The Wedding Ring in 1912 by Filomena

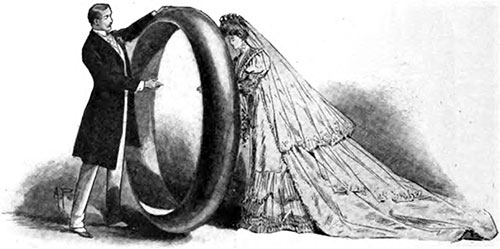

Illustration of a Consolidation of All Wedding Rings in the UK. The Strand Magazine (May 1907) p. 556. | GGA Image ID # 1032b02458

As soon as Lent is ended, weddings are numerous. Apropos, then, Professor Pollard, lecturing the other day at University College, London, professed to find in the wedding-ring a time-honored symbol of woman's subjection.

"He thought the ring had a common origin with the ring put in the nose of a wild bull; it implied control, captivity, obedience ." In a similar vein, the editor of Notes and Queries once asserted that the wife’s wearing the wedding ring on the left hand "implied obedience because the left hand is inferior to the right.”

I would suggest that wives instantly transfer their wedding rings to their right hands in token of independence, or eschew the ring altogether, so as not to appear like ”wild bulls under control.”

Such nonsense!

The ring can never have implied anything of the sort asserted; for, as a fact, it often used to be given in this country by the bride to the bridegroom, as well as vice versa, as it still is in Germany.

In the oldest form of wedding service used in Germany, the ”Service of Bishop Herman,” which is known to have been approved by our own early Reformers and to have had much influence upon the compilation of our English ceremonial at the Reformation, it is said: If the parties have brought rings for each other, these may now be put on”; and German men, to this day, generally wear plain gold rings in sign of their espousals. Much astonished would they be if compared to "wild bulls in captivity,” therefore The Prince Consort wore a wedding ring.

Some British husbands, too, methinks, would be safer going around the world thus marked "already booked.” Fascinating and flighty creatures, how well it would be to have them provided with a ring a piece, by no means on Professor Pollard's supposition, but merely, just as women are ”ringed,” to point out that they are no longer free for honorable courtship of or by the other sex—which is the purpose that common-sense indicates as the origin of the wedding ring.

As to the wedding-ring being placed upon the left hand, that again has an obvious, common-sense explanation. It is because the left hand is less actively employed than the right, and, therefore, a ring on the left hand is less in the way and less exposed to bending or injury.

But here again, there is no invariable rule; no common determination has been thus displayed by men to rivet and proclaim marital chains in a mystic meaning.

The Bride Wearing Her Bridal Jewelry of a Gold Ring and Pearl Necklace, The Jewelers Circular (18 June 1919) p. 74. | GGA Image ID # 1032bbb9e2

The ring, in the ancient ritual of England, was apparently placed upon the bride’s right hand at the altar. In the "Old Sarum” wedding ceremony, or "Use," which was the service most frequently followed before the Reformation, there is no word said about the left hand.

The ring was directed to be given to the bride together with other gold and silver; this was alluded to in a subsequent prayer—"As Isaac wedded Sarah, giving her bracelets and ornaments of gold and silver.”

The Eastern women now often keep their gold in the form of rings or bracelets, which are weighed and melted down if money is needed. Very likely the old English bride was not able to keep much of the other gold and silver offerings made to her by her husband at the wedding, but the ring was a fairly secure personal possession.

The English Puritan divines of the seventeenth century objected to the wedding-ring altogether; they called it pagan, because, apparently, it really had its origin in Roman customs. Somewhat curiously, the ladies of Catholic Spain, to this day, agree with those ultra-Protestants, our Puritan fathers, and generally dispense with the wearing of a wedding ring.

And again, the very antithesis of those strict Catholics, the English "Friends,” do not employ the ring in their marriage ceremony, though the Quaker wives usually, nowadays, follow the custom of the country by afterward wearing a plain gold ring as a sign of matron-age.

In old books, one finds a strangely inaccurate and imaginary reason for wearing the wedding ring on the fourth finger of the left hand. It is solemnly asserted that "By the received Opinion of the Learned and Experienced in Ripping up and Anatomizing Bodies, there is a Vein of Blood that passeth from the Fourth Finger unto the Heart, called Vena Amoris, Love's vein.”

Speaking of wedding-rings brings us very near to wedding-clothes, which will now be occupying the thoughts of Easter brides; and smart dressmakers tell us that young girls are choosing pure white, or white and silver; but it is with regret that we observe the passing of the old-time favored orange-blossom wreath.

To take its place, the foliage wreath in silver or gold is very becoming but does not have the same significance. Perhaps the most popular bridal veil is the Breton cap; the tulle, simply thrown over the head, is gathered into cap-shape and held in position by jeweled hairpins and a myrtle wreath.

Sometimes the veil over the face is dispensed with, and a wreath of tiny orange-blossoms or myrtle leaves, with their starry flowers showing up in the dark green of the foliage, hides the gathers.

"Ladies' Page," in The Illustrated London News, 20 April 1912, p. 586