London Fashions February 1888

By Mrs. Johnstone.

“Ladies have ladies' whims,' said crazy Ann, when she dragged her cloak in the gutter." So runs a Danish proverb, which teaches that opinions differ regarding the dictates of fashion.

The gift of "seeing ourselves as others see us" is frequently denied to those who follow the deed too closely; stout women would not favor huge checks, or tall women selecting stripes, nor would plump faces appear from beneath little bonnets.

The inspiration for Dress Designers

There is no excuse in the present day for wearing unbecoming garments. Dress-designers take their inspirations from every imaginable source.

In old times, the all-important question of the make of a gown had to be discussed with the dressmaker who produced only a few current fashion-plates while suggesting styles.

The many sources available at the time would come from old prints, photographs of famous pictures at various events and books of costumes of all ages and from all countries.

There is scarcely a famous female portrait of the Louis XIV, XV, and XVI periods in France that has not contributed its quota to current styles, nor stuff which the famous queens and courtesans of those days wore that we have not resuscitated.

Tea Gowns

Tea Gown

In the illustration of a tea-gown above, Mr. Sykes, of Regent Street, has taken advantage of Oriental types. The long sleeve through which the arm is thrust at the elbow, with pendant ends, has many a duplicate in Turkish harems.

The form of the belt and the tone of the embroidery savor also of the shores of the Bosporus, being very delicately worked in multi-colored beads and tinsel thread, displaying the mellowed tints of some Eastern carpet.

A pointed collar-piece duplicates the belt at the neck, which confines the soft fullness of the gathered Oriental silk, forming vertical folds, while at the skirt such folds fall horizontally. The "Princess" dress is made in plush or velvet.

It admits of many variations of color. Ruby, with a light pink front, harmonizes well with the class of embroidery employed; a galon to match borders the opening of the sleeve, and appears again as an epaulet, being carried up the shoulder in a point; a gold-broidered band encircles the throat.

This is a dress calculated to show off to the best advantage the graceful outline of the figure for which English women are known for. It is lined throughout with faint pink Surah, which shows as the wearer moves.

Tea-gowns would seem to gain favor increasingly. At country-house parties, they are universally worn at tea-time.

After a long walk in the lanes, or even after a long drive, it is delightful to cast off heavy woolen dresses, with thick boots, and don the easy, soft, flowing tea-gowns, which are at the same time becoming.

In London, they are the fashion for home dinner wear, and probably this is why they are made at all events to appear to fit more closely than they initially did.

It is not considered that they are in good style if in any way they suggest a dressing-gown or wrapper; and they are nearly all trimmed now with the costly tinsel galons, in which the metal gives just a sufficient feeling of metallic origin to assert itself without glitter, subduing and mellowing the tints.

Very beautiful tea-gowns appear on the stage, but perhaps the most splendid of all is that worn by Mrs. Bernard Beere in "As in a Looking-Glass," principally composed of red crepe, which swathes the limbs most gracefully.

She tears it open in the death scene, showing a white silk vest beneath otherwise invisible. Red tea-gowns are worn everywhere, but except for the embroidery upon them; there is no added mélange of color.

A leader of society has just ordered one in China crepe, trimmed only with a thick ruche of the same carried up the front and around the hem. The intricacies of draping involved in the arrangement of this particular gown, however, are altogether indescribable.

The Exquisite Ball Gown

In the fortnight previous to Lent, there promises a fair amount of gaiety. Something original and unlike the general style is what women most desire for a ball-gown, and this has been attained in the costume worn by the young girl in our picture shown below.

Ball Dresses

It is composed of the softest maize tulle, with a panel entirely made up of Gloire de Dijon roses without foliage, set as firmly together as possible; the panel widening towards the feet, and diminishing towards the waist, where it is united to a garland of the same roses in a single line; then crossing the bodice after the manner of a sword-belt.

This bodice is made in moiré, or peau de soie, which is real leather silk, that appears to be molded to the figure and never by any chance gives at the seams. It is cut square and has no other trimming save an ambitious bunch of flowers on the left shoulder — a universal fashion.

Where there are no flowers, they are replaced by bows of ribbon, or a feather aigrette, matching the “perky" little aigrette and bows, which are placed far back at the side of the head, so that they are almost invisible from the front.

The airier and gossamer these are, the more fashionable; and more often than not, they are formed of tulle, shaped as much like a butterfly as possible, with a tuft of osprey surmounting the whole. Young girls and matrons both wear them, the latter with as many diamonds as they can muster.

Occasionally a very tiny wreath of roses forms such an aigrette, and this would be appropriate with the rose-paneled gown, which has a row of roses and petals on the opposite side of the skirt, and a close ruché of roses at the feet in front.

This arrangement needs to be managed with great skill; the roses must nestle softly in a bed of tulle, and not stand out demonstratively, or they spoil the outline. With care they give that most necessary effect, a good appearance from the front, and show off the feet well, diminishing their apparent size.

Single sprays of flowers and detached petals scattered all over the tulle draperies are worn, and these also appear in the foot-ruchés. White is still the chief favorite, but tulle gowns are worn with the Baltique tone (the new and tender green), heliotrope in many shades (some, like fleur-de-Peche, are especially delicate and becoming), light pink, blue, and pearl-grey.

Dark tulles show off medium complexions best, and at the last Sandringham ball, where women generally dress exceptionally well, there were deep dark green, blue, brown, and red toilettes, the married ladies blending lace and brocade in addition to that.

The accompanying figure is a young matron, and as such wears, an elegant self-colored brocade dress intermixed with light pink tulle. The brocades of a uniform tone are newer than any other, and they rival the revivals of the Louis XVI period when drab and cream grounds showed small floral sprays in faint but natural coloring.

Such ball-skirts are cut wider than last year, and either the tulle falls in four or five layers, one above the other, or is mounted on satin, when one or at most two only are necessary, as the satin is allowed to show through.

Of course, the skirt must be bouffant at the back, cela va sans dire (that goes without saying); any indication of flatness is suggestive of dowdiness. The way the bunch of chrysanthemums is disposed on the skirt shows the natural way in which the flowers are worn; they should appear to be growing naturally, as they might do against a wall.

The little mantelette which accompanies this dress is made of pure white satin, with white ostrich feather trimming; it fits the figure, and comes below the waist, and cannot crush the tulle. It falls longer in front, but the ends are light, and will not destroy the airy freshness of the fabric.

It is much the sort of mantelette that was worn early in the century, often accompanied by a hood. The pure white hood contrasts charmingly with the delicate heliotrope tulle of the gown.

Fancy tulles of all kinds have come into fashion. These are beaded in many ways and embroidered in gold and silver. Everything will be silver this year, owing to the celebration of the Prince and Princess of Wales's silver wedding.

Newer in idea are the tulles with interwoven stripes, sometimes arranged horizontally, sometimes in such a way that the draperies are horizontal in front, perpendicular at the back, and diagonal at the side.

For many years, the artistic dressmakers have been teaching their lesson of a clever combination of tones, freedom of limb, and grace of outline, as well as redemption from the old conventional and undesired models; but for an exceptionally long time they have preached to deaf ears and found patrons only among a select few.

Now, however, fashionable modistes (who have hitherto ignored all but Parisian inspirations) are quietly adopting their ideas, and a successful picture-dress, according to the slang of the day, is what all desire to attain.

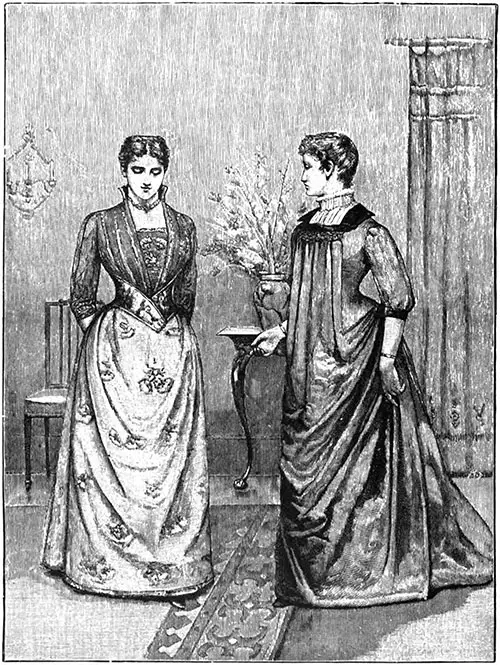

Artistic Dresses

Mrs. Nettleship, of Melbury Terrace, has been one of the most fortunate and famous pioneers of this new state of things, and the two dresses of her designing illustrated above have the great merit of absolute originality.

The first is made of a material which hitherto has been challenging to find, Indienne silk zephyr—a soft silky fabric not unlike grass-cloth, with a firm tenacity of thread peculiar to pure silk and rarely seen but in raw silk.

It is interwoven with gold in conventional and floral designs. In the present instance, the ground is of a delicate heliotrope, with floral sprays of gold all over; but the material is produced in beige, red, and other tones.

The waistcoat, introduced into the front of the bodice, is entirely composed of gold embroidery. It can be raised, if desired, in such a way as to form a high bodice with but little trouble; while the bodice itself is so soft and well draped that it can be drawn down to just the point of the shoulder, and thereby be made to look dressier.

A woman traveling with such a gown has a full dress or one for demi-toilette ready to hand, a mere touch of the fingers only being required to transform, and no tiresome tacking needed. Making one bodice do the work of two bodices has seldom been more skillfully met.

There are other points of originality in the gown. The skirt is caught up at the side with long ribbon streamers but has no distinct drapery. It is trimmed with gold galon worked on the stuff itself. The belt crosses, forming natural folds, being edged and decorated with gold.

If the wearer has a large waist, a darker shade than the rest of the bodice is chosen to diminish the apparent bulk. There is a square ruff-like collar at the back lined with a darker tone. This is the class of gown with which antique and uncommon jewelry can be worn —a point which those who make the dress a fine art are beginning to study.

The happy possessors of suites of amethysts, pink topaz, crocidolite, garnets, and other kinds of ornaments, which of late have not been much worn, are bringing them back to favor by having unique dresses made to go with them, thereby rendering them unique and perfect.

Uniformity is so well appreciated now!

The accompanying dress in our picture is made of dark and handsome silk brocade, with a velvet collar of a still darker tone, matching the band attached to the novel form of the sleeve, forming a wide turn back cuff.

This sleeve is gathered slightly into the arm, and is full at the elbow, giving perfect freedom of movement to the arm, and not in any way impeding the circulation, which cannot always be said of the coat-sleeve, often made so close fitting that the wearer could not comfortably raise her hand to her head.

The drapery is cut and arranged in quite an unconventional manner, being gathered to the front of the square yoke-shaped aperture, which can, by a smooth transition, be drawn up to the neck, where the side-lapels of velvet crossover at the throat.

A sash-belt may be added, defining the figure. The gown is throughout cut in one piece, the length and fullness being carelessly caught up at the back of the waist.

There is a new drapery for an upper skirt which is worthy to be described, being not only excellent in appearance but easily arranged. One long piece of the stuff is needed, the two front ends being caught up and turned back, forming paniers; these can be lined with a contrasting color or material; however, they fall well and easily about the figure.

The Watteau pleat is a revival of old days which has many patrons; but there is a new arrangement by which the center of this double pleat is allowed to droop, giving it an added grace borrowed from Greek examples.

Tucks are a natural addition to skirts, and tulle tucks are run with floss silk, which gives substance to the material, but mousseline de soie, colored crapes, and soft embroidered fabrics of all kinds are also tucked.

Panels of such materials so treated are often introduced now into the moiré bridal gowns, which open the entire length of the skirt to show this unique addition.

White cloth is, however, the newest idea for wedding dresses, and sometimes these are pinked and embroidered in pearls and silver, giving a most regal magnificence to the stuff.

Wadding is introduced into tucks and the edges of dresses generally, especially where the material is not very thick, and there is any likelihood of it clinging about the feet.

This is a clever idea, for it adds considerably to the importance of the skirt, and is not difficult to manage, even by amateur dressmakers.

Many morning and evening bodices made of soft stuff have the fullness kept in by bands of inch-wide ribbon at the waist, which cross each other, forming a couple of diamonds in the center of the front, thus diminishing the apparent size of the waist, which is one of the aims of a talented dressmaker.

Wool is the dominant material, but it is trimmed in such costly fashion, and so mixed with luxurious materials, that the gowns, mantles, and other garments of the day are by no means inexpensive.

Velours de laine is one of the new and costly stuff used for mantles, but it has so much to recommend it that the buyer is easily persuaded to the necessary outlay to possess it.

It is as soft as velvet and has a bloom upon it like a well-grown peach, being light and warm. It is made in various neutral tints. Brown tones are trimmed with furs and with gold ornaments, but the soft smoke-greys show best with beautiful black passementerie ornaments.

In arranging for the spring a redingote may be safely ordered, for it is the garment not only of the immediate future but also of the present. It looks best in velvet, or in some of the large-patterned woolen brocades, now that cloth is beginning to be considered too wintery.

Though in good truth, we have some of our coldest days in the spring, and we cannot do very wrong in ordering a habit cloth until April is well on its way. The redingote opens sufficiently in front to show the underskirt.

Johnstone, Violette, “February Fashions,” in The Woman’s World, Cassell & Company, Limited, London, Paris, New York & Melbourne, Volume I, No. 4, February 1888, p.185-188.

Editor's Note: Some terminology used in the description of women's clothing during the 1800s and early 1900s has been changed to reflect more modern terms. For example, a women's "Toilette" -- a form of costume or outfit has an entirely different common meaning in the 21st century. Typical terms applied to "toilette" include outfit, ensemble, or costume, depending on context.

Note: We have edited this text to correct grammatical errors and improve word choice to clarify the article for today’s readers. Changes made are typically minor, and we often left passive text “as is.” Those who need to quote the article directly should verify any changes by reviewing the original material.