Women Marines in World War I - 1974

Marine Reservists (f) on the Ellipse behind the White House "Dress Right, Dress" in Preparation for Drill in 1918. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1973ddc36e

Introduction

Legend has it that the first woman Marine was Lucy Brewer who supposedly served, disguised as a man, on hoard the frigate Constitution in the war of 1812. While there is no evidence that Miss Brewer ever wore a Marine uniform there can be no question about Opha Johnson, who on 13 August 1918 enrolled in the Marine Corps to become America's first woman Marine. Her enlistment was a reflection of the dramatic changes in the status of women wrought by the entry of the United States into World War I.

The nation was already heavily committed to the support of the Allies when the declaration of war was signed in April 1917, and as thousands of young men rushed to volunteer for the Armed Services, and the draft gathered in hundreds more, the labor potential of women for the first time in the history of the United States became, of monumental importance.

In August 1917, four months after the Navy opened its doors to women in an effort to support the increasing administrative demands of the war, the Secretary of the Navy said: "In my opinion the importance of the part which our American women play in the successful prosecution of the war cannot be overestimated."

In October of that same year the New Republic commented: "Our output of the necessities of war must increase at the same time that we must provide for the needs of the civil populations of 'the countries allied with us. Where are we to get the lahor?...The chief potential resource at our, command lies evidently in the increased employment of women."

Overnight, organizations such as the National League for Women's Services and the Women's Committee of the Council of National Defense were established to coordinate and direct the activities of women across the country. Everyone, from housewives in Oklahoma to Park Avenue society girls was involved in the all-out effort to support the war.

Much of the work fell within the area of volunteer labor and thousands of women were recruited to work at home or in local women's clubs making bandages, knitting garments, planting victory gardens, or canning a can for Uncle Sam.

Women with more time moved out of their traditional roles and volunteered to hostess at canteens, organize food and clothing drives, or collect books and magazines for the boys overseas.

Hundreds more canvassed the city streets promoting the sale of Liberty Bonds and War Savings Stamps or joined such organizations as the American Red Cross or the bloomer-clad Women's Land Army whose members helped farmers with the task of producing the Nation's food supply.

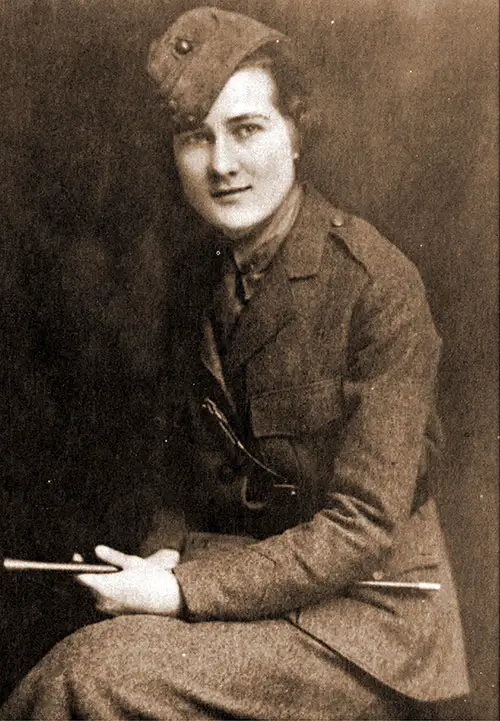

Private Opha Mae Johnson, the Marine Corps' First Enlisted Woman, Shortly after Her Enrollment on 13 August 1918. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1973eff459

The contribution made by the highly-motivated women's "volunteer" army was invaluable to the war effort; however, of greater historical significance was the breakthrough achieved by women in the gainful occupations.

Contrary to predictions early in the war that women would never be put into "trousers or an unbecoming uniform and try to do something a man can do better," women donned the uniforms of elevator operators, streetcar conductors, postmen, and industrial workers, and ably carried on the Nation's business at home.

Dramatic changes in the status of American women were to result from the wide-spread employment of women in United States industry.

Although women were by no means new to the industrial setting, World War I was the first time in which they were employed in large numbers to perform skilled and semi—skilled labor. In aircraft plants, steel mills, and shipbuilding yards, hundreds of women were recurited to operate drill presses, lathes, millers, and other machines and hand tools requiring a high degree of dexterity.

Although American industry and business were the first to feel the pinch of the manpower shortage, and the first to employ large numbers of women, by 1917, the military services were also faced with a serious personnel problem.

Josephus Daniels, the Secretary of the Navy who was enthusiastic about the possibility of enrolling women in other than nursing billets, set his staff to work investigating the legal statutes regarding naval enlistments.

While his assistants tried their best to find laws prohibiting female enlistments, there was in fact no legal basis on which to exclude women — naval law referred only to the enlistment of "persons."

So Secretary Daniels opened the Navy to women under the conditions of equal opportunity. In all, some 12,500 Yeomen (F), holding mostly clerical positions, responded to the nationwide "Call to Colors" broadcast in March of 1917.

The Army which also desperately needed administrative support and would have welcomed women was not so fortunate. The law pertaining to the Army specifically called for the enlistment of "male persons."

In spite of a deluge of requests from hundreds of commanders, all attempts failed to change the law and women were not to be enlisted into the Army until the outbreak of the Second World War.

The position in which the Marine Corps found itself with regard to personnel was similar to that existing in the other services. The way in which the Corps sought out to remedy its situation, with many colorful rememberances by the women who served, will unfold in the following pages of this monograph.

Authorization

By July 1918 the demands of the war hit an all—time high, the heavy fighting and mounting casualties abroad were increas— ing an already acute shortage of trained personnel and as fast as men could be spared, they were sent to join Marine units at the front in France.

When it was discovered that there was a sizable number of battle-ready Marines still doing clerical work in the United States who were urgently needed overseas, the Corps turned in desperation to the female business world.

Major General Commandant George Barnett, in an effort to determine how many men could be released, dispatched memorandums to the offices of the Quartermaster, Paymaster, and Adjutant and Inspector asking for an analysis by the directors of each as to the feasibility of using women as replacements for male troops.

In every case it was agreed that there were areas in which women with clerical skills could be utilized on an immediate basis. Interestingly enough, although'it was estimated that about 40 percent of the work at Headquarters could be performed equally well by women, it was believed that a larger number of women than men would be needed to do the same amount of work. The opinion expressed by experienced clerks was "that the ratio would be about three to two."

The highly competent performance of the women reservists throughout their participation in the war proved the error of this early opinion.

In addition, the Major General Commandant was strongly advised that if women were to be enrolled "it would not be desirable to make the change suddenly but gradually" to allow sufficient time for each woman to be instructed by the clerks they would be relieving.

On the basis of these conclusions and recommendations, General Barnett wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Navy on 2 August 1918 requesting authority "to enroll women in the Marine Corps Reserve for clerical duty at Headquarters Marine Corps and at other Marine Corps offices in the United States where their services might be utilized to replace men who may be qualified for active field service."

In a letter dated 8 August 1918, Secretary Josephus Daniels gave his official approval to the request and authority was granted to enroll women as members.

Recruiting and Enrollment

Overnight the word was spread via newspapers and enthusiastic Marines and on 13 August 1918 women by the thousands flooded into recruiting offices across the country.

Mrs. Opha Mae Johnson, who was working at Headquarters Marine Corps as a civil service employee, was enrolled on 13 August 1918 and holds the honor of being America's first woman Marine. Mrs. Johnson was assigned as a clerk in the office of the Quartermaster General, Brigadier General Charles McCawley, and by the war's end was the senior enlisted woman with the rank of sergeant.

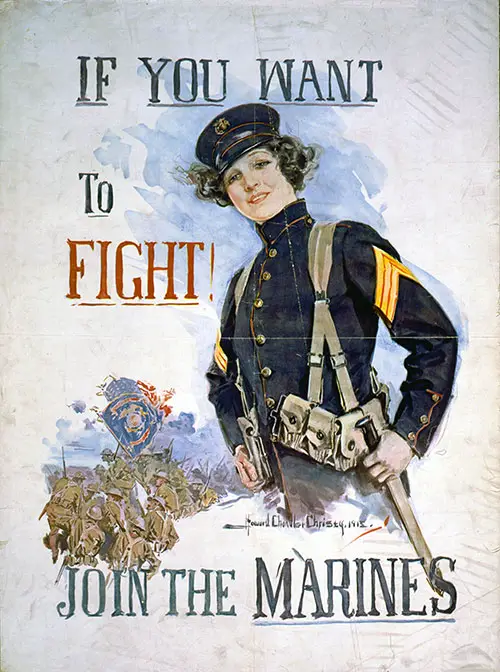

A Fanciful Woman Marine Was Used by Howard Chandler Christie as His Model in This World War I Recruiting Poster. If you want to fight! Join the Marines. Poster Showing Half-length Portrait of a Woman in Military Uniform, and a Trench Warfare Scene with Troops Carrying the U.S. Flag and the Flag of the Marines. American War Poster by Howard Chandler Christy, 1915. Library of Congress, LC # 95500952. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1974700e53

The Marine Corps had very definite ideas as to the type of women it wanted as rr'embers of the Corps. Recruiting officers were instructed to enroll only women of excellent character, neat appearance, and with business or office experience.

While the greatest need was for stenographers, bookkeepers, accountants, and typists, "applicants who have had considerable experience in handling correspondence and general office work and can show evidence of exceptional ability in this line will be given consideration."

Recruiting orders stipulated that women reservists were to be between 18 and 40 years of age but that an applicant slightly under 18 years of age, who is in every respect very desirable, may be enrolled with the consent of her parents."

In addition, each applicant was required to submit to a thorough physical examination before her final acceptance. While this seemed a simple task, it presented unusual problems as the enlistment requirements established by Naval Medical Regulations were designed for men only.

Medical officers, it seems, were as uneasy with the situation as were the women applicants when it came time for the examination. In an effort to establish a policy guiding medical officers, Headquarters released a "circular" on 14 August 1918 giving detailed instructions as to the enlistment requirements expected.

While the Bureau of Medicine realized the obvious source of embarrassment caused by the examination, it was strongly felt that thoroughness should not be sacrificed because of it.

Accordingly, each medical examiner was instructed to "use such tact and courtesy as will avoid offending in any way the sensibilities of the applicant. He shall not, however, by such attitude, allow himself to deviate from a proper fullfiliment of all the requirements. The applicant should be previously instructed to arrange her clothing in a way that will insure ease, facility and thoroughness in the examination. A loose gown of light material will not interfere with the examination or taking of the measurements. Corsets should invariably be removed."

The women selected for duty with the Marine Corps were enrolled as privates in the Marine Corps Reserve, Class 4, for a period of four years.

Each applicant was required to furnish three letters of recommendation and if possible was given an interview with the head of the office in which she was to he assigned.

In cases where applications were received from great distances away and it was apparent that the applicants involved possessed the required skills,

Headquarters Marine Corps ordered that "they should be instructed to report at the nearest recruiting station for examination and a test as to ability and in such cases should be required to furnish additional letters from former employers of undoubted reliability."

Such was the case with Miss Sarah Jones who because of her excellent qualifications was ordered from Meridian, Mississippi to New Orleans, Louisiana for interview and processing.

Following her enrollment on 27 September 1918, Private Jones returned to her home in Meridian to await orders from Headquarters Marine Corps directing her to report.

Within a matter of days the official orders arrived and with excited expectation she boarded the Pullman for the two-day train trip to Washington.

Upon her arrival Private Jones was assigned as a secretary to the non—commissioned officer in charge of medals and decorations where she was to remain until the war's end.

The enthusiasm with which women across the country responded to the call for volunteers was amazing. In New York City alone, 2,000 hopeful applicants lined up at the 23d Street recruiting office in reply to a newspaper article which read that the Marine Corps was looking for "intelligent young women."

Colonel Albert McLemore, the Officer in Charge of Marine Corps Recruiting, was on hand to ensure proper screening and processing of the women. Among the five ladies chosen on that occasion was Miss Florence Gertler who recalled the day's excitement:

Male noncommissioned officers went up and down the line asking questions about experience, family responsibilities, etc., and by the process of elimination got the line down to a few hundred. Applicants were interviewed by one officer and finally given a stenographic test. Colonel McLemore conducted the shorthand test and dictated so fast, that one after another left the room.

Those who remained were taken, one-by—one, into Colonel McLemore's office and told to read back their notes (I remember that I made a mistake on 'Judge Advocate General,' never having heard the word, I thought it was 'Attorney General.')

If the colonel was satisi— fied with our reading, we were required to type our notes and timed for speed and accuracy. More and more applicants dropped by the wayside, until only five of us were left. We were told to report back the next day for a physical examination.

Within a week all five were called up to be sworn in and issued orders for duty at Headquarters Marine Corps in Washington D.C. Florence later learned that Colonel McLemore called them his "100% girls" because of the unusually high speed and accuracy requirements placed on them that first day of recruiting.

Because of her experience as a stenographer and her superior test results, Florence was assigned as a secretary to the Assistant Adjutant and Inspector, Captain France C. Cushing.

Women Enlist in U.S. Marine Corps. Women Are Being Enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps for the First Time as Stenographers Typists and Bookkeepers Etc. Group of Female Applicants; the First to Volunteer for the Service from New York City. Photograph © International Film Service, 19 August 1918. National Archives & Records Administration 165-WW-598A-12 NARA ID # 45568009. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1974bca9ac

Dressed in Men's Uniforms, (l to r) Violet Van Wagner, Marie Schlight, Florence Wiedinger, Isabelle Balfour, Janet Kurgan, Edith Barton, and Helen Dupont Are Sworn in as Privates at New York. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 19753e7639

The Marine Corps was unwavering in its determination to accept nothing but the best, most highly trained women possi- ble. Across the Nation the story was the same.

Among the thousands of women who burned with partiotic desire to serve the country as a woman reservist only a select few were able to meet the rigid requirements demanded by the Corps. In all, only 305 were enrolled during the four months of recruiting.

It was not unusual to find that out of 400 applicants only one had been chosen or that out of 2,000 only five were found to be qualified. Time could not be wasted training.

The women chosen were enrolled with the idea that they would be able to step in and be on their own within a matter of days and in some cases within a matter of hours after their arrival.

These women had to be "top notch" and had to be able to demonstrate their qualifications under the pressure of a stiff recruiting examination.

One young woman by the name of Elizabeth Shoemaker was not to be discouraged in her effort to qualify for enrollment. Miss Shoemaker was working as a stenographer in New York City when she saw the notice in the New York Times that enlistments would open up the next day at the 23d Street recruiting office.

Although she arrived early, the line was already clear around the block and down the street from the front of the station so she took her place at the end and began to inch toward the door arid up the stairs to the office where interviews and examinations were being conducted.

One by one the women were told to step aside "You had to be 100% perfect mentally and physically...and you also had to be a speed stenographer." In spite of the fact that she worked as a speed stenographer, Miss Shoemaker failed the typing test that day and was told that she could not be used:

I was terribly disappointed, of course... the next day I went back and for no good reason... I was only 17, I hadn't had my 18th birthday yet... I did my hair differently and had dressed differently. I thought I might be recognized, and I was. This amazing colonel said, "Weren't you here yesterday"?... I remember him hesitating and when I said "Yes, I was" he got up and leaned over the desk and shook my hand arid said, "That's the spirit that will lick the Germans, I will allow you to take the test again"!

This time she passed the test with flying colors and was on her way to Washington D.C. for duty where she was assigned as the secretary to the chief clerk in the office of the Adjutant and Inspector.

The spirit of these first women Marines is indeed something to be admired. While the reasons behind their desire to enroll in the Marine Corps were as varied as their numbers, the patriotic duty felt by each to be of service to their country in time of conflict was the force stronger than any other which accounted for the overwhelming response to the call for volunteers.

Two Hopeful Applicants to Become Women Marines Are Interviewed by a Recruiting Officer in Boston. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1975725e24

Six Newly Enlisted Privates from Boston Pose for Their Picture before Taking the Train to Washington, D. C. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 19757789a8

Some, like Private Theresa Lake, who was working as a statistician for the Texas Oil Company, has a special reason for enrolling——her sweetheart had given his life for his country. Others, like Private Lillian Patterson, served to support her husband at the front and Private Mary English her brother.

The women of 1918 wanted to be totally involved, and, recalled Private Mary Sharkey, the opportunity to be members of "such an elite branch of the service" was the opportunity to serve in the most meaningful way possible.

One young woman was so filled with the desire to be a Marine that after being told that she did not meet the requirements because she was not a stenographer burst into tears, "But I'll do anything," she pleaded, "anything."

The Macias family of Jersey City, N.J. was well represented in the Corps when its only daughters, Edith and Sarah, were sworn in in New York on 5 September 1918.

Edith and Sara had been working as stenographers in New York when they saw the classified advertisement that the Marine Corps was accepting women.

They both had good clerical and stenographic experience and were sure that they possessed the necessary qualifications for enrollment.

Sarah was 27 years old, and Edith, although only 17, had been telling her bosses and the D. Appleton Publishing Company that she was 19, so, she thought, why not the Marine Corps too?

After a lengthly discussion with the recruiting officers concerning background and experience, the girls were given a physical examination, medical shots, and the stenographic test.

Edith in her excitement failed the test and was going to be turned down, so Sarah bravely asked permission to talk to Colonel McLemore, the senior recruiting officer, and succeeded in convincing him of Edith's ability.

They were both sworn in on that day and ordered to report the following Monday to Washington for assignment. Although their parents "nearly fainted" when the girls broke the news of their enrollment, the two silk stars found hanging in the window of the Macias home the next day was proof indeed of the tremendous pride felt by their family.

Privates Edith and Sarah were detailed for assignment together as stenographers in the office of the Adjutant and Inspector. Upon their discharge, Edith had attained the rank of private first class and Sarah the rank of corporal.

Another pair of sisters who patriotically enrolled in the Corps together was Helen Constance Dupont, whose husband was serving in France, and Janet Kurgan. The newly enrolled Marine Reservists (F) were as proud of the traditions of the Corps as the men themselves.

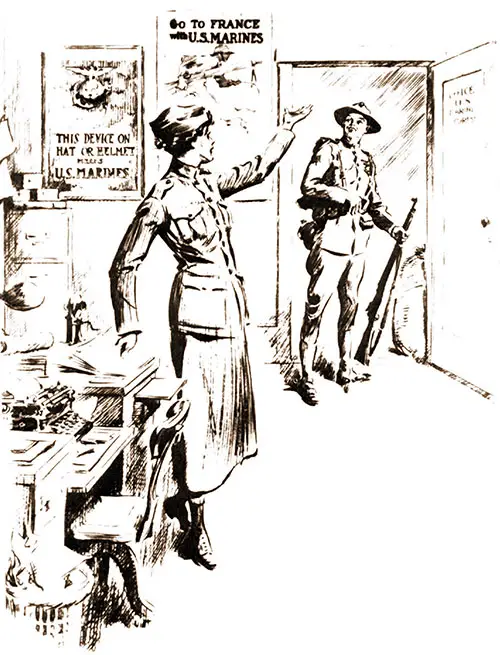

Marine Corps Artist Morgan Dennis Pictures a Newly Arrived Woman Marine Waving "Goodbye" to the Marine She Released for Overseas Duty. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1975cb5f43

While some of their families and friends might have reacted with surprise and in a few cases shocked disbelief, the women themselves were delighted with their achievement.

From the very outset Marine Corps policies and expectations were made unquestionably clearto the aspiring applicants. The women enrolled were advised in no uncertain terms that the same rules and regulations governing enlisted male Marines would also govern enlisted women and that failure on the part of any woman to maintain the high standards expected of a Marine would result in the individual being 'summarily disenrolled."

Colonel Albert S. McLemore made doubly sure that the women to whom he personally administered the oath understood the seriousness of their pledge of allegiance when he warned that he "wanted it distinctly understood that there was to be no flirtatious philandering with the enlisted men at headquarters on the part of the female reservists."

Continually throughout the months between August and November small groups of Marine reservists (F) arrived at Headquarters Marine Corps from cities across the country Although they were dressed in civilian clothes looking like any other young ladies of the time, they were expected to conduct themselves with a degree of military bearina.

Where Joint Travel Orders were issued, one woman was placed in charge and was instructed to represent the group and to handle any problems arising during the course of the journey.

Meal tickets were supplied by the individual recruiting stations in sufficient quantity to cover the trip, and travel tickets were issued for those who traveled by rail.

Sergeant Margaret L. Powers, who was one among five enrolled in Boston on 18 September 1918, remembered how excited they were when they were met at Union Station and whisked off to Headquarters in a mini-bus-like motor car called a "Black—Maria."

Although Headquarters endeavored to have a representa- tive on hand to meet each band of reservists, the effort was not always successful and in those cases the women took the initiative without hesitation and reported in on their own to Headquarters Marine Corps which was located in the Walker Johnson Building at 17th and New York Avenue in downtown Washington.

Name

Marine Reserve (F) was the only official title by which the Corps first enlisted women were known, however, throughout the duration of their service many nicknames were also coined to identify them.

On the occasion of their first official visit to Quantico on 21 November 1918, Corporal Elizabeth Shoemaker heard the title "Lady Hell Cats" used for the first time when an enthusiastic Marine shouted it from the crowd as they marched by.

During a party planned for the women that same evening, Corporal Shoemaker recalled overhearing one disgruntled young Marine telling his buddies: "This is a fallen outfit when they start enlisting skirts," hence "skirt Marines" was added to the growing list.

The most popular and most widely used of all the nick- names was "rIarinette." "The United States Marine Corps frowned upon the use of the word 'Marinette,' " remembered Corporal Avadney Flea, "they posted notices every once in a while on the bulletin board, that we were not to be referred to as 'Marinettes.'

We were United States Marine Corps Reserves with 'F' in parenthesis after indicating female. And we were not to be called 'Narinettes.' The Marine Corps didn't like it."

In spite of that fact, however, many people still refer, although erroneously so, to the Marine Reserves (F) as Marinettes.

Housing

For those not already living in Washington, the first order of business after reporting in was to arrange for housing. Although the military maintained a limited number of government barracks, they were already filled to overflowing with permanent male personnel and a constant stream of transient troops, so the women were given an allowance for subsistence and quarters (approximately $83.40 per month) and assisted in locating quarters in the city.

Private Ingrid Jonassen, who was enrolled in New York on 14 September 1918, remembers how her group enthusiastically bought the Sunday paper their first day in Washington and threw it all away but the classified ads: "We were bound and determined to stay together and continued to look, fruitlessly, all that Sunday. In the end, however, we were forced to hire singly."

The housing shortage by 1918 had reached critical dimensions in Washington and even with the referrals supplied by Marine Corps Housing suitable rentals were hard to find.

Complicating matters even worse was the fact that a deadly strain of Spanish influenza was sweeping the city that summer leaving hundreds of dead in its wake. "If anyone even coughed or cleared her throat she was suspect," recalled Sergeant Margaret Powers.

The women ended up scattered throughout the city, some found rooms alone in private homes and boarding houses while others in small groups rented apartments.

Cooking presented little problem for those who rented apartments or boarding house rooms, however, meals were rarely included in the single room rentals and most of these women ate in cafes or restaurants in the city.

The effects of the influenza epidemic could not be escaped here either, though, and finding available restaurants during the summer months was at times a problem:

"We would have to go in and stand third behind somebody who was seated and wait for the two ahead of us to be served, eat and leave before we could be seated," commented Corporal Avadney Hae.

When the housing dilemma was brought to the attention of Mrs. John D. Rockfeller, a member of the War Council, and an enthusiastic advocate of women in the military, additional help was soon on the way.

Through her efforts about seventy women Marines were quartered in the Georgetown Preparatory School located in Rockville, Maryland, which although newly built had not yet been opened.

Sergeant Margaret Powers who was enrolled in Boston was one among the lucky seventy: "It was a beautiful place with private rooms, and excellent food prepared by a former tearoom owner."

Living in the city had its advantages, however, and the women who were fortunate enough to find quarters near downtown Washington enjoyed a short walk to work while others who were located in the suburbs of Maryland and Virginia rode the trolley cars which faithfully clanged and whistled along their daily routes into the city.

In general the girls found Washington residents to be people of great kindness, such as the lady in Maryland who temporarily set up her sun porch "dormitory style" to accommodate a somewhat discouraged group of six after their long day's search.

Sergeant Ingrid Jonassen will also never forget her landlady, Mrs. Pheobus, who helped her through a serious bout with the Spanish flu.

Looking Trim in Their New Uniforms (l to r) Pfcs Mary Kelly, May O'keefe, and Ruth Spike Pose at Headquarters Marine Corps. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1975ea5be4

Members of the Adjutant and Inspector's Office Staff Pose for a Picture in October 1918; in the Foreground Are Privates Bess Dickerson (left) and Charlotte Titsworth. Photo Donated by Mrs. Charlotte (Titsworth) Austin. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1975f54290

In spite of the fact that the worrn were spread far and wide across the city they none-the-less maintained a strong feeling of comradeship with one another and whenever possible were eager to be together as a group, whether at social functions, drilling on the Ellipse behind the White House, or participating in parades and rallies.

Uniforms

As women organized into groups in their effort to support the war, hundreds of unusual uniforms began popping up across the country. Among the most admired, by far, was the uniform designed by the Quartermaster for the Marine Corps Reservists (F). "The civilian girls were terribly envious," recalled Ingrid Jonassen, "and tried on occasion to borrow my uniform."

The girls looked stylish indeed in their tailormade two-piece suits of green wool in the winter and tan khaki in the summer. Accessories included: a specially designed shirt, regulation necktie and overcoat, brown high-topped shoes for winter and oxfords for spring and summer - the first low shoes most of them had ever worn.

Matching overseas caps on which they proudly wore the globe and anchor insignia were the preferred headgear; however, during inclement weather the women reservists were permitted to wear campaign hats which made "excellent uirellas," recollected Private Florence Gertler "and were really quite comfortable and practical when it rained."

Raincoats, gloves, and purses were not issued, and while old photographs show some women wearing gloves, handbags were not permitted on any occasion.

Although initially each woman had only one winter uniform set, the standard uniform issue was established as: two winter and three summer uniforms, which, in addition to jackets and skirts, consisted of six shirts, one overcoat, two neckties, two pair of high topped shoes, and two pair of oxfords.

The women did not have a dress uniform. As individual items became unserviceable through "fair wear and tear," the Quartermaster's Department replaced them on an exchange basis.

Private Carrie E. Kenny Pictured in Her World War I Uniform in 1919; She Continued to Serve the Marine Corps as a Civil Servant for 26 Years following Her Release from Active Duty. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 1976176f9f

The uniform regulations governing women reservists were no less strict and no less important than those governing male Marines and most of the women took great pride in keeping their uniforms "spick-and-span" and their shoes polished to Marine Corps standards. "Even though the uniform regulations were strict," commented Private Mary Sharkey, "the women used their ingenuity and were put to relatively little inconvenience":

The coat or blouse had a large pocket on each side which extended across the front. These commodious cavities were handy, but putting too many things in them created bulges which was strictly against regulations.

To avoid this I kept a comb and brush in my desk, tucked my handkerchief inside a sleeve, and carried a small change purse so as to appear trim and neat. There was no need for a wallet.

Our underwear and stockings we bought ourselves. The skirts were heavy enough not to require a slip, but if one wore a slip it tended to bunch up in front while walking or marching, so I wore long bloomers over my underpants. They stayed in place nicely.

The skirt had to reach the tops of our high-tied, pointed-toed, curved—heeled shoes. Our overseas cap was made with a fold that could be released and buttoned under the chin, thereb" covering hair and ears.

The cap was of the same material as the uniform. My quarters had laundering and ironing facilities, so I encountered no difficulty in maintaining cleanliness...Initially we each had only one winter field uniform and when it was sent out to he dry cleaned we requested permission to wear civilian clothes for that day only.

Although the Navy women also had uniform regulations, they were quite a bit less strict than those governing Marine women reservists "The Navy Department girls were quite a bit more feminized," remarked Corporal Elizabeth Shoemaker.

"Enlisted women in the Department were not subject to the same discipline as were the Marine girls. For instance, while the Navy girls wore lace collars and jewelry, the Marine girls, even on the hottest Washington summer day, were not allowed to turn down their collars or remove their fore-in-hand neckties."

Violations of the uniform code while only occasionally disciplined were continually brought to the attention of the women reservists. The following memorandum written in 1919, along with a rather unusual violation in the wearing of a ribbon of high distinction, points up the more common infractions for which the women were reprimanded:

HEADQUARTERS U.S. MARINE CORPS Adjutant and Inspector's Department Washington, D. C. February 8, 1919

NORANDUM FOR: THE ADJUTANT AND INSPECTOR, THE PAYMASTER, THE QUARTERMASTER

It has come to the attention of the undersigned that there is a total disregard of uniform regulations on the part of a number of female reservists attached to these Headquarters. Several of them have recently been seen in public places wearing rifle insignia, Sam Browne belt, spats and non—regulation shoes. A flagrant example of this disregard of regulations was noted today in the case of a female reservist who was wearing a ribbon of the Croix de Guerre on her coat in the position required by regulations for the wearing of campaign ribbons and ribbons and medals. This is not only a direct violation of uniform requlations but is as well the wearing of a decoration which is awarded by the French Government only for gallantry on the field of action in the face of the enemy.

Female reservists must be made to understand that the wearing of the uniform by them cornfers no priviledqe to deviate from the uniform as prescribed in regulations.

By order of the Major General Commandant.

The most popular uniform item among the wotren reservists was the Sam Browne belt. Although the girls were warned repeatedly against its wearing, "It made the uniform look particular stunning," reminisced Sergeant Jonassen, so most of the women willingly took the risk and wore it whenever they could, on leave and liberty, at rallies and parades.

On one occasion a young woman was seen wearing the belt by the major for whom she worked and the next morning she found herself standing tall being sternly reprimanded with a warning forbidding her to wear it again.

"Some months later, recalled Corporal Elizabeth Shoemaker, "a great victory parade was held in Washington. General Pershing led it, the girls were in it, and of course all the Marine Corps officers...The day before the parade the orders for dress were posted directing all officers to wear Sam Browne belts.

A mad scramble in the Washington stores to buy belts followed soon after and the stores were quickly sold out. The major who had been so cross at his secretary could not find a single belt in the whole city...An hour before the parade he rang for her and asked if he might borrow hers, he even sent her home in an official car to get it.

Private, Later Corporal, Avadney Hea Dressed in the Favorite Uniform of the Marine Reservists (f) — Winter Field Service Green, with Sam Browne Belt and Swagger Stick. Women Marines in World War I, 1974. | GGA Image ID # 19762d31ea

The women were particularly fond of having their pictures taken in the winter field green uniform, wearing the Sam Browne belt and holding a swagger stick: 'We were permitted to carry a swagger stick," remembered Corporal Mabelle Musser, "which some of us did with high glee - not every day to work, but on special occasions and on Sunday when we went strutting."

Eventually, although officially frowned upon, a liberal policy was adopted with regard to the Sam Browne belt and the reservists when not on duty were permitted to wear it with relatively little repercussion from headquarters.

The women assigned to Washington, D.C. were the first to be completely outfitted in their uniforms since they were able to take irr'mediate advantage of local tailors and the Quartermaster's supplies.

Women recruited for duty in other cities, however, waited months and in some cases did not receive uniforms at all. Private Lucy Ervin, who was assigned to the District Division in Indianapolis, Indiana, after having waited several weeks could wait no longer and ingeniously assembled her own uniform:

I could see that it would be months yet before I could be assured a uniform and since I had always admired the dress uniform of the Marines, I was given permission to wear one of the dress jackets, to which I added a black velvet skirt, web belt complete with red and gold stripes and a campaign hat. I'll tell you I was high off the ground when I walked down the street in it...Many officers were surprised to be given a salute as I passed them...I was just a private in the rear ranks but I was proud to be doing a job that was needed."

In a letter to Headquarters Marine Corps following her discharge Private Ervin told her delightful story and by return mail she received a box from the Quartermaster with material and emblems for a regulation winter field uniform.

After the war when asked about the uniforms worn by the Marine Reservists (F), the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, commented:

The uniforms...of the Marines (F) were natty and beautiful, were worn with pride...and suited to the duty assigned. As a designer of women's uniforms the Navy Department scored a distinct success, for these uniforms were copied by women all over the country."

Pay

The 305 women reservists enrolled between the months of August and November 1918, proved to be a capable and industrious group and by the end of the war a good number had been promoted to private first class, corporal, and sergeant, the highest rank obtainable.

In keeping with Marine Corps policy, the women received the same pay as enlisted men of corresponding rank: private, $15.00; private first class, $18.00; corporal $21.00; and sergeant, $30.00 per month, plus an additional $83.40 per month for subsistance and quarters.

The end of the first payroll period held quite a nice surprise for Private Ingrici Jonassen: "I never expected to be paid for my services," reminisced Sergeant Jonassen, "I thought that we would receive only room and board, so you can imagine my surprise when my first pay check came through."

The women had to work hard to prove themselves and promotions, given for time in grade, time in service, "work well done, and conduct becoming a woman," were worn with the greatest pride and pleasure.

Private First Class Ida Kirkham recalled the unexpected problems she incurred with her initial promotion:

After a few months I received my first promotion to private first class. My stripe, which reminded me of a whisk broom, earned me $3.00 more a month and entitled me to be called "Private." I remember how devastated I was when I was informed that my whisk broom was sewn on upside down. After all, no one had instructed me how to wear that stripe and I sewed it on the way I thought it look- ed best."

By the war's end the senior enlisted woman with the rank of sergeant was Opha Mae Johnson, who worked in the office of the Quartermaster.

Assignments To Duty

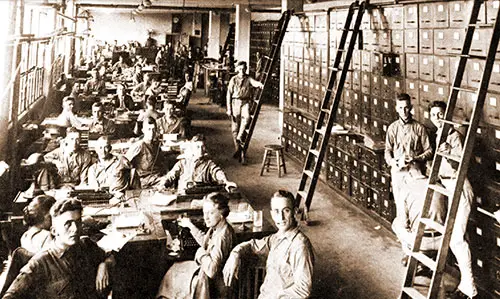

The jaunty women reservists arrived at Headquarters Marine Corps eager for work and little time was wasted preparing them to take the jobs of Marines anxiously awaiting overseas orders. One by one they took their places as secretaries, office clerks, and messengers in the offices of the Adjutant and Inspector;:Paymaster, and Quartermaster.

Captain Lind L. Hewitt, USMCR, "Women Marines in World War I," Washington DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1974, pp. 1-25.