yoke.

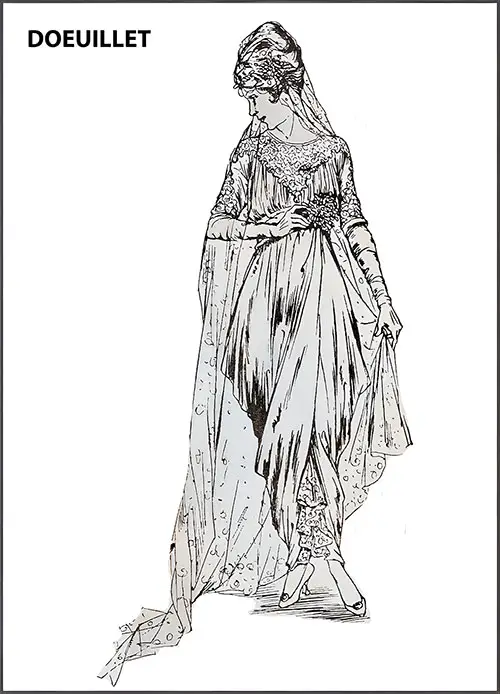

Dœuillet, Famed for Bridal Robes, Also Advises the Short Wedding Gown but Fashions It of Satin Cleverly Draped to Display a Beruffled Under Skirt of Lace Applique. A Berthe of the Lace Dresses up the Tucked Net Bodice. Harper's Bazar, May 1914, p. 54. | GGA Image ID # 1ca4309089

A beautiful dress made of dust-colored panne and chiffon features floating panels for a unique look. The upper half of the bodice is muslin, while the rest is panne. The square, foot-wide panels are muslin, hemmed in velvet. Both the blouse and tunic have fairylike embroidery of raffia disks and silk where the fabric joins.

For evening wear, there is a stunning collection of gowns draped in long sweeping lines. Chiffon, velvet, and panne are prominent, followed by metal fabric and beaded tissues. The best shades are silver, various mauves, and turquoise, which are most effective under artificial light.

The graceful, long sheath line, ending in a narrow double train, is executed in the palest mauve panne, cut low in a V. The front of the gown is extensively beaded.

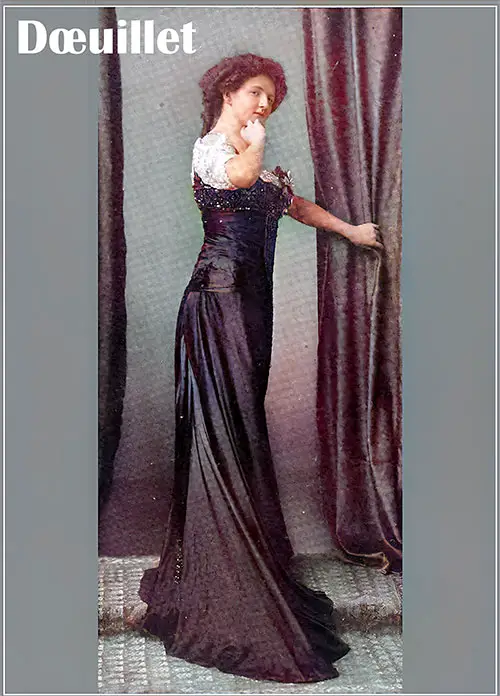

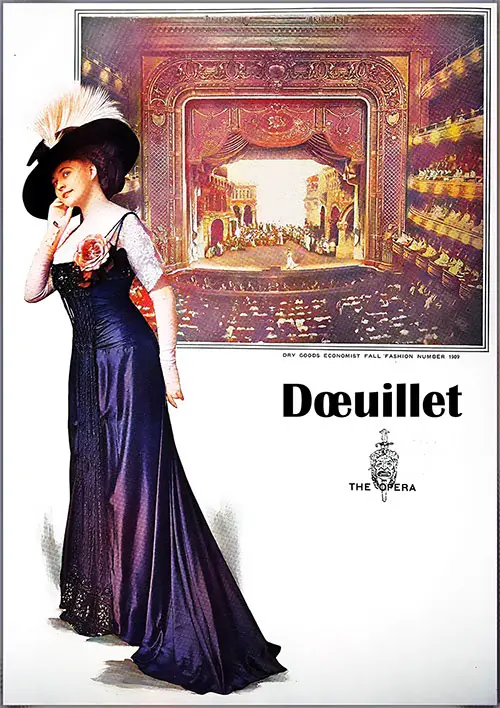

Black Satin Evening Costume, by Dœuillet. Dry Goods Economist, 17 July 1909, p. 5. | GGA Image ID # 1ca2a651f0

This model is particularly expressive of the dress of the high-class Parisienne. The house of Dœuillet is well known for its refined creations designed for women of high social standing.

The dress exemplifies the newest modes interpreted in typical Parisian fashion. The cut features a low waistline, and a peculiar arrangement of the draperies surrounding the torso compromises the pannier style and the low waist of the Moyen Age effect.

The material is black satin. The jet trimmings are slightly relieved with antique gold nail heads. A broad jet and gold band outline the low-cut bodice, and a novel panel of jetted net hangs the length of the front of the costume.

Black Satin Evening Gown by Dœuillet of Paris. Dry Goods Economist, 17 July 1909, p. 42. | GGA Image ID # 1ca2a959f2

The front of the bodice is adorned with a single large rose. The tiny sleeves and the décolletage of the bodice are of duchesse lace. This trimming, though extremely heavy in appearance, is lightweight. It is the hollow jet, making its use on sheer foundations possible.

The skirt is long and clinging, cut on circular lines. It falls over a foundation skirt of satin, which is very narrow and finished with a hem only, the idea being to accentuate the skirt's clinging drapery. The ribbon sashes are finished with pendant ornaments of jet and gold.

A sheath of a pointed jet is slit to the waist at the sides, showing a brocade foundation. In Egyptian design, a third straight model of gold and lamé is much longer in the back, thus forming a square train.

An idea that excited much interest was a low black velvet bodice worn with filmy lace over a gold lamé skirt. Velvet streamers or loops lined with gold, almost trains, established a connection between the two materials.

Velvet sheaths prove the foundation of many novel draperies. A silver cloth swathed over one side of a black fourreau ends in a wisp of a train; at each side hang loops of silver weighted down with jet. A deep turquoise blue pane is the lining, over which is thrown a pointed net tunic striped in iridescent beads.

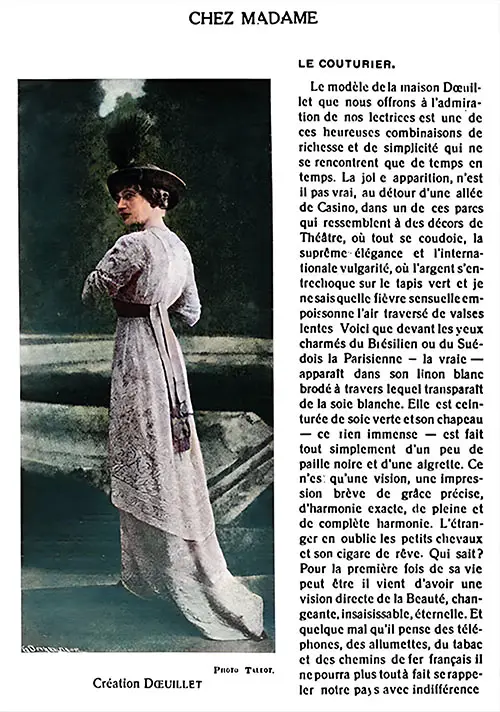

The Dress Is Adorned With White Muslin, Revealing White Silk Underneath. It Is Cinched With Green Silk, and Her Hat—a Large Trifle—Is Simply Made of Black Straw and an Aigrette. Created by Dœuillet. Photo by Talbot. Le Petit Mois Supplément illustré de la Revue des Français, 25 July 1912. | GGA Image ID # 218798992b

LE COUTURIER

Le modèle dela maison Dœuillet que nous offrons à l’admiration de nos lectrices est une de ces heureuses combinaisons de richesse et de simplicité qui ne se rencontrent que de temps en temps. La jol e apparition, n’est il pas vrai, au détour d’une allée de Casino, dans un de ces parcs qui ressemblent à des décors de Théâtre, où tout se coudoie, la suprême élégance et l'internationale vulgarité, où l'argent s’entrechoque sur le tapis vert et je ne sais quelle fièvre sensuelle em- poissonne l’air traversé de valses lentes Voici que devant les yeux charmés du Biésilien ou du Suédois la Parisienne - la vraie — apparaît dans son linon blanc brodé à travers lequel transparaît de la soie blanche. Elle est ceinturée de soie verte et son chapeau — ce rien immense — est fait tout simplement d’un peu de paille noire et d'une aigrette. Ce n’cs qu'une vision, une impression brève de grâce précise, d’harmonie exacte, de pleine et de complète harmonie. L’étranger en oublie les petits chevaux et son cigare de rêve. Qui sait? Pour la première fois de sa vie peut être il vient d’avoir une vision directe de la Beauté, changeante. insaisissable, éternelle. Et quelque mal qu’il pense des téléphones, des allumettes, du tabac et des chemins defer français il ne pourra plus tout à fait se rappeler notre pays avec indifférence.

THE FASHION DESIGNER (Translation of the French)

The model from the house of Dœuillet that we present to the admiration of our readers is one of those fortunate combinations of richness and simplicity that are only encountered occasionally. A lovely sight, isn't it, appearing at the turn of a Casino alley, in one of those parks that resemble theater sets, where everything mingles—the utmost elegance and international vulgarity, where money clashes on the green carpet and some sort of sensual fever poisons the air filled with slow waltzes.

Here, before the enchanted eyes of the Brazilian or the Swede, the Parisienne—the true one—appears in her embroidered white muslin, through which white silk can be seen. She is belted in green silk, and her hat—an immense trifle—is made simply of a bit of black straw and an aigrette. It is only a vision, a brief impression of precise grace, exact harmony, full and complete harmony.

The foreigner forgets the small horses and his dream cigar. Who knows? Perhaps for the first time in his life, he has just had a direct vision of Beauty, changeable, elusive, eternal. And no matter how much he might criticize the telephones, the matches, the tobacco, and the French railways, he will no longer be able to recall our country with indifference.

Bibliography

"Fall Fashions: Dœuillet" in the Dry Goods Economist, New York: The Root Newspaper Association, No. 3393, 17 July, 1909: 5-6, 42

"Le Couturier," in Le Petit Mois Supplément illustré de la Revue des Français, 25 July 1912: 11.

"Dœuillet" in the Garment Manufacturers' Index, New York: The Allen-Nugent Co. Publishers, Vol. II, No. 2, September 1920: 29.

🛳️ Relevance to Ocean Travel and Society

For first-class passengers aboard the Cunard Line or Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, fashion was not optional—it was essential. Dœuillet's creations were:

👒 Designed to be seen—on promenade decks, in salons, and at shipboard dinners.

✈️ Highly packable luxury—adaptable to the rigorous schedule of international travel.

🌍 Global in appeal—attracting Brazilian and Swedish tourists, as noted in one poetic article, symbolizing a Parisian ideal of grace.

His fashion house offered daywear, travel coats, dinner gowns, and bridal robes, making it a vital name in the wardrobe of the steamship society set.

🎨 Highlights & Noteworthy Content

👗 1. Exquisite Robe de Ville in Old Rose Satin | Image ID: 1ca2fc7275

Embroidered with soutache braid, this town gown evokes sophistication and understated glamour—ideal for city promenades or first-class shipboard tea.

🧥 2. Velvet Gowns & Short Coats | Image ID: 1ca31b6cb7

A chocolate velvet reception gown with puffed tiers and a chiffon blouse—romantic yet wearable. Short coats adorned with monkey fur and tartan skirts reflect Paris's flair for practical extravagance.

💃 3. Taffeta Frocks & Military Accents | Image ID: 1ca40fea99

Plaited handkerchief tunics and red duvetyn coats with black-and-gold passementerie highlight Dœuillet’s flair for the dramatic without sacrificing dignity.

👰 4. Bridal Robes & Afternoon Wraps | Image ID: 1ca4309089 & 1cdeca5c18

His satin wedding gowns, short yet ceremonial, showcase a delicate interplay of lace and drapery. Wraps hang like capes, with Oriental flair and silver embroidery—garments made to turn heads at a port arrival or embassy ball.

🖤 5. Evening Gowns in Black Satin & Lace | Image ID: 1ca2a651f0 & 1ca2a959f2

Masterpieces of silhouette: sleek skirts, velvet panniers, duchesse lace, and gold-trimmed bodices. The use of jet, lamé, and embroidery reinforces Dœuillet’s place as a master of material storytelling.

🧠 Brief Glossary of Terms

Berthe: Wide, flat collar made of lace or fabric.

Duvetyn: Soft wool fabric with a suede-like finish.

Fourreau: Close-fitting sheath-style gown.

Jet: A black gemstone or imitation used for beads or embellishments.

Moiré: Watered-silk fabric with a rippling visual effect.

Panne Velvet: Lustrous velvet with a crushed appearance.

Passementerie: Ornamental trimming, such as braids and tassels, often used on military coats.

Robe de Ville: Day dress suitable for urban or semi-formal settings.

Soutache Braid: Decorative flat braid used in embroidery and trim.

Velours de Laine: Plush wool velvet.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images for Research and Teaching

📸 Image ID | 📌 Description

- 1ca2fc7275 | Robe de ville in rose satin—elegance meets wearability

- 1ca31b6cb7 | Velvet reception gown with puffed skirt and blue ribbon girdle

- 1ca40fea99 | Taffeta frock with pointed tunic and velvet crush rose

- 1ca4309089 | Short bridal gown with lace-appliqued underskirt

- 1ca2a959f2 | Evening gown with lace décolletage and duchesse lace

- 1cdeca5c18 | Afternoon cape in peacock blue with Oriental draping

- 1cb208c2ca | Iconic muslin gown with green sash—a vision of French elegance

- 1ca2a651f0 | Black satin gown with Moyen Age–inspired pannier draping

These visuals make exceptional classroom aids for discussing dress silhouettes, luxury fabrics, and artistic couture from the Belle Époque to the Great War era.

🎓 Educational Value for Various Audiences

📘 For Teachers & Students:

🔹 Use Dœuillet’s fashion as a lens into social norms, femininity, and modernity from 1905–1915.

🔹 Assign design analysis essays: “Compare the silhouettes of Dœuillet and Lanvin” or “How did travel fashion reflect changing gender roles?”

🔹 Fashion programs can recreate patterns from his illustrations for pattern drafting and historical sewing assignments.

📸 For Genealogists & Social Historians:

🔹 Dœuillet’s designs are excellent references for dating family photographs, especially formal portraits of upper-class women.

🔹 His name, often associated with bridal attire, may appear in memoirs, travel diaries, or social pages linked to society weddings and voyages.

🧵 For Fashion Historians:

🔹 Dœuillet exemplifies the transition from Belle Époque structure to modern fluidity.

🔹 His embrace of Orientalism, military chic, and sculptural silhouettes offers fertile ground for exploring early modernism in couture.

💬 Final Thoughts – Why Dœuillet’s Work Still Matters

Georges Dœuillet did not simply dress women—he defined a cultural moment. His gowns whispered of restrained luxury, practical elegance, and subtle drama. For the first-class traveler, Dœuillet was both a comfort and a statement, blending wearable beauty with artistic form.

🌍 His work crossed oceans, social boundaries, and fashion epochs. In studying his creations, students and scholars gain access to the visual language of aspiration and identity that shaped the pre-war world.

📚 Encourage students to use this GG Archives feature in research essays on fashion, travel, or women's history. 🖨️📖🧵

✏️ Suggested Essay Prompts

- Fashion & Society: How did Georges Dœuillet’s gowns reflect the social expectations of women in the Belle Époque era?

- Ocean Travel: In what ways did fashion houses like Dœuillet influence the culture of luxury ocean liner travel?

- Comparative Analysis: Compare Dœuillet’s travel-ready couture with that of Jeanne Paquin or Callot Soeurs. What design choices distinguished his work?

- Global Perspective: Using Dœuillet’s designs, discuss how Parisian fashion shaped international perceptions of French elegance.

📚 How to Cite This Page

Chicago Style

Footnote:

Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives. “Georges Dœuillet: Parisian Couture & Ocean Travel Elegance (1908–1914).” GG Archives. Last modified September 14, 2025. https://www.ggarchives.com/OceanTravel/Fashions/FashionHouses/Doeuillet-ParisianCoutureRefinedTravelFashion.html.

Bibliography:

Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives. “Georges Dœuillet: Parisian Couture & Ocean Travel Elegance (1908–1914).” GG Archives. Last modified September 14, 2025. https://www.ggarchives.com/OceanTravel/Fashions/FashionHouses/Doeuillet-ParisianCoutureRefinedTravelFashion.html.

APA Style

Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives. (1908–1914). Georges Dœuillet: Parisian Couture & Ocean Travel Elegance. GG Archives. Retrieved Month Day, Year, from https://www.ggarchives.com/OceanTravel/Fashions/FashionHouses/Doeuillet-ParisianCoutureRefinedTravelFashion.html

MLA Style

Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives. “Georges Dœuillet: Parisian Couture & Ocean Travel Elegance (1908–1914).” GG Archives, 1908–1914. Web. Accessed Day Month Year. https://www.ggarchives.com/OceanTravel/Fashions/FashionHouses/Doeuillet-ParisianCoutureRefinedTravelFashion.html