Reducing the Human Cost of War - 1944

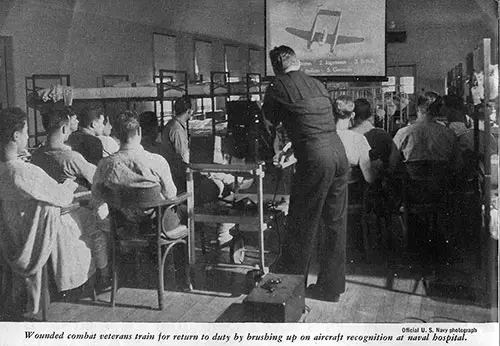

Wounded combat veterans train for their return to duty by brushing up on aircraft recognition at the naval hospital. (Official U. S. Navy photograph)

Navy Rehabilitation Program Refits Disabled Men For Further Military Duty or Return to Private Life as Strong, Useful, Self-Sustaining Citizens

Because the last war was relatively short, complete attention was not given the subject of rehabilitation until the war was over. Many lessons have been learned from that experience.

There is a different concept this time. Vice Admiral Ross T. Mclntire, (MC) USN, Surgeon General of the Navy, expresses it this way: “Proper rehabilitation starts the day a man is wounded or breaks down."

In line with this, the Navy has developed a broad program which involves many new ideas and is showing bright promise. The goal is what the doctors call “maximum adjustment”— that is, putting men back into the finest shape possible, either for further military service or return to civilian life.

If a man is to return to active duty, then the intention is to send him back better prepared than when he entered the hospital, better able to play his part in the Navy.

For the man awaiting discharge, the goal is to return him to civilian life with the least possible handicap from his disability and the highest possible preparation for life as a civilian.

Disabled men returned to civilian life will have their disability allowances, it is true. However, as the Surgeon General has said, they must not be led to believe they should live on the money paid them as a pension.

The Navy program tries to develop abilities to counterbalance disabilities and to instill in every disabled man the determination to play a useful role in his local community.

Rehabilitation in this light consists of turning out men who are strong, self-reliant, self-sustaining and self-confident, men who can get along in any company. This is important both to the man himself and to the nation as a whole.

The plan is to provide complete medical and surgical treatment and supplement this with training and welfare services which go beyond ordinary hospital care. For these, the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, whose responsibility the rehabilitation program is, calls upon the Bureau of Naval Personnel.

Thus expert help and guidance is invoked at once on behalf of any man who is incapacitated. This new type of human “damage control” goes into action regardless of whether the man can be restored to duty or must be discharged to civilian life. The heartening news is this: The human cost of the war is being reduced.

Program Expanding

Work along these lines has been underway for several months in the general and convalescent naval hospitals now operating within the continental limits, and the program is now expanding, with additional personnel, both officer and enlisted, under training for special phases.

In April, the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery established a new branch devoted especially to rehabilitation and ordered naval hospitals within the continental limits to appoint one member of the staff as a rehabilitation officer.

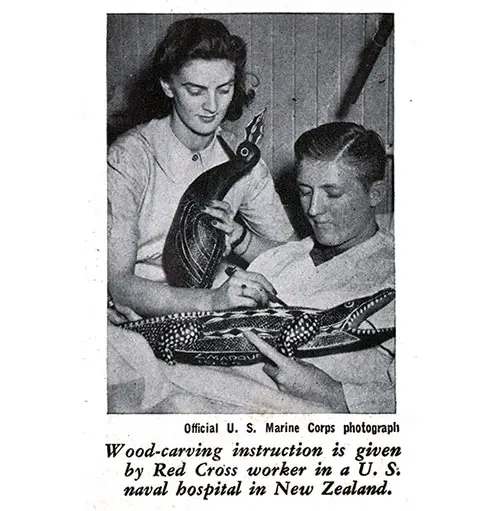

Usually, he has the attendants of a rehabilitation board, representing every branch of modem medical knowledge. On these boards, along with men skilled in such things as surgery, neuropsychiatry, and physiotherapy, there are non-medical men versed in such things as vocational guidance, physical education, and recreation. There are also Red Cross workers and chaplains.

No matter whether the patient's destination is a duty station or a discharge, he finds that within his limitations life in a naval hospital ha9 been made active rather than passive. The picture is one of business and industry, and that is true even for men confined to their beds.

There is a brand-new conception of how much a patient may accomplish while “laid up.” Educational services officers and physical training officers work hand in hand with the doctors. Training devices are becoming almost as much a part of hospital furniture as beds.

Physical training experts, working under the doctors’ supervision, show patients how to keep in good trim, though they may not be able to leave their beds.

Patients take exercise regularly, in prescribed amounts — not only the corrective exercise they may need to limber up after an injury but the kind of training that maintains ordinary physical fitness.

This exercise is designed to fit the needs of the individual, for the program is personalized, not routine. Additional experts are now being trained for this by Bu- Pers’ Physical Training Section.

Training Resumed

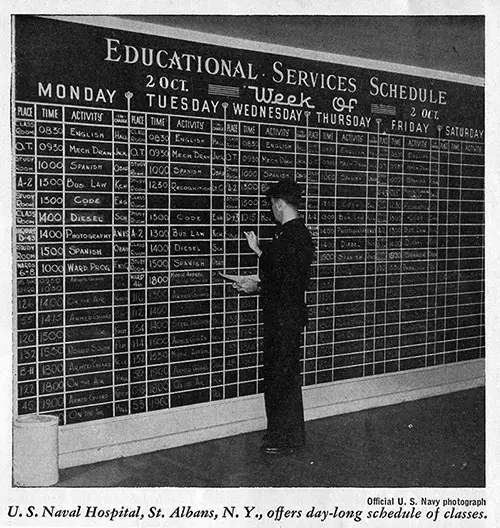

U. S. Naval Hospital, St. Albans, NY, offers a day-long schedule of classes. (Official U. S. Navy Photograph)

Whenever medical men say the patient is ready, he resumes the training that was interrupted by his illness or injury. He is shown that he need not go stale, but on the contrary, can advance.

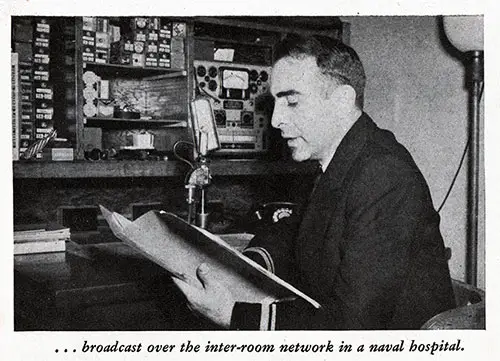

Officers operating under the program of BuPers’ Educational Services Section bring the Navy training program right to the patient’s bedside.

Training of one sort or another starts as early as the patient’s condition permits, and the tempo increases in step with his recovery. By the end of his convalescence, he is performing the equivalent of full duty.

Patients now “get better” in several ways, not merely in the sense of improved health. Training devices of all kinds are provided, ranging from semaphore flags to walkie-talkies. Ambulatory patients work out navigational problems, assemble radio sets, learn aircraft recognition or practice with blinkers.

If the man was studying for a higher rating when incapacitated, the educational services officers see to it that he loses no ground. Many men complete their study for advancement in rating and take the written part of the examination for promotion while still patients.

High school or college work is made available, and patients often fill in gaps in their schooling or learn something new for postwar use.

Just what portions of training and exercise to mix with medical and surgical treatment is, of course, for the doctors to prescribe, as only they may prescribe physical or occupational therapy. Every man’s daily program is tailored to his case.

The supplemental activities are not permitted to become a burden. He is shown, however, how he can keep his time occupied for a useful purpose. This gives him a sense of accomplishment and combats hospital tedium. Experience indicates that this new prescription speeds recovery.

There is no room for boredom or “hospitalitis” or mental unemployment. The slump in the physical condition which often accompanies forced idleness is averted to a great extent. These men are “down,” but they are by no means out.

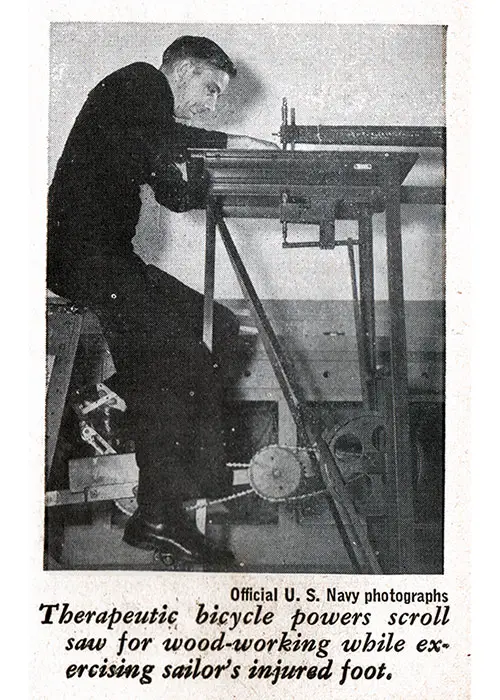

Therapeutic bicycle powers scroll saw for wood-working while exercising sailor’s injured foot. (Official U. S. Navy photographs)

The primary aim is, of course, to restore men to active duty, and to do so as rapidly as wise medical practice permits. To bring a man to the right state of training takes time, making his training essential to use while on active duty.

The man wounded in combat is a battle-tempered man of apparent value. Aside from the humanitarian aspects, there are urgent military reasons for getting skilled men back to their duty stations with the least possible delay, and at the highest possible pitch of health, spirits, and ability.

With approximately 67.500 men in naval hospitals within the continental limits, as of 20 October 1944, the value of this is evident.

It means a good deal to a man who has made the Navy his career or is fired with intense patriotism, to know that an injury received in combat is not necessarily going to put him on the shelf. It is the Navy's policy to retain him in duties compatible with his ability.

The statistics on the rehabilitation of the wounded are striking. It speaks well for the skill of the Medical Corps that of 30,000 Navy and Marine wounded up to 30 June 1944, and only 443 had to be invalided out of the service.

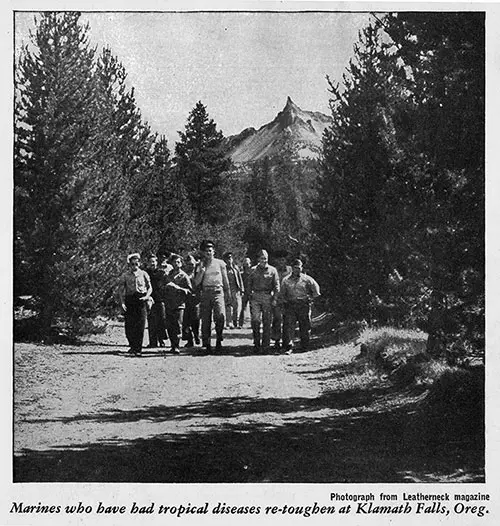

Marines who have bad tropical diseases re-toughen up at Klamath Falls, Oregon. (Photograph from Leatherneck Magazine)

The early campaigns produced a good many cases of tropical diseases. This problem resulted in the creation of the new Marine barracks at Klamath Falls, Oregon. This is an establishment of an entirely new type, neither hospital, convalescent home nor rest center.

The men on duty there are not patients and are not so regarded, although medical care is immediately available. They are marines who contracted tropical diseases while fighting in the Pacific.

Some had spent more than a year in various hospitals, although they needed medical attention only at intervals, and needed primarily a chance to rebuild their strength. It was an enervating, discouraging experience.

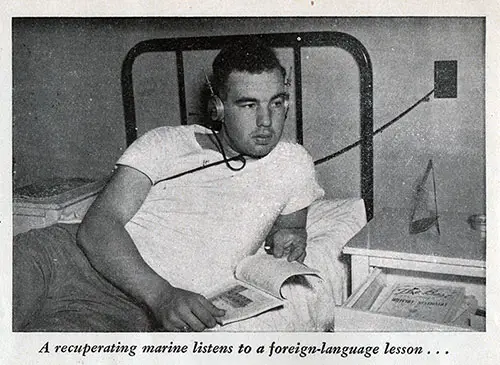

A recuperating marine listens to a foreign-language lesson

This station was set up on 18 January 1944, under Col. Bernard Dubel, USMC, and at present 2,700 men are on duty there. Their program combines medical treatment when and if they need it, with the regular responsibilities of marines anywhere. As fighting men, they keep their hand in.

There is also a great deal of sport, for the barracks lie in a mountain basin 5,000 feet above sea level, in excellent hunting and fishing country. However, the Klamath Falls camp is not a recreation center. The men keep exceedingly busy.

As they regain their old power, the work grows progressively more vigorous until they are taking 12-mile hikes up the mountains under a full pack. The first large group of men moved in on 29 May. They have responded so well that the majority of them are going back to service— and for unlimited duty.

Rehabilitation for Discharge

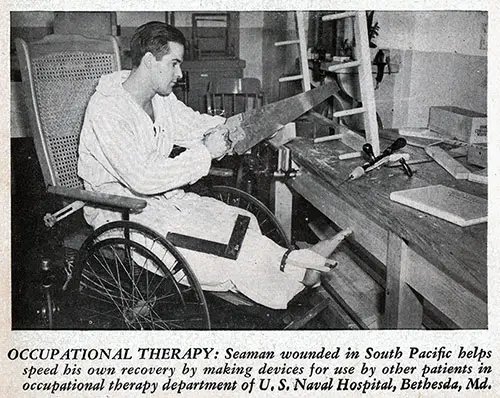

Occupational Therapy: Seaman wounded in South Pacific helps speed his recovery by making devices for use by other patients in occupational therapy department of U, S. Naval Hospital, Bethesda, Md.

For the man awaiting discharge the question looming largest is that of a job. The Navy tries to see to it that he has a planned future. If he knows what he intends to do, he can use his stay in the hospital to get into a high state of readiness.

The educational resources of nearly 100 colleges are available to him through correspondence courses, and Navy educational services officers provide material on any subject in which the patient shows an interest. Patients study everything from electronics to turkey raising and homesteading prospects.

Many a man about to be discharged is at loose ends, with little or no idea what he would like to do or what he is fitted for. In this case, he can get expert guidance and realistic advice.

Educational sendees officers and psychologists review his training and experience, test his aptitudes and preferences, and sound out his ambitions. If he has physical or psychological handicaps, they are carefully evaluated.

. . . broadcast over the inter-room network in a naval hospital.

He is given a thorough personal inventory, and the most modern techniques are used to assist him in determining the kind of work at which he has the best chance to prosper. Men worried about their lack of experience usually are surprised at the variety of jobs a trained vocational expert can unfold for them.

One of the patients in an eastern naval hospital is a seaman who was injured in a shipboard accident. He is young, inexperienced, and his education stopped at the seventh grade. The only job he ever knew was one in a sawmill. That may be too strenuous for him.

Testing his talents and preferences, the vocational experts found the young man liked assembling electrical equipment. He is deft at it and finds it interesting.

The doctors reported that he would do best in a job at a bench. The experts observed that this could be solved with a job in a factory making electrical equipment. He is rehearsing for it now, will leave the hospital a semi-skilled worker.

Red Cross worker gives Wood-carving instruction in a U. S. naval hospital in New Zealand. (Official U. S. Marine Corps Photograph)

In naval hospitals today patients work in their beds with such things as automobile fuel pumps, carburetors, and electric motors, having converted their beds into workshops. They are taking what is called “concentrated short work experiences."

Those are samples of various jobs, so that a man may grow familiar with the tools and processes involved and the theoretical information that goes with them.

This enables him to determine whether he has enough real interest in the work to adopt it as a career. If he has, the educational services officers make sure he learns all he can about his interests before he leaves the hospital.

The hospitals themselves do double duty; patients learn new trades or brush up on old ones in the hospital carpentry shop, the garage, and sometimes the office. Patients in some localities have access to the facilities of local trade schools, with the Red Cross transporting them from hospital to school.

Other patients attend college or high school while recuperating. An experiment is being conducted in which men train for specific jobs, in a particular factory, while still in the hospital. Developing skill sometimes serves also as a corrective exercise.

Also on duty in the hospitals are officers trained in civil readjustment. They advise men on the rights and benefits of veterans, help them over the hurdles of discharge and bridge the gap between life in the service and life as a civilian.

Fulltime contact men from the Veterans Administration and the U. S. Employment Service also work right in the larger hospitals, smoothing the path for men who have questions about pensions or insurance and advising them on how and where to get jobs. In this way, the Navy can be sure its program contributes to the more significant role of the Veterans Administration.

A Marine fighter pilot bailed out of his burning plane and was attacked in mid-air by a Jap flier, whose propeller cut off the Marine's foot. He was fitted with a substitute permitting such dexterity that he is back on flight duty again.

Also back on flying duty, after a terrific battering, is a Navy pilot who was nursed back to health after falling 2,000 feet into the sea without a parachute. Those cases illustrate the often-amazing job of human repair work being done today.

Another Navy flyer, who lost both arms, has come through the rehabilitation program in such good shape that he is stepping into an excellent job as a meteorologist. He could do his typing and drive his car before he left the hospital.

Cases like his go far to prove the heartening fact that what always have been called “handicaps” are by no means the actual handicaps they used to be.

In the New York Navy Yard, three junior officers who in civilian life were successful personnel or production men made a study to see where disabled veterans would fit in. They found opportunities ranging from common laborer to a first-class mechanic, where a man's service training was utilized.

The result is that the New York Navy Yard now employs more than 1,400 discharged veterans, including many who have lost an arm, a leg or an eye. Skills these men learned in uniform translate easily into civilian jobs.

A Useful Life

No man is so handicapped, the Surgeon General has said, that he cannot become a useful citizen. So far as it is in the Navy's power, no disabled man will be returned to his community without being well equipped physically and psychologically.

Whatever has happened, the disabled man is taught that he still has a valuable place to fill in the world. The chaplains, who play a valued part in rehabilitation, do much to replace despair and bitterness with hope and a healthy, optimistic outlook.

In this counterattack on disability, encouraging victories are being won. There are very few men who have been blinded. In the Philadelphia Naval Hospital, where the blind ultimately are brought for training, there are not more than a score of these patients, including men blinded by the sort of mishaps common in civilian life.

They are trained to live a full and normal life, prepared to take up civilian status with assurance. Highly encouraging work also is being done with the deaf. If a man has lost an arm or leg, a plastic substitute precisely suited to his needs is made in the hospital by skilled craftsmen working in constant collaboration with the surgeons.

It is routine that these men learn to drive an automobile and dance. A great many are permitted to return to military duty. Others go into civilian life at trades learned while recuperating. Injuries like this are not to be spoken of lightly. However, the hardship can be reduced, and the rehabilitation program is proving it.

This war, like others, will inevitably leave its harvest of disabled men. However, the thorough program of early, continuous and individualized rehabilitation is contributing much to helping them find where they will fit.

"Reducing the Human Cost of War," in All Hands: Bureau of Naval Personnel Information Bulletin, Washington, DC: Bureau of Naval Personnel, NAVPERS-0, No. 354, January 1945.

Note: We have edited this text to correct grammatical errors and improve word choice to clarify the article for today’s readers. Changes made are typically minor, and we often left passive text “as is.” Those who need to quote the article directly should verify any changes by reviewing the original material.