USN First Enlisted Women: “Reporting to Work”

“It will be a source of inspiration to the country at large to learn that the able and conscientious men and women who are devoting their best thoughts and untiring energies to the efficient administration of the NAVY permit no half measures to hurt their support of the National cause, but act as well as think on the spirit that their ALL is not too much.” Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Navy.

The Navy’s first enlisted women worked at naval commands across the United States and overseas, supported Allied operations and campaigns, and contributed directly to the Allied victory.

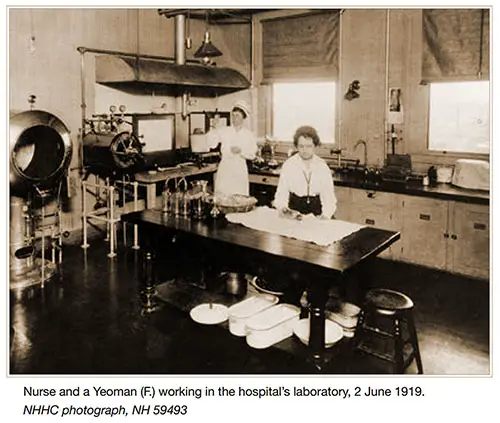

In addition to traditional clerical and administrative duties, these pioneering women assembled munitions, transported classified materials, transcribed documents, and assisted nurses at overseas hospitals.

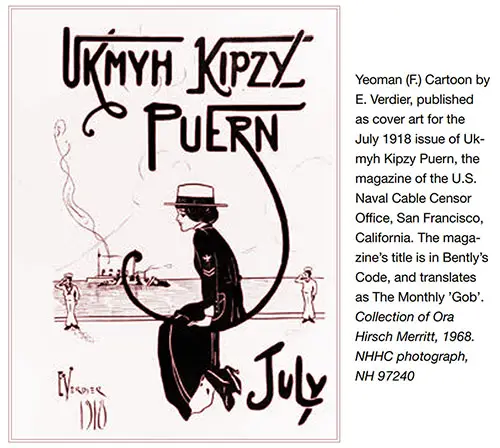

Wilma J. Whitman, for example was one of several yeomen (F.) assigned to U.S. Naval Intelligence, Department Censorship, in San Francisco in 1918.57 The Navy Department could not have survived without women reservists.

They proved themselves so valuable that commanding officers recognized the ability of most individual yeomen (F.) to do the work of several Sailors.

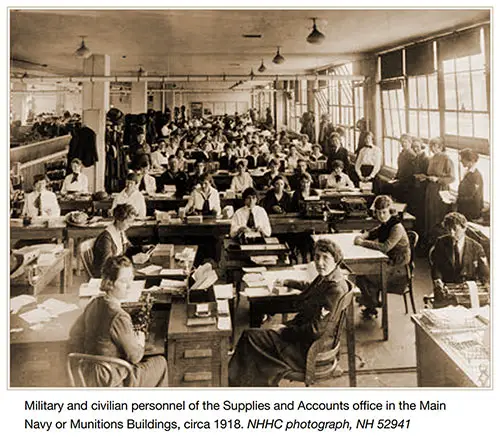

Military and Civilian Personnel of the Supplies and Accounts Office in the Main Navy or Munitions Buildings, circa 1918. NHHC photograph, NH 52941. GGA Image ID # 191c97e464

The female reservists endured long hours, insufficient housing, reduction in their income (in some cases), and public opposition to their enlistment.

During the 1918 influenza epidemic, the Yeomen (F.) worked with patients, increasing their own exposure to the deadly epidemic. Their wartime service gave them a very direct view of the war and historic events (i.e., providing administrative support for the Navy NC-4 seaplane’s first transatlantic flight).

Motivated primarily by patriotism, they responded to President Wilson’s appeal to “Do Your Bit for America” by enlisting in the United States Navy.

Women’s Work

“The war efficiency of the Navy is due, in big part, to the excellent work of the women employed in it . . . the women who have the men’s jobs have shown themselves as efficient as the men.” Rear Admiral Samuel McGowan, Paymaster General of the Navy and Bureau of Supply and Accounts.

Those doing business with the Navy Department likely encountered female yeomen or benefitted from their productivity. Female yeomen labored up to ten hours a day and often for six days a week.

Their clerical duties ranged from typing to dispensing payroll. They prepared and processed much of the Navy’s paperwork, including that which supplied ships and submarines with medical supplies and Sailors with food and uniforms.

They paid those submarine crews in port for resupply or repair and transported classified material. They also drafted condolence letters and other correspondence.

Alice Regina Costello processed death notices, which, unfortunately, placed her in a position to learn of her brother’s death on the job.

Twenty-three female yeomen helped staff the reserve officers’ school, public works school, base hospital, supply department, and medical staff at the Norfolk Naval Operations Base in July 1918.

Maybelle M. Bond worked in the accounting department at Pier 19 in Philadelphia. Eleanor Griffith, an auditor at the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts, signed multimillion-dollar contracts.

Helen O’Neill approved all correspondence prepared in the Division of Enlisted Personnel in the Navy Department. Men could not believe the female voice receiving their call on the switchboard.

Joy Hancock delivered plans from the superintending constructor’s office to the ships under construction in the New York Navy Yard.

She later served as the personnel yeoman at the Naval Air Station, Cape May, New Jersey, where she recorded the proceedings from the naval courts-martial and boards.

District of Columbia native Charlotte L. Winters enlisted with her sister. Charlotte spent the war as a typist at the Naval Gun Factory in the Washington Navy Yard.

The assistant senior inspector to the commandant of the Washington Navy Yard noted 350 female yeomen working in various departments, including Master-at-Arms Third Class Annie Sharp Sietz.

Yeomenettes also conducted non-administrative duties varying from production-line munition assemblers to a Ph.D. bacteriologist. Yeomen (F.) processed fingerprints and designed camouflage for ships.

Dazzle camouflage, also known as “Razzle Dazzle,” was used to distort the ship’s appearance by applying the paint in random geometric patterns, making it harder for the enemy to determine a ship’s weapons, size, length, speed, and course. This had the potential of causing enemy attackers to miscalculate firing solutions.

Nurse and a Yeoman (f.) Working in the Hospital’s Laboratory, 2 June 1919. NHHC photograph, NH 59493. GGA Image ID # 191ca4c549

Chief Yeoman Eunice C. Dessez spent the war at the Naval Reserve Enrollment Office at 10th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, S.E., in Washington, DC, commanded by the afore-mentioned Lieutenant Charles H. Venable.

The staff reached their highest numbers of the war in August 1918 with 1,077 enrollees. Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, escorted interested women to the office.

Venable and his staff walked them through every step in the process from the application to taking the oath of office. Some began work on the first day, but most returned home to await orders.

Venable had two nurses on his staff.62 Dessez praised Venable, “The thousands of Yeomen (F) who passed through the Naval Reserve Enrollment Office at Washington will remember the dignified officer who administered the oath of office to them and signed their service records.”

Their assignments, especially those in naval intelligence jobs, allowed the yeomen (F.) to view the war in real time. Mable Vanderploeg Pease transmitted messages to “Simsadus,” referring to Admiral Sims, U.S. Navy liaison to London.

Florence Whetsel charted submarine activities along the East Coast of the United States. Lillian Budd translated messages from naval ships and commands and delivered them directly to President Woodrow Wilson and members of his cabinet.

Marion Porter Taylor monitored classified Allied ship movement reports in the Atlantic. The staff at the Office of Naval Intelligence in New York included 50 yeomen (F.), some of whom participated in espionage investigations.

A small percentage of the female reservists had assignments outside of the continental United States in Hawaii, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Panama Canal Zone.

Naval Intelligence and Cable and Postal Censorship at the Navy Yard in Pearl Harbor had 30 female yeomen third class on staff. The few working with classified materials did not wear their uniform so as to conceal their duties.

Yeoman (f.) Cartoon by E. Verdier, Published as Cover Art for the July 1918 Issue of Ukmyh Kipzy Puern, the Magazine of the US Naval Cable Censor Office, San Francisco, California. The Magazine’s Title Is in Bently’s Code, and Translates as the Monthly ’gob’. Collection of Ora Hirsch Merritt, 1968. NHHC photograph, NH 97240. GGA Image ID # 191cd114d5

Virginia Sanborn of Kannakai, Molokai, left her position as a stenographer with McInery’s Company to join the Navy after the commandant of the Naval Station Hawaii publicized his immediate need for typists, stenographers, and wireless operators.

Alexandra J. Munro, one of seven female yeomen on staff, served as the stenographer for Commodore Dennis H. Mahan, USN, commodore of the Censorship Bureau.

Chief Yeoman Winifred Gibbon and Chief Yeoman Edith Barron deployed to base hospitals in Paris and Brest, France, respectively. Pauline Bourneauf’s ability to speak fluent French made her an ideal candidate for assignment at Base Hospital No. 1 in Paris. Florence Hooe also worked Paris in the naval attaché’s offices.

Navy Life

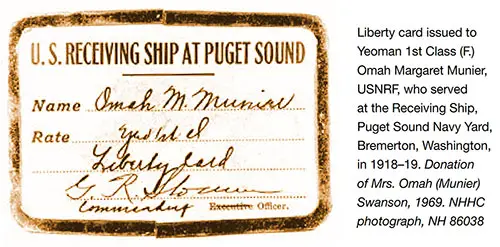

As members of the Naval Reserve Force, the yeomen (F.) were subject to the same rules as their male counterparts. Lieutenant Commander R.N. Marble’s 10 October 1918 memo to the commanding officers at all of the Navy bureaus and offices outlined the administrative guidelines, including the procedures for requesting leave and liberty.

The Bureau of Navigation also distributed mimeographed copies of the two-page explicit instructions entitled “The Guidance of Naval Reservists, Male and Female.”

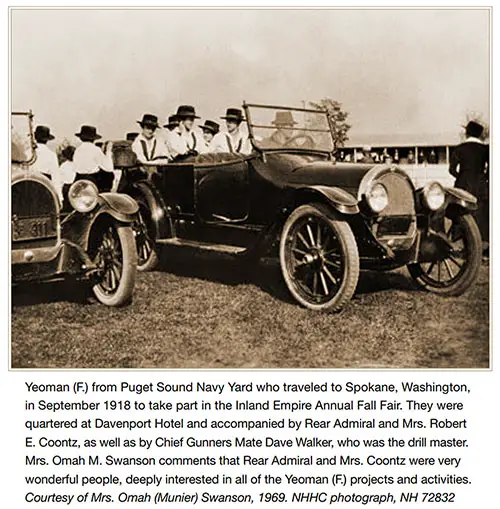

The yeomen (F.) spent their leave and liberty visiting local tourist attractions and friends and attending dances. They played on Navy-sponsored competitive basketball, baseball, track, and swimming teams and they enjoyed picnics, billiards, and the movies.

Some women reservists stationed in the nation’s capital spent their day off supporting the Salvation Army’s doughnut drive. The type of recreational activities varied from one shore establishment to another.

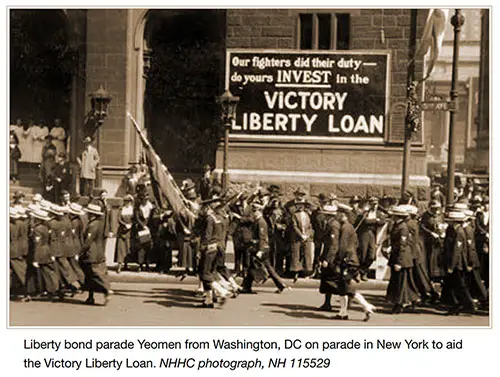

Yeomen (F.) participated in the naval regatta on the Charles River in Boston. Joy Hancock sold liberty bonds at the Keith’s Theater in Philadelphia.

Addie Worth Bagley, wife of Secretary of the Navy Daniels, rented a house at 1720 Massachusetts Avenue to provide a recreation club for Navy women.

Yeomen (F.) assigned to the Boston recruiting office organized rowing and track relay teams. Commanding officers encouraged such activities for morale and esprit de corps.

Yeoman (f.) from Puget Sound Navy Yard Who Traveled to Spokane, Washington, in September 1918 to Take Part in the Inland Empire Annual Fall Fair. They Were Quartered at Davenport Hotel and Accompanied by Rear Admiral and Mrs. Robert E. Coontz, as Well as by Chief Gunners Mate Dave Walker, Who Was the Drill Master. Mrs. Omah M. Swanson Comments That Rear Admiral and Mrs. Coontz Were Very Wonderful People, Deeply Interested in All of the Yeoman (f.) Projects and Activities. Courtesy of Mrs. Omah (Munier) Swanson, 1969. NHHC photograph, NH 72832. GGA Image ID # 191d2ad8be

Mrs. Daniels also organized a yeoman (F.) battalion composed of four companies trained by a Marine staff sergeant to participate in parades and to meet returning military personnel in New York City.

They also greeted President Wilson and senior leaders arriving at Union Station, sold liberty bonds, and sponsored community activities.

In the summer of 1919, the Navy Yard workers hosted field games with children under the age of 16 at the Central High School stadium. The schedule included 50- and 100-yard dashes, hurdles, the broad jump, the pole vault, the relay race, as well as the sack race, and jump rope.

The yeomen (F.) enjoyed being recruiters and did it very well. Their firsthand accounts in the media proved effective tools. Ethel Leona Bergmann, a Washington, DC native, wrote articles about her naval service for the Saturday Evening Post that Navy recruiters used.

Liberty Card Issued to Yeoman 1st Class (f.) Omah Margaret Munier, USNRF, Who Served at the Receiving Ship, Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Washington, in 1918–19. Donation of Mrs. Omah (Munier) Swanson, 1969. NHHC photograph, NH 86038. GGA Image ID # 191d2da5d2

Liberty Bond Parade Yeomen from Washington, DC on Parade in New York to Aid the Victory Liberty Loan. NHHC photograph, NH 115529. GGA Image ID # 191d34d1be

Challenges

The women expecting assignments to a ship were disappointed when they learned that the federal law prohibited such orders. They worked long hours and many jobs were tedious, redundant, and boring.

Yeomen (F.) in sensitive or classified jobs could not share their experiences with others. Some offices functioned at a much higher tempo than others.

The women’s training and drill requirements in the evenings during the week caused them to delay their recreational time until the weekends.

Nell Weston Halstead was so bored with her clerical duties that she complained to her captain and requested orders to France. He responded, “What the hell could a girl do on a battleship? Get back to your job.”

The yeomen (F.) assigned to the wireless office within the cable office at the Censorship Bureau in Hawaii endured the constant rattle of the telegraph keys.

The process started with an officer marking the messages received at the counter with a blue pencil. After several reviews, the telegrapher sent the messages over the Marconi and federal wireless plants for transmission.

Lou MacPherson Guthrie shared, “By now, many more girls were enlisted in the Navy. The work was becoming routine. The glamour was gone.

The boys were overseas. We felt stalemated in Washington. Worse still, a rumor started that we were being moved across the river next to a fertilizer factory in Alexandria. But then suddenly the war was over!”

Recognition

Commanding officers recommended female naval personnel for promotion. The candidates had to take tests administered every quarter to compete for these. Rear Admiral Samuel McGowan was among those recommending yeomen (F.) for officer commissions.

Congressman James A. Gallivan (D-MA) appealed directly to Secretary Daniels that Chief Yeoman Daisy Pratt Erd be commissioned an ensign. Daniels appreciated their efforts, but he lacked the necessary authority. Years later, Daniels remarked,

I regret of these first women in the Navy that there was no provision of law that existed for the promotion as commissioned officers. I could and did enroll them as Yeomen (F.) and Marinettes, but it required legislative action to give them rank as officers. Women did not then have the ballot and Congress looked askance at women in the Navy, as did the old navy ‘sundowners’ who resented their intrusion into what had been an exclusively male organization. In fact, very shortly after the armistice, legislation was enacted directing their demobilization.

Secretary Daniels and his bureau chiefs recognized the contributions by yeomen (F.) in their 1918 annual assessment. Daniels observed, “These women who enrolled were of the elect of their sex, and I do not know how the business of the Department of the Navy yards, and stations and of the districts could have been carried on without them. Their efficiency has again illustrated women’s large part in war work.”

Rear Admiral Leigh C. Palmer, chief of the Bureau of Navigation, wrote: “The civil service clerks and the men and women of the reserve yeoman branch have given excellent service. It would have been impossible to carry on the duties of any of the bureaus or offices of the Navy Department had it not been for the efficient and loyal work of these men and women.”

Rear Admiral Charles W. Parks, chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks reported “The force is now 10 times what it was in July 1916. While the work under the bureau is on the basis of funds available for work under its cognizance has increased approximately 38% during the same period. The services of women have been utilized to a large extent, especially in the clerical force and naval reservists, and to some extent the technical forces.”

The chief of the Hydrographic Office noted, “The carrying on of the increased work resulting from the state of war has been rendered possible by utilizing temporarily the services of men and women of the Naval Reserve Force.”

Surgeon General William Braisted, in his letter commending Yeoman (F.) Kathryn Clark, noted “the great debt the country owes the splendid young women who gave their services so completely and whole heartedly during the trying days of the war.”

Race and Gender Relations

Despite the urgent need for personnel, Secretary Daniels did not recruit all interested women. Recruiters initially turned away African Americans or deemed them unqualified with fabricated reasons.

Individuals questioned this policy of exclusion in letters to Daniels that he chose not to answer. Whatever answer might have been drafted could not have hid the irony of such a decision in a war to make the world safe for democracy.

His policy was consistent with the Navy practice of limiting the number of ratings in which blacks could serve and not promoting them to officer ranks.

Nonetheless, in 1918 14 black women enlisted and worked in the Muster Roll Division at Main Navy supervised by fellow African American John Temple Risher.

Risher, a native of Jackson, Michigan, married Annie Louis Greene, the sister of Armelda Hattie Vawter, one of the 14. Armelda was a clerk in the naval aviation department when Risher recruited her.

She enlisted as a landsman yeoman fourth class, an undesignated rank, and rose to become a yeoman third class. Robert Roster Greene, her father, was an educator and the author of Recollections of the Black Belt (1926). He worked in the nation’s capital as the clerk-in-charge with the railway mail service (1891–1922) and with the post office (1922–1925).

The 14 black female yeomen hailed from three states: Mississippi (7), Texas (2), and Maryland (1), and from the District of Columbia (4).

Courtland Milloy’s 1992 interview with Sarah Davis Taylor, the Maryland native, reported that the Navy disqualified black women in their first efforts to enlist by claiming that they had flat feet.

After the war, she worked as a clerk in the Navy Department for 23 years and had the privilege of being mentored by Dr. E. Franklin Frazier, a renowned sociologist, professor, and scholar at Howard University.

Ruth Welborn, one of the 14 and her grandson, Commerce Secretary Ronald H. Brown are buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Eunice C. Dessez’s First Enlisted Women makes no mention of these pioneering 14 African Americans. Moreover, this author’s research has not revealed how Risher accomplished this or why Daniels allowed him to do so.

In regards to gender, most female yeomen reported that their shipmates and civilian co-workers welcomed them and appreciated their willingness to serve their nation.

Joy Hancock and Lucy and Sidney Burleson described their work environments as respectful and positive. Typically, it was the senior enlisted personnel with decades of service who did not believe women belonged in “their” Navy.

They resented the fact that women could wear “their” uniform without having to meet the sea duty requirements. No one reached the rank of chief petty officer quickly, so these men did not appreciate the women reservists starting their service in that rank.

Naval officers also expressed their displeasure, sometimes in published editorials. After some time, it became evident that once the women learned their job the odds of male Sailors being deployed or receiving orders to a ship actually increased, engendering surprisingly mixed feelings.

According to Yeoman (F.) Mazie Carie of San Diego, “The sailors didn’t like us very much. You see we were all yeomen and they would rather tickle a typewriter than go to sea.

Every time one of us enlisted two men received sea duty.”

Some Sailors had such strong objections to working with women that they requested transfers. Male civilians also shared these negative sentiments.

Agnes Carlson copied naval food orders at the New London Naval Base in Connecticut. Her brother had to defend her honor in a fight with an older civilian who had shared a negative remark about the yeomen (F.).

Naval leaders did not accept such criticism. R. C. Shepherd’s editorial argued the women should not be in the same rating as men because they could not perform the duties and they “cheapen the badge.”

Captain Joseph L. Taussig at the Bureau of Navigation remarked, “There are more [male] yeomen doing shore duty than in any other rating and many of these yeomen have never been to sea and it is beginning to look that even in spite of all our efforts we are not going to be able to get them to sea.

In view of this I see no reason why the yeomen should consider that their rating has been cheapened by the Yeowomen wearing the same badge.”

Publishers also captured supportive commentaries. The May 1917 issue of the Newport (Rhode Island) Daily News recorded:

Every woman who may be called upon to do work of a man will not be worth so much as the man whose place she will take, but . . . it is quite possible that in some cases the substitute will develop enough capacity to make her more valuable than the man she succeeds . . . [the question] is not to really one of sex, but the ability and value.

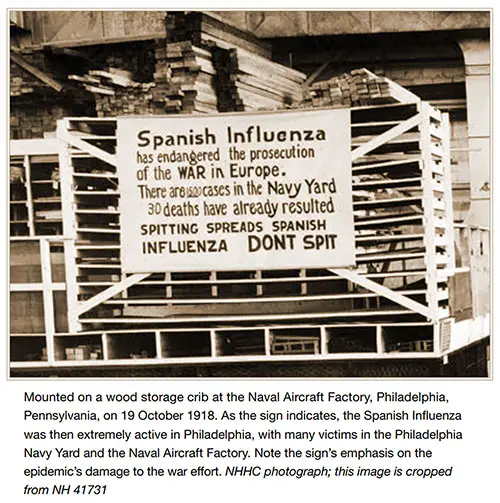

The Spanish Influenza Epidemic

The 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic took millions of lives around the globe. No one was exempt. It struck 57 yeomen (F.), 25 Navy nurses, 2 women Marines. Over 500,000 Americans died between October 1918 and February 1919.

The female enlistees described this disaster as one of the most unusual experiences of their naval service. The international medical community’s best efforts to prevent the spread of the epidemic proved inadequate.

There were too few doctors, funds, and resources to combat it more effectively. Newspapers published advertisements for Father John’s Medicine, laxative bromol quinine tablets, and other products promising to prevent or cure the flu.

The papers also featured information about the methods citizens should take to protect themselves and their communities such as wearing a mask at all times, isolating the sick, and burying victims quickly.

The influenza overwhelmed hospitals and morgues. The very young and the elderly were particularly vulnerable. The population was discouraged from attending large gatherings and ordered to stay home if they had any symptoms.

As the virus progressed, public health officials closed movie theaters, schools, businesses, and factories. People compared this catastrophe to the plague. Ships arriving in Europe delivered troops and Sailors at various stages of illness.

Mounted on a Wood Storage Crib at the Naval Aircraft Factory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 19 October 1918. As the Sign Indicates, the Spanish Influenza Was Then Extremely Active in Philadelphia, with Many Victims in the Philadelphia Navy Yard and the Naval Aircraft Factory. Note the Sign’s Emphasis on the Epidemic’s Damage to the War Effort. NHHC photograph; This Image Is Cropped From NH 41731. GGA Image ID # 191d519652

Olive Stark O’Sullivan, stationed at the State Pier and Experimental Station in New London, Connecticut, remembered, “It was a particularly virulent type of flu. And the deaths were many.

A person would be absent one day and the next day you heard he was dead. I roomed across town from the pier and it seemed I could never go to and from without seeing a flag-draped coffin en route to the railroad station.” Yeoman (F.) Estelle Kemper recalled,

During the epidemic I went early to the office, armed with a big bottle of disinfectant and washed all the desks and chairs and telephones with the bug-killer.

Just the same, it seemed to me that every morning somebody else was missing from his or her desk, and all too often when I called a phone number, I learned the clerk had died overnight.

We were winning the war in Europe, but for a few weeks death seemed to have put his awful finger on our capital city.

Admiral Sims, reported to Washington from London: “There is no doubt that this epidemic is now greater threat to people on ship-board than the submarine is.”

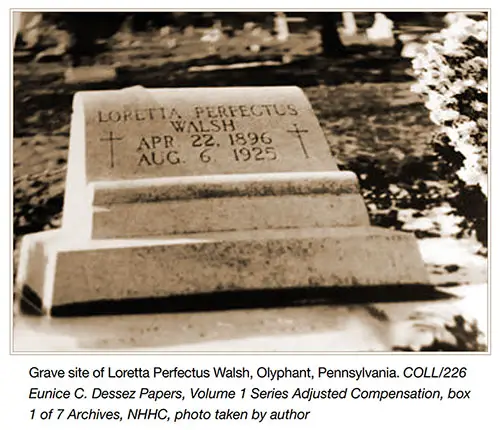

Yeoman (F.) Loretta Perfectus Walsh became ill and recovered, but her exposure shortened her life. She died from a related cause on 6 August 1925.

Grave site of Loretta Perfectus Walsh, Olyphant, Pennsylvania. COLL/226 Eunice C. Dessez Papers, Volume 1 Series Adjusted Compensation, box 1 of 7 Archives, NHHC, Photo Taken by Author. GGA Image ID # 191dac2b4d

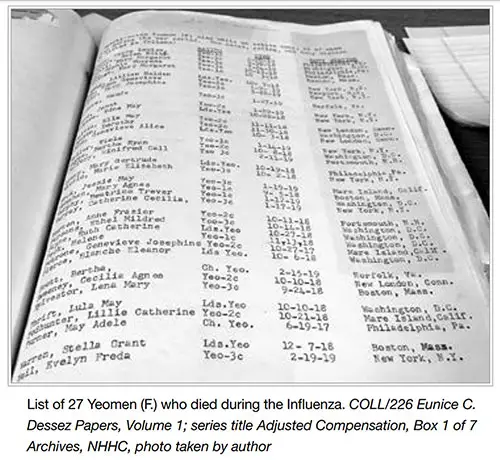

List of 27 Yeomen (f.) Who Died during the Influenza. Coll/226 Eunice C. Dessez Papers, Volume 1; Series Title Adjusted Compensation, Box 1 of 7 Archives, NHHC, Photo Taken by Author. GGA Image ID # 191db4856d

“Let every man and every woman assure the duty of careful, provident use and expenditures as a public duty, as a dictate of patriotism which one can expect ever to be excused or forgiven for ignoring. . . . The supreme test of our nation has come and we must all, speak, act and serve together.” President Thomas Woodrow Wilson, Proclamation to the American People.

The yeomen (F.) did that and much more. They courageously accepted the President’s charge. They were the nation’s first enlisted women and they forever changed the United States Navy.

The recommendations to commission them and the potential for one yeoman (F.) to relieve two male sailors documented their outstanding job performance and potential.

They dispelled the prevalent myths and fears about women enlisting. Eventually, the women’s productivity and performance transformed some of their harshest critics into their supporters.

Moreover, their male counterparts came to realize that the women had enlisted for some of the same reasons as they had—patriotism and defeating the Germans.

The yeomen (F.) increased efficiency rates, proving that the Navy was better with them than without them. Their work in munitions, camouflage, deciphering, and other specialty functions saved lives and made critical contributions to the success of the nation’s war effort.

Moreover, their naval service enhanced their lives. The yeomen (F.) had a significant role in capturing, interpreting, protecting, and transmitting critical information about the war that facilitated anti-submarine warfare, battlefield strategies, and medical treatment.

Looking back, the yeomen (F.) enriched and extended women’s legacy of naval service. While they may not have called themselves pioneers, they paved the way for those who followed them.

The next chapter considers what female yeomen’s naval service meant to them, how the war changed their lives, their post-war challenges, and their efforts to preserve their history.

Regina T. Akers, Ph.D., "Chapter 3: Reporting to Work," in The Navy’s First Enlisted Women, Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, 2019.