USN First Enlisted Women: Setting the Stage - 2019

This chapter provides some essential context for the history of the Navy’s first enlisted women. It highlights the sharp contrasts between the country’s founding principles, democratic values and justification for war, and the treatment of women and African Americans.

War Department policies reflected the accepted societal standards and expectations for both groups. Women and African Americans endured legal discrimination practiced by law, custom, and tradition with no expectation of protection or justice.

Large segments of society treated both groups as second-class citizens. This treatment contradicted the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution that stated that no state can make or enforce laws that limit the privileges of citizens of the United States.

The Fifteenth Amendment granted American citizens the right to vote, however, women and blacks could not do so in 1914.

The chapter also provides an overview of the two group’s impressive record of participation and support during wars, conflicts, and crises and considers how the experiences of the nation’s leaders influenced their policies and programs.

Societal standards required women to be chaste, discreet, and, if married, submissive to their husbands. They were thought to be delicate, weaker than men, and dependent on them.

Parents prioritized sending their sons to college instead of their daughters whose primary roles were to become mothers, wives, and home makers.

Many women had their own agenda during the Progressive Era (1900–1920). They were part of the international suffrage movement as well as the anti-war and temperance campaigns.

The women’s club movement provided self-help and funding for various causes. No strangers to controversy, they supported the efforts to end child labor, to improve safety and working conditions in factories, and to grant women control over their bodies (i.e., using birth-control methods).

Several women leaders emerged during this period including Nannie Helen Burroughs, an African American educator and suffragist; Margaret Sanger, leader of the birth control movement; Mary Ritter Beard, author and member of the Women’s Trade Union League; Madam C. J. Walker and Maggie Lena Walker, African American entrepreneurs; and Jane Addams, pacifist, social worker, and founder of the Hull House.

The Navy allowed women to enlist for service before the United States entered the Great War. During any national crisis dating back to 1775, women continued their legacy of volunteering their service—despite their social status and discrimination.

During the American Revolution, women supported the colonial forces on and off the battlefield by maintaining the home front, nursing the wounded, and sponging out cannons between shots.

Women boycotted British goods and made bandages. During the American Civil War, the government hired women en masse to meet the labor needs.

They led the U.S. Sanitation Commission, the American Red Cross and other critical organizations.

Women also dressed in disguise to enlist and others accompanied military units. Deborah Sampson disguised herself as a man to fight as Robert Shurtleff with the 4th Massachusetts Regiment. She earned an honorable discharge and her husband received her pension posthumously.

Hiding her gender, Sarah Emma Edmonds served as a soldier in the Union army. Susie King Taylor distinguished herself as a scout and raider with the 33rd United States Colored Troops, and Harriet Tubman led Union troops in combat. In 1862, four African American nuns, Sisters of the Holy Cross, Alice Kennedy, Sarah Kino, Ellen Campbell, and Betsy Young were among the 12 nuns who assisted the sick aboard USS Red Rover, the Navy’s first hospital ship.

Ann Bradford (1830–1903), born a slave in Rutherford, County, TN, reported for service as a contraband aboard USS Red Rover in January 1863. She enlisted as a first class boy to support the nurses.

She married Gilbert Stokes in 1864 and lived in Belknap, Illinois until his death in 1866. After becoming literate, she received a $12.00 monthly pension for her service in 1890.

Women also worked as spies, seamstresses, and couriers.

Dr. Margaret Walker, a contract Army surgeon was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. After the war, William Catha bravely fought in disguise with the 38th United States Colored Infantry Regiment, Buffalo Soldiers until a doctor discovered her gender during an illness.

The government contracted women nurses during the SpanishAmerican War, but they did not become an official part of the military until Congress created the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and the Navy Nurse Corps seven years later. Thus, in 1914 nurses were the only women in the U.S. armed forces.

The military expanded its recruitment and utilization of women during the first World War out of necessity. This decision met opposition from those believing that a woman’s place was in the home. Others questioned the judgement of any woman desiring to serve in the armed forces—given the reputation of some uniformed men. Women were not considered equal to men and did not receive equal wages for equal work in civilian jobs.

World War I started with the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and his wife in Sarajevo by a Serbian nationalist on 28 June 1914.

One month later Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, which had a protective alliance with Russia. German support for AustriaHungary put most of Europe into conflict immediately after the assassination.

The Triple Entente of France, the United Kingdom, and Russia fought against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria.

In an attempt to preempt a two-front war, Germany invaded France through Belgium, which had a treaty with the United Kingdom drawing Britain into the war. Modern weaponry paired with outdated tactics and static trench warfare resulted in deadly consequences. Soldiers shared their trenches with lice, rats, and mud.

As in previous wars and conflicts, no one returned home unchanged. The sights and sounds of war left many veterans with permanent disabilities such as dismemberment, hearing loss, blindness, lung conditions due to gas exposure, and shell shock.

The tremendous casualties and strains on manufacturing suffered by the Allies made victory over the Central Powers uncertain without the United States’ participation.

General John J. Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Force, led over 600,000 soldiers supporting the Allies. He estimated that three million soldiers would be needed to stop the German advance, protect resources and railways, train in theater and build docks, hospitals, bridges, telephone nets and other critical infrastructure.

American soldiers, as well as Marines and Coast Guard members distinguished themselves in several campaigns including Oise-Aisne, Soissons, Chemins des Dames, and Verdun. In the Atlantic, the U.S. Navy escorted convoys and fought German U-boats.

It is ironic that such a catastrophic world war ended what is known as the “Progressive Era.” Another paradox is the fact that progressive President Thomas Woodrow Wilson, the man who led the United States through the war and was a champion for social reform, free trade, and democratic liberty allowed discrimination against blacks and women to continue.

The United States’ leaders’ beliefs about these societal groups influenced their decision-making processes and policies. Wilson, a former president of Princeton University, and governor of New Jersey was a progressive Democrat committed to domestic reform.

He was born in Staunton, Virginia on 28 December 1856, to Reverend Doctor Ruggles Wilson who established the Southern Presbyterian Church and Janet Woodrow Wilson.

He witnessed the country’s struggle to unify following the Civil War and the separation of the blacks and whites by law, custom, and practice after Congress abolished slavery. Wilson graduated from Princeton University in 1879 and the University of Virginia law school in 1880.

After earning his doctoral degree at the Johns Hopkins University in 1886, he taught at Bryn Mawr College, Wesleyan University and Princeton University. As an isolationist he had no desire to enter “their war” or “the war over there.” Historian Robert Love noted that Wilson’s approach to foreign policy was based on “a Calvinist conception of international morality.”

Wilson adhered to a policy of neutrality and reluctantly agreed to incremental involvement by way of sending Britain and France much needed supplies and escorting their ships to assure safe passage. He ran for his second term on the promise to keep the nation out of the war.

President Woodrow Wilson Waves His Top Hat from the Deck of USS George Washington (ID No. 3018), as She Steamed up New York Harbor upon the President’s Return to the United States from the World War I Peace Conference in France, 8 July 1919. NHHC photograph, Washington Navy Yard (WNY), Washington, DC, NH 18. GGA Image ID # 191a707ff6

Wilson argued that “every reform we have won will be lost if we go into this war.”10 Events changed his mind. When a German submarine sank the British liner RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915, 201 passengers, including 159 Americans died.

The unprovoked sinking of unarmed ships continued (i.e., the British liner Arabic on 19 August 1915). Germany periodically agreed not to attack unarmed passenger ships, but merchant ships remained its navy’s targets.

It was principally the German submarines patrolling the U.S. Atlantic coast, the unrestricted submarine warfare against Allied ships, and the intercepted Zimmermann Telegram— in which a German foreign secretary proposed an alliance between Germany and Mexico in the event that the United States entered the war—that led Wilson to seek Congressional declaration of war against Germany.

Congress declared war against Germany following Wilson’s 2 April 1917 address proclaiming that it was a war to make the world safe for democracy, to protect human rights, to end the German military threat, and to assure freedom of the seas.

He noted, “There is not a single selfish element, so far as I can see, in the cause we are fighting for. We are fighting for what we believe and wish to be the rights of mankind and for the future peace and security of the world.”

He reminded Americans that everyone on the battlefield and at home had a contribution to make to the war effort. Within days of the declaration of war, Congress began passing key legislation.

The Selective Service Act, for example required all males from 21 to 30 years of age to register for military service. In an effort to control the flow of information about the war and to assure the emphasis on the U.S. war’s aims, the President started the Committee on Public Information.

The cabinet members who Wilson appointed to lead the Departments of War and Navy were essential to United States’ successful prosecution of war against the Central Powers.

Edward M. House, a businessman and one of Wilson’s closest advisors, recommended Josephus Daniels, a native of North Carolina and career newspaper businessman, for the position of Secretary of the Navy when the President selected his first cabinet.

Daniels who shared similar interests with Wilson as a democrat, a progressive, a pacifist and a segregationist, became the longest serving Secretary of the Navy since Gideon Wells during the Civil War.

Despite his lack of experience with the Navy and anti-war beliefs, he set forth significant reforms, the least of which were improving naval training and anti-submarine warfare doctrine, and suspending the distribution of alcohol at naval commands at sea and ashore.

He launched naval aviation and deployed gunboats and Marines to Mexico, Panama, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic. Under his direction, millions of American soldiers on Navy-escorted transports arrived safely in the European theater.

Also, betterquality mine detection and destruction techniques, and ship performance were developed during his tenure. He required the Naval Academy to admit Sailors from the fleet for the first time and that every naval base and ship have an academic department.

Daniels seized German ships in U.S. ports, refurbished them, and used them as troop transports. The Vaterland renamed Leviathan delivered 96,804 troops and the Hamburg renamed Powhatan transported 14,613.13

Josephus Daniels Served as Secretary of the Navy during Woodrow Wilson’s Presidency. He Was in Office from 5 March 1913 to 5 March 1921. NHHC photograph, NH 2336. GGA Image ID # 191a9c022f

When Secretary Daniels offered Franklin D. Roosevelt the job as his Assistant Secretary of the Navy, the young FDR replied, “It would please me better than anything else in the world.

All of my life I have loved ships and been a student of the Navy, and the Assistant Secretary is one place, above all others I would love to hold.”

Roosevelt had known the sea from a young age and had crossed the Atlantic 20 times. He maintained a collection of ship models, artwork, and a large maritime library.

This Harvard trained lawyer saw this position as a key professional step in his ascension to the Presidency of the United States. Daniels and Roosevelt had support.

Congress established the Chief of Naval Operations position in 1915 and Daniels selected Rear Admiral William S. Benson to fill it. Benson, a Georgia native and, an 1877 Naval Academy graduate (and an Anglophobe) was the commandant of the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

His sea commands included the cruiser Albany and battleship Utah. According to author William N. Still, Benson, “sought to prepare the navy for war, but the novelty of his position and pacifism of the naval secretary limited his activity.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, April 1917. NHHC photograph, NH 50868. GGA Image ID # 191aaf9fc0

Daniels sent Rear Admiral William S. Sims, President of the Naval War College and an 1876 Naval Academy graduate, to London as his liaison with the British Navy. Daniels told Sims, You have been selected for this mission not because of your Guildhall speech but in spite of it.

If the time ever comes when the British Empire is seriously menaced by an external enemy, it is my opinion that you may count upon every man, every dollar, every drop of blood of your kindred across the sea.16 Daniels instructed Sims to travel in civilian attire and to keep him and CNO Benson informed.

Benson reminded Sims that the British and the Americans had different goals. Wilson made the situation worse when he told Sims to send strategy and policy reports directly to him.

Sims’s first report of 14 April 1917, indicated that the German submarines were more successful than initially thought and that Germany threatened Allied supplies, communications, and control of the seas.

First Sea Lord Admiral John R. Jellicoe warned Sims that “[t]hey [the Germans] will win, unless we can stop these losses—and stop them soon.”17 Wilson and Daniels did not believe the situation to be as critical as described. Sims proved a harsh opponent of Daniels openly expressing his disagreements with his strategy and leadership.

Manning the United States Navy

The Navy had 342 ships and 79,182 officer and enlisted personnel in 1917. There were points during the war when recruiters could not meet their goals.

The need was so urgent that Sailors recently graduated from basic training reported to the war zones without the benefit of advanced training and the duration of boot camp was shortened.

The new graduates often replaced more experienced personnel needed to work on the newer ships. Commanding officers complained about their crews’ inexperience and frequent turnover.

They opposed the idea of having the “green crews” complete their training aboard ship. The quality of life on a ship varied depending on the type of vessel.

The crews typically endured over-crowding, sea sickness, repeated drills, limited amenities, severe temperatures, and leaking ships.

The coal heavers or the “black gang” as they were called due to the coal covering their skin worked in the bottom of the ship in one hundred degrees without ventilation.

Crews faced the dangers of enemy attacks, heavy seas, and violent storms. The mess depended on the availability of refrigeration, the length of the trip, the size of the ship, the freshness of the food supply, and the ability of the cook.

Despite the desperate need for manpower, Daniels did not make maximum use of all available personnel. His progressivism did not extend to blacks.

Naval policy limited blacks to service in specific ratings primarily as messman or steward and to the enlisted ranks.

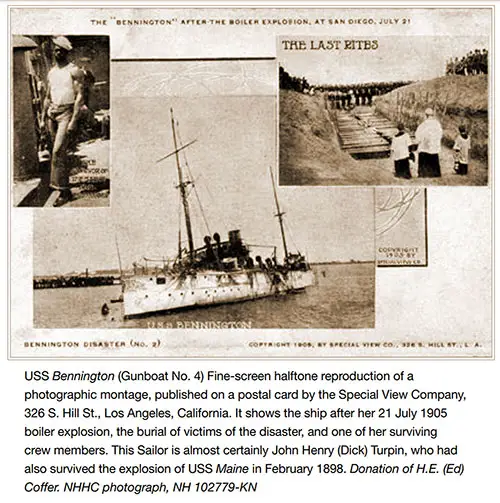

Mess Attendant John Henry Turpin survived the explosion aboard the battleship USS Maine in Havana Harbor on 14 February 1898, and a boiler blast aboard USS Bennington Gunboat #4 on 21 July 1905. Though he became one of the Navy’s first black chief petty officers as a gunner’s mate in 1917, he was one of the few exceptions.

USS Bennington (Gunboat No. 4) Fine-screen Halftone Reproduction of a Photographic Montage, Published on a Postal Card by the Special View Company, 326 S. Hill St., Los Angeles, California. It Shows the Ship after Her 21 July 1905 Boiler Explosion, the Burial of Victims of the Disaster, and One of Her Surviving Crew Members. This Sailor Is Almost Certainly John Henry (Dick) Turpin, Who Had Also Survived the Explosion of USS Maine in February 1898. Donation of H.E. (Ed) Coffer. NHHC photograph, NH 102779-KN. GGA Image ID # 191ab5ed92

Such discrimination did not lessen the African American’s desire to enlist. There were 5,328 blacks among the Navy’s 435,398 Sailors in 1918.20 They fought to maintain a democracy that did not grant them their democratic and constitutional rights.

Daniel’s policy was consistent with Secretary of War Newton D. Baker who commented on the participation of blacks in the armed forces on 30 November 1917:

As you know it has been my policy to discourage discrimination against any persons by reason of race. This policy is adopted not merely as an act of justice to all races that go to make up the American people, but also to safeguard the very institutions which were now at the greatest sacrifice engaged in defending and which any racial disorders must endanger. At the same time there is no intention on the part of the War Department to undertake at this time the so-called race question.

Women Answer the Government’s Call

Once again women responded to the call to action. They filled jobs left vacant by men serving in the military, and maintained the home front. They staffed canteens, grew food, and sold liberty bonds. Red Cross nurses worked at home and in the war theater. The “hello girls” speaking fluent French operated the U.S. Army Signal Corps switchboards overseas.

The military also relied on women to alleviate their personnel shortages. Army and Navy nurses treated patients at home and abroad. For the first time, the Navy, the Marine Corps, and the Coast Guard enlisted women. The next chapter explains Secretary of the Navy Daniels’s decision to enlist women, the recruitment program, their motives for joining, the enlistment process, and their benefits.

Regina T. Akers, Ph.D., "Chapter 1: Setting the Stage," in The Navy’s First Enlisted Women, Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, 2019.