A Romance in Champagne - 1894

VITICULTURE is one of the chief industries pursued in France. In 1893, the total yield of wine in the seventy-six departments of France was 1,125,000,000 gallons, or nearly twice the quantity given in the vintage of the previous year and the average annual yield for fifteen years past, the increase being general over all the vineyards of the country.

Preparation for Pole-Stacking

All pure champagnes come from the vineyards of Rheims, Epernay, and Châlons; are either "sparkling," "half-sparkling," or "still," and are all but colorless. The terms "partridge-eye," "amber," "pink," and "rose-tinted " denote that the manufacturer has so tinted his wines by adding to them an extract drawn from the pellicle of over-ripe grapes, or an extract from elderberries.

Uprooting the Vines

A great expanse of country in the arrondissements of Rheims, Epernay, and Châlons is devoted to viticulture for the special production of champagne; and the vineyards of Dizy, Bouzy, Verzenay, Mareiul, Hautvilliers, Ay, Epernay, and Muilly are widely celebrated for the splendor of their fruit.

Vine Staking

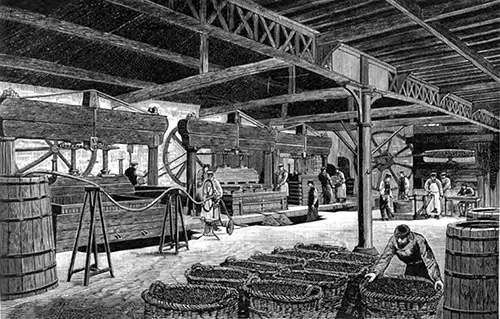

The finest champagne is produced by the juice from the black and the white grapes being mixed together — the black giving body and strength, the white delicacy and richness. In blending, more juice from the black grape is used than from the white; and in gathering the grapes, great care is taken that every grape is fully ripe before it is put into the press.

The Planting

Generally, the subsoil of the vineyards is chalky, and into this none but the finest varieties of the vine are planted, such as le Pineau, le Pineau gris, le Vert dore, and le Plant gris for black grapes,—and l'Epinette, le Pineau blanc, la Camal, and le Meslier for white.

In the champagne districts, from the vines planted on the slopes of the hills, especially from those that are planted up to about two-thirds of their height, the choicest and most equal-quality wines are produced.

Viticulture demands constant labor throughout the year. The preparation of the soil, the trimming of the plants, the removal and replacing of the poles, the watchful outlook for insects injurious to both plant and fruit, and "provining," or placing new branches from the plants in vacant spaces with their extremities rising out of the earth, give full and continuous employment to large numbers of the peasantry.

“Provining”

In October, immediately after the vintage, the poles are removed from the vines; the ground is weeded in November, and in this month and through December old stalks are removed, new vines are planted, and new shoots are layered in the vacant spaces.

In January and February, the first pruning is made; and this is one of the most important operations in the vineyard, as upon it alone the success of the vintage often depends.

Usually the pruner leaves on the stock two branches only, termed broches or pousses, and naturally the strongest shoots are left. In the young wood of black grape vines three buds are left to each shoot; in the white, one shoot only with four buds is left.

Vine Pruning

The vine is pruned above the third bud or "eye" of each shoot, and care is taken to ensure that the cut itself shall not incline towards the bud, lest the sap in rising should descend upon the bud and cause it to rot.

Digging and hoeing follow in March and April; in May, "provining" is again done where necessary, and a pole is fixed to every vine in the vineyard; the second weeding and second pruning are made in June, and the vines are tied to the poles by strawbands.

In July, the third weeding and third hoeing take place; in August, generally the vineyards are not interfered with, but every preparation is made for the coming vintage; in September, a final but slight pruning is done where requisite, and from the middle of the month to the first or second week in October, the vintage is in full activity.

Vine Clipper

When weeding and pruning, the vine-dressers make diligent search for all insects inimical to vine life. When the fruit changes color the attacks of the grape-worm are anxiously guarded against, as this worm not only injures the plant, but should any number be pressed with the grapes, the flavor of the wine would be injuriously affected, and its color slightly changed.

Vine Training

All labor in the vineyards is hand-labor. In the vintage, the bunches of grapes are cut from the vine; bad, green, and imperfect fruit is cut away by the experts; they place the finest bunches in baskets, to be taken to the presses in spring-carts, or on the backs of led horses, so that the fruit shall not be injured from jolting on the road.

Once begun, the vintage must be finished as quickly as possible. In gathering, the pickers are strictly forbidden to eat the grapes, and this not on account of the quantity so consumed, but because the perfume of the fruit, in picking, produces sufficient excitation without adding thereto by eating the grape itself.

Each basket of grapes is weighed, labelled with the weight and the name of vineyard where grown, and is then emptied into the press in the proportion of 4200 kilos, of black to 4000 kilos, of white; and this quantity of grapes will yield 2000 litres of wine-juice; this is subsequently drawn off into tuns holding a thousand gallons each.

The Wine Press

The absolute unification of all champagne wine-juice obtained from the different vineyards belonging to each respective house must be made, in order that all the wine shall be homogeneous and equal in quality for the year in which produced.

By fermentation the wine-juice, or "must," is changed into acidulous alcoholic liquid, or "wine." When the "cottee" has risen to the surface in the vat, and the sediment is deposited, the wine is racked into casks holding 200 litres.

These are placed in the underground cellars with a vine-leaf over each bunghole; upon this vine-leaf fine sand is sprinkled, and through the aperture thus made the carbonic-acid gas generated by fermentation escapes.

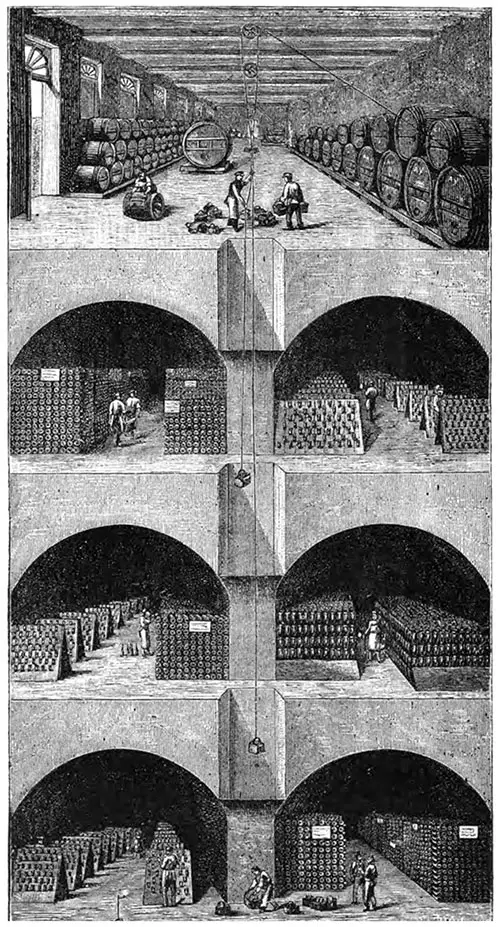

The Wine Cellars

In the spring, the casks are emptied into great tuns holding from 5000 to 6000 gallons each, preparatory to the final blending carried out under the direct supervision of the chiefs of the houses concerned.

The results of all tests made in the process of manufacture, the names of the vineyards whence obtained, and the quantities of each wine used in the whole, are placed before them.

They then make a final test, to ascertain what may be still needed to bring the wine fully up to the standard of excellence required by the house. In this final blending the chief aim is to make the whole of the wine absolutely homogeneous in tone, strength, and aroma.

After the final blending the wine is racked into 44-gallon casks, and these are again placed in the cellars, where they lie undisturbed till May, when bottling commences; the bottles are placed in iron bins in the deep underground cellars, and here the wine lies maturing for from two to three years.

Sectional View of a Portion of the Caves in the Rue St. Hilaire. (Champagne Périnet & Fils, Reims) © 1882 A History of Champagne

In its matured, effervescent state, when the carbonic acid is dissolved, the glucose decomposed, and the alcohol disengaged, a deposit remains in the bottle which must be removed without injury to the wine.

For this purpose, each bottle is placed obliquely in the side of a two-sided plane, each side holding about sixty bottles; or perpendicularly in a hole in a table, with the cork downwards.

To each bottle, day by day, the remueur or mover of the bottles gives a "scientific" rotatory movement, jerking it so as to loosen the sediment or "crust" from the sides, so that it may be deposited upon the cork. This operation is continued for months together, until the whole sediment has been thus deposited.

This method for "clearing the crust" from champagne was discovered by Madame Clicquot-Ponsardin, for many years the head of the house of Messrs. Clicquot & Co., of Rheims.

"Disgorging" (i.e., ejecting the sediment from the bottle) is effected by the disgorger holding the bottle, still head downwards, in his left hand, and with his right cutting the string that confines the cork.

The effervescing power of the wine drives out both cork and sediment, and then the disgorger speedily lifts the head of the bottle and takes care that no more wine is expelled than is absolutely necessary.

As, in the process of maturing, the original sweetness of the wine has disappeared, its loss must be replaced ; but this must be done in varying degrees, so as to adapt the wine to the tastes of the specific countries for which it is destined.

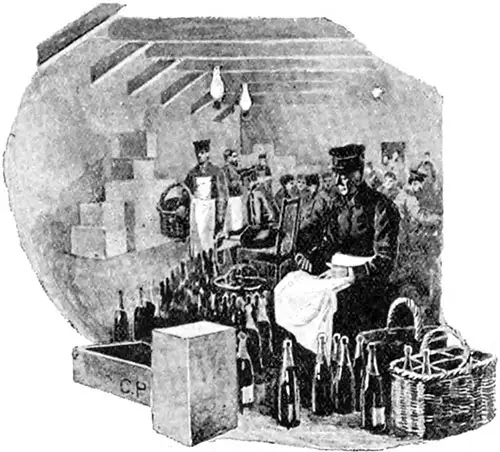

Preparing for Packing

By a machine each disgorged bottle is "dosed" automatically with an adequate quantity of "dosage," this dosage being made from cane sugar and alcohol.

Every cork used is new, is branded with the name of the house as a guarantee of its quality, and is secured by string, previously saturated with linseed-oil, and by twisted wire. To test the security of the corkage, the bottles lie in the cellars for six weeks before they are packed for delivery.

The exquisite flavor of the wine would disappear if the corks were not of the finest quality—hence these must be free from imperfections and must be tasteless. The cork bark is imported from Catalonia and Andalusia. The cork tree is now grown in Tunis and Algeria; but the bark thence obtained is not yet ripe for use with champagne.

Before the bark possesses the necessary qualities for this special use, the tree must have been stripped from six to eight times; and as the barking is made only once in ten years, the trees must be from sixty to seventy years old before the bark is fit for use with champagne: a worm-hole, or the least fissure, would permit the escape of the effervescent gas.

Packing Room at Messrs. Moet & Chandon’s, Epernay

To resist the explosive force of champagne, it was necessary that the bottles should be so made as to be able to withstand a pressure of from five to six atmospheres; and not until the manufacturers in the glass works of Hautvilliers and of Quinquengrogne made the bottles conical, with narrow, graduated, elongated necks, and very strong, could the wines be fully champagnised. The credit of this discovery is given to Dom Perignon, Prior of the Abbey of Hautvilliers, in 1688.

Moët and Chandon's First Quality Champagnes © 1882 A History of Champagne

The homogeneity of the materials used in making bottles for holding champagne must be complete, and the glass must be free from flints, flaws, and air-bubbles. Further, there must be no salt contained in the glass, or the carbonic acid of the wine would decompose it, and thus the flavor and quality of the wine would be changed.

A little iron gives strength to the glass and is not injurious; but there must not be even a trace of lead. The neck of the bottle must be graduated imperceptibly, and must be free from all protuberance, or "disgorging" would be hindered; it must be so contracted as to compress the cork within the bottle.

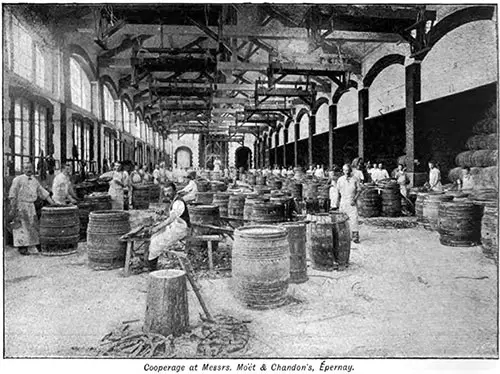

Cooperage at Messrs. Moet & Chandon, Epernay

From these details, it will be seen that, to prevent the finest brands of champagne from being vitiated by the bottles or by the corks, the most minute and careful attention is requisite.

All producers of champagne prepare and blend their wines in accordance with tradition and the standard of the house concerned: the principal makers have only one quality—the best; none of these supply wine of second-class quality with their own distinctive brand.

Best champagnes vary only in degrees of sweetness, and this variation is made to suit the different countries into which they are sent. After the wine has been finally corked the bottles are stored in separate cellars underground, the cellars being divided and set apart for various countries for which the wine has been specially prepared: there is an English cellar, an American, a German, a Russian, etc., etc.

Two of the principal champagne houses of France have been governed for many years by widows—Madame Clicquot-Ponsardin and Madame Pommery— whose husbands have died suddenly.

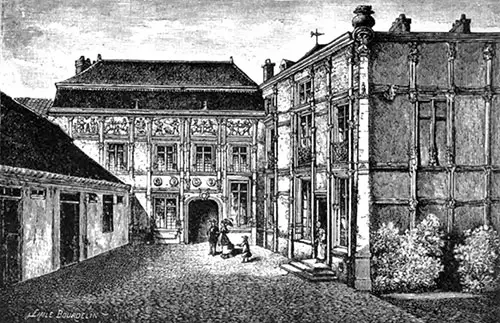

Residence of the Late Madame Clicquot-Ponsardin, Rheims

The house La Veuve Clicquot was established in 1786, also known as Veuve Clicquot-Pousardin.

The Clicquot cellars are situated in the Rue du Temple, being excavated in the earth from 75 to 100 feet below the surface and are carried to a considerable length under Rheims.

Two essential requisites to the "health" of champagne are thus secured: absolute stillness for the wine; and all but perfect equality of temperature throughout the year.

These cellars are lighted by gas; they hold from 12,000,000 to 14,000,000 bottles of champagne, of various ages, and they represent an enormous capital, increasing in value from year to year. The house employs about six hundred hands.

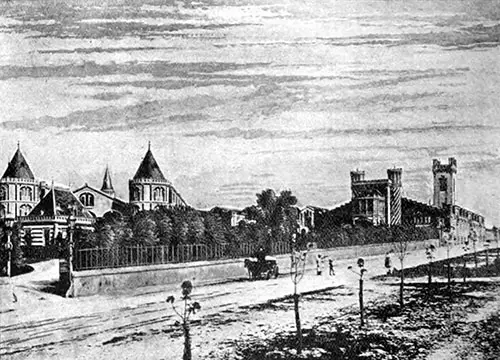

The Establishments of Veuve Pommery, Rheims

On a hill outside the city of Rheims stands the extensive establishment of Madame Veuve Pommery & Co., surrounded by gardens. On passing through some of the offices, the door is reached which opens upon a descent of a hundred steps leading into the vaults.

These extend in various directions for several miles under the city and give warehouse room for about 15,000,000 bottles and hundreds of casks of wine in process of maturation. The illuminant throughout is electricity, and here all the processes attendant upon the production of the finest crus of champagne are developed.

J. Russell Endean, "A Romance in Champagne" in The Pall Mall Magazine, London: Hazell, Watson & Vincy, Ltd., Vol. III, No. 3, July 1894, p. 492-508. Edited by E. B. Gjenvick, 2019.