Recovery of the Head Tax

Explanation for the Recovery of the US Head Tax from the Cunard Line, 1931. | GGA Image ID # 2327467d84

🧾 Recovery of the U.S. Head Tax

💡 What Was the Head Tax?

From 1882 until the 1950s, the United States government required most arriving passengers to pay a Head Tax (by the 1920s–30s, $8 per person). It was intended to fund immigration processing, though in practice it often became an added burden for short-term visitors, returning U.S. citizens, and transatlantic business travelers.

Steamship companies collected the fee in advance, adding it to the cost of an ocean ticket. Certain groups were exempt — such as U.S. citizens, children under 16 traveling with parents, and accredited diplomats.

🔄 Refunds (Recovery of the Head Tax)

Not every traveler had to permanently part with that $8. A refund system existed for those in “transit” through the United States:

Short-Term Visitors – Travelers leaving the U.S. within 60 days of arrival could apply for a refund.

Documentation Required – Passengers had to request and complete Form 514 (Transit Certificate) from immigration inspectors at their port of entry.

Steamship Purser’s Role – When departing, the certificate had to be endorsed by the ship’s purser with the vessel’s name and date of sailing.

Deadline – The completed form had to be filed with the U.S. Immigration Department within 120 days of arrival.

Rail Travelers – Those exiting the U.S. by train had to hand the certificate to the conductor for completion at the border station.

Refunds could be claimed either:

- Directly through the steamship company offices (e.g., Cunard, United American Lines, etc.), or

- Onboard the return voyage, processed by the Purser.

📜 Exceptions to the Head Tax

Passengers exempted from paying included:

- U.S. citizens with valid passports (or birth certificates).

- Children under 16 traveling with parents.

- Diplomats, consuls, and accredited officials of foreign governments.

- Some temporary residents with verified return tickets.

Women born abroad but married to U.S. citizens after September 21, 1922, were not automatically exempt and usually had to pay the tax.

🧭 Why It Matters for Researchers

For genealogists, mentions of the Head Tax or “Form 514” in a passenger list:

- Signal temporary vs. permanent migration.

- Reveal whether a traveler intended to stay in the U.S. or simply pass through.

- Provide clues about family travel plans and business connections.

For historians, the Head Tax illustrates how U.S. immigration policy sought to control short-term arrivals while extracting revenue from ocean travel.

📸 Archival Example

Explanation for the Recovery of the U.S. Head Tax from the Cunard Line, 1931.

GGA Image ID # 2327467d84

✅ Final Thoughts

The U.S. Head Tax was never just a bureaucratic formality — it affected millions of travelers and shaped how steamship companies documented voyages. Today, surviving refund instructions and receipts help researchers reconstruct how passengers navigated both the Atlantic and America’s immigration system.

📌 Genealogist Tip: Head Tax Refunds

Why it matters – If your ancestor’s passenger list mentions the Head Tax or Form 514, it’s a clue about whether they were immigrating permanently or just visiting.

Refund clue – A note about “refund” or “transit” often means the traveler planned to stay less than 60 days in the U.S.

Family connections – Many return travelers were visiting relatives or conducting business. Look for matching names in earlier or later passenger lists.

Extra paper trail – Completed Transit Certificates sometimes survive in U.S. or steamship company archives, offering another layer of documentation.

💡 Use Head Tax notations to separate long-term immigrants from short-term visitors — it can prevent false leads in your family tree.

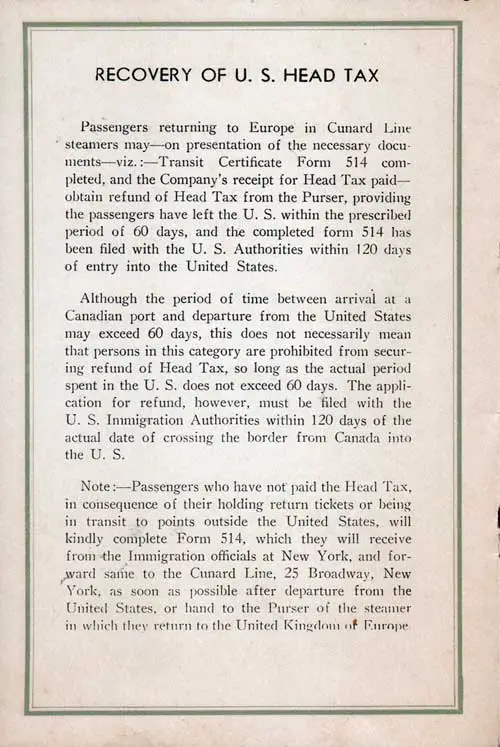

RECOVERY OF U. S. HEAD TAX

Full Text of Cunard's "Recovery of U. S. Head Tax" from the image above.

Passengers returning to Europe in Cunard Line steamers may—on presentation of the necessary documents—viz.:—Transit Certificate Form 514 completed, and the Company’s receipt for Head Tax paid— obtain refund of Head Tax from the Purser, providing the passengers have left the U. S. within the prescribed period of 60 days, and the completed form 514 has been filed with the U. S. Authorities within 120 days of entry into the United States.

Although the period of time between arrival at a Canadian port and departure from the United States may exceed 60 days, this does not necessarily mean that persons in this category are prohibited from securing refund of Head Tax, so long as the actual period spent in the U. S. does not exceed 60 days. The application for refund, however, must be filed with the U. S. Immigration Authorities within 120 days of the actual date of crossing the border from Canada into the U. S.

Note:—Passengers who have not paid the Head Tax, in consequence of their holding return tickets or being in transit to points outside the United States, will kindly complete Form 514, which they will receive from the Immigration officials at New York, and for- ward same to the Cunard Line, 25 Broadway, New York, as soon as possible after departure from the United States, or hand to the Purser of the steamer in which they return to the United Kingdom of Europe.

📚 Teacher & Student Resource

Many of our FAQ pages include essay prompts, classroom activities, and research guidance to help teachers and students use GG Archives materials in migration and maritime history studies. Whether you’re writing a paper, leading a class discussion, or tracing family history, these resources are designed to connect individual stories to the bigger picture of ocean travel (1880–1960).

✨ Educators: Feel free to adapt these prompts for assignments and lesson plans. ✨ Students: Use GG Archives as a primary source hub for essays, genealogy projects, and historical research.

📘 About the Passenger List FAQ Series (1880s–1960s)

This FAQ is part of a series exploring ocean travel, class distinctions, and the purpose of passenger lists between the 1880s and 1960s. These resources help teachers, students, genealogists, historians, and maritime enthusiasts place passenger lists into historical context.

- Why First & Second Class lists were produced as souvenirs.

- How class designations like Saloon, Tourist Third Cabin, and Steerage evolved.

- The difference between souvenir passenger lists and immigration manifests.

- How photographs, menus, and advertisements complement list research.

👉 Explore the full FAQ series to deepen your understanding of migration, tourism, and ocean liner culture. ⚓

📜 Research note: Some names and captions were typed from originals and may reflect period spellings or minor typographical variations. When searching, try alternate spellings and cross-check with related records. ⚓

Curator’s Note

For over 25 years, I've been dedicated to a unique mission: tracking down, curating, preserving, scanning, and transcribing historical materials. These materials, carefully researched, organized, and enriched with context, live on here at the GG Archives. Each passenger list isn't just posted — it's a testament to our commitment to helping you see the people and stories behind the names.

It hasn't always been easy. In the early years, I wasn't sure the site would survive, and I often paid the hosting bills out of my own pocket. But I never built this site for the money — I built it because I love history and believe it's worth preserving. It's a labor of love that I've dedicated myself to, and I'm committed to keeping it going.

If you've found something here that helped your research, sparked a family story, or just made you smile, I'd love to hear about it. Your experiences and stories are the real reward for me. And if you'd like to help keep this labor of love going, there's a "Contribute to the Website" link tucked away on our About page.

📜 History is worth keeping. Thanks for visiting and keeping it alive with me.