Fashion Forecast for The Spring Season - January 1912

To write in the latter part of November an article for a January magazine to be sold in the book-stalls the early part of December is such a mixture of moods and tenses that it leaves one in some doubt as to seasons and seasonable subjects.

The date on the cover half convinces me that I have exchanged the Christmas stocking for the straw hat which the orthodox New Yorker puts on after New Year's with a fine disregard of furs and snowdrifts, and which for her is the first presage of the coming Spring.

Besides, the view which I get from my library—the naked, leafless branches of the trees, and beyond, the monotonous stretch of river lying gray and sodden beneath a pale, harsh winter sky-leaves me extremely skeptical as to any hope of warmer weather.

With each succeeding year, January is becoming more and more closely associated with Spring, not in the least owing to any change in climatic conditions, but to the fact that merchants and manufacturers begin to display their cotton materials as soon as their Christmas things are out of their windows.

Not as untimely a proceeding as one might think at first, since by the time New Year arrives, women have all the winter clothes they want or are going to get and are turning speculative eyes on the fashions of the coming season.

By January, the winter styles have been thoroughly tested and tried out, the failures have been given decent burial, while the successful models have been divided into two classes—the ones that belong distinctly to the Winter season and the ones that will carry over into the Spring season.

The longer coats that have been worn have been a pleasant change, but I| doubt if they hold for Spring. They will give place to the shorter jackets, and to the Etons, postilions and the little monkey-jackets as I call them—the coatees that are cut off just below the bust and which Callot made an unseasonable effort to bring in at the beginning of the Winter.

For all coats, the big collar and revers remain as popular as ever. Even the conservative morning hacking suit feels their influence and shows it in a reasonable enlargement of the revers of its notched collar.

For the semi-tailored suit, the square sailor collar or the pointed collar that runs down entirely to the waistline have proved the most suitable types. Just now, they are being made in fur-caracul on black velvet, moleskin on taupe, natural lynx on elephant gray.

Later, they will be made of lace or embroidery on silk and taffeta jackets. In many of our more straightforward suits, we have been using the two-toned materials I told you about earlier in the year, soft woolens woven in two broad strips of contrasting colors.

They have worked out very nicely—the second color serving for foundation skirts and collars. Some of these materials will undoubtedly reappear in lighter weights for the Spring, but I doubt if their second lease of life meets with much success, for they have been almost done to death this Winter.

The reversible coat is another popular favorite that I think has almost reached the end of its tether. Yes, indeed, we have them even on Fifth Avenue, and the multi-millionaires prates quite as loudly of their sound qualities as her Sixth Avenue sister.

I have made any number of them in fur lined with metal brocade. The fur makes a day coat which the light-colored brocade metamorphoses into a delightful evening wrap.

A fur coat with a silver lining does not sound precisely cheap, but when you consider that it is two coats in one, the silver lining justifies itself as something of an economy.

The law of compensation makes itself felt even in fashions, and in a season like the present when the new materials seem unduly extravagant, one has to remember that styles are considerately narrow and that brocades and velvets need minimal trimming.

I use more moleskin than anything else this year for coats and stoles and muffs. One of my most successful coat models is made with a deep kimono sleeved body of gold lace that comes down almost to the waistline.

The lower part of the coat is of moleskin, and in the back, it runs up in a point over the gold lace almost to the collar of taupe fox and tailless ermine. The collar is lined with self-colored silk brocade heavily figured with velvet.

I like the new long separate coats so much that I find it difficult to look at them quite dispassionately and admit their eccentricities, yet eccentric in cut they indeed are, with their deep kimono sleeves and large width through the body from the shoulders to the hips and the sharp intake at the knees.

They look as if they had been carefully planned to give a woman the figure of a top. Their width at the shoulder is only a little less surprising than their extreme narrowness at the bottom.

They look as if they clasped the knees so tightly that a woman could not walk in them, and it takes a tape measure to convince me that they are more than twenty-seven inches wide at the bottom. I see little to indicate any marked increase in the width of coats and skirts for the Spring season.

Rumors from abroad are that Paris has outdone itself in the matter of narrow dresses. I am none too credulous regarding such reports, for it is physically impossible to make skirts appreciably narrower than they have been, though much may be done to create that effect by bringing them in from the hip to the knee.

I think there will be no real change for the present, but when it comes, the drift must be toward greater rather than less width. One hears even now predictions or positive assertions of such a change, but I think they are because many French houses have moderated the extreme scantiness of their models while still keeping them narrow enough to be graceful.

Also, the use of soft materials and the present style of gathering almost everything at the waistline and draping up tunics and overskirts gives the impression that there is greater width than exists.

The waistline is still more or less of a wanderer, though many women are beginning to express a decided preference for the skirt fitted into the natural line of the figure.

On the other hand, there is excellent authority for the Empire waistline with no fitting at all between it and the hips. The raised waist certainly gives a woman height and fitting with the season after season in the face of changing fashions.

One new quirk in the present styles whose popularity proves either that it is not as shocking as it seems or that we are not as conservative as we like to fancy is the little trick of slashing the skirt at the bottom.

Of course, it is not carried to an extreme—the ankle or the shoe-top is as far as it goes - but women like it. I've had one very good suit model in black velvet with the coat and skirt trimmed at the bottom with shaped bands of caracul.

There is a slash about 10 inches deep at the left side of the front of the skirt. On one side of the slash, the skirt falls straight almost to the floor. On the other side, it is draped up, and the caracul runs up to the top of the slash holding the folds of the skirt in place.

I've carried out the spirit though not the letter of the slash in one of my evening dresses, and I've had to copy it any number of times. The original model was in a bright citron colored crepe meteor - the yellow silk draped the corsage of silver lace.

The skirt was quite plain and was caught up at the bottom displaying a rather deep flounce of the silver lace - entirely unlined and very fragile and transparent The feet and ankles showed through it very prettily, and it was more subtle and engaging than the actual slash.

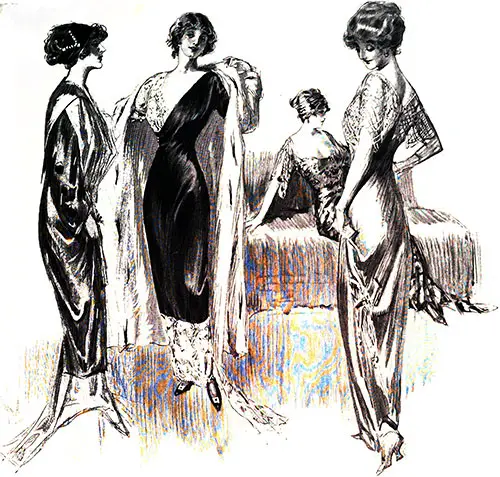

For my evening dresses, I am using principally brocaded silks and velvets. They are shamelessly extravagant, but they have the saving grace of being so beautiful in themselves that they can be cut very simply and call for almost no trimming. For day dresses there has been nothing that has taken place, for all-around utility, of black satin.

Velvet is more expensive and more pretentious. It is too much in a grand manner to be serviceable. Of course, it is popular, especially the black, taupe and changeable velvets.

For the Spring, silk serge, taffeta and to some extent silk poplin, will take its place. The latter material is new and very pretty, but it is also too expensive for everyday wear. It will be a silk season though, undoubtedly, for both suits and dresses.

There are one or two new colors or revivals of old colors that promise to be suitable for the Spring. Taupe, I think, will be quite as smart next season as it has been this.

Fortunately, it is not a color that can become common, for one only finds it in the materials of the better, more exceptional grades. All the shades of gray that range from mole to elephant's skin will be worn, and there are two or three new evening blues that are very lovely.

They come under the head of a royal, but I think lapis lazuli describes them more accurately. With gold or silver, they are incredibly brilliant, too brilliant indeed for the day, but most lovely under artificial light.

Lemon or citron is also a bright evening color; American Beauty is excellent in point of style and most helpful to almost anyone, for it brightens the dullest hair and complexion.

Black is still used with white, but more often with silver. I have just finished a dress of black brocaded in gold and made with one large revers of gold lace and the other of gold and turquoise bead embroidery.

The big revers are used on dresses quite as much as on coats, and many of them are so broad at the shoulders that they leave you in doubt as to the sleeve and armhole.

A good many sleeves are cut separate from the waist. Some are sewed into the lining, and some are joined to the blouse, giving the aspect of an armhole and yet retaining the useful features of the kimono sleeve.

In afternoon dresses a good many sleeves are long, but I only like the long sleeve in the dense, non-transparent materials. In chiffons and veilings, the long sleeve seems inconsistent and unpleasing.

The short sleeve is still in good standing and will undoubtedly gain ground again as the weather grows warmer.

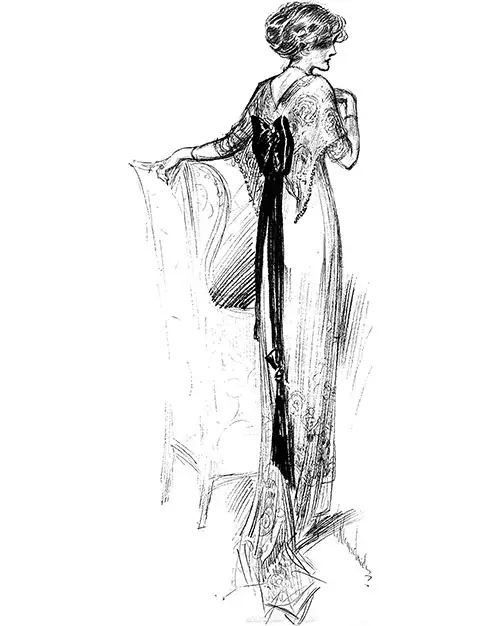

For some time I've wanted to talk to you on the subject of tea-gowns, for I think very few women outside of New York realize their full possibilities, and even here their vogue has been a comparatively recent growth.

Some of you, I've no doubt; class them entirely with the breakfast-in-bed habit and the boudoir. However, indeed, they are entirely too lovely to be kept in the bedroom. Most of them are quite suitable in cut and materials to be used for small semi-formal teas, dinners and bridge parties.

Of course, they would not be worn outside of one's own house, but inside they can make themselves extremely useful. Moreover, they positively are bewitching!

They are made principally of lace and chiffon, and when they are used strictly as breakfast-gowns, they are worn with adorable caps of lace and ribbon.

One of my very favorite tea-gowns is made of pale blue chiffon with a high-waistline jacket of cream-colored lace that comes down almost to the knees.

Another is in pale pink with a large square collar that reaches to the waistline in the back and comes well below it in front and is made of lace as fine as a cobweb.

Still, another is white chiffon underdress made on a satin foundation. The Overdress is of orchid-colored chiffon that shades from the palest lavender to a very deep mauve and is brocaded faintly in gold.

It is made with a deep bertha, edged with gold and purple ball fringe that passes over each shoulder and is caught into the high waistline in back with a big square bow of purple satin.

These tea-gowns are easily made, and I recommend them to the home dressmaker, for a while they are more fitted, of course than an ordinary negligee or room gown, they are not subjected to the rigid scrutiny that an evening dress has to undergo.

A certain softness, the merest suggestion of dishabille is permissible in them, and yet they answer the purpose of a tea and dinner dress in one, most of them are made to touch the floor all the way around.

Simcox, Clara E., "The Silver Lining: Points in the Present Fashions that Lighten Their Apparently Reckless Extravagance," in The Delineator, New York: The Butterick Publishing Company, Vol. LXXIX, No. 1, January 1912, p. 22-23.

Note: We have edited this text to correct grammatical errors and improve word choice to clarify the article for today’s readers. Changes made are typically minor, and we often left passive text “as is.” Those who need to quote the article directly should verify any changes by reviewing the original material.