Victims of the RMS Titanic Disaster

A Newspaper Boy in London Holds the Evening Newspaper, Splashing the Headline of 'Titanic Disaster. Great Loss of Life.' GGA Image ID # 1059eb71a3

The RMS Titanic claimed 1,503 lives on 15 April 1912 -- 832 passengers and 685 crew members, representing approximately 68% of the total souls on board of 2,208. The tragic loss of life was all but guaranteed as the Titanic had only 20 lifeboats with a capacity of 1,178.

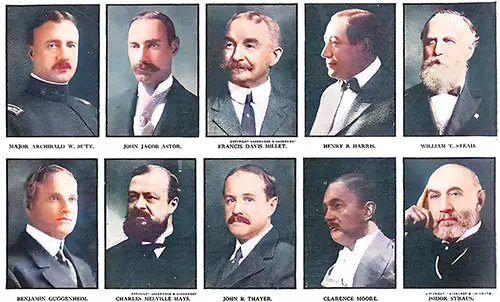

Distinguished Dead Among RMS “Titanic’s” Heroes

Photographs of Some Very Distinguished Men Who Died in the Titanic Disaster of 15 April 1912. Top Row: Major Archibald W. Butt, John Jacob Astor, Francis Davis Millet, Henry R. Harris, and William T. Stead. Bottom Row: Benjamin Guggenheim, Charles Melveille Hays, John B. Thayer, Clarence Moore, and Isidor Straus. Leslie's Weekly, 2 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 1029deac18

The men whose portraits are given here were among the many distinguished men who lost their lives in the "Titanic" disaster but who, in various ways, proved themselves of heroic mold before the climax of this greatest of marine catastrophes.

Major Butt, a trained soldier, died as bravely as one of his callings might have been killed on the field of battle. He helped many women and children to safety and, when last seen, stood rigidly at "attention," talking with Colonel Astor.

Many witnesses have related the stories of Colonel Astor's coolness, courtesy, and bravery. Isidor Straus endeavored to induce his wife to enter one after another of the lifeboats. Still, she refused to leave him, and they have clasped affectionately in each other's arms when last seen.

Henry B. Harris, the theatrical manager, after he had placed his wife in a lifeboat, stepped aside to let women pass to safety and awaited his fate.

Little has been told of William T. Stead. Still, like the others, he assisted in the terrible emergency and went to his death nobly.

Benjamin Guggenheim also displayed remarkable courage and consideration for others and met death without flinching. Charles M. Hays, President of the Grand Trunk Railway, was lost with and in the manner of the other courageous men.

John B. Thayer of Philadelphia, a Vice-President of the Pennsylvania Railroad, saw his wife safely in a boat and returned to help other women.

The exact circumstances separated Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Moore, and the husband met his fate alone.

Francis Davis Millet also went down with the ship. He was a noted artist, sculptor, and designer, a close friend and companion of Major Butt, and but recently had been made the president of the American Academy at Rome.

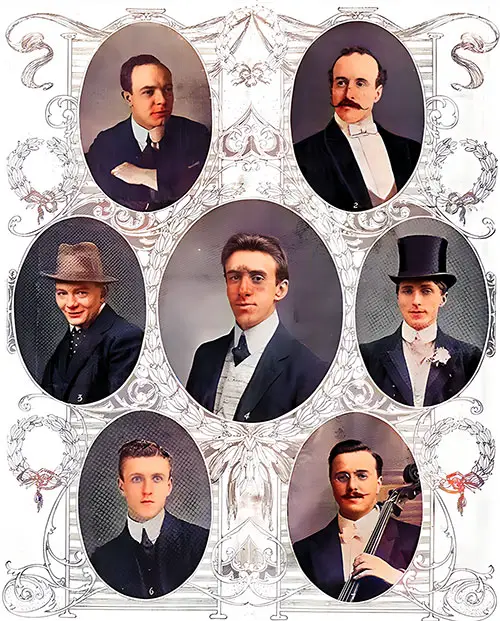

Musician Heroes Onboard the Titanic

RMS Titanic's Brave Musician Heroes - Led by Mr. W. Hartley of Dewsbury. The Illustrated London News, 11 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 101cf7267c

List of The Titanic Band Musicians

(Shown in the photograph above, top to bottom, left to right.)

- Mr. John Frederick Preston Clarke (28 July 1883 - 15 April 1912), Bassist (30) of Liverpool

- Mr. Percy Cornelius Taylor (20 March 1872 - 15 April 1912). Cellist (32) of Clapham

- Mr. Georges Alexandre Krins (18 March 1889 – 15 April 1912), Violinist (23) of Brixton, Sometimes of the Ritz Hotel Orchestra

- Mr. Wallace Hartley (Bandmaster), (2 June 1878 – 15 April 1912), Violinist (33) of Dewsbury

- Mr. Theodore Ronald Bralley (25 October 1887 – 15 April 1912), Pianist, 24, of Notting Hill

- Mr. John Law Hume (9 August 1890 – 15 April 1912), Violinist (21) of Dumfries

- Mr. John Wesley Woodward (11 September 1879 – 15 April 1912). Cellist (32) of Headington, Oxon

One of the most dramatic incidents of the great shipwreck was the heroic conduct of the band, which, led by Mr. W. Hartley of Dewsbury, continued to play up to a few minutes of the end.

There have been conflicting statements on this subject and others connected with the disaster. Still, of the central fact, there is no doubt.

In its careful summary of the various reports, the "Times" said: "That the band played as bravely as that other band in the 'Birkenhead 'during a great part of the time that the 'Titanic' was sinking seems indisputable . . .

"Nearer, my God, to Thee" and other hymn tunes were, as reported, played for some time. Then the music changed to something lighter (which would explain Bride's statement about the rag-time he heard) and continued until about ten minutes before the end.

As they played, the band-men are said to have tried to fix on life-belts. It may well be that it was not until they were flooded out that they gave up their heroic and self-appointed task.

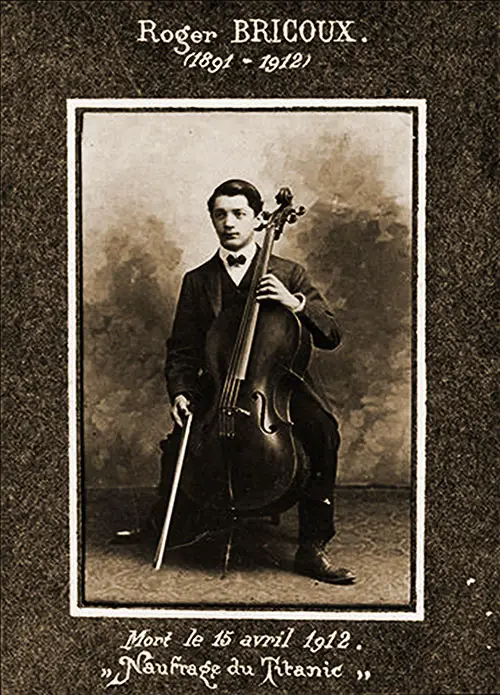

In addition to those in the photograph above, there was Mr. Roger Marie Bricoux (1 June 1891 – 15 April 1912), a Cellist (20) of Lille, France.

Photograph of Titanic Bandmember and Cellist Roger Marie Bricoux, 1891-1912. Mort le 15 avril 1912. "Naufrage du Titanic." GGA Image ID # 101d1cfa7e

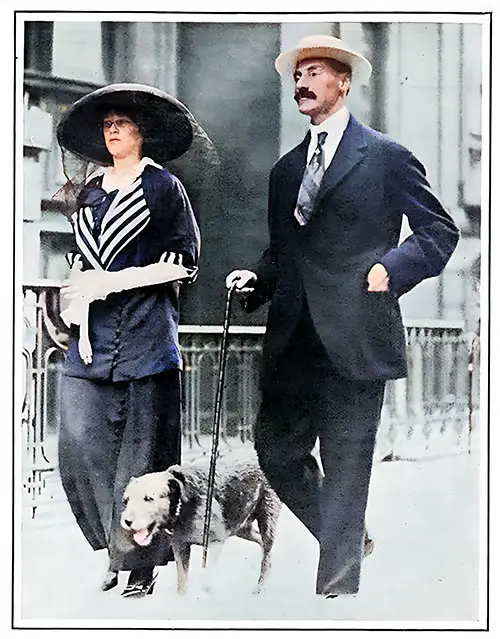

Colonel John Jacob Astor

Victim of the Titanic Disaster

Colonel John Jacob Astor with His Young Bride. Col. Astor Perished with the Titanic; His Wife Was Rescued. Sinking of the Titanic (1912) p. 161 Campbell Studios, New York. | GGA Image ID # 102dd47636

Mrs. Futrelle said she saw the parting of Col. John Jacob Astor and his young bride. Mrs. Astor was frantic. Her husband had to jump into the lifeboat four times and tell her he would be rescued later. After the fourth time, Mrs. Futrelle said, he jumped back to the sinking ship's deck, and the lifeboat bearing his bride made off.

"Many of the women did not seem to want to leave the vessel. Mrs. Astor clung to her husband, begging him to let her remain on the Titanic with him. When he insisted that she save herself, she threw her arms around him and begged him with tears to permit her to share his fate.

"Col. Astor picked her up bodily and carried her to a boat, which was the one just ahead of ours, and placed her in it.

"I lingered with my brother and his wife, reluctant to leave them, although we all knew the ship was sinking and that the ocean would soon swallow up all that remained of the steamer. We both begged my brother to come with us, but he said: 'No, I will remain with the others, no matter what happens.'

"Then, when it was time to go when the last boat was being lowered to the water line, we were hurried into it by my brother, who bade us goodbye and said calmly but with feeling: "Be brave; no matter what happens, be brave." Then he waved his hand, and our boat shot out just in time to escape, being borne down by the suction of the Titanic as it went down.

As the ship settled, a terrific explosion rendered it in two. As it sank beneath the waves, we could see my brother waving his hand to us, although it was hardly possible that he could see us, for none of us had a light. We had nothing except the clothes we had hastily donned. None of us had considered putting provisions or water in the boats, for we knew the Carpathia had been signaled to come to our rescue and was on its way.

"We heard several shots as the boats were being lowered, but we were told the officers were keeping the steerage passengers from stampeding into the small boats, which they repeatedly tried to do. "There were no outcries anywhere except from the steerage.

"I shall never forget the calmness and quiet bravery that the men on board showed as they stood on deck and awaited the inevitable doom. Occasionally, some would peer into the night toward our boats and wave at us. Then they would walk back to a group, and everything would grow still again.

"I saw Guggenheim, Widener, Thayer, and Ismay conversing with Colonel Astor just after the ship struck the berg."

A Mountain of Glass

Thomas Whitley, a waiter on the Titanic who was sent to a hospital with a fractured leg, was asleep five decks below the main saloon deck. He ran upstairs and saw the iceberg towering high above the forward deck of the Titanic.

"It looked like a giant mountain of glass," said Whitley. "I saw that we were in for it. I immediately heard that Stokehold No. 11 was filling with water and that the ship was doomed. The watertight doors had been closed, but the officers, fearing that there might be an explosion below decks, called for volunteers to go below to draw the fires.

"Twenty men stepped forward almost immediately and started down. To permit them to enter the hold, the doors needed to be opened again, and after that, one could almost feel the water rushing in. A few minutes later, all hands were ordered on deck with life belts."

John Jacob Astor, which has run for a hundred years through the commercial and social life of the metropolis, has taken on a new and nobler color in the passing of the last wearer of a famous name.

The last John Jacob Astor was a good soldier, sailor, inventor of note, a builder of stately public houses, an author, and a generous citizen. He was among the few rich men of the metropolis who gave their money and themselves to the service of their country. He equipped a whole battery of artillery and faced the bullets of the Spaniards at Santiago.

One of the wealthiest men in America, a leader of its ultimate social circle, newly married to a young and beautiful woman, John Jacob Astor had perhaps as much about him to make life sweet and to make death terrible as any man in all the great company of the Titanic.

And yet when the great moment came, he laid down his life as bravely as a soldier, as calmly as a philosopher, and with as sweet and quiet a philanthropy as if his days were without color and his years without hope.

If the John Jacob Astors of the century past have lived like princes, this one but yesterday died like a man.

And the great name he bore is better known and better honored for his life and death. The brave young wife who remembered others in mercy on that dreadful night has won the country's sympathy and respect.

Biography of Col. John J. Astor

Colonel John Jacob Astor and His Young Wife. Colonel Astor, millionaire and man of affairs was born at Rhine-Beck-on-the-Hudson on 13 July 1864 and became the chief representative of the Astor family in this country. The photograph shows him with his bride, formerly Miss Madeleine Force, whom he married last September and is reported as among the survivors. Harper's Weekly, 20 April 1912. | GGA Image ID # 109b0740b8

Col. John Jacob Astor, the American head of the Astor family, was born on the old Astor estate at Ferncliff, Rhinebeck-on-the-Hudson, on 13 July 1864. He was the son of William Astor and a great-grandson of the original John Jacob Astor, founder of the house. His early school days were spent at St. Paul's, Concord, N. H.

From there, he went to Harvard, graduating in 1888. Two years after his graduation came the announcement of his engagement to Miss Ava L. Willing, a noted belle of Philadelphia. They were married in 1891.

Two children were born to them, William Vincent Astor, now twenty-one years old, and Alice, ten. It was soon after this union that Colonel Astor began building large hotels.

The first of these was the Waldorf, later to be joined with the Astoria. Then came the St. Regis, Knickerbocker, and Astor. He also owned the old Astor House.

His title to Colonel was gained through his appointment to the staff of Governor Morton. At the outbreak of the war with Spain, he was among the first to offer his services to the War Department. He volunteered to raise and equip a battery of field guns and only asked that he be permitted to accompany it in some subordinate capacity.

His offer was accepted, and he was made a military inspector with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He accompanied General Shafter's expedition to Cuba and was in the boat that carried the General ashore.

The battery, organized and equipped at the cost of more than $100,000, was landed soon afterward, and Colonel Astor accompanied it throughout the campaign. During the assault on the Spanish lines at Santiago, the Astor battery was hotly engaged, and the Colonel was dismounted by a shell which killed the horse he was riding.

At the close of the war, he was warmly commended by General Shafter for "faithful and meritorious service," and the General urged that he be rewarded with the brevet rank of Colonel.

In September of 1911, Colonel Astor married Miss Madeleine Talmage Force, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. W. H. Force. Colonel Astor's fine new yacht, the Noma, was then in commission, and in this vessel, the two went on a bridal trip, which was extended to Egypt. They returned to London in time to take passage by the Titanic. Colonel Astor's city home was at No. 840 Fifth Avenue. His country estate was at Ferncliff.

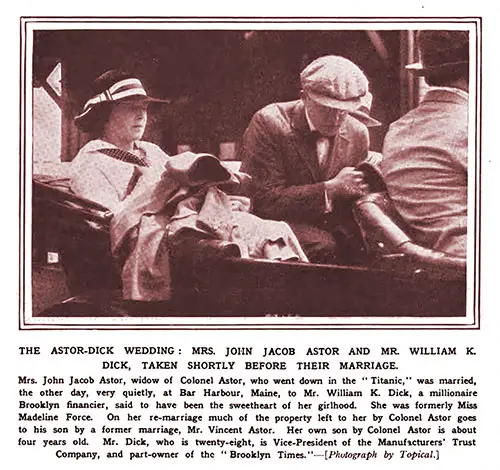

The Former Miss Madeleine Talmage Force (Mrs. Col. John Jacob Astor), who survived the Titanic disaster, went on to Marry Mr. William K. Dick, photograph taken shortly before their marriage by Topical. Mrs. John Jacob Astor, widow of Colonel Astor, who went down in the " Titanic," was married the other day, very quietly, at Bar Harbor, Maine, to Mr. William K. Dick, a millionaire Brooklyn financier, said to have been the sweetheart of her girlhood. She was formerly Miss Madeline Force. On her re-marriage, much of the property left to her by Colonel Astor goes to his son's former marriage, Mr. Vincent Astor. Her son, Colonel Astor, is about four years old. Mr. Dick, who is twenty-eight, is Vice-President of the Manufacturers' Trust Company and part-owner of the " Brooklyn Times." The Sketch Magazine, 12 July 1916. | GGA Image ID # 164f4f2c9b

Among the corporations and banks with which Colonel Astor was connected were the Astor Trust Company, Illinois Central Railroad, Mercantile Trust Company, Morton Trust Company, National Park Bank, Niagara Falls Power Company, Plaza Bank, Western Union Telegraph Company, Delaware and Hudson Railroad Company, New York Life Insurance and Trust Company, and Title Guarantee and Trust Company.

He was connected with nearly every club of prominence in the city, although he frequented a few. The clubs include Union, Metropolitan, Knickerbocker, Brook, Tuxedo, Automobile of America, Riding, Racquet and Tennis, New York Yacht, Army and Navy, and Turf and Field.

It is apparent, says the New York Tribune, that the sinking of the Titanic will cause the passing of vast fortunes from the hands that were to the successors who are. It adds:

Chief among these is the Astor fortune, variously estimated from $125,000,000 to $150,000,000. William Vincent Astor, the twenty-one-year-old son of Col. John Jacob Astor by his former wife, Mrs. Ava Willing Astor, will if the reports that Colonel Astor is among the lost prove true to be the chief heir of this vast estate.

In these days of trust fund executors who handle and keep intact fortunes for beneficiaries, it is considered unlikely that Colonel Astor will have turned over to his son the complete control of the Astor millions.

Speculation in the financial district yesterday was that the Astor money would go into a trust fund to be administered for the benefit of Vincent Astor and his sister, Ava Muriel, who was taken in charge by her mother when the first Mrs. Astor moved to London, following the quietly sensational divorce.

It is supposed by men who have followed the moves of the Astors that the first Mrs. Astor was abundantly taken care of both by prenuptial agreements and by the settlement made to her benefit when the divorce was granted. Their daughter, it is said, will, however, inherit enough of the vast estate to make her one of the richest of American heiresses.

Measuring Worth in Today's Dollars

The Astor Fortune, in today's dollars would be estimated at between $1.1 Billion and $85.3 Billion, depending on how you compare 1912 dollars to 2022 dollars.

In 2022, the relative values of $125,000,000.00 from 1912 ranges from $1,100,000,000.00 to $85,300,000,000.00.

A simple Purchasing Power Calculator would say the relative value is $3,890,000,000.00. This answer is obtained by multiplying $125000000 by the percentage increase in the CPI from 1912 to 2022. This may not be the best answer.

The best measure of the relative value over time depends on if you are interested in comparing the cost or value of a Commodity , Income or Wealth , or a Project.

If you want to compare the value of a $125,000,000.00 Commodity in 1912 there are four choices. In 2022 the relative:

- real price of that commodity is $3,890,000,000.00

- real value in consumption of that commodity is $8,370,000,000.00

- labor value of that commodity is $18,800,000,000.00 (using the unskilled wage) or $23,200,000,000.00 (using production worker compensation)

- income value of that commodity is $1,100,000,000.00

- economic share of that commodity is $85,300,000,000.00

If you want to compare the value of a $125,000,000.00 Income or Wealth , in 1912 there are five choices. In 2022 the relative:

- real wage or real wealth value of that income or wealth is $3,890,000,000.00

- household purchasing power value of that income or wealth is $8,370,000,000.00

- relative labor earnings of that commodity are $18,800,000,000.00 (using the unskilled wage) or $23,200,000,000.00 (using production worker compensation)

- relative income or wealth value of that income or wealth is $1,100,000,000.00

- relative output value of that income or wealth is $85,300,000,000.00

If you want to compare the value of a $125,000,000.00 Project in 1912 there are four choices. In 2022 the relative:

- real cost of that project is $2,760,000,000.00

- household cost of that project is $8,370,000,000.00

- labor cost of that project is $18,800,000,000.00 (using the unskilled wage) or $23,200,000,000.00 (using production worker compensation)

- relative cost of that project is $1,100,000,000.00

- economy cost of that project is $85,300,000,000.00

Samuel H. Williamson, "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1790 to present," MeasuringWorth, 2023. URL: www.measuringworth.com/uscompare/

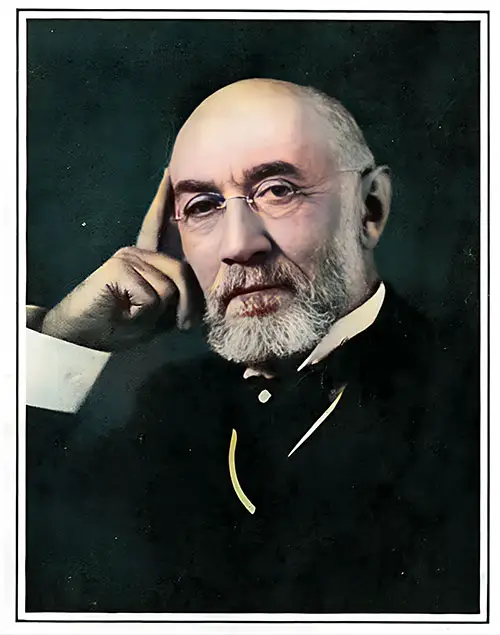

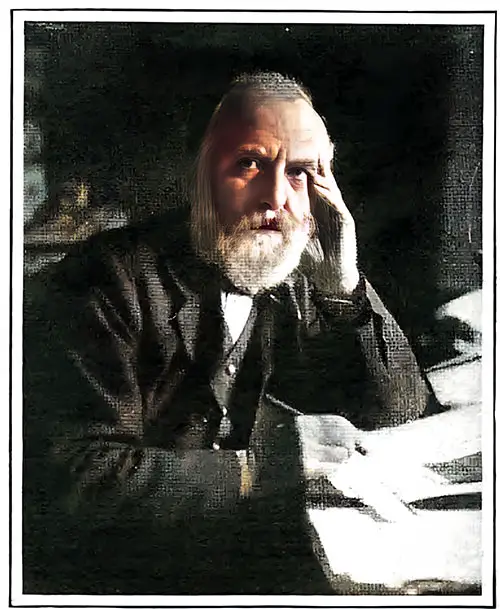

Isidor Straus: Victim of the Titanic Disaster

Titanic Victim Isidor Straus was born in Rhinish, Bavaria in 1845. He came to this country with his family when he was seven years old, and in his sixteenth year volunteered for the Confederate Army. Straus was rejected because of his youth and went to England, where he remained until the end of the war. After Mr. Straus return to America, he engaged in commerce and became one of the most distinguished of American merchants. Harper's Weekly, 20 April 1912. | GGA Image ID # 109bd20040

Besides being one of America's most successful merchants, Isidor Straus took an active interest in politics and sociological movements. The Tribune has this to say of his long and eventful life:

Isidor Straus, the eldest son of Lazarus Straus, was born in Rhenish Bavaria on February 6, 1845. At sixteen, he enlisted in a company of Confederate volunteers. He was chosen as a lieutenant, but the Confederate Government refused to accept him because of his age.

His first employment was a clerkship in a paper mill in Columbus, but he soon entered his father's store as a clerk. Two years later, he went to Europe as secretary for John E. Ward of Savannah, whom the Confederacy had dispatched abroad to purchase supplies for the army.

In 1864, Mr. Straus, for a while, was a clerk in the office of a ship-owner in Liverpool. In 1865, he joined his father in New York City to engage in the crockery business of L. Straus & Son.

In 1874, this firm enlarged its operations by taking charge of a glassware and china department, which R. H. Macy & Co. had opened in their 14th Street store. This successful venture resulted 1888 in Mr. Straus and his brother Nathan becoming members of R. H. Macy & Co. of New York, with Charles B. Webster as the senior partner. Under the new management, the various departments of the 14th Street store were multiplied.

For his active part in the campaign of 1892, on behalf of Mr. Cleveland, he was prominently named for the place of Postmaster-General, a place, however, for which he had no aspirations. He was led finally, in 1893, owing to the fight on the Wilson Tariff Bill, which was then at its hottest, being an ardent tariff-reformer, to accept a nomination at the special election in January 1894 for a member of Congress from the 15th District of New York, and, after a hotly contested campaign, was elected.

Mr. Straus was one of New York's leading philanthropists. The Educational Alliance, known as the "People's Palace," of the congested East Side tenement-house district, of which he was president, is a monument to his tireless interest in sociological reform. He was a director in several charitable organizations, regardless of creed.

Mr. and Mrs. Isidor Straus. The Truth About the Titanic, 1913. | GGA Image ID # 106f7da449

The Last Days of Mr. and Mrs. Straus

by Archibald Gracie

During this day, I saw much of Mr. and Mrs. Isidor Straus. In fact, from the very beginning to the end of our trip on the Titanic, we had been together several times each day.

I was with them on the deck the day we left Southampton and witnessed that ominous accident to the American liner, New York, lying at her pier, when the displacement of water by the movement of our huge ship caused a suction that pulled the smaller ship from her moorings and nearly caused a collision.

At the time of this, Mr. Straus told me that it seemed only a few years back that he had taken passage on this same ship, the New York, on her maiden trip and when she was spoken of as the "last word in shipbuilding."

He then called the attention of his wife and myself to the progress that had since been made by comparison of the two ships lying side by side.

During our daily talks after that, he related much of particular interest concerning incidents in his remarkable career, beginning with his early manhood in Georgia when, with the Confederate Government Commissioners, as an agent for the purchase of supplies, he ran the blockade of Europe.

His friendship with President Cleveland and how the latter had honored him were among the topics of daily conversation that interested me most.

On this Sunday, I recall how Mr. and Mrs. Straus were pleased about noon in anticipation of communicating by wireless telegraphy with their son and his wife on their way to Europe on board the passing ship Amerika.

Sometime before six o'clock, full of contentment, they told me of the message of greeting received in reply. This last goodbye to their loved ones must have been a consoling thought when the end came a few hours later.

From my conclusions and those of others, about forty-five minutes they had elapsed since the collision when Captain Smith's orders were transmitted to the crew to lower the lifeboats, loaded with women and children first.

The self-abnegation of Mr. and Mrs. Isidor Straus here shone forth heroically when she promptly and emphatically exclaimed: "No! I will not be separated from my husband; as we have lived, so will we die together," and when he, too, declined the assistance proffered on my earnest solicitation that, because of his age and helplessness, an exception should be made. He is allowed to accompany his wife in the boat.

"No!" he said, "I do not wish any distinction in my favor, which is not granted to others." As near as I can recall them, they addressed these words to me.

They expressed themselves as fully prepared to die and calmly sat down in steamer chairs on the glass-enclosed Deck A, prepared to meet their fate. Further pleas to make them change their decision were of no avail. Later, they moved to the Boat Deck above, accompanying Mrs. Straus's maid, who entered a lifeboat.

Isidor and Ida Straus

Who hereafter writes of Isidor Straus can fail to report of Ida Straus? Linked in a loyal life together, they were joined forever in noble death.

If Isidor Straus was a great merchant, philanthropist, clear-headed economist, and noble citizen, Ida Straus was a great woman, philanthropist, generous mother, and loyal, loving wife.

If Isidor Straus was the patriarch and honored head of a great family, Ida Straus was a distinguished home's serene and indispensable mistress. If Isidor Straus was a civic and commercial power, Ida Straus was a social and domestic force.

If Isidor Straus, after a life of honorable living, died a hero's death, then Ida Straus, after forty years of loyal loving, found a heroine's end of her choice. The beautiful examples of gracious living and a nobler dying meet in these remembered names.

In an age of material absorption, they have given a new and gentler illustration of the fidelity and tenderness of love. In an age of domestic disloyalty and divorce, they have wreathed a fadeless beauty around the deathless tie of marriage.

In life, they were united. In death, they refused to be divided. The world was better for their united living, so it shall be better for their loyal and undivided end.

Jack Phillips - Titanic Victim

Wireless Operator on the RMS Titanic

The death of Jack Phillips on the "Titanic," 15 April 1912, is, of course, familiar. Phillips remained at his post to the last, primarily due to his coolness and skill, so many were saved. Phillips was tired after a long vigil in the wireless room on the night of the disaster.

The machinery had broken down partly during the previous day, and Phillips had worked uninterruptedly for seven hours to repair it. Had Phillips neglected the work or had his skill been unequal to making the repairs, the fate of the "Titanic" might have been one of the sea's mysteries.

Early in the evening, the steamer hit an iceberg, and the captain requested Phillips to send out the distress signals. Several steamers were picked up, and Phillips continued calling. —The "Titanic's" signals grew fainter and fainter as the ship sank deeper into the water.

The captain ordered Phillips and Harold Bride, his assistant, to abandon the ship, but Phillips stuck to his post, calling for help. When he finally left his instruments, the last lifeboats had gone.

When the "Titanic" made her final plunge, Phillips was rescued from the icy waters by one of the crowded liferafts. Still, he died from exposure before help arrived.

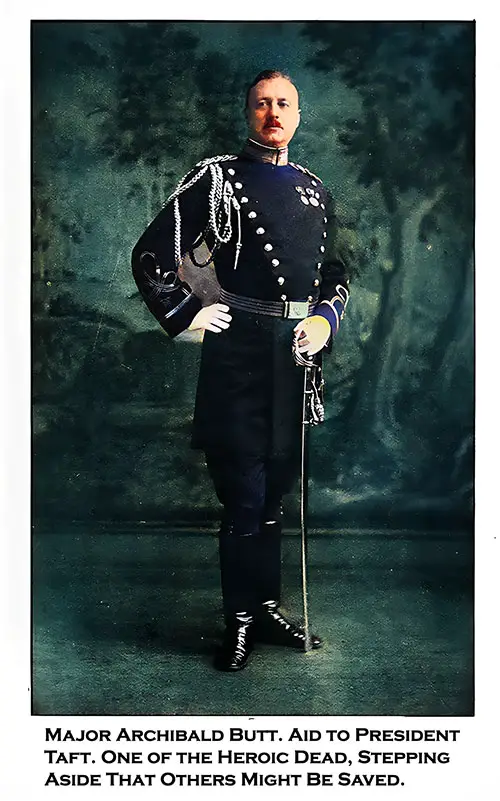

Archibald Willingham Butt - Titanic Victim

Major Archibald Butt. Aid to President Taft. One of the Heroic Dead, Stepping Aside That Others Might Be Saved. Photograph by Harris & Ewing. Wreck and Sinking of the Titanic, 1912. | GGA Image ID # 108dceec24

ARCHIBALD WILLINGHAM BUTT visited Texas, and the newspapers made him a target for many of their jokes. After his death on the Titanic, the Editor of the Houston Post published the following poem:

Archibald, Archibald, Willingham Butt

You have somehow made us feel like a mutt;

Always we've made you the butt of our jokes,

Always we've handed you giggles and pokes,

Gibed at you, jeered at you, laughed at you, took

A joy in just reaching for you with the hook;

Now, when we think of you, language is weak,

Now we sit here and with tears on our cheeks,

And a lump in our throat, and a hurt in our breast—

It was good-natured banter—naught but a jest—

But we'd give the world could we only recall

The gibes and the jeers and the giggles and all!

We shall see you forever till life shall grow pale

As you stood, hat in hand with a smile, at the rail

Of the ship as she sunk, with a cheery good-bye

To those, you had helped to the boats. In your eye

There was nothing to fear. Yours to strive and plan

For the weak, then to go to your death like a man,

With a smile on your lips and a call o'er the foam:

"Remember me, please, to the people back home."

Oh, the years of the world have been many and vast,

In each age of the world, there have been heroes who've died

For their fellows—whose deaths were impressive and grand,

But you—facing death with your hat in your hand

And a smile on your lips—oh, all language is weak!

There's a hurt in our hearts and a tear on our cheek!

God rest you, brave knight, in your sleep 'neath the foam,

You're enshrined in the hearts of us "people back home."

—Judd Mortimer Lewis in the Houston Post.

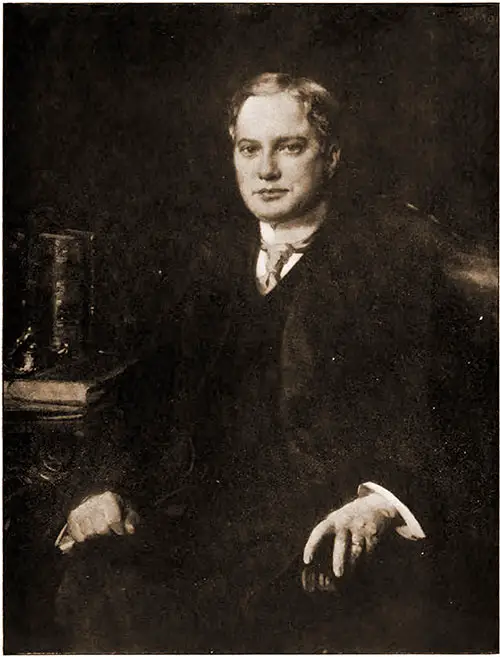

Titanic Victim Benjamin Guggenheim

Mining Machinery Executive

Benjamin Guggenheim Portrait Photograph - He was a Victim of the Titanic Disaster. © 1912 Marceau, NY. Power, 30 April 1912. | GGA Image ID # 10d4c931a8

Benjamin Guggenheim, who went down with the "Titanic," was born in Philadelphia in 1865 and is one of the younger of the seven sons of Meyer Guggenheim, who have become so prominent in the mining and metallurgical industries.

In the early 1880s, Meyer Guggenheim became a part owner of the A. Y. & Minnie mine at Leadville, Colo., which turned out to be profitable, and in 1885, Benjamin, just out of school, was sent to it to begin his business career and to look after the interests of his father, being given a position in the office.

During this period, he became acquainted with global mining and smelting conditions, especially from the commercial standpoint, and in 1888, through Edward Holden, he became interested in the smelting business and, in turn, interested his father and brothers in Philadelphia.

This was the inception of the Philadelphia Smelting & Refining Co., which erected works at Pueblo, Colo. In a very short time, the business passed wholly into the hands of the Guggenheim family, several members of which were sent to Pueblo to learn it.

The works were not very successful for two or three years, but before long, all of the difficulties were cured, and the brilliant commercial career in this business, with which all are familiar, was inaugurated.

The great success began in 1892 when the McKinley tariff checked the importation of Mexican lead ore. The Guggenheims immediately appreciated the possibilities of smelting in Mexico. They erected a plant at Monterey, followed by one at Aguascalientes.

Later, a refining plant was erected at Perth Amboy, N. J., under Benjamin Guggenheim's superintendence. After the smelting interests were consolidated, he retired from active work for a time, passing two years in Europe.

Returning to this country, he entered the mining machinery business in 1903, organizing the Power & Mining Machinery Co., which built significant works in Milwaukee.

In 1906, this concern was merged with the International Steam Pump Co., in which Benjamin Guggenheim was successively a director, executive committee chairman, and president.

This continued his primary business interest, and the visit to Europe, from which he was returning, was made to inspect and extend the work done through its foreign agencies.

-- The Engineering and Mining Journal, 27 April 1912, p. 827

The first definite information received of the death of Benjamin Guggenheim, whose life was lost in the going down of the ill-fated "Titanic" on 14 April, was acquired by his widow in a message from Mr. Guggenheim, delivered by an assistant Steward who was with him until a few minutes before the "Titanic" sank. The message was: "If anything should happen to me, tell my wife in New York that I've done my best in doing my duty."

In these words lies the keynote of Benjamin Guggenheim's whole life.

Benjamin Guggenheim was born on 26 October 1865, the fifth of the seven sons of Meyer Guggenheim, the founder of the great firm having mining interests worldwide. Young Benjamin, at 20, took charge of the company's mining properties in Leadville, Colo., and his cunning and energy are mainly due to the concern's success after years.

Later, he came East and managed a plant at Perth Amboy, N. J.

In 1903, Mr. Guggenheim erected a large machinery plant in Milwaukee, Wis., which was later merged with the International Steam Pump Co., of which he was elected president in 1909. With his brothers, he was also the controlling factor in the American Smelting & Refining Co.

Today, the International Steam Pump Co.'s products are limited only by the confines of industry in this country and abroad. It has seven plants, each significant in itself, which operate in the United States and one in England at Simpson. The company employs 10,000 men.

Mr. Guggenheim married Miss Floretta Seligman, a daughter of James Seligman, the banker, who survives him with three daughters.

-- Power, 30 April 1912, p. 643

It is the habit to speak of the days when young men of energy, industry, character, and brains could achieve brilliant business or professional careers in America and think such occupations are impossible now.

That they are unusual nowadays may be granted, but that they are possible can easily be proved. One of the striking examples of modern achievement in the industrial and financial world is that of the Guggenheim family, formerly of Philadelphia, where the founder, the late Meyer Guggenheim, settled many years ago and, starting for himself, built up a large and prosperous commercial business.

It is a remarkable fact that this fine old figure in the business community should have been succeeded by seven sons, all of whom have reached a plane of success that the father never dreamed of, not only in manufacturing, exploring, and commerce but also in finance and statesmanship. And how the family fortunes were diverted from commercial business, pure and simple, is little short of romance.

It was in 1885 that the father, Meyer Guggenheim, sent one of his three younger sons, Benjamin—then twenty years old—to Leadville, Colorado, to take charge of his mining interests, which at that time began to be enormously productive.

The A. Y. and Minnie mines became heavy silver and lead ore shippers. The products soon became essential to the smelting plants with which Mr. Benjamin Guggenheim naturally entered intimate relations.

Keen, far-sighted, and level-headed, as was his father before him, the young man studied the most advantageous methods of treating the ores. He foresaw with prophetic vision the tremendous possibilities of the smelting business.

He communicated his ideas to his father and brothers and, by his persistence and ceaseless urging, finally convinced them of the vast opportunities in the smelting of ores so that they were drawn into this line of industry and built their first smelting- plant at Pueblo, Colorado.

Soon after Mr. Benjamin Guggenheim got this in operation, the results were so satisfactory that his father and his six brothers decided to withdraw entirely from commercial business and devote their energies and abilities to the new and more extensive field.

Having abundant capital, unusual intelligence, and undaunted energy, they took the next step. They built a large plant at Agues Calientes, Mexico, where they first embarked on copper smelting and erected a third plant at Monterey, Mexico.

In the meantime, recognizing the desirability of refining the bullion produced at their various plants, they built a refinery at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Mr. Benjamin Guggenheim, the pioneer of the family in their Western operations, transferred his energies to managing the new refinery, of which he remained in charge for a lengthy period.

When the consolidation of the smelting industries was accomplished, the Guggenheim enterprises had become so large that they Were naturally the ruling factor in the American Smelting and Refining Company, and having seen his great object an actual reality, Mr. Benjamin Guggenheim went to Europe for a well-earned rest.

Returning a few years later, he looked for an individual field for his ongoing activities. He decided to enter into the manufacture of mining machinery. This was in 1903, and the large plant he built in Milwaukee at once became an element to be reckoned with.

Three years later, his Power and Mining Machinery Company was merged with the International Steam Pump Company. Mr. Benjamin Guggenheim has been a director and a large stockholder for years. Since then, he has been chairman of the Executive Committee of the International Steam Pump Company and was elected recently to the presidency.

Such, in brief, is the public career of a man only forty-four years of age who possesses bodily and mental strength, decision of character, extraordinary executive ability, and the courage to do things.

He is now devoting his entire time and energy to directing the affairs of the International Steam Pump Company, and at the present writing, is in Europe, visiting the company's plant near London and inspecting its various Continental offices, with the object of extending its extensive trade in foreign countries; for Mr. Benjamin Guggenheim has in active preparation essential plans for the expansion of his company's business and the extension of its present lines, as well as in new manufacturing enterprises.

Already the International Steam Pump Company has seven plants, six in this country and one in England, as follows: The Blake-Knowles, in East Cambridge, Mass.; the Deane, in Holyoke, Mass.; the Worthington, in Harrison, N. J.; the Snow- Holly, in Buffalo, N. Y.; the Laidlaw-Dunn- Gordon, in Cincinnati, Ohio; the Power and Mining Machinery, in Cudahy, WI.; and the Simpson plant in Newark, England.

An army of ten thousand men draws its sustenance from these great industrial workshops, whose product is infinite, from the smallest feed pump, weighing but a few pounds, to the enormous municipal pumping engine capable of supplying a city's mains with 20,000,000 gallons of water daily.

They supply the pumping apparatus and condensers for the battleships of the nation, pressure pumps for the cotton press of the South and the steel mill of Pennsylvania, the pumping engine that sends the crude oil on its long journey from the well to the refinery; the air compressor which makes it possible to work in caissons or tunnels under the bed of river and lake; the pumps that keep free from water the deep workings of the copper mine in Alaska or the gold mine in South Africa; the distributing pumps that transfer the products from one point to another in the brewery and the sugar house; the agricultural pumps that flood the rice fields in Louisiana and irrigate the fertile fields of the Nile.

The power behind the elevator, which takes you to the office in the tower in the skyscraper, is a steam pump. The company builds gas producers and gas engines in units up to the enormous prime mover of five thousand horse-power, which are destined to supplant the steam engine on account of their excellent fuel economy; it builds blast furnaces, cement machinery, mining, smelting, and milling plants for all metallurgical purposes, and incredible rock crushers used in the production of concrete and ballast.

In a word, the products of the International Steam Pump Company are limited only by the confines of industry and civilization. So, in the career of Mr. Benjamin Guggenheim, we find that this young man did not rest content after his splendid achievements in the smelting industry but turned his activities into another tremendous industrial enterprise, advancing it rapidly on its road to success. Our country of today is still rich in its offerings to those ready to give it their enthusiastic energy and untiring effort.

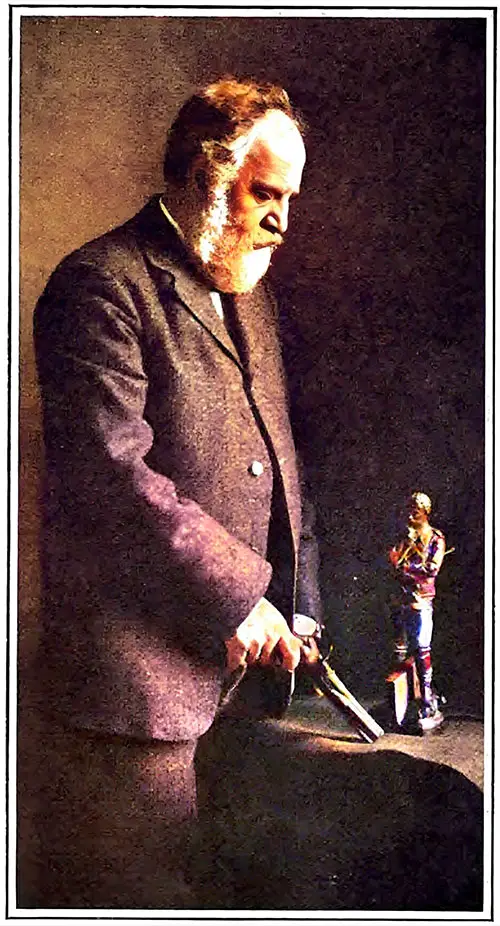

Benjamin Guggenheim, The New President of the International Steam Pump Company, New York, Reproduced from a Painting. Steam Magazine, April 1909. | GGA Image ID # 19f5bcbe1e

As noted in these columns last month, Benjamin Guggenheim, who for several years has been chairman of the Executive Committee of the International Steam Pump Company of New York, was elected president of the company two months ago to succeed John Dunn, who had resigned on account of ill health.

Benjamin Guggenheim, fifth of the seven sons of Meyer Guggenheim, is to credit for first turning the attention of his father and brothers to smelting, an industry in which the family has been a dominant factor for years.

When Benjamin Guggenheim was twenty years of age, he was sent to Leadville, Colorado, by his father to take charge of the elder Guggenheim's interest in a mine in which he had invested. He had been in Leadville briefly when he recognized the possibilities in the smelting business. This young man's keen foresight started the Guggenheim family in that business. This business has made a more significant part of their vast fortune than any other of the various branches of industry in which they have excelled.

Benjamin Guggenheim's urging caused his father and brothers to build their first smelting plant in Pueblo, Colorado. He took charge of this plant and conducted it with such pronounced success that the family finally withdrew entirely from commercial business and devoted their energy and ability to the smelting industry.

Benjamin Guggenheim has devoted his life since his twentieth year to hard work, and, like the other members of this remarkable family, he has been unusually successful. He was born in Philadelphia in 1865 and received his early education in the public schools in that city—his father. Meyer Guggenheim founded the famous house of M. Guggenheim & Sons. Who came to America from Switzerland in 1848 and started in business in a small way.

The development of the smelting industry in this country is a part of the story of the Guggenheim family. Still, a significant share of the credit must go to Benjamin. Their success in Colorado led to the building of plants at Aguascalientes, Mexico, and Monterey. Mexico, and an immense refining plant at Perth Amboy, N. J. Benjamin Guggenheim took charge of this latter plant. They managed it for several years.

After the consolidation of the smelting industries was accomplished, the Guggenheim interests had become so large that they were naturally the ruling factors in the American Smelting and Refining Company, and. having seen his great object an actuality, Benjamin Guggenheim went to Europe for a well-earned rest.

Returning a couple of years later, he entered the manufacturing business. In 1903, he built a large plant in Milwaukee. Wisconsin, for the manufacture of mining machinery.

Three years later, the power and machinery company was merged with the International Steam Pump Company. Mr. Guggenheim had been a director and a large stockholder for several years.

He became chairman of the executive committee of the merged company. He served in that capacity until he was recently made president of the company. He is now devoting his entire time and energy to directing the affairs of the International Steam Pump Company.

He is at present in Europe, visiting the company's plant in England and inspecting its various continental offices with the object of extending its extensive trade in foreign countries.

Already the International Steam Pump Company has seven plants, six in this country and one in England, as follows:—The Worthington, in Harrison, N. J.; the Blake-Knowles, in East Cambridge, Mass.; the Deane, in Holyoke, Mass.; the Snow-Holly, in Buffalo, N. Y.; the Laidlaw-Dunn-Gordon, in Cincinnati, Ohio; the Power and Mining Machinery, in Cudahy, Wis., and the Simpson plant, in Newark, England.

Mr. Guggenheim has in active preparation plans for the expansion of his company's business and the extension of its present lines as well as in new manufacturing enterprises.

William T. Stead, Titanic Victim

By Albert Shaw

When the pages of this Review were closed for the press last month, it was practically sure that William T. Stead was not one of the rescued survivors of the Titanic. There was a bare chance that a few passengers had been picked up by sailing vessels of the fishing fleet off the banks of Newfoundland, but this faint hope was proved futile after a few days.

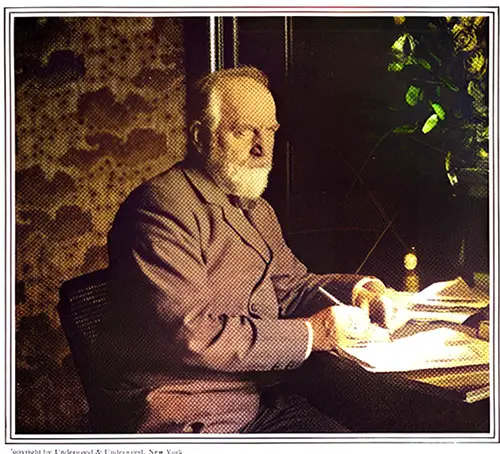

William T. Stead. The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. Photograph by Underwood & Underwood, New York. | GGA Image ID # 10558fbcc8

Some days before the great ship sailed, Mr. Stead, in the course of a letter to the editor of this magazine, had written as follows:

The general feeling of unrest surging worldwide just now is profoundly disquieting many minds. However, it is raising high hopes in others.

Mrs. Besant, with whom I am launching today, is very confident that the signs of the times foreshadow the second coming of the Divine incarnation. At the same time, there is a general conviction in the other camp that the end of all things is near.

It is a mighty exciting time, although somewhat trying to calm one's nerves. We have enough coal in our house to last another ten days, and then we are done. If things settle into something like decent order here, I should start for New York on the Titanic, which sails, if it can get coal enough, on April 10.

It will be her first voyage, and the sea trip will do me good, and I shall have a chance to see you all for a few days. I should not remain in America for more than a week.

With its profound social and political bearings, the great coal strike had engaged Mr. Stead's time and attention. No one grasped its significance more fully and wrote about it with more complete knowledge or a clearer understanding of its meaning than he did.

His sympathies were firmly with the solution reached by an act of Parliament. His interpretation of the meaning of that solution will be found in five pages from his pen that came to us in time for use in the May number of the REVIEW and which we published under the title: "A World's Object Lesson from British Democracy."

England had put into her laws and social institutions two new principles: the minimum living wage as a human right and the settlement of industrial deadlocks by government action when the whole public welfare is involved.

It was characteristic of Mr. Stead that he should have gloried in a solution that, to his mind, meant much for improving general conditions. For forty years as a journalist and reformer, he had been working with pen and voice for the upbuilding of the British democracy. And he had toiled with the completeness of faith and a single-minded intensity of conviction that made him even more the prophet and the preacher of righteousness than the great journalist.

Yet no man of his time had a better knowledge of the art and method of journalism. In using the press as the organ of modern democratic opinion, he was almost, if not entirely, unequaled.

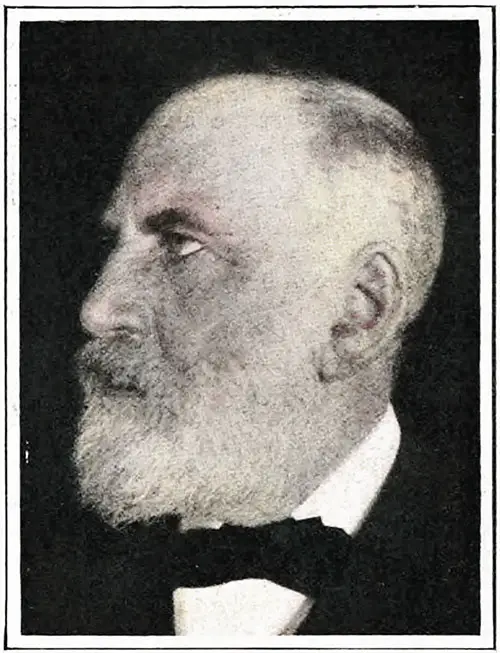

Portrait Photo of the Veteran Journalist, Mr. William T. Stead. The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. | GGA Image ID # 10571d31b6

Mr. Stead had begun his journalistic career while still very young. His father was a Congregationalist minister in the north of England, and the family income was too small to give the promising son a university education. But his father was able to provide him with something far better, for he inspired his boy with great intellectual, moral, and social ideals.

A more eager mentality than young Stead could not have been found in the realm. His reading was well-directed and voluminous, his memory was prodigious, and a certain amount of schooling sufficed to give some discipline and direction to his further work of self-education.

As a means of self-support, while still in his teens, he entered a business establishment but constantly wrote for the local press. This writing was so original and robust that it led to his appointment as editor of a daily paper called the Northern Echo, published at Darlington, near Newcastle-on-Tyne, when he had scarcely more than entered upon his majority.

This was in 1871, and his work at Darlington continued for nearly ten years. It was during this time that Mr. Gladstone aroused the conscience of England by his attacks upon Lord Beaconsfield's Government for its complacent attitude toward Turkey in the matter of the Bulgarian atrocities.

Great leaders in church and state rallied about Mr. Gladstone, and no one wrote on behalf of the persecuted Bulgarian Christians more earnestly and brilliantly than W. T. Stead. His work brought him recognition, and he was regarded as a man with a future.

His association with the leaders in this work that supported Russia in her campaign against Türkiye and brought Mr. Gladstone back into power led to his removal to London.

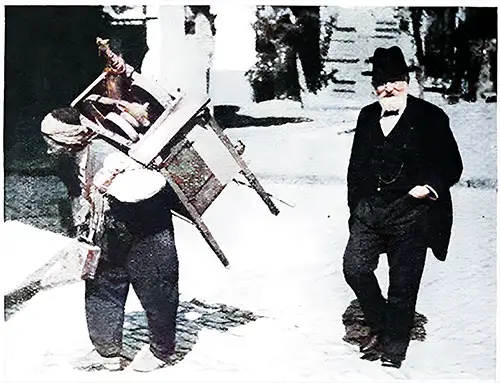

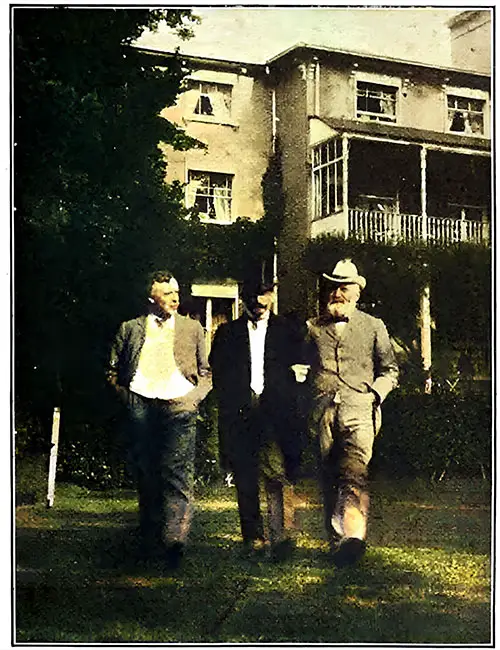

Mr. Stead is on Vacation at Hayling Island. Mr. Stead had some years ago acquired a summer home, which he called Holly Bush, on the south coast of England, at Hayling Island, where with his family he threw himself with great zest into out-of-door recreations and where, also, he did much of his writing. The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. | GGA Image ID # 10576bc252

In 1880, Mr. John Morley, now Lord Morley, became editor of the Pall Mall Gazette. Mr. Stead was invited to become his assistant editor. Mr. Morley, after two or three years, went into Parliament and gave up the editorship, Mr. Stead being appointed to succeed him.

At this point, great things happened in London journalism. Mr. Stead put amazing energy and fertility of resources into his editorial work. He surrounded himself with young men of talent and brilliancy who helped him make the paper the most alert and engaging in England while also leading its contemporaries in intellectual and literary qualities.

In those days, Mr. Stead's sensational but well-informed work achieved the reconstruction of the British navy. The Pall Mall Gazette led in every field of moral, social, and political progress. It was the apostle of friendship rather than hostility between England and Russia.

Mr. Stead in Constantinople last autumn (1911). The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. | GGA Image ID # 10578ef086

Its daring exposure of conditions under which young girls were forced into "white slavery" led to the enactment of better laws and permanent social reforms. However, Mr. Stead went to jail for three months on a technical charge resulting from methods used by his assistants to obtain evidence.

Meanwhile, Mr. Stead had established interviewing as a feature of London journalism, and he was the most remarkable interviewer yet produced by the modern newspaper. His interest was so intense, his intelligence so alert, and his memory so impressive that he could transmute a conversation in which no notes were taken into an extended report of almost flawless accuracy.

As an illustration of his methods at that time, a personal incident may be related. The present writer, then a young Western editor, had been spending the more significant part of the year 1888 in England, where his opportunities for observation and study had been due in large part to the friendship of Mr. Bryce—then in Parliament and now ambassador at Washington—and the late Sir Percy Bunting, editor of the Contemporary Review.

Mr. Bryce and Mr. Bunting had repeatedly advised the young American that he must know Mr. Stead as the most active and potent personality in English journalism, even though, in their opinion, somewhat stubborn and prone at times to kick over the traces of the Liberal party, of which they were prominent members.

An introduction to Mr. Stead led to an immediate invitation to spend the night with him in his suburban home in Wimbledon. The first impression made by the Pall Mall editor was that of an astonishing vitality and energy. Though like a whirlwind in getting the last forms of his afternoon paper to press, he was practical and methodical despite the rapidity of his mental and physical movements.

Arriving at Wimbledon in the autumn twilight, Mr. Stead sprang into a swing suspended from the branch of a great tree behind the house. He swung himself violently back and forth until he had satisfied his need for exercise and fresh air.

After dinner, he led the visitor into a narration of what had seemed novel and vital to an American familiar with the problems of American cities in the new undertakings that were transforming Glasgow.

Two or three days later, a package of proofs was mailed to the American's London lodgings. Mr. Stead had cast the conversation into an interview on the social reforms of the municipality of Glasgow, which was so complete and accurate that only a few corrections were needed.

It was so long that it was broken into two parts and appeared in successive numbers in the Pall Mall Gazette. Although editor-in-chief of the paper, Mr. Stead gave his personal touch to any and every detail. Perhaps he could make a brilliant copy more rapidly than anyone else —certainly in England.

A great deal had been going on in Glasgow, with the rest of the world catching up for twenty years. But at that time, nobody had studied or written anything about it. And the American editor had spent several weeks in a very minute study of the great Scotch town.

Mr. Stead in the Early Days of the London 'Review of Reviews.' The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. | GGA Image ID # 1055d2a425

He would brook no interference from the paper owners. On that account, he gave up the editorship at the beginning of 1890. He had already formed the conception of the Review of Reviews. He brought it out at once as an illustrated monthly, having its own opinions but reviewing the world's more significant discussions and presenting a resume of the more critical steps in making contemporary history.

It was a successful periodical, and Mr. Stead continued to edit it until his death. On the very day of the sinking of the Titanic, his pen was busily engaged, and he was presumably writing an article to be mailed back for the following number of the Review on his arrival in New York.

It was upon Mr. Stead's suggestion and with his help that the American Review of Reviews was founded by its present editor the following year, early in 1891. Although wholly independent of each other in editorship and control and quite different in method and appearance, there has been close and unbroken cooperation between Mr. Stead's English Review and its American namesake.

Many invaluable articles from his pen have appeared from time to time in this magazine, written primarily to inform American readers about English or European personages and affairs.

Mr. Stead had never crossed the Atlantic until, in the autumn of 1893, he accepted an urgent invitation from his American colleague to come as his guest and see the great exposition at Chicago in its closing days.

Mr. Stead, at that time, had been trying to start a daily newspaper in London, which he had been obliged to discontinue through a lack of necessary financial support. This failure was a great disappointment to him, and the moment was one of fatigue and depression, such as he had never experienced before.

Only when this is understood can the circumstances of his visit to Chicago be fully appreciated. His fatigue was so great that he had given a promise not to speak in public during his entire stay.

But he had recently started in England a so-called "civic federation" movement, which had been productive of immediately valuable results in several English cities and towns, where he had succeeded in bringing about a sort of informal union of all kinds of societies and forces that were working for the betterment of the community so that their efforts might be mutually helpful.

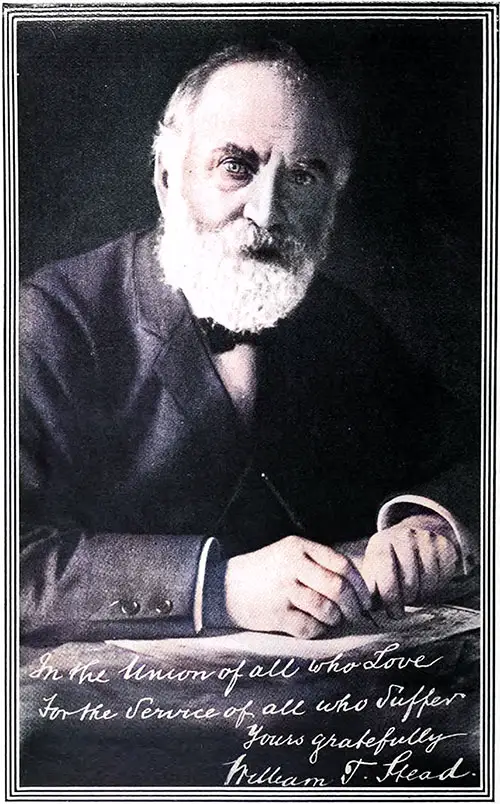

William Thomas Stead, Editor of the English 'Review of Reviews.' Mr. Stead was on board the ill-fated Titanic and was not reported among the rescued. He had suddenly decided to make a brief trip to the United States. He would have addressed the Men and Religion Forward Movement's congress in New York. The American Review of Reviews, May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 105cb136bc

This idea had been taken up in the American Review of Reviews from Mr. Stead's English work, and the result had been the beginnings of similar organizations in several American towns.

The plan had appealed strongly to many people in Chicago who were anxious to have the exposition year followed by a well-considered and permanent program for social and moral progress.

Mr. Stead was recognized as the apostle of such movements. When called upon to expound his views, he could not decline what seemed to him a call of duty and an opportunity for usefulness.

He spoke, not once, but many times. Chicago was, to him, a new and astounding phenomenon. In studying the conditions that needed reform, he was perhaps over-impressed, as a stranger must be, by novelty and contrast.

He did not quite understand the wholesome forces that dominated American life; at any rate, he preferred to give American communities a picture of their worst shortcomings.

If he did not quite understand Chicago, it is true in like manner that Chicago did not quite understand him. He wrote a book called "If Christ Came to Chicago." Many excellent and sensitive Americans felt that this scathing exposure of vice and crime lacked balance and proportion.

Mr. Stead, of course, would not for a moment have denied that an American might have gone at that time to London or Liverpool and found conditions of misery, poverty, brutality, sin, and crime far worse than those existing in Chicago.

Generally speaking, it seems better for the visitor to fight evil in his own country, where he is responsible, than to expose it in another country at the moment of his first landing upon its shores.

But Mr. Stead did the thing that he saw fit to do. He was a genius, a moral enthusiast, and a law unto himself. He had made his exposure of vice in London ten years before, upon his sensational plan, and he had shocked many good people but had accomplished valuable results.

The Chicago visit caused him to be misunderstood in America, and it certainly diminished for several years the influence that his valuable political and social articles might otherwise have gained.

Yet the great National Civic Federation grew out of his suggestions. From the psychological standpoint, and quite apart from moral considerations, the intensity of Mr. Stead's Chicago crusade was due to reaction from the failure of his daily paper, into which he had thrown himself for several weeks with an almost superhuman effort to achieve success by sheer brilliance and personal power.

He had started the paper on faith. He had informed the Lord that if He wished the daily report to be a success, He would have to see that it obtained either a divinely appointed financial backer or else—and preferably—so extensive a public support that it would need no capital.

It was a splendid act of faith and ought to have succeeded. Mr. Stead's attitude toward the Lord in this matter was much like that of Senator Jonathan Bourne's attitude toward the people of Oregon.

A Recent Portrait of William T. Stead ca 1910. The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. | GGA Image ID # 1057a9cecf

Mr. Stead's paper more than swallowed up in a few days the profits of the successful Review of Reviews and failed, although the people of London ought to have had vision enough and generosity enough to have tided it over and made it all that it might readily have become a very significant and brilliant success.

A prophet is sometimes without honor for the moment. Yet, great progressives are also natural optimists, and they recover their faith in the Lord and their fellow men.

Mr. Stead, during the Chicago episode in 1893, felt that he did not want to return to England at all. It took some firm arguing to show him that London must remain the only possible center for his activities and worldwide interests and influence.

He could not have adapted himself in detail to the institutions of any country but his own. However, so ready were his sympathies and so large was his grasp that he could comprehend the principles and the spirit of national life in all countries.

He had begun with a great gospel of the mission of the English-speaking world. He was a tremendous Imperialist. It was his expression of the meaning of England and the influence of Anglo-American ideas that had created in Cecil Rhodes the ambition to paint with British red as much as possible of the map of Africa.

So firmly committed had Mr. Stead been to the ideals of British rule in Africa, as elsewhere in the world, that many of his friends could never understand why, in later years, he opposed so intensely the objects of the Jameson raid and the subsequent war, that resulted in the conquering and absorption of the two little Boer republics.

Mr. Stead would have been delighted with a voluntary federation of the different political entities of South Africa under the aegis of the British flag. But he felt that Mr. Chamberlain, as a colonial minister, had dealt unfairly with the Boers and that the war resulted from a conspiracy in which the business affairs of the Chartered South African Company had been discreditably involved.

His passion for justice was more significant than his zeal for the British Empire. By coincidence, Mr. Chamberlain had sent Alfred Milner, now Lord Milner, to be governor-general and British representative in Cape Colony. Milner had been one of Mr. Stead's editorial assistants in the early days of the Pall Mall Gazette.

His attitude as a pro-Boer cost him many friendships and a considerable part of his popular support. Yet he hammered away with the same brilliance and power he had shown when opposing the Disraeli government and defending the Bulgarians in 1875.

The hostilities of that period are now forgotten, and the men whom he criticized have, in these last weeks, paid tribute to his sincerity and patriotism.

Mr. Stead, with Oliver Crom Well's Pistol and a Statue of General Gordon. The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. | GGA Image ID # 10581902ca

Mr. Stead's last visit to the United States was in 1907, when he participated in the meetings of the Peace Congress. Nobody in these recent years had been more active and zealous than he for the cause of international harmony.

He had written constantly upon various phases of this great question. For a time, he had published a particular periodical, which he called War Against War. He had felt strongly that Italy's attempt to seize Tripoli had been wholly unjustified. He had been the leader in the attempts of the peace societies to secure a reference of the questions at issue to the Hague Tribunal.

His interest in this matter had led to his being invited by the Turkish Government to come to Constantinople and aid in getting the Turkish cause presented for international arbitration. The last interview between Mr. Stead and the present writer was in Paris one day last October. Mr. Stead left that evening by the Oriental Express for the Turkish capital.

His energy and enthusiasm were as great as they had been in the '80s when he was working for the maintenance of the British navy and a good understanding of Russia. His visit to Constantinople was intensely interesting. He was even invited to speak on international peace in the great mosque of San Sophia—an opportunity which his sense of courtesy toward Mohammedan feelings led him to decline.

For a number of years past, he had been an earnest worker for a good understanding between England and Germany, and he had been instrumental in bringing a large body of German editors to visit England. Yet he had always believed that until world conditions were much better than they were, it would be necessary for England to maintain her naval supremacy.

A Garden Party at Cambridge House, Wimbledon. Mr. Stead in Argument with Herbert Burrows and Another Guest. The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. | GGA Image ID # 10585d002b

He was, moreover, a firm believer in the wisdom of maintaining the navy of the United States as an agency of peace and a kind factor in the harmony and progress of the whole Western Hemisphere.

Mr. Stead was always a man of the utmost simplicity in private life. He was generous to everyone who seemed to be in distress, and his kindness was lavished in particular upon those who deserved it so little that nobody else would help them.

As he always reasoned, deserving cases could usually find help and relief, while people in need were the others. He was like an elder brother to his sons and daughters and a delightful companion and loyal friend to those who had come into the circle of his life.

He had always believed in extending to women every legal and political responsibility, as well as every right, granted to men.

His great interest in psychic research and "occultism," so-called, is well known. Many of his friends had deplored his activities as a spiritualist. Doubtless, in certain circles, his influence was diminished by his editing, for some years, a periodical called Borderland and his publishing of what he regarded as communications from the spirit world.

As for those of us who have not given much study to these matters and who are not influenced by the things that brought absolute conviction to Mr. Stead's mind, it is at least permissible to be tolerant and to admit that some of our fellow men may be gifted with natures more sensitive than ours and more perfectly attuned to things not of this world.

Besides his ongoing contributions to the daily press and periodicals, Mr. Stead wrote many books and brochures. While most of these were journalistic in their method, they were of extraordinary influence and power and lucid and brilliant style.

Three of his four sons were trained by him in practical journalism and the business of publishing. The eldest of these, his namesake, died several years ago. The other two, Alfred and Henry, will continue to carry on the Review of Reviews and the business of Stead's Publishing House.

Besides three sons, there survive Mrs. Stead and two daughters.

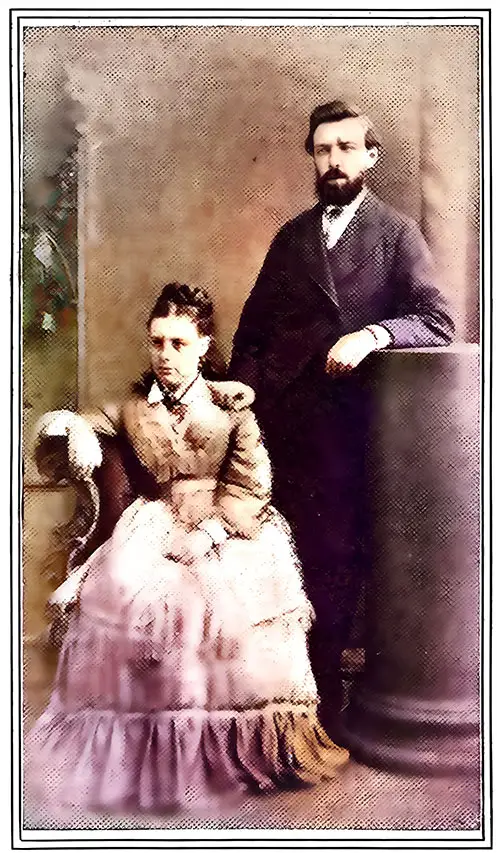

Photograph of Mr. and Mrs. W. T. Stead Taken during Their Honeymoon. The American Review of Reviews, June 1912. | GGA Image ID # 1058751ef9

Henry Forbes Julian - Titanic Victim

Metallurgical Engineer

Henry Forbes Julian, who was lost on the "Titanic," was a well-known metallurgical engineer and a specialist in gold-ore treatment. He was a resident of Torquay, England. He was one of the authors of the valuable work "Cyaniding Gold and Silver Ores."

He was a pioneer in the South African goldfields, where, in 1887, he was one of the consulting engineers to the Johannesburg Pioneer Co. and erected a small plant to treat blanketings from the company's first stamp mill, by the cyanide process.

This was the first cyanide mill in the Transvaal. In 1888, he erected a better plant at the Roodepoort United Main Reef mill. He successfully treated low-grade ores by the cyanide process, then in its infancy.

At about the same time, he was investigating the dissolution of gold ores by chlorine and also by cyanide under high pressure of air and subsequent precipitation by an electric current and sodium amalgam, which resulted in some patent applications in South Africa.

He was on his way to San Francisco to take up some remarkable work in connection with the Butters Patent Vacuum Filter Co., Inc., with which he had been connected for some time.

-- The Engineering and Mining Journal, 27 April 1912, p. 827

Titanic Victim Edgar J. Meyer

Mining Engineer

Edgar J. Meyer was born on Jan. 13. 1884, in San Francisco, and after a preliminary education in that city, he came to New York, where he continued his schooling preparatory to entering Cornell University.

At Cornell, he spent a year in the Academic Department, followed by four years in the School of Engineering, and received the degree of M.E. from that institution in 1905. He was a member of the Zeta Psi fraternity in addition to his regular course.

He was keenly interested in research work and made a particular study of gas engines. The result of his career in this direction brought him specific praise and some of the theories he evolved about the velocity of flame propagation of explosive mixtures were incorporated into the practices prescribed in engineering courses.

After graduating from Cornell with an honorable mention, Mr. Meyer entered the employ of the banking firm of Eugene Meyer. Jr. & Co., of New York, in which firm he subsequently became a partner to his brother, who is the senior member.

This firm has been and still is represented on the boards of one of the largest mining enterprises here and abroad. These interests required Mr. Meyer to spend considerable time in the field. At his death, he was vice president and director of the Braden Copper Co. He was also active as an official of numerous other vital corporations.

In the business and mining world. Mr. Meyer will be remembered as a close and careful student of values. He applied his scientific training with a great degree of sagacity to the consideration of problems of the mining industry and finance in general, and his combined ability as an engineer and businessman was rapidly bringing him to the front.

Nlr. Meyer had incredibly close knowledge of the steel and copper business.

The statistical study and analysis he made in 1909 of the development and operation of the United States Steel Corporation created much favorable comment. His conclusions regarding the position of copper, drawn after a personal investigation in the important copper centers, were accepted as carrying much weight by those most vitally interested in the business. However, at the time of his death, he was but 28 years of age.

Aside from his duties as an active member of a banking firm, he found time to interest himself in various other channels. He has patented several automobile appliances and is also a member of the Technical Committee of the Aero Club.

He met his death in the "Titanic" disaster. In this catastrophe, he distinguished himself in his endeavor to save the lives of others.

According to the accounts of survivors, Mr. Meyer, after seeing his wife safe into one of the boats, remained and helped lower the last lifeboat of women and children that left the ship. Mr. Meyer was married in 1910 to Miss Leila Saks, daughter of the late Andrew Saks, who, with a little girl of one year, survives him.

Titanic Victim Ernst A. Sjostedt

Metallurgist

Ernst A. Sjostedt, one of the victims of the "Titanic" disaster, was the Lake Superior Corporation chief Metallurgist of Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., was returning from a three-month European visit in connection with the company's business.

Mr. Sjostedt was born in Sweden in 1852 and graduated from the Stockholm School of Mines. He came to America in 1876, was engaged at the Bethlehem Steel Works, and afterward became manager of several iron plants in the United States.

For some years, he was in business in Montreal as a consulting metallurgist, and in 1898 went to Sault Ste. Marie was an associate of F. H. Clergue in establishing the group of enterprises subsequently taken over by the Lake Superior Corporation, one of the most important of which was the manufacture of ferronickel steel.

He built the reduction works and the water-gas plant at the Sault. He was recognized as one of the leading metallurgical authorities in Canada. He leaves a widow and one daughter.

Titanic Victim George D. Wick

Iron & Steel Company Executive

George D. Wick, of Youngstown, Ohio, was one of the passengers lost in the wreck of the “Titanic.” He had been connected with the iron interests of the Mahoning Valley all his active life, succeeding his father, who was a well-known ironmaster. Col. Wick was vice-president of the Union Iron & Steel Co., Youngstown, when it was sold to the National Steel Co., now part of the Carnegie Steel Co.’s works.

He then became vice-president of the Republic Iron & Steel Co., with offices in Chicago, but after one year with James A. Campbell, he founded the Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co., at Youngstown. Because of ill health, Mr. Wick retired from the presidency of that company.

Later he purchased control of the Carry Iron & Steel Co., at Cleveland, and about a year ago merged it with the Empire Iron & Steel Co., of Niles, Ohio. On the formation recently of the Brier Hill Steel Co., he sold out his interests in the Empire company.

The Late Samuel Ward Stanton in His Studio. He was a victim of the RMS Titanic disaster. The Nautical Gazette, 11 September 1912. | GGA Image ID # 10af513425

Ever since the unfortunate loss of Samuel Ward Stanton among the passengers of the "Titanic," the NAUTICAL GAZETTE has endeavored to obtain a photograph of the man which would do him justice and be appreciated by his many friends, but there appear to have been none.

He was a man who preferred to be known by his works, and the best available picture of him is a snap-shot, which Mrs. Stanton found and kindly loaned to this paper for reproduction. It shows him at work and was taken in his studio in The Alpine, 33rd Street and Broadway, on 27 June 1908.

Mr. Stanton was, at that time, as he had been for many years, editor of the NAUTICAL GAZETTE, but his beloved art occupied all his leisure time, and how well he improved it is shown by the many of the toric paintings he has left behind and the fame which they secured for him.

He was, as is well known, returning from a trip to Europe to obtain material for the paintings for the new steamer for the Hudson River Day Line, the "Washington Irving," now being completed, when his most promising career was so suddenly cut off and a wife and three children, as well as a numerous circle of friends, left to mourn.

The Service for the RMS Titanic Victims - April 1912

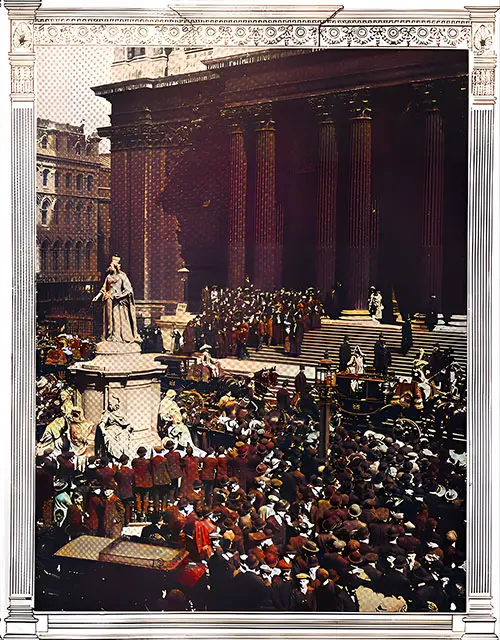

The Crowd Outside St. Paul's after the Titanic Memorial Service on 19 April 1912. The Illustrated London News, 11 May 1912. Photo by L.N.A. | GGA Image ID # 101f0406c4.

In the Hours of Strongest Feeling: The "Titanic" Service. Gathered to Show Sympathy with the Sorrow of Two Peoples: The Crowd outside St. Paul's after the Memorial Service on April 19, 1912.

The unique memorial service at St. Paul's on April 19 gave proof of the truth of Archbishop Tait's words: "Always in their hours of strongest feeling, men acknowledge that they need a church."

In the choir sat the Lord Mayor, some members of the Cabinet, including Mr. Sydney Buxton, President of the Board of Trade, The United States Ambassador, and other diplomatists and representatives of the White Star Line.

No seats had been reserved in the body of the cathedral, and rich and poor sat together in the vast congregation, united in a common sorrow.

The altar, stripped of all ornament but the Cross and two tall candlesticks, was draped in black and white, and a black carpet covered the steps. The band, one hundred strong, from Kneller Hall, were seated in front of the choir.

The service was simple but most moving and impressive, especially the rendering of the Dead March in "Saul."

Among the hymns were "Rock of Ages" and "Eternal Father, strong to save"—the well-known hymn "for those in peril on the sea."

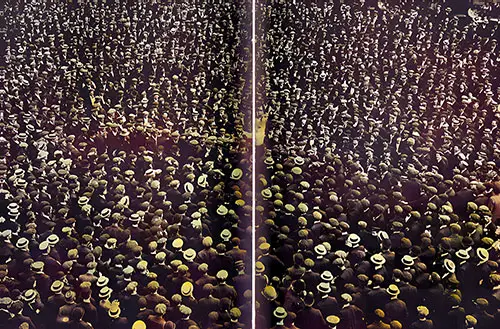

A Crowd Equal to That Which Was Lost with the Ill-Fated White Star Liner Titanic. The Illustrated London News (11 May 1912) p. 704-705. © Topical. | GGA Image ID # 101fc2d5d0.

Crowd Equal to That Which Was Lost with the Ill-Fated White Star Liner: Sixteen Hundred and Thirty-Five People. The Number Reported Drowned in One of the Greatest Maritime Disasters.

By the sinking of the liner "Titanic" after collision with an iceberg, sixteen hundred and thirty-five people were drowned. There were 705 survivors: 202 first-class passengers, 115 second-class, 178 third-class, 206 of the crew, and four officers.

Such figures, informative as they are, do not convey at once the extent of the catastrophe: they transmit little more than a blurred impression of a considerable number to the mind.

This photograph represents a crowd totaling precisely 1635, a crowd equal, that is to say, to the roll of those who perished. It was taken on Tower Hill when Mr. Ben Tillett was speaking recently.

It was Mr. Tillett whose signature appeared on an extraordinary document drawn up after the disaster by the executive of the Dock, Wharf, and General Workers' Union, which is reported as saying: "We offer our most vigorous protest against the wanton and callous disregard of human life and the vicious class antagonism shown in the practical forbidding of the saving of the lives of the third-class passengers.

The refusal to permit other than first-class passengers to be saved by the boats is a disgrace to our common civilization."

It need not be said that there is truth in the allegations thus made, and it is good to know that several Labor leaders have repudiated the document.

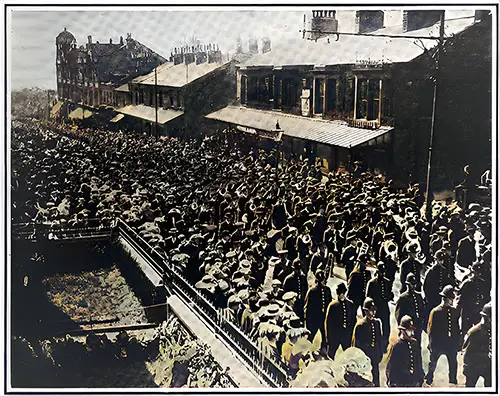

Funeral Procession of Mr. Wallace Hartley of the RMS Titanic in Colne, Lancashire. The Illustrated London News, 8 June 1912. © Farringdon Photo Co. | GGA Image ID # 101fe60747.

The Burial of the Heroic Bandmaster of the "Titanic": The Funeral Procession of Mr. Wallace Hartley, at Colne, Lancashire.

The remains of Mr. Wallace Hartley, the bandmaster of the liner "Titanic," who, accompanied by his musicians, continued playing as the great vessel sank, were laid to rest on May 18 in his native town, Colne, Lancashire.

Some 30,000 people were present, and figuring in the funeral procession were the Corporation of Coyne, representatives of various institutions with which Mr. Hartley was associated, members of the East Lancashire Territorial Regiment, five brass bands, and many of the Lancashire County Constabulary, mounted and on foot. It will be remembered that when Mr. Hartley's body was recovered from the sea, his music case was strapped to it.

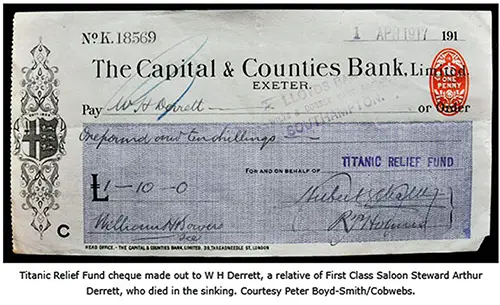

Titanic Fund Distribution - 1912

Two Widows and Their Children. Steerage Survivors Who Will Find the Relief Fund a Godsend. Photo by Underwood & Underwood. The Literary Digest, 4 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 10867a42f9

Two Widows and Their Children. Steerage Survivors Who Will Find the Relief Fund a Godsend. Photo by Underwood & Underwood. The Literary Digest, 4 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 108It is one of the bright spots in our memory, the work we did for the unfortunate Titanic seamen. Our help was temporary to the survivors, and the friends who so generously helped them will be pleased to learn something about the permanent aid to the widows, children, and dependents of those who perished in the most significant marine catastrophe the world has known.