📜 Finding That Elusive Passenger List (FAQ)

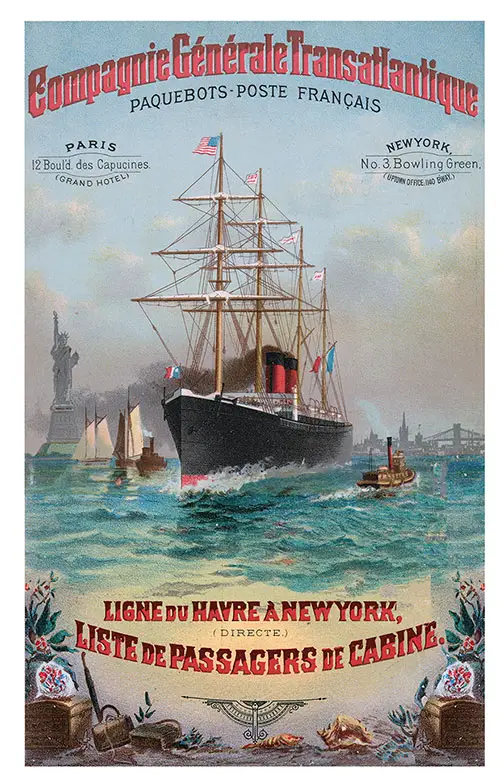

Example of a Souvenir Passenger List at the GG Archives French Line steamer SS La Bretagne, 5 February 1887 Voyage. | GGA Image ID # 2119899c0f

Why Passenger Lists Can Be Hard to Find ⚓

At the GG Archives, one of the most frequent questions we receive is: “How can I locate a passenger list for my ancestor?”

The answer often depends on timing, luck, and skill. Passenger lists served different purposes depending on class and destination. While governments required official manifests, steamship lines produced souvenir lists primarily for marketing and prestige. Understanding this distinction is crucial for genealogists and family historians.

The Passenger Manifest 📜

- Official government record — created at departure and verified at arrival.

- Where to find them:

- U.S. National Archives (NARA) microfilm

- Ancestry.com, Fold3, FamilySearch

- Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation

- Equivalent archives in Canada, Australia, and other destination countries.

- Annotations:

- Names crossed out = passenger didn’t sail, or upgraded/downgraded during the voyage.

- Steerage passengers upgrading to Second Class often appear in two places.

👉 Tip: Many manifests can be searched for free through public library subscriptions to Ancestry.

Souvenir Passenger Lists 🎟️

- Produced by the shipping companies for First and Second Class (later Tourist Class).

- Purpose: Marketing tools, meant to be kept as keepsakes by wealthier travelers.

- Where to find them today:

- eBay, Etsy, Amazon (vintage section)

- Maritime ephemera dealers

- Used bookstores (London, New York, and port cities)

- Estate sales and historical society donations

- Challenges: They are scarce, expensive, and incomplete. At GG Archives, only a fraction survive due to the enormous cost of acquisition.

⚠️ Note on Steerage: Few souvenir lists were printed for steerage passengers. Norddeutscher Lloyd was a rare exception. For most immigrant ancestors, manifests (not souvenir lists) are the only record.

Why Passenger Lists Were Printed 📰

Marketing value: Lines wanted elite passengers to keep lists as souvenirs and reminders to book again.

Press use: First- and Second-Class lists were often sent to New York newspapers, which reported on the “Who’s Who” of arrivals.

Limited scope: Working-class migrants were rarely considered repeat customers. Their journeys were often one-way.

NARA & USCIS Records (1820–1951)

- 1820–1892: Customs Lists

- 1892–1924: Immigration Lists (Ellis Island era)

- 1895–1924: Canadian land border crossings

- ca. 1905–1924: Mexican land border crossings

- 1924–1944: Visa Files (USCIS Genealogy Program)

- 1944–1951: A-Files (later some converted to C-Files)

- Since 1951: All immigrants documented in A-Files (FOIA requests for post-1951 arrivals).

Links to Shipping Company Archives 🔗

Cunard Line Archives (Liverpool University)

White Star Line Archives (via Cunard - See Liverpool University Link Above)

Why This FAQ Matters 📚

For genealogists: Clarifies why some ancestors appear in passenger lists and others don’t.

For historians: Explains the marketing and social dimensions of steamship travel.

For teachers & students: Provides a primary-source–based look at migration, marketing, and class distinctions in ocean travel.

For collectors: Offers practical tips on where to find surviving lists today.

🎓 Student Essay Prompt: Souvenir vs. Official Passenger Lists

Essay Topic

Passenger lists were not just travel records—they reflected class, migration, and marketing strategies. Souvenir passenger lists preserved the journeys of wealthier travelers, while official manifests recorded the masses of migrants. What does this tell us about the social and economic realities of ocean travel between 1880 and 1960?

Guiding Questions

- Purpose & Audience – Why did steamship companies primarily produce souvenir lists for First and Second Class passengers? What does this suggest about their target customers and marketing strategies?

- Exclusion & Class – Why were steerage and many Third Class passengers rarely included in souvenir lists? What does this reveal about perceptions of immigrants during this era?

- Comparison of Sources – How do souvenir passenger lists differ from official government manifests (Ellis Island, Castle Garden, etc.)? Which is more useful for genealogical research, and why?

- Historical Context – How did changing U.S. immigration laws (such as the 1921 & 1924 quota acts) and the decline of steerage affect the types of lists produced?

- Research & Legacy – Why are passenger lists valuable today for genealogists, historians, and students? How do they help us connect individual family stories to broader migration history?

Writing Instructions

- Use examples from the GG Archives materials, especially passenger lists and FAQs, to support your arguments.

- Aim for 3–5 pages (double-spaced) with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Consider including at least one case study (e.g., a notable voyage, a specific immigrant family, or a famous passenger).

- Reflect on how the survival of some lists (but not others) shapes our view of history.

📚 Teacher’s Guide: Finding That Elusive Passenger List (1880–1960)

Learning Objectives

- Understand the differences between souvenir passenger lists and government immigration manifests.

- Explore how social class, marketing, and immigration policy shaped what records were produced and preserved.

- Develop research skills by evaluating primary sources for genealogy and historical study.

- Connect individual migration stories to broader global migration trends.

Key Discussion Points

- Souvenir Lists as Marketing Tools: Printed mainly for First and Second Class passengers—why?

- Steerage Exclusion: How class and one-way migration patterns shaped recordkeeping.

- Government Manifests: Their completeness and utility vs. the prestige-driven souvenir lists.

- Historical Context: Effects of U.S. immigration laws (1921 & 1924 quotas), post-WWI migration shifts, and the decline of mass steerage travel.

- Research Challenges: Why finding a specific passenger list is often about “timing, luck, and skill.”

Suggested Classroom Activities

- Document Comparison: Provide students with a sample GG Archives souvenir list and an Ellis Island manifest page. Ask them to note differences in detail, purpose, and intended audience.

- Class Debate: “Which record type is more valuable for historians—souvenir lists or government manifests?”

- Role-Play Exercise: Students assume roles of different passengers (First Class tourist vs. steerage immigrant) and explain why their names may or may not appear in a souvenir list.

- Digital Scavenger Hunt: Assign students to locate a specific voyage or ship in GG Archives and report what class of passengers are included.

Essay Prompt Connection

- Encourage students to use the essay topic “Souvenir vs. Official Passenger Lists: What They Reveal About Migration and Class (1880–1960)” as a capstone project.

- Provide guiding questions (already listed in the student prompt) to help them focus.

Extensions

- Family History Project: Students interview relatives or use genealogical sites to see if they can find passenger list references to their own ancestors.

- Cross-Curricular Tie-In: Connect to literature (e.g., immigrant novels), economics (cost of passage), and sociology (class divisions).

How to Locate a Passenger Manifest at NARA

The official arrival record of immigrants who arrived before July 1, 1924, is a passenger list or manifest. Ship passenger lists for those who arrived 1820-1892 (Customs Lists) or 1892-1924 (Immigration Lists), as well as land border manifests for arrivals from Canada 1895-1924 and Mexico ca. 1905-1924, are available on microfilm at the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) or online subscription sites such as Ancestry, Statue of Liberty Organization, and others.

Visa Files, the official arrival record of immigrants admitted for permanent residence between July 1, 1924, and March 31, 1944, are available through the USCIS Genealogy Program. Many Visa Files were later moved to become part of an A-File or C-File after 1944.

All immigrants admitted for permanent residence who arrived between March 31, 1944, and May 1, 1951, were initially documented in A-Files, a unified folder intended to hold all records related to one individual. If the immigrant naturalized before April 1, 1956, their A-File was converted to a C-File. A-Files numbered below 8 million (arrived before May 1, 1951) and C-Files 1906-1956 are available through the USCIS Genealogy Program.

All immigrants admitted since May 1, 1951, should be entirely documented in an A-File, a unified folder to hold all records related to one individual. A-Files numbered 8 million and above (arrived May 1, 1951 and after) are available through the USCIS Freedom of Information Act and Privacy Act Program.

Links to some of the Shipping Company Archives

- Cunard Line: https://libguides.liverpool.ac.uk/library/sca/cunardarchive

- French Line: https://www.frenchlines.com/archives/

- White Star Line: See Cunard Line Archives

- Holland-America Line: https://www.hollandamerica.com/blog/recent-articles/whats-new/explore-passenger-lists-from-early-1900s/

Last Updated February 2024.

📚 Teacher & Student Resource

Many of our FAQ pages include essay prompts, classroom activities, and research guidance to help teachers and students use GG Archives materials in migration and maritime history studies. Whether you’re writing a paper, leading a class discussion, or tracing family history, these resources are designed to connect individual stories to the bigger picture of ocean travel (1880–1960).

✨ Educators: Feel free to adapt these prompts for assignments and lesson plans. ✨ Students: Use GG Archives as a primary source hub for essays, genealogy projects, and historical research.

📘 About the Passenger List FAQ Series (1880s–1960s)

This FAQ is part of a series exploring ocean travel, class distinctions, and the purpose of passenger lists between the 1880s and 1960s. These resources help teachers, students, genealogists, historians, and maritime enthusiasts place passenger lists into historical context.

- Why First & Second Class lists were produced as souvenirs.

- How class designations like Saloon, Tourist Third Cabin, and Steerage evolved.

- The difference between souvenir passenger lists and immigration manifests.

- How photographs, menus, and advertisements complement list research.

👉 Explore the full FAQ series to deepen your understanding of migration, tourism, and ocean liner culture. ⚓

📜 Research note: Some names and captions were typed from originals and may reflect period spellings or minor typographical variations. When searching, try alternate spellings and cross-check with related records. ⚓

Curator’s Note

For over 25 years, I've been dedicated to a unique mission: tracking down, curating, preserving, scanning, and transcribing historical materials. These materials, carefully researched, organized, and enriched with context, live on here at the GG Archives. Each passenger list isn't just posted — it's a testament to our commitment to helping you see the people and stories behind the names.

It hasn't always been easy. In the early years, I wasn't sure the site would survive, and I often paid the hosting bills out of my own pocket. But I never built this site for the money — I built it because I love history and believe it's worth preserving. It's a labor of love that I've dedicated myself to, and I'm committed to keeping it going.

If you've found something here that helped your research, sparked a family story, or just made you smile, I'd love to hear about it. Your experiences and stories are the real reward for me. And if you'd like to help keep this labor of love going, there's a "Contribute to the Website" link tucked away on our About page.

📜 History is worth keeping. Thanks for visiting and keeping it alive with me.