The Conventions of Mourning in America - 1910

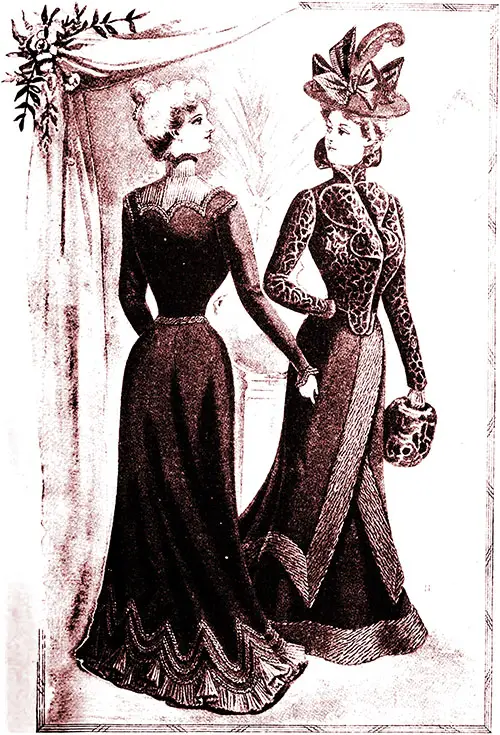

Handsome Mourning Costumes. The Delineator, January 1900. | GGA Image ID # 2178bfce7c

By Eleanor Chalmers

Overview of Mourning Customs

It is important to understand mourning customs as they show respect for the deceased and their family. Although these customs are not universally observed, they still hold significance.

While many women are aware of the customary mourning practices, they sometimes choose to ignore them. This is because Americans are fundamentally unconventional people, and many do not place much value on the symbolism of grief.

Mourning is a deeply personal matter, and everyone should be free to choose how they express their grief. However, if one decides to observe mourning customs, it is important to be aware of what is considered appropriate.

Appropriate Duration and Depth of Mourning

I often receive letters from people who ask me about the appropriate duration and depth of mourning to be observed for different family members. The most profound grief is experienced by a widow for her husband.

It is customary for a widow to wear deep mourning for a year or eighteen months, during which she wears dull and lusterless materials such as Henrietta or cashmere, trimmed with crepe.

The widow should wear a small Marie Stuart bonnet of black crepe with a ruching of white crepe next to the face. However, the crepe veil should be attached to the back of the hat and should no longer be worn over the face. This is a practice that has fortunately gone out of style, as it is both physically and mentally unwholesome.

In the second phase of mourning, the crepe veil should be replaced by a silk grenadine edged with crepe folds. The widow lays aside crepe but wears dull-finished black fabrics for six months or a year. Many widows choose to wear second mourning for the rest of their lives.

If one prefers a small toque instead of a hat or bonnet, the widow's ruché can be used at the brim. Many of the tiny hats are under the face of white crepe.

Practical and Appropriate Mourning Attire

When a person is mourning, it is important to choose practical and appropriate attire. The widow's dress should be simple and elegant, made of the best quality material that one can afford. Poor quality black fabric can quickly lose its look and become shabby.

For deep mourning, materials like Henrietta and cashmere are ideal. During the second stage of mourning, lighter and more translucent fabrics like chiffon and silk tissues can be worn. Understanding the different stages of mourning can help one prepare and choose the right attire accordingly.

White Organdy or White Crepe

Widows wear deep cuffs and collars of sheer white organdy or white crepe for first and second mourning. The organdy cuffs and collars are usually not hemstitched or even hemmed.

Instead of hemming, the hems are folded and then the cuffs and collars are basted to pieces of black crinoline or buckram that are cut to fit the neck and wrists. The hems are placed between the buckram and the cuffs, which stiffens the organdy and prevents it from wrinkling, making the cuffs and collars set more neatly.

The organdy cuffs are four and a half inches deep and finished. The hems are an inch and a half deep and there is an inch and a half space between them. They can be sewn together with three small pearl buttons at their back edges, and it is not necessary to create buttonholes.

The Collar’s Depth and Mourning Accessories

The collar's depth depends on the size of the neck. It's usually two inches deep, and it's finished with a hem three-quarters of an inch deep. The white crepe sets are sometimes made of bias folds of the crepe that are fagoted together or used at the edges of tucked lawns, net cuffs, or collars.

The white crepe sets can be cleaned with gasoline, which is quite fortunate since white crepe is expensive. On the other hand, organdy can be purchased at a reasonable price, ranging from seventy-five cents to a dollar per yard.

When it comes to mourning accessories, it is important to note that they don't have to be highly expensive. For example, organdy collars and cuffs are not very costly, and although they cannot be laundered and must be replaced daily, they can be purchased in lovely quantities at a reasonable price.

Accessories Typically Worn During Mourning

In addition to black clothing, there are several other accessories that are typically worn during mourning. These include suede gloves, dull kid shoes, and face veils made of grenadine or net. The veils are usually bordered with black grosgrain ribbon or crepe that is half an inch or an inch wide.

It is important to note that colored jewelry is never worn during first, second, or half mourning. However, pearls and diamonds, black enamel cuff pins, and gun-metal belt buckles are acceptable. Gold, silver, and colored jewels are not. Black-bordered handkerchiefs are not as commonly used as they once were, and the ones that are in use have narrow borders.

When it comes to mourning stationery, the best form calls for a narrow black border on cards and notepaper. However, the large borders used abroad are considered rather ostentatious in the United States and are therefore avoided.

Black furs such as lynx and Astrakhan are the typical furs worn during mourning. White, brown, or gray furs should not be worn. Sable has always been accepted as the equivalent of black. Bands on the sleeves are only worn by servants or people who cannot afford proper mourning attire.

Grieving for a Loved One

When someone is grieving for a loved one, they may wear mourning clothes for a certain period of time. The clothes worn by a mother for a grown child or by a grown child for a parent are similar to those worn by a widow, but with some differences.

For example, a toque or hat is worn instead of a Marie Stuart bonnet, and the cuffs and collars are not as deep. There are two types of mourning: deep mourning and lighter mourning. Deep mourning is worn for six months to a year, while lighter mourning is worn for the following six months to a year.

However, if the person mourning is a young child, the period of grief can be shorter. If a young girl is mourning for a parent, she does not wear a crepe veil and may or may not wear crepe on her dresses. She generally wears deep black for a year and lighter mourning for six months.

If a young girl is wearing all white, this is considered full mourning, although it is not as deep as black. White cashmere, poplins, wool batistes, and albatross are used for house dresses.

White serge and Cheviot, linen, India silk, cotton batiste, and organdy – in fact, any plain finished white material – constitute white summer mourning.

Lingerie or Embroidered Materials

No lingerie or embroidered materials are used, and the mourning character of white Winter dresses can be emphasized by white crepe. This beautiful material lends itself admirably to trimming purposes. Black and white is only half-mourning; in fact, smartly gowned women wear it so much nowadays that it is hardly suggestive of grief.

Complementary Grief

When a brother or sister passes away, full mourning is observed for a year, but it is not as deep as the mourning observed for a parent. If mourning clothes are worn for a grandparent, they are typically worn for six months. For an aunt or uncle, mourning clothes are worn for three months.

This type of mourning is called complementary grief and is strictly observed in other countries. However, in some cases, it is entirely disregarded in our culture. The degree of closeness between family members should determine its use.

Sometimes, a grandparent or an aunt or uncle may play the role of a parent to an orphan. In such a scenario, the same mourning practices should be observed for them as they would be for a parent.

Showing Grief and Respect for the Dead

Mourning is a time to show grief and respect for the dead. Therefore, it should always be done with dignity and without drawing too much attention. Wearing flashy or attention-grabbing clothing is not appropriate.

During the period of mourning, one should withdraw from formal socializing. Although condolence visits are acceptable, one should not entertain guests or visit others during this time.

After six months, one can start attending concerts or the theater. While some people prefer to avoid entertainment during mourning, it is advisable to engage in activities that can help take one's mind off the grief.

Use of Crepe and Materials for the Yoke and Chemisette

I have received numerous inquiries regarding the use of crepe and the selection of materials for the yoke and chemisette. Therefore, I would like to discuss these topics before concluding the subject of mourning attire.

The most common application of crepe is in bands or circular ruffles at the lower part of skirts. The modern crepes are lightweight and flexible, and even a knee-deep frill does not cause any discomfort. Many crepes available nowadays are waterproof and more durable than those from previous generations.

However, it is important to brush them well as they tend to accumulate dust. Black fabrics require more care and attention compared to colored fabrics, or they will become gray and shabby.

Crepe can be used as bands and berthas on waists, yokes, and chemisettes. It can also serve as collar facings on coats and coat dresses, piping, or bands on top of plaited flounces. Additionally, it can be used as an underskirt beneath a tunic or as trimming on the tunic.

Girdles, Oversleeves, Yokes, and Semitransparent Chemisettes

Girdles and oversleeves are typically made of certain materials, such as lusterless silks like peau de soie, ottoman, bengaline, or faille. These materials are also used for minor things like buttons and rosettes. When it comes to coat collars, crepe is a common choice, but other lusterless silks can be used as well.

In deep mourning, yokes and semitransparent chemisettes are often used and they are always black. They can be made of materials like crepe, chiffon cloth, tucked chiffon, or silk net. Lace is never used on them.

Separate blouses can be made from different materials, such as peau de soie, crepe de Chine, or chiffon. For everyday wear, black challis tucked waists can be worn with serge skirts, white collars, and cuffs. They are practical and good-looking.

Mourning for Children and Men

I haven't mentioned anything about mourning for children, as there's a strong aversion to it in this country. Girls aged twelve or fourteen may wear black clothing to mourn a parent, sibling, or sister, but it's not compulsory even at that age.

Mourning is not as significant for men as it is for women. A man who becomes a widower wears a thick band on his hat, regardless of the hat type, for a year. He refrains from attending social events for six months or one year, and usually wears black clothing for a year.

He also wears a thick band on his hat to mourn a parent or child. So many American men don't wear mourning clothing at all that there's hardly any general custom regarding it.

Based on an Article by Chalmers, Eleanor, "The Conventions of Mourning," in The Delineator, New York: The Butterick Publishing Company, Vol. LXXV, No. 3, March 1910, p. 243-244.