The Peasant Costumes of Europe circa 1900

In the faces and costumes of the people are written the history of a nation, the record of its degeneration and its development-the men of the cities become uniform, cosmopolitan; the folk of the farms and the mountains remain types, standards of racial characteristics.

The constant interchange of visits between members of different nationalities brought about by the improvement in the means of travel; has done much to wipe out racial characteristics.

The nineteenth century saw a more significant advance in uniformity of dress, of the manner of language, and of innovation than had ages before.

A peasant woman of the Austrian Tyrol.

The modern man of Berlin is scarcely discernible from the gentleman of London, and the educated citizen of St. Petersburg is with difficulty; distinguishable from the inhabitant of New York.

These are the capitals of the great traveling nations, and their Peoples have approximated more closely to a common type than have the dwellers in the Latin cities—Rome, Paris, and Madrid.

If one sits in any of the world's great congregating places—in Shepheard's Hotel in Cairo, in the Carlton in London, in the casino at Monte Carlo, in the Opera in Paris, in the Waldorf Astoria in New York—he will see around him members of a dozen nationalities alike in figure, dress, and deportment, cosmopolitans.

A hundred years ago it was vastly different; the Italian marquis at a glance was separated from the English milord, the German baron had nothing in common with the American Democrat or the French republican. The Russian noble and the Spanish grandee were wide as the poles asunder.

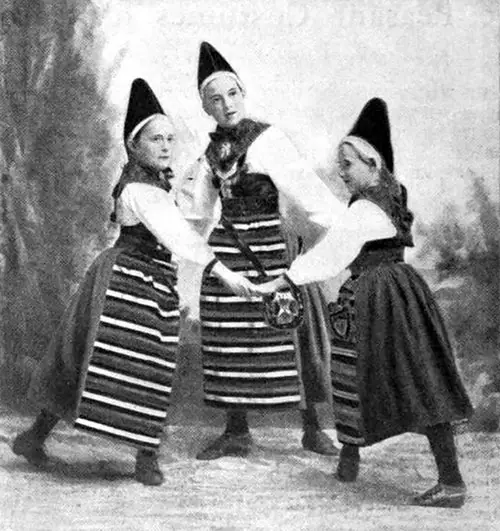

Three Children Of The Old Swedish Province Of Dalecarlia.

From a photograph by Florman, Stockholm

The people unmistakably bore the stamp of their nation of origin. Today their language alone distinguishes them, and that is rapidly ceasing to be a reliable means of demarcation.

Where the Old Types Survive

In the cities, one can no longer find types and standards. They are relegated to the country districts, to the homes of the peasantry, to the tracts devoted to agriculture, vine culture, fishing, and hunting, to hereditary employments.

There one finds models of the original Frenchman, the Scotsman of the Lowlands, the Irishman of the bogs, the Italian of the olive groves, the Greek of Sparta and Corinth. Their old customs are reverenced, ancient traditions are retold; national costumes are retained.

Every parish of Brittany and Normandy has its distinctive headdress, every parish calling its special costume. For untold generations, these have descended front mother to daughter in exact facsimile, the gala garments without alteration, the ornaments as heirlooms.

In these peasant costumes are written the histories of Europe, the successive supremacies of Gauls and Teutons, Romans and Moors, Spanish and French and English.

Down in southeastern Europe, the classic features of the Greek have been sensualized by the Turk.

In Transylvania, the people of the fields have been brutalized by the Mongolian.

In modern Alsace Lorraine, the peasants have been molded by other French and German conquests into a race that is neither French nor German. Are all of these things written in the dress of the ordinary people, stamped upon their features?

A Belgian Peasant Woman At The Spinning Wheel

In Scandinavia, partly from its inaccessible position, partly from the anchorage of its mountains, the people have retained in almost their pristine purity the garb and habits of the Norsemen.

In Finland, the peasant dresses hear the marks of various influences of the original Finns, of the Mongolians, of Swedes and Germans and Lapps, most recently and most potently of the Russians.

Holland, although the battleground of the Spaniards and the Germans, the Danes, and the French, has yielded little to any in its choice of national and local habiliments.

The Dutch are a stubborn people, and in their thick wooden shoes, their multiplicity of petticoats and trousers, their carefully laundered kappies, they have retained a characteristic that no foreign influence has been able to modify.

In southeastern Europe, conditions are otherwise. The peoples have proved more pliable, more tractable.

A Bulgarian Peasant Girl

From a photograph by the Berlin Photographic Company after the painting by K. Dielite.

The Peasants of Greece

A modern Greek was asked one day why the women of Greece are not more beautiful. He replied. " You must remember that the Turk has passed this way.''

During the three hundred years and more of Turkish rule, the most beautiful women in the land were taken for the Turkish harems, and in the short period that has elapsed since the independence of Greece, the nation has not been able to replace the loss. Moreover, beautiful women are still found in Greece.

It could not be otherwise, for as the beauty of the ancient Greeks harmonized with the rare colors of sea and sky, the graceful outlines of rolling mountains, and the fineness and purity of the atmosphere, so also the modern types correspond in a certain degree to their environment.

A Young Man From One Of The Greek Islands, Where The Old Hellenic Type Is Fount At Its Purest.

Except for the court dress, women in Athens at present follow European fashions. However, there is a national costume to be found not only in the provinces but in Athens itself.

This national costume assumes different forms in different places. However, it always has one common characteristic—the front of the dress, and often the head and arms, are covered with heavy ornaments of coins and jewelry, heirlooms in the family, representing the dowry of one bride after another, perhaps for many generations.

Barbarians in Hellas

In marked contrast to the Greek type, there are in the near vicinity of Athens women of very different national characteristics. Eleusis, even, so intimately connected with the history of Athens, is mainly inhabited at present by Albanians.

One drives out to Eleusis over the old sacred way, through the ancient groves of olives, over the path where the processions of a dead past wounded their solemn course: but Eleusis, where Demeter herself founded the mysteries, and where Eschylus was born, contains but few Greeks.

A Norwegian Bride Dressed For Her Wedding Festival

The Easter dances of the Albanians replace the grand torchlight processions of the Greeks. Girls join hands in a long line and advance in a sort of interrupted procession, retiring and changing hands after every fourth step, and then advancing again.

The music sung by the dancers is a monotonous chant themselves, and such gaiety as the dance provides comes from the brilliance of the costumes. Otherwise, it would be decidedly solemn.

Peasant Girls Of Lorraine (seated) And Of Alsace (standing) In The Traditional Costumes Of Their Provinces

Not only are there Albanians in Eleusis, two hours' drive from Athens, but another different race is largely represented in the near vicinity of the city.

In its environs are many Wallachians, the remnants of the old Wallachian kingdom which once embraced Aetolia, Acarnania, and Thessaly, the "Great Wallachia" of medieval writers.

Thus the foreign inhabitants of Greece crowd up even to the gates of Athens, and her citizens no longer represent a true Greek type. The old Greek type is well in its beauty and its purity among the servant girls who go in large numbers from the Greek islands to Constantinople and the cities of the east.

The Daughters of Laced Æmon

In contrast to the maidens of Athens are the daughters of Sparta. From the range of low hills, one gazes out over the beautiful plain which forms the valley of the Eurotas, surrounded on every hand by lofty ramparts of mountains.

Here were developed the brave men and women who made Sparta a name for endurance, the mothers who begged their sons not to return from the battle unless victorious.

The modern Spartan woman shows something of this inheritance in her face and would not be unworthy to walk in the ancient Spartan procession to the Menelaion, where the men implored Menelaus to grant them courage and success in war, and the women prayed to Helen to bestow beauty on themselves and their children.

The twentieth century Spartan wanders in gardens abounding in orange trees—the modern gardens of the Hesperides.

In the warm evening air, the men take their ease in a picturesque tavern under an enormous spreading tree near the city; the children play in the green lanes, the Spartan maidens fill their pitchers at a spring that gurgles from an old wall.

In the distance, the snow-clad Taygetus, with the sunset sky above it, forms a picture of Arcadia. There is no city in Greece with so beautiful a location like Sparta. There are no Greek maidens whose eyes reveal so much soul as those of the Spartans.

A Peasant Woman Of Bosnia In Gala Costume.

From a Photograph by the Detroit Photographic Company

On the Corinthian Isthmus

Ancient Corinth was celebrated for luxury and splendor, rather than for learning and art or Spartan courage, and the racial inheritance is very different from that of the Athenian or Spartan Greeks.

The woman of Corinth is beautiful, but not with the calm beauty of the Greek; it is the spiritual type of the Italian or the French.

The natural beauty of Megara is not so fairy-like as that of Corinth, where the delicacy of the tints of sky and sea is the principal characteristic, but the coloring of the plain and town of Megara is more decided and less elusive, consequently less beautiful.

In Corinth, the colors of the sunset, azure, lilac, and rose steal upon the senses, but in Megara, one thinks less of the beauty of the evening, more of the Asian appearance of the town.

Megara is built of snow white homes rising one above the other, each having a low doorway opening into a court, shaded here and there by a fig tree.

The shining white stone used in the architecture of Megara is the same now as it was in the time of Pausanias. When Plato fled to Megara after the death of Socrates, it was in a white house similar to one of these that he was sheltered.

The dazzling white walls and the brilliant sunshine make an excellent background for the gay costumes of the women, the bright colors of which, red, green, blue, and yellow, give the eastern effect to the scene.

In the Mountains of Greece

From the Asian beauty of southern Greece, one climbs to the region of Parnassus. On its slopes are flocks of sheep watched by shepherdesses who are brave and sturdy, but not beautiful.

Even the sheep on Parnassus become hardened, and sharpen their noses between the rocks, seeking the pale, thin grass. Nothing is heard on the mountainside but the jingling of mule bells, the bells of the leaders of the flocks, the cries of the muleteers and the shepherds.

The sun disappears early behind the high mountain slopes, the gloom of the evening begins long before the young girls watching their sheep there can go to their dreary homes.

It is a hard and monotonous life last develops a sturdy race of people so that the peasants from Parnassus stand for courage and endurance. The best among the men are chosen for the king's guard in Athens, where their picturesque costume adds to the interest of the street life.

The Daughters Of The Dykes—two Dutch Peasant Girls In Characteristic Costumes.

From a Photograph by the Detroit Photographic Company.

Farther away from Greek centers, in Macedonia and Thessaly, are few pieces of evidence of the Greek type. The intermixture of various races, lack of the inspiration that good schools give, have led to the degeneration of form, to stolidity of character.

In the faces of these distant provinces, it is apparent only the germ of the spirit of ancient Greece is evident after centuries of bondage to the dreaded and hated Turk.

A Girl Of The Greek Mountains -- A Shepherdess Of Parnassus In Her Holiday Dress.

Greece has regained her independence, but she can never be anything but an impoverished little state of no political importance or military power. The marvelous tire of her classic genius is quenched, her old leadership in art and literature is lost forever.

However, in no corner of Europe do the faces and costumes of the peasantry suggest such historical memories as in the land of Pericles and Leonidas.

Day, W. Freeman, "The Peasant Costumes of Europe," in Muncy's Magazine, New York, The Frank A. Munsey Company, Volume XXVIII, Number 2, October 1902, p. 231-240.

Note: We have edited this text to correct grammatical errors and improve word choice to clarify the article for today’s readers. Changes made are typically minor, and we often left passive text “as is.” Those who need to quote the article directly should verify any changes by reviewing the original material.

Vintage Folk Costumes

GG Archives

Vintage Folk Costumes (Bunads)

- Folk Costumes from Dalarna, Sweden

- Folk Costumes - Liebig's Extract Trade Cards

- Peasant Costumes of Europe

Vintage Fashion Topics

Updates and Social Media

- Visit our GG Archives Vintage Fashions Facebook Page for the Latest News About the Activities of the Archives.