Urgency of Improved Steerage Conditions - 1907

Kellogg Durland's article addresses the poor conditions faced by steerage passengers on transatlantic voyages. Through personal experiences and observations, it highlights the need for reforms to improve sanitation, accommodation, and overall treatment of passengers.

Based on the Personal Experiences of Kellogg Durland

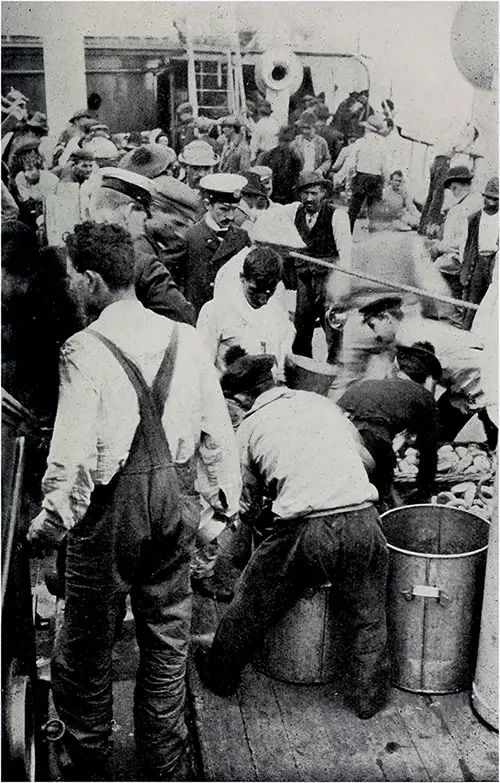

Preparing to Serve a Meal to Steerage Passengers on the Lahn from the Food-tanks and Bread-baskets. Broughton Brandenburg, Imported Americans 1904. | GGA Image ID # 1460613e26

Introduction

When our Government recognizes that the Americanization of our prospective citizens begins when they embark for our shores, and that the conditions which surround them in the steerage quarters of the mighty ships that bring them over seas produce the first impressions of American standards, steps will be taken to so improve and transform those conditions that the standard of living below-decks will be raised until it is compatible with decency, and American civilization.

At the present time the treatment of men, women and children in the steerage of certain ships coming from German, Mediterranean and Adriatic ports is far below this standard.

An acquaintance of mine crossed from Germany recently in the steerage of a ship, aboard which was a magnificent race horse, owned by a wealthy American horse fancier.

There being no better accommodation provided for this horse a loose box stall was contrived in the steerage quarters, in the same room where several hundred passengers slept and ate their meals.

My own experiences in the steerage of two English ships running between Mediterranean ports and New York clearly revealed how crying are the needs of the steerage.

More than one million four hundred thousand immigrants now come to us each year. The greatest majority of these come through the ports of New York and Boston.

In round numbers more than 800,000 come in ships whose steerage conditions are unsanitary, unclean, often indecent, and throughout unworthy. The steerage rates are exorbitant, out of all proportion to the first cabin rates in view of the relative conditions and privileges of these respective classes.

Traveling Incognito in Pursuit of the Steerage Experience

When I set out upon my investigation of steerage conditions I recognized the necessity for concealing my identity, so adopting the nondescript name of "Joe Nil," I dressed in clothes that were torn as well as dirty and old, and with a battered soft hat crushed over my face, which was effectually screened by a stubby beard, I boarded a ship in New York bound for Naples.

My real interest was in the conditions of the return trip, but I reckoned upon the out trip to familiarize myself with the general ways of the steerage decks, and to adjust myself to my unaccustomed role.

Any doubts I may have had concerning my disguise were speedily dispelled. At the head of the gangway a master-at-arms halted me to inquire if I had about my person what he called a "shot gun," and when I had told him "No," he inquired, in German, if I was an Italian. A moment later an Italian asked me if I was German.

The third class steward told me to join a Slovak group, and when I protested that I was English he changed me to the miscellaneous table where I sat down between a blackeyed Egyptian returning to his home in Alexandria and a portly Greek. While we were waiting for our first meal the company round the bare tables began to look each other over by way of prefacing acquaintance.

A young Italian opposite me looked over and asked abruptly :

"Where you conic from ?"

"I'm English," I replied.

"You lie !" he answered briskly.

"Then what do you think I am ?"

"Dunno. Europe somewheres. Maybe you Swiss."

After luncheon I rescued a small Italian girl from a perilous perch over an open hatch. Far from appreciating the kindness she hotly resented my interference and as she scampered off into the motley steerage crowd she kept calling "Sheeny !" "Sheeny !"

These incidents help to explain how it came about on the return trip that the Ellis Island authorities detained me for two days until the Board of Special Inquiry finally decided to deport me "as an undesirable alien."

They indicated that there was nothing about my appearance in any way unusual to the rank and file of my fellow passengers of the third class. Confidences were, therefore, quickly exchanged, and I think I was able to get pretty close to the steerage point of view.

The Voyage Begins

We were not yet out of Sandy Hook lightship when Dominick, a fine looking Italian whose bunk was next to mine, came and flung himself down on the same pile of wet hawsers where I was sprawling.

"Say," he began, "what's your name ?"

"Joe," I replied.

"Dominick my name."

Then there was a pause for a moment. Suddenly Dominick looked up at me :

"Joe, I go home to my country to get married."

"That's fine, Dominick," I returned. "How long have you been in America?"

"Three years."

"And has the girl been waiting for you all this time?"

Dominick looked puzzled and I repeated my question.

"She no wait. She don't know."

This time I was puzzled. Dominick thereupon explained that this was the dull season in the Brooklyn spoon factory where lie worked and he had been granted two months off to visit the old country.

In those two months he hoped to visit his old father and mother, to find a likely helpmeet for life, to woo, to win and to marry her !

During the three years he had worked in America he had saved several hundred dollars (saved out of his $11.00 a week). As he was now twenty-nine years old he thought it about time to marry and establish a home.

"By an' by be old," he said. "No wanta work. Can't work. If we have children -- they work, me no have to work."

"Why not marry an American girl?" I ventured.

A look of disdain came over his face.

"'Merican girl no good. Too much spenda de money. Too much Coney Island. Too much dance hall. Italia woman different. Italia woman work and sava de money. Puta de money in de bank. Me no want 'Merican girl for wife."

Dominick was typical of a class, I might almost call him a typical Italian. Italian immigrants, more than any others, preserve their roots in their native land. They hoard their money to send or carry back, they return then for their wives, and more than other people they go back for the last years of their lives.

Exploring the Steerage

The ship we were on carried a large steerage, for midwinter, and most of the passengers were Italians returning for a visit or to marry. The other nationalities altogether -- the Austrians, the Hungarians, the Bohemians, the Croatians, the Dalmatians, the Greeks and all the others, did not number as many as the Italians.

The vessel was of the Cunard Line, which in some respects is better than the German or Italian lines. We had tables to sit down to, for example, and we did not have to wash our own dishes as is usual on most other lines.

There were, however, some outrageous impositions. In our common dining room where more than 50o steerage passengers ate there were sixty occupied berths. When the ship is crowded this number is often increased to more than 200. But take sixty.

From New York to Naples is a trip of thirteen to fourteen days. On this particular trip storms raged for six days and nights. Many of the occupants of the sixty berths in the dining room were horribly seasick. I myself sat at a middle table in such close proximity to one tier of bunks that I had only to extend my arm to reach them.

We of the steerage were not being deadheaded to Europe. I had paid $30.00 for my ticket, and consequently I felt entitled to reasonably decent treatment.

The grand people in the first cabin had paid only $90.00 and sometimes first class passage can be bought for $75.00, yet the comforts and luxuries of the saloon are infinite compared to the steerage.

Steerage conditions must be crude, of course, and plain. But to stall a horse in a dining room, and keep it there for nearly a fortnight, and to lodge several score of seasick passengers in the dining room where all of the steerage is forced to eat is unnecessary and wrong.

My care, however, was not so much for the conditions on the out trip as on the return. Here, I found the conditions so much worse than anything I found going out, that I am inclined to pass lightly over these impositions for the present. They are bad, they should be attended to and corrected, but other matters are more urgent.

In the first place, the ships coming from Europe are more crowded. The passengers are for the most part densely ignorant of all ways of the world.

Thousands upon thousands of them have never been away from their own farms and villages before, and they submit to the treatment of cattle with the docility of ignorance. They don't like it, but they don't know any better. And here lies the whole trouble with the steerage question.

The steerage people submit to anything -- because they don't know what to do about it. The ships plying between Great Britain and America have provided decent steerage accommodations, staterooms for four and six, a dining room that serves no other purpose, a recreation room, clean sanitary conditions and proper food. All this should be provided on all vessels bringing aliens to our country.

The steamship companies, however, cannot be unduly credited with these improved conditions on the vessels carrying English speaking passengers. They are the result of constant and continued grumbling on the part of the passengers of past years, and of long agitation.

No one champions the Italians, the Slays and all the peoples of Eastern and Central Europe, and as they cannot express their dissatisfaction in any tongue understood by English-speaking officers they are forced to accept all manner of impositions. This is the reason why I suggest that some enterprising woman's club, or other organization, take up this matter.

The steamship companies would yield to pressure. They would cease to take unscrupulous advantage of people who cannot protest for themselves. And I know of no greater service that could be done America in connection with our vast so-called immigration problem.

Hundreds of immigrants accept steamship impositions meekly enough, every single month, but they remember later, how they suffered. Thus, the spirit of getting the better of someone, the spirit of graft, is their first impression of America.

The ship I sailed back from Naples on was a White Star steamer. I paid $36.00 for my ticket. There was no dining room at all provided, and we had to wash our own dishes -- which were of tin -- and absolutely no other provision was made for this than a barrel of cold sea water !

Sometimes I tried to scrape the greasy macaroni off my plate with my finger nails. Several times I was lucky enough to pick up a bit of newspaper somewhere for a dish cloth.

When we boarded the ship we found our "gear" (as our dishes were called) reposing in our bunks. Each passenger's "gear" consisted of one tin saucepan, one tin dipper, a tin spoon and a tin fork. Nothing else. Not even a knife. Each passenger is supposed to retain his "gear" throughout the trip, and to take entire charge of it himself.

Meals in Steerage

The Steerage Bread Line. Heads of Groups are in Line to Have Their Pails Filled. The Home Missionary, March 1908. | GGA Image ID # 1469455e76

The entire steerage was divided into groups of four, six and eight each. Each of these groups appointed a captain to go to the galley at each meal to receive the dole of food for the entire group.

These groups make themselves as comfortable as they can -- anywhere. Sometimes on a hatch, sometimes on deck, sometimes in their bunks. The steerage is not provided with means for sitting down so usually the meals are eaten on the floor.

After the food of each group has been apportioned every man shifts for himself -- or goes without if he can't stand the filth and the smells and the discomforts.

I shall never forget the first meal I received on this boat. We had left Naples late in the afternoon. The rent in the side of Vesuvius was already beginning to glow blood red.

About dusk we were called to the galley. I had not joined any definite group at that time so taking my gear in my hands I lined up with the long row of captains down the galley passageway.

The food was being dispensed from the galley by two Italian stewards. When my turn came to receive the dole I had to brace myself considerably. The first steward was a dirty, middle-aged Italian in a filthy shirt.

A hand soiled with all kinds of dirt -- ship dirt, kitchen dirt and human dirt -- pulled a great "cob" or biscuit out of a burlap sack and shoved it towards me. Then he snatched up a tin dipper and filled it with coarse red wine. As he handed this to me he sneezed -- into the hand from which I had just taken my biscuit.

That sneeze cane nearer to being My undoing than six days of storm on the out trip. I passed quickly to the next man who slopped a dipper of macaroni soup into my saucepan.

This was the complete meal, and every bit as good as the best meal I had on the whole trip. There is no complaint about the quantity of the food, but the quality, and the way that it was served was not fit for human beings.

I am not in the least hypercritical here. I can, and did, more than once, eat my plate of macaroni after I had picked out the worms, the water bugs, and on one occasion a hairpin.

But why should these things ever be found in the food served to passengers who are paying $36.00 for their passage? Such gross carelessness is indulged in only because the White Star Steamship Company knows that the steerage people are not in a position to lodge any material complaint or to make any serious objection.

Sanitary Arrangements in Steerage

Another matter of importance is in regard to the sanitary arrangements. These were entirely inadequate to the number of passengers. Even the washing facilities were hopelessly few.

Often I would wait half an hour for a basin, and sometimes, when the ship was rolling and the atmosphere of the washroom became so close and fetid that I could not hold out against it I omitted my morning ablutions entirely.

I did this less frequently than scores of my fellow passengers, however, for I found that on the whole I was better able to stand steerage hardships than many men, and much better than the women, who have never been to sea before and are painfully ill the whole way across.

I shall not go into detail in regard to the lax methods of some companies in regard to keeping the sexes distinct. I have heard many an outrageous story, however, of peasant girls being maltreated in the steerage of vessels bringing them to this country.

It is impossible within the compass of one short article to go into the details of the voyage, or to dwell at any length upon the various evils of steerage conditions.

What I hope I have been successful in doing here, however, is to indicate that reform is necessary, and in pointing out some of the specific delinquencies of the steamship companies showing that these reforms are of a very practical character.

Summary and Conclusion

During the year which ended in June, 1907, more than 1,400,000 immigrants came into the United States. Our own immigration authorities are handling this enormous multitude with rare skill.

The Ellis Island Station, under the supervision of Commissioner Robert Watchorn has attained a splendid standard of efficiency. Each year now the immigration "problem" with us is more and more becoming a question of distribution.

The question cannot be left to the comparatively small force of the Department of Immigration, though. It is a national question in every sense. And it begins not merely at our portals, but across the water, at the point where the immigrants board the ships to come to us.

It has been shown that steerage conditions are improved when the pressure of public opinion is brought to bear upon the steamship companies.

Inasmuch as this is such a vital matter with us -- this focusing of right American influences upon our would-be citizens at the earliest possible moment -- the value of any work that will stimulate or accomplish this is obviously inestimable.

Conclusion

Durland emphasizes the critical need for immediate improvements in steerage conditions. He advocates for better hygiene, accommodations, and enforcement of regulations to ensure the humane treatment of immigrants. The article calls for public pressure on steamship companies to address these issues, recognizing the impact of these conditions on immigrants' perceptions of America.

Key Points

🔍 Personal Investigation: Durland's undercover journey reveals poor conditions.

🧳 Overcrowding: Excessive passengers with inadequate facilities.

💧 Sanitation Issues: Poor hygiene and insufficient washing facilities.

🍲 Food Quality: Low-quality meals served in unsanitary conditions.

🚢 Steerage Experience: Describes harsh treatment and lack of privacy.

🛠️ Reform Advocacy: Calls for improved regulations and facilities.

🌍 Immigrant Treatment: Reflects broader societal attitudes towards immigrants.

📊 Public Pressure: Urges public advocacy for better conditions.

👥 Cultural Impact: Highlights the lasting impression on immigrants.

📜 Historical Context: Reflects the early 20th-century immigration issues.

Summary

-

Overview: Durland's investigation reveals deplorable steerage conditions, emphasizing the need for reforms.

-

Personal Journey: Undercover, Durland experiences overcrowded, unsanitary conditions.

-

Food and Sanitation: Poor-quality food and inadequate sanitation are highlighted.

-

Passenger Treatment: Immigrants face harsh treatment and lack of privacy.

-

Call for Reform: The article advocates for immediate improvements in regulations and facilities.

-

Public Advocacy: Emphasizes the importance of public pressure on steamship companies.

-

Cultural Impact: Discusses the negative impact on immigrants' perceptions of America.

-

Public Awareness: The article aims to raise awareness of the issues.

-

Historical Significance: Reflects broader societal issues and attitudes.

-

Conclusion: Urges reforms to ensure humane treatment of immigrants and improve their experience.

"Urgency of Improved Steerage Conditions Based on the Personal Experiences of Kellogg Durland" in The Chautauquan: The Magazine of System in Reading, Chautauqua Press, Chautauqua, New York, November 1907, Volume 48, Pages 383-390+.