What Are Liqueurs?

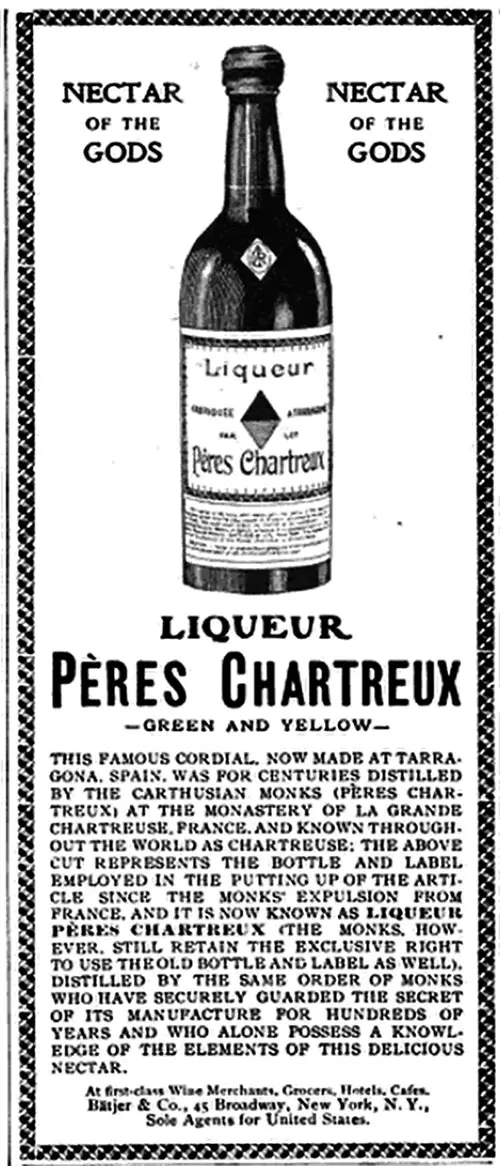

Pères Chartreux - Green and Yellow Liquor © 1907

Though the taking of a "liqueur" after dinner may not be a pressing necessity, yet it is probably a physiologically correct proceeding apart from the question of the wholesomeness of the individual constituents of the sweet aromatic spirituous liquid.

Liqueurs are, of course, decidedly stimulating, and they induce a sense of warmth and comfort after a meal which may mask any feeling of gastric discomfort that might otherwise be experienced.

This effect, however, says the Lancet, is due to some extent to the spirit, but more particularly it may be referred to the aromatic oils. The oils of aniseed, absinthe (wormwood), cinnamon, caraway, etc., and most other aromatic oils are carminative and soothing, and therapeutically these come under the general description of stomachic.

The liqueur is not necessarily a product of distillation so far as its aromatic ingredients are concerned. The distilled products, however, are probably preferable to a little spirituous infusion from the dietetic point of view.

Chartreuse and Benedictine are distilled from a mixture of various natural aromatic substances, many of which, it is said, are contained in the British Pharmacopoeia.

Kummel, again, is distilled from caraway seeds, and many authorities consider that this liqueur is the most wholesome. The coloring matters used in liqueurs are, of course, added, amongst the substances used being Prussian blue, sulfate of indigo, burnt sugar, spinach, or parsley green, cochineal, logwood, saffron, turmeric.

Chloroform, it is said, is often a constituent of liqueurs, and internally chloroform has a marked sedative action on the stomach and is an antispasmodic.

Amongst other components used in the formulae of cocktails obtained by simple infusion are aloes, a spirit of nitrous ether, acetic ether, and ammonia.

It is not to be supposed that the best ingredients are necessarily added since any imperfections would not be evident to the palate on account of the robust nature of the aromatic oils.

Certainly celebrated liqueurs have, as is well known, an exciting and classic history, and the secrets of their manufacture are still most jealously guarded. Doubtless, these liqueurs had their origin in the fact that their main effects was that of a carminative during digestion owing to the aromatic oils.

La Chartreuse

Pères Chartreux Green and Yellow Liqueur © 1905

Of all the ancient liquors of France the best known is assuredly that to which the disciples of Saint Bruno have given their name and which belongs to the mother-house, La Grande Chartreuse, in Dauphiné.

This elixir was at first a simple potion prescribed by the physician Bronault, with the quality, exceptional at that time, of extracting the essential oil of drugs by means of alcohol; mint, cinnamon bark, and cloves were and are still used, but today forty plants lend their flavor to the compound.

The reputation of this liqueur was dawning when the Revolution dispersed the monks and confiscated the convent. When, at the close of the Empire, the Chartreuse were permitted, on payment of a rental of one franc per year (which they still pay), to resume possession of their clerical edifices, a young monk, instructed by the elders who possessed the secret, manufactured once more the white Chartreuse, and gradually invented the yellow and the green.

He was called Dom Garnier, and the bottles still bear his name. To devote himself thus to a worldly pursuit all the more absorbing because of the increasing demand for his product, was a sore trial to this holy man, who had expected to free himself from the world by entering the most rigorous of all the orders.

Old age overtook him before his superiors permitted him to retire into another house of the order and spend the rest of his days exclusively in prayer. A friend relates to me that being permitted one day to visit this house, while he was conversing with the Prior, an old man with a very long beard, and still erect under his white robes, approached and by signs asked permission to speak.

Receiving permission, he begged to go for a pair of scissors on account of a nail which he had breken in working, and which gave him pain. “It is unnecessary,” dryly replied the Prior, and as the old man retired without a word, he said to his visitor with a smile : “You seem surprised at my harshness, but I am sure that our brother thanks me in his heart for having imposed this slight mortification upon him in the presence of a third party.”

The monk thus treated was Dom Garnier, whose skill had endowed the community with enormous sums. The Abbé of the Grande Chartreuse is one of three Chartreuse monks possessed of the secret of fabrication.

The commercial and technical management of the production is in charge of a monk assisted by twelve probationers. Between the two contrasting institutions, the monastery clinging to the snow-clad mountain side, where a handful of men live afar from the world, seeking in solitude to approach the Most High—and the fevered, vulgar manufactory, established in a village on the plain, to supply the eminently temporal need of poor human creatures eager to crown a copious repast with “a little glass,” there is no other bond. All the rest of the establishment is composed of lay workmen.

Most of the ingredients of the famous elixir are known; the receipt is very simple. The quality of La Chartreuse results from the great purity of the wine brandy used, and the freshness of the herbs gathered in the vicinity by the mountaineers.

The same results could not be obtained with dried herbs. The pickers who sell their daily gathering to the works know the favorite haunt of each wild flower, whether along abrupt slopes or, like certain ferns, at the water's side, near fountains and in abandoned pits.

La Bénédictine

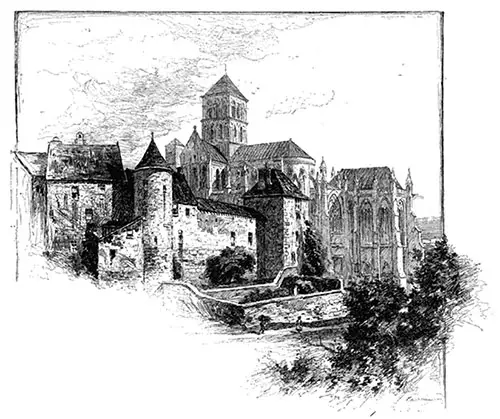

The Burned Benedictine Abbey at Fécamp, France © 1892 The Illustrated American

This rival liqueur, which the English have christened “Dom,” the Russians, “Monachorum,” and the Swedes, “Munck Licor,” was launched in 1863, by M. A. Le Grand, a wine merchant in Fécamp, who advertised it audaciously, to the amount of 800,000 francs, his entire fortune.

Results were at first modest, but the demand increased steadily; by 1889 it reached the figure of 664,000 bottles, and during the last nine years this figure has nearly doubled; the annual sale exceeds 1,100,000 of the dumpy bottles whose complicated ornamentation, leaden and many colored seals, have not been without influence upon this success.

The net profit of one franc per bottle is less than that of La Grande Chartreuse, because the expenses are greater. The French public absorbs 500,000 francs yearly, but two-thirds of La Bénédictine are exported.

The secret of the fabrication is trivial; that it was consigned by a Benedictine monk to a manuscript in 1510, and opportunely discovered by M. Le Grand in 1863 is perhaps a fairy tale.

Whether he had or had not a manuscript, whether it came authentically or not from the library of the Benedictines at Fécamp, is of little importance to the wine drinkers of 1898. Certainly M. Le Grand had to fight hard for his appellation of “Bénédictine.”

The clergy protested against the unceremonious appropriation of the name of an Abbey illustrious until destroyed by the Revolution, and Cardinal Bonnechase petitioned Napoleon III. to put an end to the scandal.

Nevertheless, M. Le Grand, who died a year ago, was profoundly religious, and if La Chartreuse is a convent that created a liquor, La Bénédictine is a liquor that has restored a convent—or very nearly so.

Attached to the manufactory, which is surmounted by a Gothic steeple resembling that of a church, with bottling rooms whose pointed arches suggest devotion, there is an interesting archaeological museum where the founder collected a quantity of ecclesiastical relics of the Middle Ages— founts, missals, reliquaries, sacred jewelry, statues, sacerdotal fabrics—in all filling a catalogue of two hundred pages.

The management desired to have regular Benedictines of flesh and blood, whom it would lodge, board and provide with a small salary and a slight interest in the profits.

A contract to this effect with the Abbaye de Saint-Wandrille has not yet been carried out, but the diocesan authority has recovered from its early prejudices.

The present Archbishop of Rouen came to bless the most recent constructions, among which is a superb Salle des Abbés, and at the banquet following the ceremony, during the dessert, he compared the honorable M. Le Grand to several of the heroes of Christianity.

"Liqueurs," in The Epicure: A Journal of Taste, Vol. VIII, No. 95, October 1901, p. 344+

"A Department of French Letters: La Chartreuse and La Bénédictine", in Current Literature: A Magazine of Record and Review, Vol. XXV, No. 3, March 1899, p. 227+.