Anatomy of the RMS Titanic Disaster

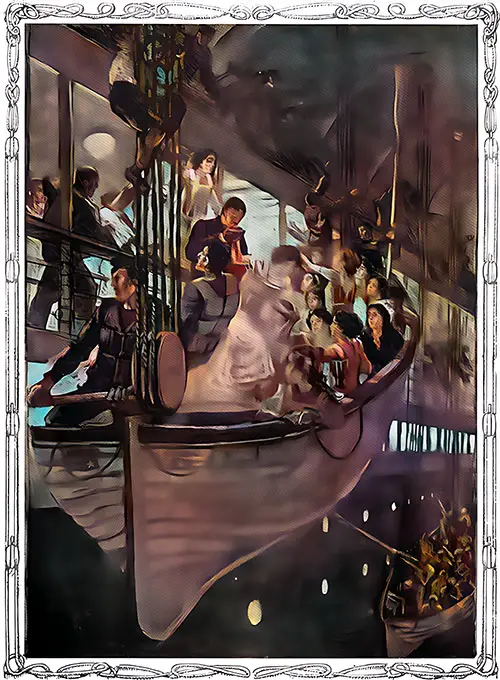

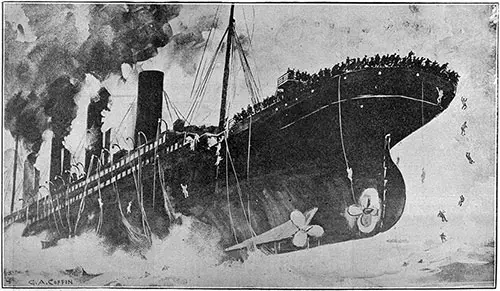

The Sinking of the Titanic. As the Mortally Wounded Liner Neared the Last Moments of Her Death-Struggle, the Inrush of Water to Her Forward Compartments Depressed Her Bow, Leaving Her Stern Clear of the Water. Our Artist Depicts Her as She Appeared to the Horrified Survivors in the Lifeboats Just before She Took Her Final Plunge. 1,635 Persons Went to Their Death with Her (According to the Official Estimate of the White Star Management) or Perished Afterward from Exposure and Shock, 705 Persons Survived the Disaster, According to the Most Trustworthy Figures Available as the "Weekly" Goes to Press. Drawn from Descriptions of Eyewitnesses by L. A. Shafer. Harper's Weekly (27 April 1912) p. 34-35. | GGA Image ID # 109dc2a899

Explore the events, ships, and personalities that made this particular disaster the most written about the marine disaster of all time. From being touted as "Unsinkable" to its chilling dive to the bottom five days into its maiden voyage. After reading these incredible and sometimes incredulous stories, one might wonder if this was a vortex of the Bermuda Triangle.

Timeline of the RMS Titanic Disaster - 1912

New York American Latest News on the White Star Liner "Titanic." Photograph Showing Crowd of People Surrounding the Building on 15 April 1912. | GGA Image ID # 1628bc838f

April 10.—The new White Star liner Titanic, the largest vessel ever constructed, sails on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York.

April 15.-The steamer Titanic, 1,150 miles east of New York, founders four hours after striking an iceberg, carrying 1,595 persons down with her; 745 of the passengers and crew, all that the lifeboats would hold, are afterward picked up by the Carpathia, which had been summoned by wireless.

April 15.—The White Star liner Titanic, on her maiden voyage to New York, is sunk by an iceberg 400 miles southeast of Cape Race. Of the 2,181 on board, 705 were rescued by the Cunard liner Carpathia, and 1,476 were lost, according to the estimate of the Carpathia's officers.

April 16.—The cable steamer Mackay-Bennet, chartered by the White Star Line to search for bodies at the disaster scene, left Halifax, NS. The Canadian Government steamer Minia dispatched on a similar errand, returned on 6 May with 15 bodies, among them that of Mr. Hays, having buried two at sea.

April 17–The Senate orders an investigation into the causes that led to the wreck of the Titanic. Mayor Gaynor of New York starts a relief fund for sufferers from the sinking of the Titanic.

April 17.—The Senate passes a resolution calling for an official investigation of the cause of the sinking of the Titanic. Mayor Gaynor of New York starts a relief fund for sufferers from the sinking of the Titanic.

April 18.—RMS Carpathia arrives in New York with 495 passengers and 210 crew members of the wrecked Titanic.

April 18.—The liner Carpathia arrives in New York with the passengers and members of the crew picked up after the sinking of the Titanic.

April 19.—The Senate passed the Dillingham Immigration Bill, allowing people to read and write a condition of entrance into this country. The House adjourns concerning those who lost their lives on the Titanic. A Congressional inquiry into the causes leading to the wreck of the Titanic is begun by Senators Smith and Newlands in New York. A memorial service for those who lost their lives on the Titanic is held in St. Paul's Cathedral.

April 20.—It is announced that hereafter, steamers of the International Mercantile Marine will carry lifeboats and rafts sufficient for all passengers and crew.

April 21.— Memorial services for the Titanic dead are held in many churches throughout the British Empire and the United States. Abraham ("Bram") Stoker, the English author and theatrical manager, dies at age 54.

April 24.—The steamer Olympic cannot sail from Southampton because of the objection of firefighters and oilers to its lifeboat equipment.

April 30.—The cable ship Mackay-Bennett brings to Halifax 190 bodies picked up from the sea near the place where the Titanic foundered.

May 2.—The British commission under Lord Mersey begins its investigation of the causes leading to the wreck of the Titanic.

May 2.—The British inquiry into the Titanic disaster has begun.

May 3.—Fifty-nine unidentified bodies of Titanic victims recovered by the Mackay-Bennett are buried at Halifax.

May 6.—The will of John Jacob Astor, made public in New York, leaves the bulk of his estate of more than $100,000,000 to his twenty-year-old son, William Vincent Astor. The cable ship Minia arrives at Halifax with the bodies of fifteen Titanic victims.

May 28—The Senate committee investigating the sinking of the Titanic reported its findings. It made many recommendations for safeguarding life at sea. In a joint resolution, Congress thanks the officers and crew of the liner Carpathia for rescuing Titanic survivors.

July 10—President Taft signed the joint resolution extending the thanks of Congress to Captain Arthur Henry Rostrum of the Carpathia and appropriating 1,000 for a gold medal to be presented to him for his action in rescuing the Titanic passengers.

July 30—Lord Mersey delivered the judgment of the British Board of Trade Court of Inquiry into the disaster of the White Star Line steamship Titanic, which sank with a loss of 1,517 lives after collision with an iceberg on 15 April.

Sixteen Hundred Lives Lost on the “Titanic”

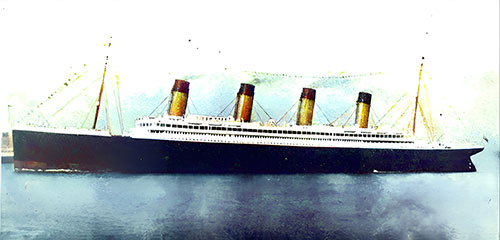

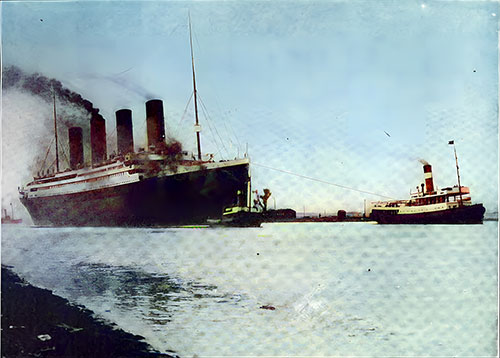

The Ill-Fated Steamship “Titanic " (Vessel With Four Funnels) Leaving Southampton, England, on Her Maiden Voyage, Which Ended With Disaster off Newfoundland. Some Idea of the Magnitude of This Leviathan of the Ocean May Be Gained From the Fact That as She Was Drawing Away From Her Dock at Southampton, and Before She Had Attained Anything Like Her Maximum Speed, Which Was Twenty-Six or More Miles an Hour, the Tremendous Suction Caused by Her Great Displacement and Momentum Dragged the Steamship " New York ” (Vessel With Two Funnels ) From Her Moorings, Tearing Her Enormous Hawsers Apart as Though They Were Mere Threads. A Serious Collision Was Narrowly Averted by the Tugs in Attendance Upon the Larger Vessel. | GGA Image ID # 17049466cc

The full measure of the horrors that marked the sinking of the Titanic, as well as stories of heroism that are not surpassed in the world's records of the fearless acts of men in dire emergency, was made known on arrival in New York, on April 18th, of the ship of rescue, the Carpathia.

The Titanic Rescue Ship, RMS Carpathia of the Cunard Line. Leslie's Weekly 2 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 1705c510c8

The Cunard liner RMS Carpathia bore 705 persons—a majority of them women and children—saved from the lifeboats of the Titanic found drifting in the ice floes after the great steamship, mortally stricken, had disappeared in the deep.

The rescuers found that many of the women and children in the boats were unconscious from the combined agony of their experiences and the freezing atmosphere.

Among those told to man the boatsFour members of the Titanic's crew were dragged to the decks of the Carpathia lifeless. They had been frozen to death, and their hands were stiffened about the oars.

No imagination can picture the mental suffering of these survivors of the calamity. Wives had parted from husbands and children from fathers, initially believing in the ultimate safety of the dear ones left behind.

But even while the lifeboats, cruising about aimlessly for a time, were within sight of the doomed vessel, she sank with more than sixteen hundred unfortunates to the bottom of the sea.

Illustration of the RMS Titanic Striking an Iceberg in the North Atlantic on 15 April 1912. Leslie's Weekly, 2 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 1706936f01

From stories told by the survivors, it was learned that the Titanic was running in a fair sea when she was crushed into a submerged iceberg. The shock was not generally alarming.

It was near midnight, and a majority were in their cabins. The band was still playing, for many had not retired. The ship's crew ran about to alleviate any fear that might be felt—some passengers who had emerged to the decks returned to their quarters. The engines slowed up, and assurances of safety were repeated.

Suddenly, the great ship began to list. There were cries of authority from officers. Passengers were ordered to the decks with life belts. Then confusion began, for the masses of men and women realized that danger was imminent. The alarm that spread was increased in those who saw the sailors working with expert speed at the lifeboats.

All at once came the order, "Women and children to the boats!" As the boats were filled and lowered—the sailors helping those nearest to this means of safety —excitement grew. Yet some men stood unconcerned, jesting, seemingly assured that the great ship could never go down.

The Titanic continued to list to port, and fear and excitement soon became general. Women and children were rushed to the lifeboats, which were lowered as quickly as possible.

At the same time, officers and crew thrust aside men who lost their reason in the confusion that ensued. Other men revealed the noblest heroism. Husbands forced their wives into the boats, and some of them, at the same time, fought off men who tried to save themselves at the expense of the weak. The scenes grew more terrible as the moments passed.

Only sixteen lifeboats were floated with their precious freight. The last to be launched, a collapsible boat, overturned but was used as a raft, upon which many men and women were finally saved.

While many women were rescued, many were engulfed by the ship. These were of the poorer class in the steerage, unable to reach the upper decks, many in the cabins who refused to leave their husbands, and servants of families left in the frantic haste of the last few moments of the preliminaries of rescue.

Some of these, with many of the unfortunate men who had remained below with a feeling of security which nothing but the listing of the ship could dissipate, were seen frantic upon the decks just before the climax of the catastrophe.

As stories of individual heroism were told, the rescue of a comparatively large number of men was only understood once it was learned that, while the earlier lifeboats were being launched, few women had appeared to fill them, and men present were forced into them.

When it became apparent to all who remained that the Titanic was doomed, frenzy and riot marked the lowering of the latest boats. This was primarily due to an accession of stokers and men from the steerage, who fought their way to the upper decks and engaged with cabin passengers in a struggle for precedence.

As noble a body of men as ever crossed the sea, the ship's officers stood by. They continued to enforce the law on women and children by exercising the only type of force that could be effective. They calmly shot down the foremost who sought to leap into boats already loaded to the limit.

First Officer Murdock, who was on the bridge when the Titanic struck, shot himself when he realized the ship was doomed. Captain Smith leaped Into the sea and fought off a cook of the vessel, who sought to drag him into a boat, sinking before the Titanic finally went down.

Colonel John Jacob Astor died a hero's death, standing calmly on the deck and awaiting his fate after seeing his young wife to safety in a boat. The ship's barber, Alfred Whitman, who jumped from the ship and was taken aboard a lifeboat, was the last to speak with Astor, whom he sought to leap overboard. "No, thank you," was the reply. "I think I'll have to stick."

Isidor Straus and Mrs. Straus only appeared on deck when a second alarming order had been given below. Mrs. Straus refused to enter a boat, preferring to risk her life with her husband, and they were seen calmly awaiting their fate together.

Major Butt, President Taft's aid, was said to have been seen at a critical moment with an iron bar in his hands, repelling the attempts of stokers and steerage men to enter a boat to the danger of women.

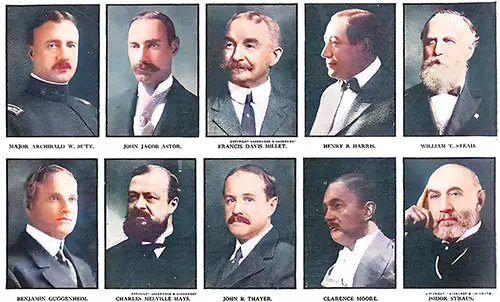

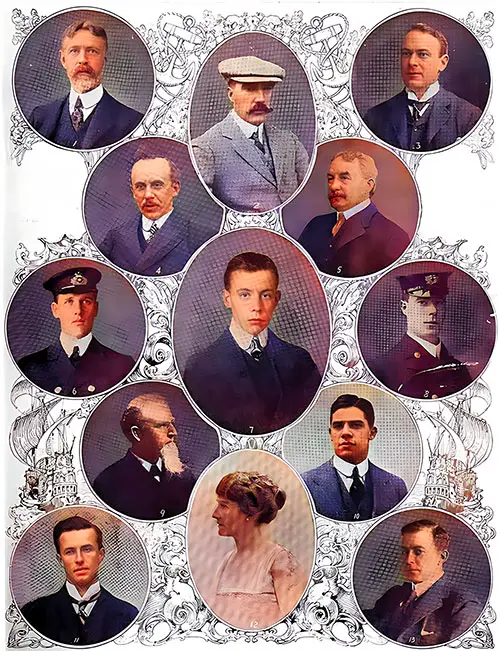

Distinguished Dead Among the “Titanic’s ” Heroes. Leslie's Weekly 2 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 1705104474

The Titanic's passenger list included many persons of great distinction and prominence, an appalling number among the lost. Included with the hundreds of the dead are Colonel John Jacob Astor, one of the wealthiest of Americans; Jacques Futrelle, famous American novelist; Charles M. Hays, president of the Grand Trunk Railway Company; Henry R. Harris, one of the most prominent of American theatrical managers; Major Archibald Butt, military aid to President Taft; William T. Stead, the famous English journalist and reformer; Benjamin Guggenheim, of the noted family of capitalists; F. D. Millet, a celebrated artist; Isidor Straus, the merchant and philanthropist of New York, and his wife; John B. Thayer, vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad; Colonel Washington Roebling, of the family of distinguished engineers; G. D. Widener, of the prominent Philadelphia family, and his young son; Washington Dodge, Clarence Moore, H. S. Harper, Dr. Henry W. Frauenthal, J. G. Reuchlin, managing director of the Holland-American Steamship Line, and others.

It is known now that, out of 390 first-cabin passengers, 202 were saved, 164 of whom were women and children. In the second cabin, 116 out of 270 were saved, 102 women and children.

Only 178 out of the 800 steerage passengers survive, of whom 83 are women and children. Of 985 officers and crew, 210, of whom 22 are stewardesses and maids, are now alive. The total number on board the Titanic was 2,181, of whom 1,635 were dead.

The passengers who were interviewed just after the Carpathia had landed her sad and pitifully small complement of survivors agreed that, almost without exception, the men of the Titanic, passengers, and sailors, had effaced selfishness that the women and children might live.

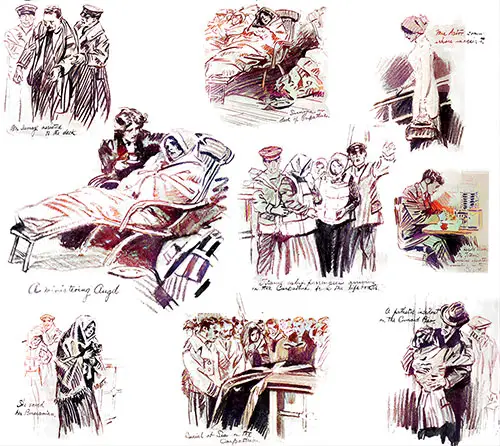

Drawings of the RMS Titanic Aftermath. Leslie's Weekly 2 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 170652f9c5

At first, the putting of the women and children into the small boats was considered by many as a joke. Husbands kissed their wives goodbye with an "I'll see you in half an hour," "You'll have to come back here soon." and "I think I'd rather stick to the ship.''

Only the ship's officers and crew and some of the intuitively keen among the women knew at first the real menace and how hard hit the Titanic must be for the passengers to be ordered to the small boats.

That so many men from among the passengers were saved, except for one or two to whom, as has been well established, self-consideration was paramount, is due to the different instructions of the officers in charge of the port and starboard boat loading.

Only the women, children, and sailors enough to operate the boats were allowed overboard on the port side. On the starboard side, all the husbands who came up to the ships with their wives were permitted and encouraged to enter them.

Almost without exception, however, the men of the Titanic were men. As they came to realize, with the gradual settling of the ship and an ever-increasing list to port, that they were indeed doomed, they stopped their pacing of the deck. They gathered in little knots along the rail, looking out over the ice-dotted ocean at the cockleshell boats in which their loved ones were moving to safety.

Gradually, the Titanic sank deeper and deeper, one deck after another submerged, those left aboard mounting ever upward as the water crept upon them.

About two hours after the Titanic had rammed the iceberg, the ship's band appeared with its instruments on the wave-lapped boat deck. Erect, with bared heads, they played "Nearer, My God, to Thee." The passengers aboard the ship took up the hymn.

Those in the small boats, helpless themselves, heard the song. From apparently the same emotion, everyone in the lifeboats refrained from singing.

At the same time, they listened, unable to aid the "Morituri, te salutamus" of their loved ones still aboard the stricken liner. With the eyes of many in the boats fixed upon her in anguish and terror, the Titanic plunged to her ocean bed, 12,000 feet below.

Three of the survivors died on the Carpathia on the way to New York. Many on arrival were seriously ill, and several had continued in a hysterical condition for days. Among the survivors picked up were several babies, thrown overboard from the Slavic by their frantic parents and picked up by the boats. Their identity may never be known.

Among the survivors were thirty women whom the disaster had widowed. The men rescued all had their wives with them. The scenes as the Carpathia landed with the survivors wrung the hearts even of spectators drawn to the pier by curiosity.

J. Bruce Ismay, chairman of the board of directors of the International Mercantile Marine and managing director of the White Star line, was among the saved. Upon arrival In New York, he was summoned to testify before a congressional committee investigating the disaster.

All stories told of the catastrophe dwell upon the incredible bravery of the noted men who lost their lives.

After his wife had been placed in a lifeboat, Colonel Astor was busy assisting women to safety. He put a woman's hat, lying on the deck, on a boy's head to disguise him as a girl so that he might be taken aboard.

Major Butt was, in effect, made an officer of the doomed ship by Captain Smith after she struck and steadily rendered valuable aid in preserving order and aiding women to escape.

The story of the Spartan-like conduct of Isidor Straus and his wife is reiterated again and again. Benjamin Guggenheim, with his secretary, an Armenian named Giglio, were active on deck and bravely met their fate.

One report was that, just before the ship plunged to the bottom, Colonel Astor and William T. Stead leaped into the sea and caught on to wreckage but were finally so numbed by the cold that they relaxed their hold and sank.

The material losses caused by the disaster have been estimated at $16,000,000, of which $8,000,000 represents the cost of the Titanic. The Post-office Department reports the loss of 3,460 bags of mail matter.

Again—and more strikingly than ever —the priceless value of wireless telegraphy in marine emergencies has been demonstrated. That alone was due to saving the 706 persons whom the Carpathia picked up.

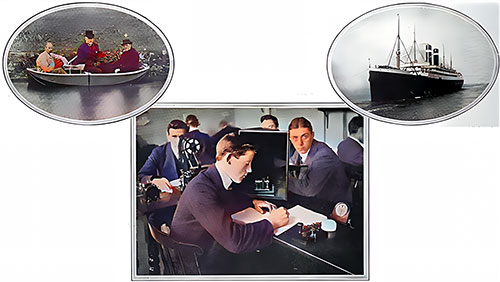

Howard Thomas Cottam, the wireless operator on the Carpathia, had finished his work on that vessel for the night but returned to his instrument before retiring from curiosity as to general news that might be in the air and caught the call of the Titanic's operator for help.

The Carpathia at once sped on her way to the stricken ship. Phillips, the head wireless operator on the Titanic, went to his death on duty. Harold Bride, a subordinate operator on the ill-fated ship, was rescued. Upon arrival in New York, he was removed to St. Vincent's Hospital.

The Mackay-Bennett, a cable steamer sent from Halifax to search for bodies, carried ministers, undertakers, embalmers, and coffins. She recovered sixty-four identifiable bodies. Other bodies past identification were buried at sea. The bodies were recovered about sixty miles from the spot where the Titanic disappeared.

Fourth Officer Boxhall of the Titanic stated that shortly before the Titanic sank, he saw the red side lights of a ship five miles away coming toward the liner. He signaled with rockets and by Morse to the vessels, which veered off without answering.

Six of the lifeboats, with a combined capacity of 390 persons, put off from the Titanic with but 192 persons in them, and many more might have been saved had the ship's crew shown adequate training. The crew were picked men, but it is apparent that they had yet to be drilled in emergency duties.

The disaster demonstrated that the ship carried too few boats for the safety of its passengers. However, it had the usual complement of ocean liners of the day.

In response to public demand, ship companies are increasing their lifeboat capacity. Moreover, the more prominent transatlantic companies have agreed to change the ship lanes to more southern courses during this year's season, making the ocean trip from 160 to 200 miles longer.

Loss of the White Star Liner "Titanic" - 1913

The last photograph of the Titanic taken as she was leaving Southampton on her Maiden Voyage. The Unsinkable Titanic (1912) p,. 117. | GGA Image ID # 100a8db716

Loss of the White Star Liner “Titanic”

Date: April 15, 1912.

Place: Atlantic Ocean, lat. 41:16 North, long. 50:14 West.

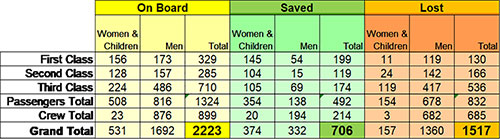

The following table, showing the number of persons on board the Titanic, the number saved, and the number lost, is from the Senate committee's official report:

Table of RMS Titanic Passengers and Crew, Saved or Lost. © GG Archives 2019. | GGA Image ID # 105dd9c0c4

- Persons Aboard: 2,223

- Lives Lost: 1,517

- Persons Saved: 706

- Cause of Disaster: Collision with Iceberg.

The White Star liner Titanic, the newest, finest, and largest steamship, collided with an iceberg at 11:46 p.m. Sunday, April 14, 1912, and sank at 2:20 a.m. Monday, April 15, causing the loss of 1,517 lives.

Seven hundred and six persons, mostly women and children, were saved using lifeboats and rafts. These survivors were picked up by the steamship Carpathia, which, in response to a call by wireless for assistance, arrived at the scene of the disaster at 4 a.m. and conveyed them to New York, that port being reached on the evening of Thursday, April 18.

The Titanic was making its first voyage across the Atlantic, having left the hands of its builders in Belfast on April 2. It sailed from Southampton on April 10, and, after calling at Cherbourg, France, the same day, and Queenstown, Ireland, the following day, it proceeded toward New York, taking the usual southerly spring course.

Notable Passengers and Crew

There were many passengers aboard, many of them attracted by a desire to witness the performance of the gigantic vessel on its initial trip and share in its comforts and luxuries.

Among Them Were:

- J. Bruce Ismay, chairman and managing director of the White Star line and president of the International Mercantile Marine company;

- William T. Stead, the widely known London editor;

- John Jacob Astor, the New York capitalist;

- Charles M. Hays, president of the Grand Trunk Railroad company;

- Frank D. Millet, artist;

- Lord and Lady Duff-Gordon of England;

- Maj. Archibald Butt, military aid to President Taft;

- J. B. Thayer, second vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company;

- Washington A. Roebling, bridge engineer, Trenton, N. J.;

- Isidor Straus and Benjamin Guggenheim, New York capitalists;

- George D. Widener, son of P. A. B. Widener of Philadelphia;

- Jacques Futrelle, author, and Henry B. Harris, theatrical manager, were also among the persons of note in the passenger list.

- Capt. E. J. Smith was in command of the ship.

The voyage at the start was uneventful. The sea was calm, and the weather clear, though rather cold. The wind was westerly to southwesterly. As usual, with new ships, the speed gradually increased daily.

According to a statement by Mr. Ismay, the distance covered on the first day was 464 miles, on the second, 519 miles, and on the third, about 546 miles. No attempt, he said, was made to reach the full speed of which the vessel was capable, as it was not intended to reach New York until Wednesday morning.

Ice Warnings Received

Sunday, the wireless operators aboard the Titanic received three warnings that icebergs were in or near the vessel's course. The first came from the Baltic at noon, the second from the Californian of the Leyland line about 7 p.m., and the third about an hour before the collision.

Sixty-Nine Miles Long and from Three to Twelve Miles Wide: The Great Ice-Floe Encountered by the Ill-Fated Titanic. The Illustrated London News (18 May 1912) p. 741. | GGA Image ID # 100a4107e8

This was also from the Californian, the message reading: "We are stopped and surrounded by ice." To this last message, the operator on the Titanic is reported to have replied: "Shut up. I am busy. I am working Cape Race."

The Baltic's operator overheard ice reports going to the Titanic from the Prinz Friedrich Wilhelm and the Amerika. In contrast, the Carpathia, on the same day, overheard the Parisian talking with other ships about ice.

No special attention was paid to these warnings by the officers of the Titanic, except that one of them instructed the lookouts to keep "a sharp lookout for ice."

Capt. Smith remarked to Second Officer Charles S. Lightoller, who was on duty on the bridge until 10 p.m. Sunday, "If it is in the slightest degree hazy, we shall have to go very slowly. If in the least degree doubtful, let me know." There was no haze, and the ship's speed of 21 knots, or 24 1/4 miles an hour, was not reduced.

Collision with Iceberg

At 11:46 p.m., the lookout signaled the bridge and telephoned the watch officer, "Iceberg right ahead." The officer of the watch, First Officer W. M. Murdoch, immediately ordered the quartermaster at the wheel to put the helm "hard a-starboard" and reversed the engines, but while the sixth officer, J. P. Moody, standing behind the quartermaster at the wheel, reported to Officer Murdoch "The helm is hard a-starboard," the Titanic struck the ice.

The Titanic Struck a Glancing Blow against an Underwater Shelf of the Iceberg, Opening Up Five Compartments. Had She Been Provided with a Watertight Deck at or near the Water Line, the Water That Entered the Ship Would Have Been Confined below That Deck. The Buoyancy of That Portion of the Boat above Water Would Have Kept Her Afloat. As It Was, the Water Rose through Openings in the Decks and Destroyed the Reserve Buoyancy. The Unsinkable Titanic (1912) p. 125. | GGA Image ID # 100a665876

The impact, while not violent enough to disturb the passengers or crew or to arrest the ship's progress, rolled the vessel slightly and tore the steel plating above the turn of the bilge. A few passengers came on deck to find out what the trouble was, but there was no alarm.

Immediately after the collision, the air was heard whistling or hissing from the overflow pipe to the forepeak tank, indicating the escape of air from that tank because of the inrush of water.

Practically at once, the first three compartments in the hold and the forward boiler room, as well as the forepeak tank, filled with water, and reports of the situation were made from the mail and trunk room in No. 3 hold and the firemen's quarters in No. 1 hold.

Leading Fireman Barrett saw the water rushing into the forward fireroom from a tear about two feet above the stokehold floor plates and about twenty feet below the waterline, the tear extending two feet into the coal bunker at the forward end of the second fireroom.

The reports Capt. Smith received it after various inspections of the ship and must have acquainted him promptly with its serious condition. When interrogated by Mr. Ismay, he so expressed himself.

It is believed also that this severe condition was promptly realized by the chief engineer, J. Bell, and by the builders' representative, Thomas Andrews, both of whom perished.

Under the added weight of water, the bow of the ship sank deeper and deeper, and through the open hatch leading from the mail room and through other openings, the water overflowed E deck, below which the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth transverse bulkheads ended, and thus flooded the compartments abaft No. 3 hold.

The Titanic was fitted with fifteen transverse watertight bulkheads. Still, only one extended to the uppermost continuous deck, C. The others rose only to decks D and E.

The bulkheads, having openings through deck E, were not watertight, as it was subsequently shown that the flooding of that deck contributed largely to the ship's sinking.

Theoretically, two of the sixteen main watertight compartments might be flooded without involving the ship's safety. As already stated, the five extreme forward compartments were flooded almost at once because of the nonwatertight character of the deck at which the transverse bulkheads ended, and the vessel's sinking was inevitable.

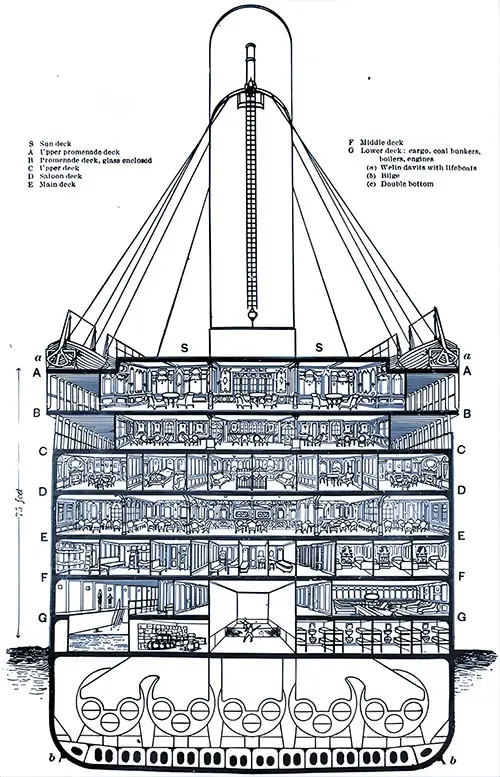

Transverse (Amidship) Section of the Titanic. Loss of the Steamship Titanic (1912) p. 89. | GGA Image ID # 100b7d712b

- S: Sundeck

- A: Upper Promenade Deck

- C: Upper Deck

- D: Saloon Deck

- E: Main Deck

- F: Middle Deck

- G: Lower Deck (cargo, coal, bunkers, boilers, engines)

- a): Welin Davits with lifeboats

- b): Bilge

- c): Double bottom

Call for Help

No general alarm was sounded, no whistle blown, and no systematic warning was given to the passengers. Within fifteen or twenty minutes, Capt. Smith visited the wireless room and instructed the operators, J. G. Phillips, and Harold S. Bride, to call for assistance by sending out the distress signal, "C. Q. D." At the time the call was sent out, there were eight vessels within reach of the Titanic's wireless apparatus.

These were the Californian, westbound, 19.5 miles (or less) to the north; the Mount Temple of the Canadian Pacific line, westbound, 49 miles to the west; the Carpathia of the Cunard line, eastbound, to the southeast; the Birma, a Russian ship, 70 miles distant; the Frankfurt of the North German Lloyd line, eastbound, 153 miles to the southeast; the Virginian of the Allan line, about 170 miles distant; the Baltic of the White Star line, eastbound, 343 miles to the southeast, and the Olympic, sister ship of the Titanic, eastbound, 512 miles to the westward. The Caronia, some 800 miles to the eastward, also overheard the Titanic's call for aid.

The distress call was heard by the wireless station at Cape Race, together with the report that the vessel had struck an iceberg. From this station, the news of the accident, which at first was not thought to have involved the loss of life, was given to the world.

The C. Q. D. signal was also heard by the Mount Temple, the Frankfurt, the Baltic, the Carpathia, and the Virginian. They relaid it to other vessels. At an investigation undertaken by a committee of the United States Senate, from whose official report this account of the disaster is largely taken, sixteen witnesses from the Titanic, including officers, seamen, and passengers, testified to seeing the lights of a vessel in the distance, just after the collision.

The Titanic fired distress rockets and attempted to signal by electric lamp and Morse code to this vessel. At about the same time, the officers of the Californian saw rockets in the general direction of the Titanic, and, according to the testimony subsequently given by them, they displayed a powerful Morse lamp.

Several of the crew of the Californian testified before the senate committee that the side lights of a large vessel going at full speed were visible from the lower deck of their ship at 11:30 p.m. or just before the accident.

The wireless operator on the Californian was not aroused until the early morning of the 15th when he was directed to find out what the rockets, seen hours before, meant. It was then learned that the Titanic had sunk, but it was too late to give any assistance.

In its report, the Senate committee expressed the opinion that the Californian was much nearer the Titanic than the nineteen miles reported by the captain and that it might have had the distinction of saving the lives of the passengers and crew of the sinking liner.

The Frankfurt replied to the distress call but failed to give its position, and when it later asked the Titanic, "What is the matter?" one of the operators on the disabled ship told the Frankfurt operator that he was a fool.

Notwithstanding this, the captain of the Frankfurt said he would go to the Titanic's assistance. However, he could not be of any service due to the delay.

Carpathia to the Rescue

At the time of the collision, the Titanic was at latitude 41:16 north and longitude 50:14 west. This is approximately 450 miles south of Cape Race, 1,191 miles east of New York, and 1,799 west of Queenstown.

The Cunard steamship Carpathia, the only vessel to come to the rescue in time, was on its way to Mediterranean ports with many excursionists.

It was fifty-eight miles southeast of the Titanic when, at 12:30 a.m. of the 15th, its wireless operator, Thomas Cottam, who was just about to go off duty, heard the distress signal from the White Star liner. He verified it and notified Capt. Arthur H. Rostron at 12:35 a.m.

The latter put his ship about, ordered his crew and doctors to get everything ready to receive many shipwrecked persons aboard, and proceeded at full speed in the direction of the disabled vessel, the exact position of which had been given in the call for help.

Operator Cottam remained in communication with the Titanic, giving the position of the Carpathia and saying that it was hurrying to the rescue. The last message he received from the Titanic was: "Come quick; our engine room is filling up to the boilers."

Loading the Lifeboats

Having sent out calls for assistance and ordered the firing of distress rockets at frequent intervals, Capt. Smith and his officers took steps to notify the passengers of the danger and place as many of them as possible safely.

Messengers were sent to the various decks shouting, "All passengers on deck with life preservers on." The order was obeyed quietly and quickly, and so far, as known, all were aroused and equipped with life preservers.

The testimony is that there was a total absence of panic and little appearance of excitement. The ship was still and rode on an even keel except for a slight tilt forward. The lifeboats were uncovered and made ready to be lowered into the water by the captain's orders. The Senate report says:

"The lack of preparation at this time was most noticeable. There was no system adopted for loading the boats; there was great indecision as to the deck from which the lifeboats were to be lowered; there was wide diversity of opinion as to the number of the crew necessary to operate each boat; there was no direction whatever as to the number of passengers to be carried by each boat and no uniformity in loading them.

On one side, only women and children were put into the boats. In contrast, on the other side, an almost equal proportion of men and women were put into the lifeboats, the women and children being given preference in all cases.

The failure to utilize all lifeboats to their recognized capacity for safety unquestionably resulted in the needless sacrifice of several hundred lives that might otherwise have been saved.

"The vessel was provided with lifeboats for 1,176 persons, while 706 were saved. Only a few of the ship's lifeboats were fully loaded, while others were partially filled. Some were loaded at the boat deck, and some at A deck, and these were successfully lowered to the water.

The twentieth boat was washed overboard when the forward part of the ship was submerged, and in its overturned condition served as a life raft for about thirty people, including Second Officer Lightoller, Wireless Operators Bride, and Phillips, the latter dying before rescue - Col. Archibald Gracie and Jack Thayer, passengers, and others of the crew who climbed upon it from the water at about the time the ship disappeared.

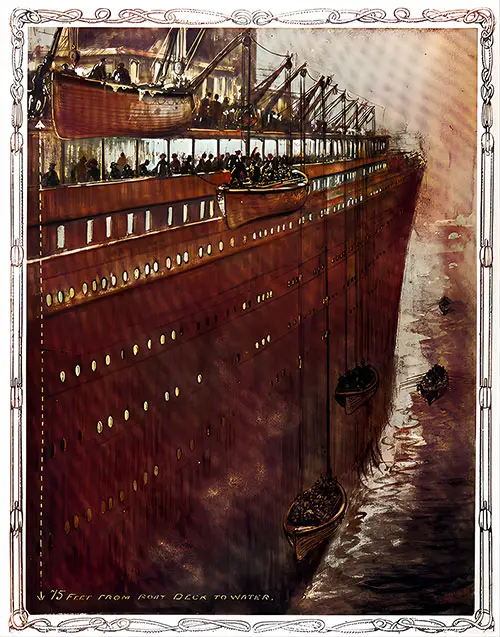

The Titanic's Boats Were Too Far from the Water. Had the Sea Been Rough, It Is Questionable Whether Any of the Lifeboats of the Titanic Would Have Reached the Water without Being Damaged or Destroyed. The Point of Suspension of the Boats Was about Seventy Feet above the Level of the Sea. Had the Ship Been Rolling Heavily, the Lifeboats, as They Were Lowered, Would Have Swung Out from the Side of the Vessel as It Moved toward Them, and on the Return, Roll Would Have Swung Back and Crashed against Its Side. The Illustrated London News (11 May 1912) p. 688. | GGA Image ID # 100aab983f

The testimony shows that there was no panic except in isolated instances. No distinction was made between first, second, and third-class passengers in loading lifeboats. However, the proportion of lost was more significant among the third-class passengers than in the other classes. Women and children without discrimination were given preference.

After the Order "All Men Stand Back Away from the Boats, All Ladies Retire to the Next Deck Below," Women Enter a Lifeboat from B Deck of the "Titanic." The Illustrated London News (18 May 1912) p. 755. | GGA Image ID # 100acff1a2

Women and Children First

Second, Officer Lightoller was in charge of loading six of the lifeboats, and he complied strictly with the "rule of the sea" that women and children should be cared for first.

There were fourteen lifeboats, capable of holding sixty-five persons each; two emergency sea lifeboats to hold thirty-five persons each; and four collapsible boats with a capacity of forty-nine persons each.

In the steerage, there was some crowding by the men, but it was checked by the officers and the crew, who obeyed the captain's injunction to "act like British men."

The men, whether millionaires or paupers, were equally heroic. They either stood back while the boats were loaded or helped in the work. This was notably the case with Maj. Archibald Butt, John Jacob Astor, Isidor Straus, Jacques Futrelle, and Henry B. Harris, all of whom perished.

Isidor Straus resolutely refused to enter a lifeboat, though asked to do so. "As long as a woman is on this vessel," he said, "I will not leave. When the women are safe, then come the men."

Mrs. Straus was petitioned to get in with the other women, but she refused to leave her husband and died with him. There were other instances of the same kind.

There was a feeling that the ship was in no immediate peril, and most married women went aboard the lifeboats under the impression that their husbands would soon follow them in other boats. Nothing was seen of William T. Stead. He is supposed to have remained in his room and gone down with the ship.

Band Plays as Ship Sinks

In the meantime, the Titanic was steadily sinking by the head, and the water was rising from deck to deck. The hundreds left on the ship were preparing to go down with it or -jump into the sea.

A few men were struggling to launch a boat that had become jammed, but nothing was being done. The eight musicians of the ship, who had come together while the lifeboats were being launched, continued playing to give the imperiled passengers confidence.

Even as the vessel was about to take its final plunge, the strains of "Nearer, My God to Thee" were heard. It was the most dramatic feature of the great tragedy.

It was 2:20 a.m. when the ship finally went down. Just as it was about to disappear, two explosions were heard, and to some, it appeared as though the vessel broke in two amidships.

The preponderance of evidence, however, is that when it went down, it assumed an almost end-on position and sank intact. The people in the nearest lifeboats heard loud screaming and moaning for what seemed to be several minutes, and then all was still.

Col. Gracie was one of the last persons on the ship as it sank. The suction drew him under the water, but some explosion in the vessel sent him and others to the surface.

He clung to a piece of wreckage until he recovered his breath. Then, he discovered the overturned lifeboat, which he managed to reach. He and another man helped others upon the craft, and at daylight, there were thirty men standing upon it.

They were knee-deep in water and afraid to move lest they upset and drown. Besides those mentioned in the senate report, quoted in a preceding paragraph, H. J. Pitman, third officer; J. G. Boxhall, fourth officer; and H. C. Lowe, fifth officer, were rescued in this manner.

First Officer Murdoch perished, as did Capt. E. J. Smith. The exact manner of their death is not known. It was reported, but not verified, that the former shot himself before the vessel sank.

The same was said of the captain, but this was declared to be untrue. Some passengers claimed to have seen him take a child in his arms and jump into the sea. A sailor said the child was taken aboard a lifeboat but that the captain sank.

J. Bruce Ismay entered one of the lifeboats before the ship went down and was saved. He claimed that no women were in sight then and that there was room for him.

After lowering, several lifeboats rowed for many hours in the direction of the lights supposed to have been displayed by the Californian. Other boats lay on their oars near the sinking ship, a few survivors being rescued from the water.

The sea was smooth, the stars shone, and the night was clear. It was cold, however, and those who were wet suffered severely. Many of the rescued were thinly clad, and some of them, including women, were glad to participate in the rowing to keep warm. One or more seamen had been assigned to each lifeboat to take charge of it.

After distributing his passengers among four other lifeboats that he had brought together and after the cries of distress had died away, Fifth Officer Lowe, in boat No. 14, went to the scene of the wreck and rescued four living passengers from the water, one of whom afterward died in the boat. The men who had taken refuge on the overturned lifeboat were taken off by lifeboats Nos. 4 and 12.

The fourth collapsible lifeboat contained twenty-eight women and children, primarily third-class passengers, three firemen, one steward, four Filipinos, J. Bruce Ismay and W. E. Carter of Philadelphia, and was in charge of Quartermaster Rowe.

RMS Carpathia To The Rescue

Brought across the Seas by Wireless to Aid the "Titanic," the Cunarder "Carpathia" Picked up the Only Passengers of the Ill-Fated Liner. The Illustrated London News (11 May 1912) p. 697. | GGA Image ID # 100c056ad4

The Man Who Saved Over 700 Lives through Sitting up a Little Later Than Usual: Mr. Cottam, the Wireless Operator of the "Carpathia" as a Student. The Illustrated London News (18 May 1912) p. 760. | GGA Image ID # 100c3ae183

It will be remembered that the "Titanic's" wireless call for help was received by the "Carpathia" sometime after the hour at which the latter's operator, Mr. Cottam, usually retired. Had he gone to bed that night at his usual time, it is said, the all would not have been hard, and probably few of the "Titanic's" people would have been saved.

After the wreck, Mr. Cottam worked for days without sleep under extra. The photograph shows him as a student at the British School of Telegraphy in Clapham Road, where Mr. Harold Bride also studied.

Captain Arthur Henry Rostron Next to the Silver Loving Cup Presented to Him in May 1912 by Survivors of the Titanic in Recognition of His Heroism in Their Rescue. Library of Congress LCCN 2014690409. | GGA Image ID # 100cc5cbfb

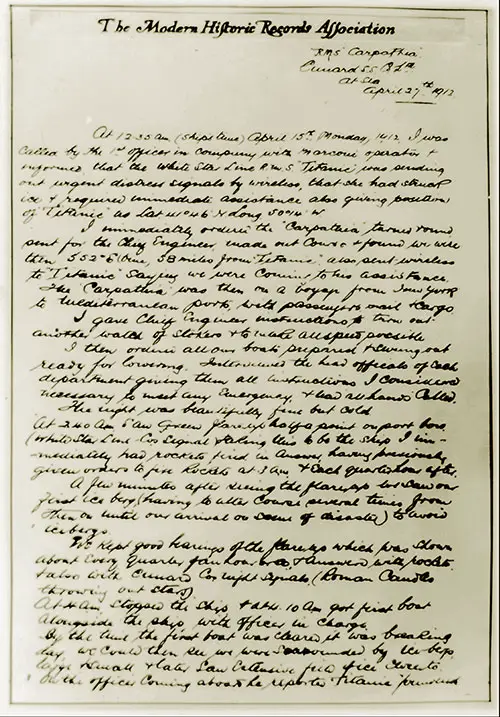

Photocopy of Hand-Written Account by Captain A. H. Rostron of the R.M.S. Carpathia Describing His Response to the Distress Signal of the Titanic on 15 April 1912. The Modern Historic Records Association. Library of Congress LCCN 2001704336. | GGA Image ID # 100d7296d0

Mrs. J. J. Brown Presenting Trophy Cup Award to Capt. Arthur Henry Roston, for His Service in the Rescue of the Titanic. Library of Congress LCCN 98509447. | GGA Image ID # 100c6a1f54

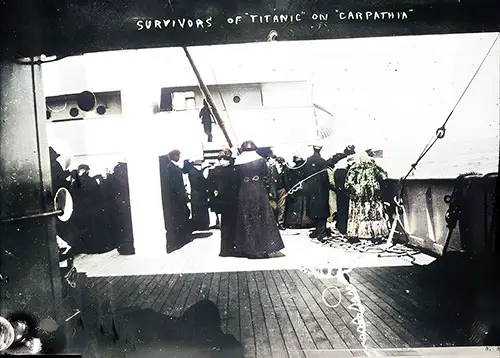

Rescued Titanic Survivors on the Carpathia

Group of Survivors of the Titanic Disaster Aboard the Carpathia after Being Rescued, 1912. Library of Congress LCCN 90707557. | GGA Image ID # 100d18f317

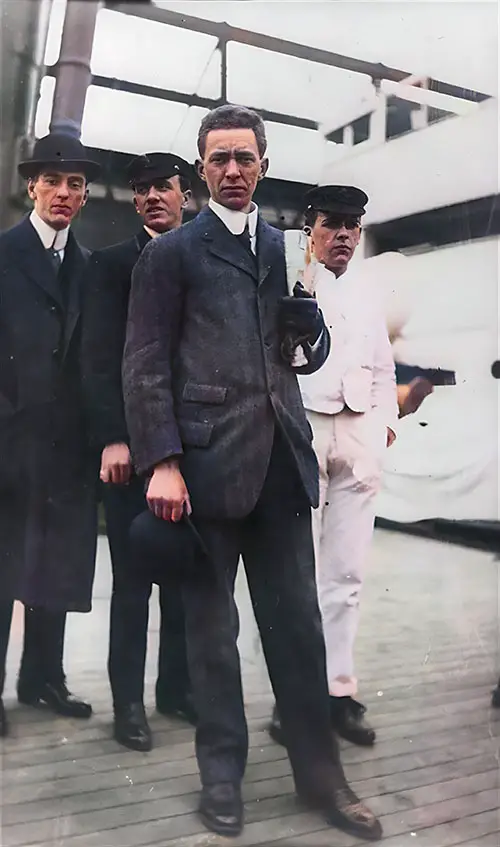

Stuart Collett - One of the Titanic Survivors Arriving on the Carpathia, April 1912. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress LCCN 2001704340. | GGA Image ID # 100d8af71a

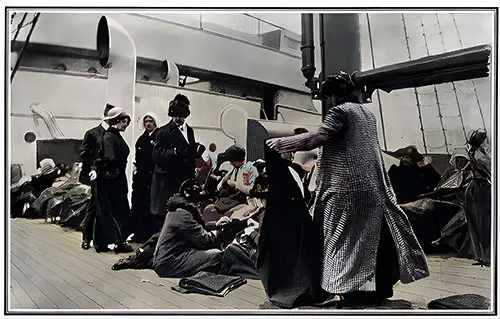

Assisting the Saved: Women Passengers on the Carpathia Sewing for the Titanic Survivors and Distributing Clothes, April 1912. The Illustrated London News, 18 May 1912. | GGA Image ID # 100e2d545e

Rescued Titanic Passengers Aboard the Carpathia, April 1912. Photograph taken aboard the "Carpathia" by Miss Bernice Palmer. Mr. George A. Harder, Who Was the Only Man Saved of Eleven Honeymoon Couples. Mr. & Mrs. G. A. Harder Talking with Mrs. Sollie Beck, formerly misidentified as Mrs. Charles M. Hays. Library of Congress LCCN 2002721378. | GGA Image ID # 100dc7846f

Mr. and Mrs. Harder were in the concert room listening to the music when the collision occurred. They heard the cry to man the lifeboats and, for fun, believing there was no danger, jumped into the first boat—very fortunately, as it turned out for themselves.

Mrs. Charles M. Hays, who was rescued, lost her husband, the President of the Grand Trunk Railway. His body was afterward picked up by the cable steamer "Minia" near the scene of the disaster.

Groups of Titanic Survivors Aboard Rescue Ship Carpathia, April 1912. Unidentified Group on Deck. Library of Congress LCCN 2002721379. | GGA Image ID # 100e939fef

The Rescue of Titanic Survivors

At 4 a.m., the lights of the Carpathia were seen, and all the boats rowed in the direction of the approaching steamer. The Cunarder had made good time, though forced to alter its course several times because of icebergs. At 4:10 a.m., the first lifeboat was picked up at 8:30 a.m., and the last survivors were aboard.

The day was breaking when the first boat was unloaded, and after that, the ocean surface for miles around was visible. Thirteen of the lifeboats were picked up and taken to New York. In his official report, Captain Rostron said that at this time, his ship was surrounded by large and small icebergs and that three miles to the northwest was a vast field of drift ice with large and small bergs in it.

At 8 o'clock, the Californian came up and was requested to continue the search for survivors or bodies. The Mount Temple also reached the scene in the morning and assisted in the search, but no bodies were found. It is believed that those subsequently picked up had been carried by strong currents away from where the Titanic went down or were hidden by the extensive ice.

At 8:30 a.m., the Carpathia started directly for New York. While the rescue work was in progress, a clergyman aboard offered a prayer of thankfulness for those saved and performed a short burial service for the dead. Everything possible was done for the wreck survivors, passengers, and officers, giving up their rooms and providing articles of clothing for those needing them.

The wireless equipment of the Carpathia could have been better, and more or less trouble was had to send messages ashore or to other ships. The regular operator, Thomas Cottam, was assisted by Harold S. Bride of the Titanic, who was saved in a crippled condition.

They confined themselves to sending official and private messages and the names of the rescued, paying no attention to requests for details of the disaster or even to the efforts of the operators on the United States scout cruiser Salem, who tried to get information on the fate of Maj. Archibald Butt for President Taft.

The operators on the Carpathia excused themselves later on the ground that the wireless men on the warship were incompetent and that it was a waste of time to reply to them. Because of this lack of definite information, the arrival of the Carpathia was awaited with much anxiety.

When the ship finally reached its dock in New York at 9:30 p.m., Thursday, April 18, it was met by a large number of people eager to welcome the survivors and to make inquiries about the missing. Those of the rescued who were ill or disabled were taken to hospitals. In contrast, others went to their homes or hotels to proceed to their destinations the following day.

Statement of Passengers from the Titanic

Upon the arrival of the Carpathia, a statement signed by a committee of twenty-five of the Titanic's passengers, with Samuel Goldenberg as chairman, was given to the press. After detailing briefly the facts of the wreck and giving approximately the number of persons on board, the number saved, and the number lost, the statement concluded:

"We feel it our duty to call the attention of the public to what we consider the inadequate supply of life-saving appliances provided for on modern passenger steamships and recommend that immediate steps be taken to compel passenger steamers to carry sufficient boats to accommodate the maximum number of people carried on board.

The following facts were observed and should be considered in this connection:

- The insufficiency of lifeboats, rafts, etc.

- Lack of trained seamen to man the same (stokers, stewards, etc., are not efficient boat handlers).

- Not enough officers to carry out emergency orders on the bridge and superintend the launching and control of lifeboats.

- Absence of searchlights.

- The board of trade rules allow for entirely too many people in each boat to permit the same to be properly handled.

- On the Titanic the boat deck was about seventy-five feet above water and consequently the passengers were required to embark before lowering the boats, thus endangering the operation and preventing the taking on of the maximum, number the boats would hold.

- Boats at all times should be properly equipped with provisions, water, lamps, compasses, lights, etc.

- Life saving boat drills should be more frequent and thoroughly carried out and officers should be armed at boat drills.

- Great reduction should be made in speed in fog and ice, as damage, if collision actually occurs, is liable to be less.

- In conclusion we suggest that an international conference be called to recommend the passage of identical laws providing for the safety of all at sea and we urge the United States government to take the initiative as soon as possible.

The Titanic Disaster of 1912

The Titanic Was Lost at Sea on April 15, 1912. Nelson's Encyclopedia (1907-1912) p. 87. | GGA Image ID # 105df14124

On Sunday, April 14. 1912, at 11:40 P.M. ship's time (10:45 p.m. New York time), the British steamship Titanic of the White Star Line struck an iceberg in lat. 41.46 N. and long. 50.14 w. (about 50O miles south of Newfoundland and 1,600 miles east of New York), and sank 2 hours and 40 minutes later, with a loss of about 1,500 lives.

The Titanic was on her maiden trip across the Atlantic Ocean and was in command of Capt. E. J. Smith. The night was clear and starlit, but it is claimed that the iceberg was so nearly the color of the water that it was not observed until only a quarter of a mile distant.

By a quick turn to port, a head-on collision was avoided. Still, the starboard side of the ship scraped along the sharp submerged ridge of the berg for a large part of her length, and her hold rapidly filled with water.

The shock is described as slight, and at first, some of the officers and most passengers did not believe the accident was serious. In half an hour, however.

Captain Smith ordered the lifeboats lowered to receive the women and children. There was slight confusion. The general confidence that the giant vessel was unsinkable caused the first boats to depart without their full complement.

The later ones were overcrowded. Wireless distress signals were sent from the Titanic, beginning about ten minutes after the collision and continuing until the water reached the wireless room.

Messages were received by the Carpathia of the Cunard Line (en route to the Mediterranean), the Virginian of the Allan Line, the Olympic and the Baltic of the White Star Line, and other vessels.

The Carpathia (58 miles distant), the Frankfurt, the Baltic, the Virginian, and the Californian headed under full steam for the disaster scene.

The Titanic began to settle at the head soon after the collision, and those who got off in the boats saw the lights extinguished on one deck after another as the water crept up.

When the bow was completely submerged, the stern rose high in the air, throwing hundreds off its crowded decks and swiftly disappearing. Several witnesses assert explosions just before the end, and the vessel parted amidships.

One of the lifeboats, returning to the spot where the ship sank, picked up several men clinging to rafts or wreckage.

The Carpathia reached the wreck scene about four o'clock on the morning of April 15, and four hours later, it had picked up the occupants of the fifteen lifeboats.

She then turned back to New York with her load of survivors. The other vessels speeding to the rescue, hearing from the Carpathia that they were too late to be of service, proceeded on their courses.

News of the disaster reached New York on Monday night, April 15. During the next three days, lists of the rescued were furnished by wireless communication.

President Taft ordered the U.S. cruisers Chester and Salem to convoy the Carpathia. Still, the latter changed her course to avoid the danger of icebergs.

The Carpathia reached her dock in New York at 9.35 on Thursday evening, April 18— the usual immigration and customs inspections having been waived.

The steerage passengers were cared for by a special relief committee and various other relief agencies, and public subscriptions were started by the mayors of London and New York.

When she cleared the port of Southampton on April 10, the number on board the Titanic was officially reported as 2,208. Of these, the first cabin passengers totaled 325; the second cabin, 285; the steerage, 708; and the crew, 890.

Of the rescued, 202 were from the first cabin and 115 from the second cabin—178 from the steerage, besides four officers and 206 of the crew. The number lost is estimated at 1,503.

Of the 705 saved, the majority were women, while more than half of the surviving men belonged to the crews that operated the lifeboats.

Notable Titanic Passengers, Saved and Lost. The Illustrated London News (11 May 1912) p. 687. | GGA Image ID # 1014e1e3ab.

Among the prominent persons who perished were Col. John Jacob Astor, head of the American branch of the Astor family; Major Archibald Butt, personal aide to President Taft; Jacques Futrelle. Author: Benjamin Guggenheim, member of the well-known Guggenheim family; Charles M. Hays, president of the Canadian Grand Trunk Pacific Railway; Henry B. Harris, theatrical manager; Frank D. Millet, artist; Washington A. Roebling, 2d. of the noted family of bridge builders; William T. Stead, the London editor; Isidor Straus, millionaire merchant and philanthropist, and Mrs. Straus, who refused to accept a rescue in which her husband could not share; John B. Thayer, vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad; George D. Widener and Harry B. Widener, of Philadelphia. Captain Smith and First Officer Murdoch went down with their ship.

Among those who were saved were the wives of many of the notable men who perished, including Mesdames John Jacob Astor, Jacques Futrelle, Charles M. Hays, Henry B. Harris, John B. Thayer, and George D. Widener. Others among the rescued were Col. Archibald Gracie and Countess de Rothes. Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, Lady Gordon, J. Bruce Ismay, Henry S. Harper, and Mrs. Harper.

The cable ship Mackay-Bennett, chartered by the White Star Line to cruise in the neighborhood of the wreck and search for bodies, arrived at Halifax on April 30 with 190 bodies on board, including those of Colonel Astor and Isidor Straus. In all, 300 dead were found, of which 116, chiefly members of the crew, were buried at sea.

On May 13, the Oceanic reported the finding of a collapsible lifeboat, the Titanic, containing the bodies of three men. The Titanic disaster directed public attention to the dangers run by liners in the ice fields and the inadequacy of the lifeboat facilities required by law.

The principal transatlantic lines agreed upon a course 270 miles south of the southerly route previously followed on April 19. Legislative steps were also taken in Great Britain and the United States to compel steamship companies to provide adequate protection for every person on board their vessels.

Courts of Inquiry

A subcommittee of the U. S. Senate Committee on Commerce, appointed to investigate the causes of and responsibility for the tragedy under the presidency of Senator William A. Smith, commenced its sessions in New York on Friday, April 19, and adjourned to Washington on April 22.

The witnesses subpoenaed included:

- J. Bruce Ismay, managing director, and P. A. S. Franklin, vice president of the White Star Line

- The wireless operators of the Titanic and the Carpathia

- The four surviving officers, 24 of the crew, and a number of the passengers of the Titanic

The testimony indicated that the Titanic had received several warnings of ice from other vessels—the latest from the Californian at five o'clock on Sunday afternoon; and that the ship was traveling at 21 knots (about 24 miles) an hour when she struck the iceberg.

It was further elicited that the Titanic did not carry sufficient lifeboats, that the boats left the ship only partially filled, and that no general alarm was sounded to warn passengers at the time of the accident. It was also shown that the supposedly watertight compartments needed to be watertight.

In its report on May 28, the Senate Committee blamed Captain Smith for ignoring repeated warnings about the proximity of ice. It blamed the management for its failure to provide proper life-saving apparatus.

It also criticized Captain Lord of the Californian for failing to go to the assistance of the Titanic. The British Board of Trade was criticized for lax regulations and inadequate inspection.

The Committee recommended that boat accommodation be provided for everyone on all seagoing ships and that ships be constructed with absolutely watertight bulkheads.

A court of inquiry appointed by the British Government to investigate the Titanic disaster opened on May 2, under the presidency of Lord Mersey, the Wreck Commissioner.

The witnesses were Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff-Gordon, Bruce Ismay, Captain Rostron of the Carpathia, Sir Ernest Shackleton, and Mr. Peskett, Naval architect to the Cunard line, several officers, sailors and passengers of the Titanic, and the chief officer of the Californian.

The main facts elicited at the American inquiry were confirmed. Still, the report of the British court, presented on July 30, was less severe in its censure than that of the American Committee.

It exonerated Captain Smith, blamed the Board of Trade for failing to revise its rules, criticized its methods of inspection, and made recommendations as to lifeboats and watertight bulkheads.

The matter of the neglect of the Californian to render aid was exhaustively investigated at the inquiry. Still, the report did not pronounce definitely on the culpability of her captain.

Details of the 'Titanic'

The Titanic, the largest ocean steamer ever built, a sister ship to the RMS Olympic, was constructed by Harland A Wolff in Belfast, Ireland, where she was launched in May 1911.

She was 882 feet 9 inches in length, 92 feet 6 inches beam, and 94 feet in depth. Above the casings, the funnels towered 62 feet, making the tall height from the keel to the top of the funnels 165 feet and the funnels above the grate bars of the furnaces 150 feet.

The Titanic carried 16 lifeboats and four collapsible boats but was provided with davits and launching gear for 48. The shell plates were of steel, 11 inches in thickness.

There were 11 steel decks and 15 transverse bulkheads, forming 16 watertight compartments when the bulkhead doors were closed. These doors were arranged to slide downward and were operated by hydraulic pistons under a pressure of 800 pounds per square inch.

When released by a control on the captain's bridge, they closed in 20 seconds. The Titanic had a draught when loaded, of 34 feet 6 inches. Her registered tonnage was 46,000, and her displacement was 66,000—1,000 tons greater than the RMS Olympic.

She was propelled by three screws, the two outer ones driven by compound reciprocating engines, each of 15,000 horsepower, and the central one by a Parsons turbine of 17,000 horsepower.

The cylinders of the reciprocating engines were 54-inch. 84-inch, and two of 97-inch, with a stroke of 75-inches. They were built to run at 77 revolutions per minute, with a boiler pressure of 215 pounds per square inch.

The turbine was run by the exhaust steam from the reciprocating engines and was not reversible. In one movement, the reversing lever cut off the supply of steam to the turbines while reversing the reciprocating engines. The steam was supplied by 29 boilers, 24 of which were double-ended.

The vessel's interior was fitted up as a hotel, with every luxury of modern life. Elevators connected the upper nine stories, also reached by spacious balustrade stairways.

There was a theatre, a swimming pool with nine feet of water, a palm garden and restaurant, squash, tennis courts, and miniature golf links on the topmost deck.

Some of the suites of apartments were most elegant, with a private promenade deck extending to the rail, and one commanded a rental of $4,350 for a single trip. The Titanic had accommodations for over 3,000 passengers.

The vessel cost upward of $5,000,000, and her fittings and furnishings cost nearly $3,000,000 more. She was insured for $3,700,000; her owners carried $750,000. The freight carried on the trip was but 1,500 tons. The total money loss of the disaster was estimated at not less than $27,000,000.

The Staggaring Loss from the Titanic Disaster. In 2018, the relative values of $27,000,000.00 from 1912 ranges from $517,000,000.00 to $14,700,000,000.00. Samuel H. Williamson, "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1790 to present," MeasuringWorth, 2019.

Lessons of the Disaster

It was clearly shown by the Titanic disaster that, while vessels are now built beyond the risk of foundering by wind or sea, there are accidents still liable to occur, which require passengers to leave the boat regardless of the condition of the sea.

The ever-present dangers of this sort are fire, collision with other moving vessels, and icebergs or derelicts. The larger the vessel, the stronger she is locally, and the greater the weight that can be spared to subdivide to prevent the spread of fire.

Of course, local strength is of significant protection in case of collision with a derelict. Assuming, however, that disastrous results will accompany accidents such as this, every precaution must be taken to avoid the accidents. Still, if they do occur, despite proper precautions, the evil of the loss of life must be made as slight as possible.

The one paramount lesson of the Titanic wreck is that more lifeboats could have saved many lives.

Although the stowing of boats is not a simple problem, at least twelve more could have been carried along the boat deck — six on each side in the space between the forward and after boats as carried.

It is not easy to stow them between decks, owing to the difficulty of swinging them out and the fact that the davits will interfere with lowering the lifeboats above.

The davits could run out with the boats, and as soon as the latter are free, they can be drawn back out of the way of the lifeboats above. The space and manner of supporting, lowering, and disengaging the lifeboats must be considered.

They must be dropped before reaching the water, and in this operation, both ends must let go at the same instant. The problems of getting the passengers into the lifeboats and the number of seamen available to handle them must also be considered.

Small boats are a great, bulky, heavy craft that experts must handle to be lowered safely in any sea. Modern deckhands are less capable of handling boats than the men of the sailing-boat and smaller-ship era.

This does not mean that they are not good men but that those required for the manning of a great steamship are selected mainly for a different sort of service.

Boats should be already fastened to their davits by falls, as such heavy objects cannot be handled by hand in an emergency. If lifeboats are stowed across the deck, they might be made much larger than at present and decked over by an ark-like top.

The opening could be temporarily closed after passengers had been put into such boats. Then, a derrick could lift the lifeboat and drop clear of the side. Such boats should have motors.

Since it has been found advisable to use motors in the life-saving service on shore, they will be installed on the ship's lifeboats.

Nowadays, there is always a larger percentage of passengers who can handle an automobile engine than of the crew who can efficiently handle an oar in a seaway.

Some part of the vessel built as a pontoon in which passengers can be placed, and which can be launched overboard, or which will float off if the ship is sunk, will meet many of the objections to small boats, which, had there been a sea on, would have saved but few of the Titanic's crew.

In a fog, a warning is usually given by the ship's whistle-sounding blasts at intervals. The echo from a berg of a ship's whistle can be heard and located with the geophone. Some noise can undoubtedly be made, which can be echoed from below the water, and the berg causing the echo situated in the direction of the present submarine bell apparatus on all modern vessels.

For the inventor, a well-known authority on shipbuilding has suggested the development of a small wireless apparatus of considerably different tension from the regular wireless outfit, by which vessels can feel one another out within twenty miles.

Also, a needle will place itself in line with rays sent out from another vessel—as they radiate in straight lines—and thus be able to indicate exact directions.

A Boynton suit rented like a deck chair would let passengers stay afloat in comparative safety for some time. With the great height of ships' sides, making a leap into the water dangerous, there should be shutes that could be lowered like gangplanks for safe descent.

The supplying of more boats would not necessarily ensure safety. Still, under circumstances similar to those of the Titanic disaster, it would give some who did not get it a chance and are entitled to such a chance.

Government can do much to promote all these ends by proper regulation, and so can the insurance companies.

The Wreck of a Titan - 1912

A Drawing by G. A. Coffin of the Sinking of the Titanic Last Monday Morning at Three a.m. The New York Observer (18 April 1912) p.488. | GGA Image ID # 100e9f1152

Two thousand fathoms beneath the waves of that part of the Atlantic which spreads itself in a waste of wintry waters to the eastward of Cape Race lies the great White Star Liner Titanic, sent helplessly to her ocean grave by one of those grim, uncharted terrors of northern seas—a giant iceberg. With her, too, lie buried 1,400 of the 2,200 souls with which she set out from Southampton on her maiden voyage to the West.

At this writing, a Cunard boat, the Carpathia, is steaming toward New York, having aboard 800 of the survivors of the most appalling disaster ever recorded in the world's maritime history.

Most rescued are women, indicating the men have gone down with the ship. The Carpathia picked up the survivors from the doomed liner's boats after hours of exposure in an ice-flowed sea.

All hopes that any other vessel had been able to rescue any of the Titanic's passengers were practically abandoned Wednesday when it was announced that neither the Parisian nor the Virginian, which, on receipt of wireless calls for aid, had been speeding toward the scene of the colossal tragedy, had anyone on board.

Thus, for the moment, we are left in awed and sorrowful contemplation of as fearsome a story as ever, the dark annals of the deep disclosed—one at which a man might stand appalled and a woman weep.

All day Wednesday, New York lay under the pall of an obsessing sense of desolation. As from the sea, news came stumbling in by dots and dashes, confirming and piecing out the details of the awful disaster; men and women stood aghast, forgetting for a moment their immediate concerns, and talked of nothing but the wreck.

Even the revelers on Broadway were silenced; the tavern-haunters sobered into abstinence. Perhaps not within living memory has news laid so restraining a hand on the unceasing movement of Manhattan as this story of a giant liner gone to her irrevocable doom.

Around the White Star offices, a great crowd gathered. Some were impelled by curiosity, some by sympathy. Others there were stricken through with apprehensive fear and sought with anxious inquiry and bursting hearts some scant message from the relentless sea.

In the presence of that awful happening on the banks of Newfound land, the sophistries and veneer of life, considerations of social position, influence, and affluence fell away as would an unloosed garment.

That crowd of almost frenzied inquirers was nothing more, nothing less, than sorrow-stricken men and women—waiting for news—just a scrap of news.

Outside the published list of survivors, all the authentic information yet to hand could be easily compressed into the limits of a single newspaper column. The story of the wireless has been necessarily fragmentary, intermittent, sufficient only to fill those for whom it meant most with alternate hope and despair.

But from the flashes of the Marconi grams and the brief accounts relayed by skippers of vessels who strove, yet vainly, to reach in time the sinking leviathan, something of the appalling disaster of Sunday to the Titanic, may with reasonableness be written.

Significantly, perhaps, for those who have traversed the great ocean highways—who have gone down to the sea in ships— it should not be difficult to frame at least some vague, qualified mind picture of the scenes enacted aboard the Titanic during those last few hours of her brief, ill-fated life.

It was Sunday night. A day, they had gone down over the broad expanse of wintry waters—for hundreds of the Titanic's passengers, the last they were destined to know this side of the resurrection morning.

Later, service would be held in the saloons, and voices would be raised in singing some familiar hymn loved by seagoing folk. Then, the comparative quiet of a Sabbath evening at sea would settle over the throbbing liner.

Down in the steerage, maybe, some Hungarian mother crooned a lullaby learned in the Austrian Tyrol to the fretful babe at her breast, or a blue-eyed Irish colleen sat with elbows on her knees and her face resting on her hands, thinking with tender memories of the green isle she had left behind her, dreaming of the great new land toward which her face was turned.

No thought, not even a suggestion of coming terror, no presentment or suspicion of the coming disaster—everybody resting in that extraordinary sense of security that permeates a trans-Atlantic liner.

Then, like a crash of echoing thunder would come that awful shock, flinging men and women from their berths and wrenching down the sumptuous fittings of that floating palace from their bearings and scattering them like leaves smitten by an angry gale.

Then the hurried scrutiny made by Captain Smith and his officers, the realization that the queenly vessel, which a moment before rode the waters of the Atlantic so proudly, had been dealt her death blow, the allaying, as far as possible, the terror of bewildered passengers by the devoted crew.

All this we know would happen, as British courage and discipline did what little could be done in the face of inevitable death. Then would come the inky darkness into which the doomed vessel would be plunged as the inrushing waters and failing dynamos blotted out her electric system.

Aided only by the feeble light of torch and lantern, every man would be at his post, lowering the lifeboats and placing the women and children in them. And what of those harrowing scenes of parting, as man and wife, sweetheart and lover, parent, and child, kissed a lingering, sobbing last goodbye? God pity them all! It almost breaks the heart to conjure up the scene.

Then, with no light in heaven save a few faint stars, the boats fared into the darkness, the white, sobbing women waving farewells to their men standing dimly outlined against the liner's rail.

Girt by formidable waves, with their present hope but little better than what it had been, holding only a slender belief in reaching the shore, the survivors drew away from the rapidly sinking vessel.

It is not difficult to imagine how, with tense, strained ears, they would listen, in the darkness, for sounds that would tell them that the Titanic had taken her final plunge, carrying with her into the caverns of the Atlantic those they held so dear; how they would shrink and shiver in the drenching of that long, night and hopeless dawn, until picked up by the friendly Carpathia and headed for home.

But what of those left on the sinking Titanic? Imagine that awful pause, dividing life and death—that wintry sea, dark, heaving, boundless, the image of eternity.

Then the plunge, when the sea yawned around the giant liner like hell and sucked her 'neath its whirling waves. Here and there, on the lip of the vortex, some strong swimmer, in his agony, would live a while—the rest were silent all.

Yet it is here that one finds a ray of slender light straggling through this dark scene of sorrow. These men died bravely, never faltering, upholding the best tradition of the Anglo-Saxon race, saving the women and children, dying themselves cheerfully, defending their honor, though at a price extremely dear.

It was no ignoble way to die, and the eyes of the world will turn in tender contemplation toward the lonely grave of the men of the Titanic, over which forever sweeps the unebbing sea.

Editorial Notes : The Titanic Inquiry

At more than one of its sittings, Senator Smith's Titanic committee indicated that had somebody possessing some knowledge of maritime affairs been employed to ask sensible questions, the dignity, if not the usefulness of those sittings would have been materially advanced.

Nevertheless, specific, well-established points were made, and some definite conclusions were reached. Among them were that the Titanic was running at almost her full speed when she struck the iceberg, that she had received ample warning of the nearness of the ice fields, that she had practically disregarded this warning, that there had been next to no test of the safety appliances before starting on the ill-fated voyage; that the number of lifeboats was sadly inadequate to meet the appalling situation created.

This much has been practically determined. Concerning the outcome of the investigation, it will lead, we trust, to a worldwide standardization of lifesaving appliances aboard ships of all nations; the standardization of wireless service by international agreement; the formulation of a code of procedure for wireless operators in case of disaster, and the fixing of much more rigid standards of inspection of steamships by American inspectors in American ports.

The United States is in a position to arbitrarily fix these standards of safety for all the world by insisting that no vessels be allowed to dock in American ports except those adequately provided with lifesaving appliances and apparatus.

Bibliography

"Sixteen Hundred Lives Lost on the TItanic -- With Photos," in Leslie's Illustrated Weekly: The People's Weekly. The Oldest Illustrated Weekly in the United States -- All the News in Pictures. New York: The Leslie-Judge Company, Publishers, Vol. CXIV, No. 2956, Thursday, 2 May 1912, p.506.

A. T. Merrick, "April 14, 1912. 11:45 p.m., Latitude 41 Degrees, 46 Minutes, Longitude 50 Degrees, 14 Minutes -- Drawing," in Leslie's Illustrated Weekly: The People's Weekly. The Oldest Illustrated Weekly in the United States -- All the News in Pictures. New York: The Leslie-Judge Company, Publishers, Vol. CXIV, No. 2956, Thursday, 2 May 1912, p. 502.

Henryk Arctowski, "The Deadly Meanace of the Iceberg -- With Photos," in Leslie's Illustrated Weekly: The People's Weekly. The Oldest Illustrated Weekly in the United States -- All the News in Pictures. New York: The Leslie-Judge Company, Publishers, Vol. CXIV, No. 2956, Thursday, 2 May 1912, p. 507.

James Langland, M.A. (Compiled by), "Loss of the White Star Liner Titanic," in the Chicago Daily News Almanac and Year-Book for 1913, Chicago: The Chicago Daily News Company, 29th Year, p. 151-155.

James Langland, M.A., (Compiled by), "The Rescue," and "Statement of Passengers," in the Chicago Daily News Almanac and Year-Book for 1913, Chicago: The Chicago Daily News Company, p. 153-154.

"Titanic Disaster." Nelson's Encyclopaedia: Everybody's Book of Reference. Vol. XII. London-Edinburgh-Dublin: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1912. 87A-88.

Nelson's Perpetual Loose-Leaf Encyclopedia was updated on a regular basis and the ©1907 included more recent entries such as the Titanic Disaster.

"The Wreck of a Titan," and "Editorial Notes: Titanic Inquiry," in The New York Observer, Vol. XC, No. 16, Whole No. 4641, Thursday, 18 April 1912, p. 483, 580.