USN First Enlisted Women: “Women Join the Navy”

Over 11,000 women from every state, American territory, and the District of Columbia volunteered to enlist into the United States Navy to free male Sailors for combat duties.

These women courageously performed primarily clerical work with little if any knowledge of the Navy, how it functioned, and where they might be assigned. Like the men they replaced, they willingly exchanged their lifestyles and freedoms for naval policies and procedures.

In the face of many challenges and criticism they remained unwavering in their support of the Allies’ efforts to defeat their enemies and to bring their loved ones home sooner.

Although the Navy provided no basic training, they assumed their duties and often proved more productive and effective than the men they freed for combat.

After working 10- or 12-hour days, they endured classes to master basic naval policies, practices, and regulations.

This chapter describes the Navy’s need to enlist women, their reasons for enlisting, as well as the Navy’s recruitment efforts, enlistment process, and training for its newest reservists.

The Navy’s First Enlisted Women

In addition to assuring the best deployment of naval ships, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels required personnel to support the war effort at home.

In 1917, the Navy had 128,666 regular enlisted personnel.23 When the Civil Service Commission reported its inability to provide the number of personnel required to meet the Navy’s need for clerical workers, Secretary Daniels explored his options.

When he learned that there was no legal reason why women could not be enlisted, he changed the Navy forever. For the first time, women joined the ranks of its enlisted men.

The yeomen (F.) and the Navy nurses in World War I paved the way for the women in today’s Navy. More than one person claims to have been the first to propose the recruitment of women to Daniels.

Lieutenant Commander Frederick Payne, a recruiter in Philadelphia, suggested that women enlistments would persuade more men to join.

Representatives John J. Eagan (D-NJ), Fred L. Blackmon (D-AL), and other members of Congress also approached Daniels about this.

Charlotte Louise Berry Winters, a native of Washington, DC, stated that she discussed women’s rights to enlist with Daniels in 1916.

The Naval Appropriations Act of 1916 (Public Law 241) established the United States Naval Reserve Force, which was composed of six classes: Fleet Reserve, Naval Reserve, Naval Auxiliary Reserve, Naval Coastal Defense Reserve, Volunteer Navy Reserve, and the Naval Reserve Flying Corps.

The act stated that any United States citizen could serve, requiring four-year enlistments, and taking the oath of enlistment. Daniels admitted women into Class 4, the Naval Coastal Defense Reserve, which allowed for the first enlistment of officers and enlisted personnel, because it had the budget to pay for the new reservists.

On 19 March 1917, Rear Admiral Leigh C. Palmer, the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, which was the personnel branch in the Navy Department, issued a memo to the naval districts announcing the women would be enlisted “in the ratings of Yeoman, Electrician (Radio), or in such other ratings as the commandant may consider essential to the District organization.” Eventually, 11,000 enlisted women served along with 1,713 nurses, 269 enlisted female Marines, and 2 enlisted women in the Coast Guard.

Women’s Motivations

Women of various ages and cultural backgrounds made inquiries about service in the Naval Reserve before the official announcement. In addition to patriotism, their interest stemmed from the Navy providing equal pay for equal work based on rank and regular employment.

Like the male Sailors, their service helped to bring their loved ones home sooner and to help the country defeat the Germans. Some women joined to honor their relatives and friends who had been killed or wounded.

Another motive was joining with a relative. Sisters Ethel Trussler Fahey and Fannie served at the P&C Depot in New York; five of their relatives also joined the military.

Some women were so excited that they enlisted before age 18. Thelma Franklin’s screening failed to discover that she was 14 years of age. Chief Yeoman Helen Harper, a Canadian native assigned to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Washington, DC, was the first female reservists naturalized into the United States.

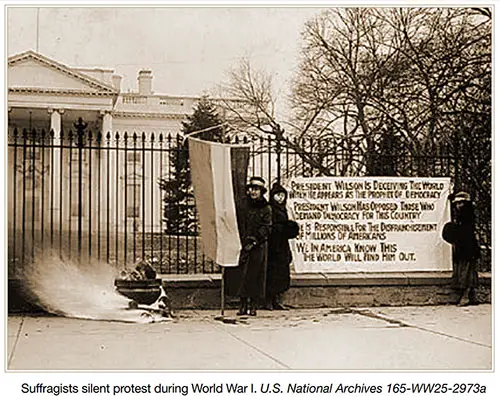

Suffragists Silent Protest during World War I. U.S. National Archives 165-WW25-2973a. | GGA Image ID # 191aba12a8

Some women were drawn by doing something different or continuing their family’s legacy of military service.29 They also thought enlisting might persuade the President and Congress to support the proposed 19th Amendment to the Constitution granting women the right to vote. Suffragettes met in the homes of future female yeomen such as Joy Bright Hancock.

Recruitment Efforts

Women were not drafted. Like the nurses, they volunteered. Naval service was one of several means of supporting the war. Thus, the Navy had to compete for the attention of 18- to 35-year-old American women whose options included the National League for Women’s Services, the Women’s Council on Defense, the American Red Cross, the Women’s Land Army, and factory jobs.

Applicants had to be United States citizens, be physically and mentally fit, take the oath of enlistment, and agree to serve for four years wherever the Navy stationed them.

The Navy placed recruitment ads in national and regional newspapers including the Washington Post, the Baltimore Sun, the Chicago Tribune, and on the radio. One of the more popular posters read “If I were a man I would enlist.”

Answering Daniels’s Call

Loretta Perfectus Walsh, a native of Olyphant, Pennsylvania, and a graduate of the Lackawanna Business School in Scranton, distinguished herself as the first woman to enlist. When she joined, Loretta was employed as a civilian clerk at a Navy recruiting station in Philadelphia. She was motivated by her family history of military service and her love for her country.

Word of mouth also proved effective. When Frieda Greene’s father mentioned the announcement at their dinner table, she remarked, “That’s for me.”

Another recruit came to Washington, DC, for a civilian job. Her parents were so concerned about their daughter being in “a dangerous place for a girl” that they insisted she live outside of the city with a cousin and her father arranged for a Navy ensign to meet her at the train station.

After the ensign asked her why she had not considered enlisting, she applied. Phyllis Kelley was employed as the secretary to the Dodge Brothers Motor Company in Boston when she heard that she could apply at the Naval Reserve in the Boston Navy Yard.

Kelley began her enlistment process on her lunch hour. Margaret Mary Fitzgerald King of Stevens Point, Wisconsin, the daughter of a U.S. Army major, had a civil service job during her father’s tour in the Philippines.

She enlisted in the Navy on 7 June 1918, in Portland, Oregon, with Len Butzer Reynolds.

Gertrude Edna Murray was working at the Globe Wernicke Company when someone called from the Fleet Supply Base across the street in south Brooklyn in desperate need of a file clerk. Murray responded to their call and went on to manage 40 female yeomen as a chief yeoman at that base.

Lou McPherson Guthrie and two friends applied when the Navy appealed for 100 women war workers to reduce the shortage of accounting workers in the Navy Yard. Guthrie considered government work when her seventh-grade teaching position at a North Carolina school ended.

After getting 95 percent of the questions in the math section of the civil service examination correct, she accepted a job with the Bureau of War Risk Insurance in the Smithsonian Institution building in the nation’s capital.

She welcomed the annual salary of $1,000. When she discovered that the YWCA could not accommodate her, she decided to live in one of the homes open to women workers.

Secretary Daniels, cabinet members, and others helped to alleviate the housing shortage by hosting civilian and military personnel assigned to Washington, DC.

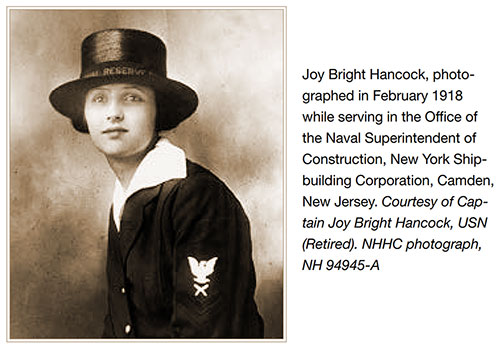

Joy Bright Hancock relieved a man for duty in the Pennsylvania National Guard when she assumed his job as statistician. Captain Elmer Wood, recalled to active duty, commanded the Branch Hydrographic Office of the Navy in Philadelphia.

He had known Hancock since her childhood. He supported her effort to join by introducing her to Captain George Cooper, assigned to the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Cooper directed her to the Naval Home to start the process.

Joy Bright Hancock, Photographed in February 1918 While Serving in the Office of the Naval Superintendent of Construction, New York Shipbuilding Corporation, Camden, New Jersey. Courtesy of Captain Joy Bright Hancock, USN (Retired). NHHC photograph, NH 94945-A. | GGA Image ID # 191adb26e9

Helen O’Shaughnessy and Bell V. Dunn distinguished themselves as the first women to enlist in Charleston, South Carolina and aboard USS Hartford, the former flagship of Admiral David G. Farragut.

Multiple sisters from one family enlisted as did a few mother-daughter pairs, along with the daughters of cabinet officers, members of Congress, and naval officers.

The female yeomen represented every state. The highest number of them came from New York at 2,329, Massachusetts at 1,324, and Virginia at 1,071.

Many of these pioneers were working in related fields.

Charlotte Louise Berry Winters, a native of Washington, DC, learned about an opportunity to serve as a yeoman (F.) after she graduated from the Washington Business High School.

She was among the first women to enlist and spent the war as a clerk in the Naval Gun Factory at the Washington Navy Yard. When Winters died in 2007, she was believed to be the last surviving female World War I veteran.

Elizabeth Kirk Stewart and Elizabeth Townson Campbell, both DC natives, enlisted on 24 March 1917, and were the first applicants to get their physical exams at the Naval Hospital at 23rd and E Streets, N.W., and the first enlisted women assigned to the Naval Gun Factory.

There were 14 African Americans—DC, Texas, Mississippi, and Maryland natives—among the 1,874 enlisted women assigned to naval facilities in Washington, DC.

Opposition to Enlisting Women

Everyone did not welcome the patriotism of female enlistees. Parents’ beliefs about Sailors’ behavior and character made them reluctant to support their daughters’ decision.

Male Sailors were skeptical about women’s contributions and feared they would disrupt their work space and reduce efficiency.

Individuals expressed the argument that women did not belong in “their service” in newspapers. Yeoman (F.) Lou MacPherson Guthrie recalled reading a retired colonel’s editorial that noted, “Preposterous! First women wanted to vote.

Then Alice Roosevelt started them smoking cigarettes! Now they’re talking about being soldiers. Next thing we know they’ll be cutting off their hair and wearing pants!”

Eunice C. Dessez observed, “Old-time sailors of the day were somewhat scandalized and nonplussed by the thought that WOMEN would wear the same uniform as themselves.”

Yeoman (F.) Lillian Budd recalled an older Sailor telling her that he would immediately request sea duty instead of serving with her. Another Sailor proclaimed he would rather serve in China than work with women.

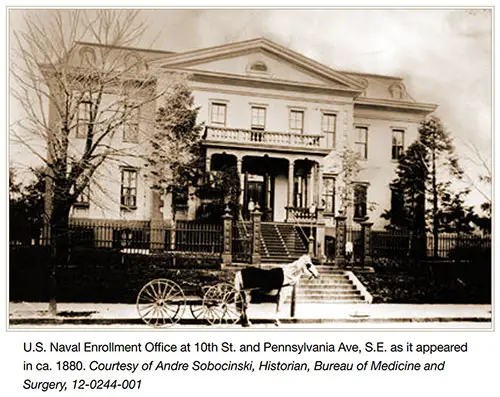

U.S. Naval Enrollment Office at 10th St. and Pennsylvania Ave, S.E. as It Appeared in ca. 1880. Courtesy of Andre Sobocinski, Historian, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 12-0244-001. GGA Image ID # 191b41c1d9

Lieutenant Charles H. Venable, USN, recalled to active service on 19 February 1917, commanded the United States Naval Reserve Enrollment Office at 10th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, S.E., in Washington, DC.

His staff included Eunice C. Dessez and other Yeomen (F.), two Navy nurses, and one civilian, a Mr. J. A. Dawkins. They worked ten-hour days and averaged 640 enrollments between March and September of 1918.

September 1917 and August 1918 marked the lowest and highest numbers of enlistments, respectively 17 and 1,077. The officers and men of the land-based naval railway gun batteries under Rear Admiral C. P. Plunkett, USN, were among their notable enlistees.

Mr. Steve T. Early, a journalist who later served as the third White House press secretary and for a few months in the Truman Administration, sent Irene Manning of Washington, DC, with his letter of endorsement, to this enrollment office. Lieutenant Venable promptly enrolled her on 31 March 1917.

The Process of Joining the Navy

Enlistment was not a complicated process. Applicants completed an interview and a written exam often at the recruiting station. Those with clerical experience took a typing or stenographer test.

They were also required to be physically fit like their male counterparts. However, the logistics of the enlistment process were not initially in place.

Navy nurses performed some of the preliminary exams to ensure the potential enlistees’ eligibility for service, but Navy doctors conducted most of them.

This created some uncomfortable situations. After Lillian Budd told the staff at the recruiting station she wanted to join the Navy, the doctor immediately instructed her to remove her clothes.

She recalled being horrified, but not deterred. After a naval medical officer completed his assessment and she passed a shorthand test, she took her enlistment oath and began her naval service as a yeoman first class.

Estelle Kemper recalled the women recruits having to stand along a hallway in towels waiting to see the doctor. This embarrassed some and made others fearful.

A fellow recruit exclaimed to Kemper, “You act like you didn’t mind having no clothes on!” Trying to calm her down, Kemper assured her that the doctors were used to seeing nudity and added, “Oh, after the first couple of times you get used to this sort of thing.”

The woman misunderstood her statement and Kemper tried to reassure her that the doctor was so focused on his job that no one had anything to fear.

Having met all the requirements, the Navy’s newest members took the same oath as male Sailors:

I, _____ do solemnly swear that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the United States of America, and that I will serve them honestly and faithfully against all enemies whomsoever; and that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to the Rules and Articles of the Government of the Navy.

After receiving their identification card, most returned home until the Navy issued their orders. If the new reservists had an urgently needed skill set, they often reported for duty the same day.

Salary and Benefits

Their pay was based on their rank. A yeoman (F.) earned $28.75 per month with a 20-cent deduction for hospitalization. Since the Navy did not provide housing or messing, the women also received $1.25 per day for subsistence pay and an annual $60.00 clothing allowance.

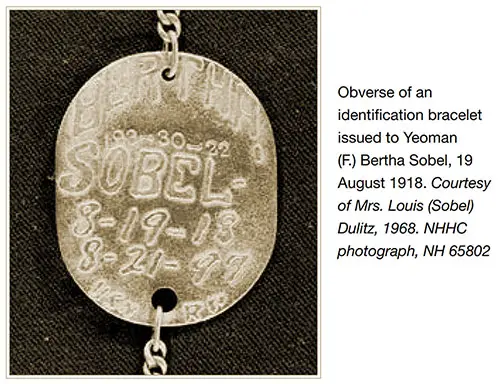

The Bureau of Navigation began issuing identification tags—or “dog tags”—to yeomen (F.) from the new Navy building in accordance with General Order No. 294.48 An identification bracelet was also worn.

The Obverse of an Identification Bracelet Issued to Yeoman (f.) Bertha Sobel, 19 August 1918. Courtesy of Mrs. Louis (Sobel) Dulitz, 1968. NHHC photograph, NH 65802. GGA Image ID # 191b55867d

Working Out a Few Administrative Issues

Enlisted women in the Navy raised new administrative problems. For the first time, the Navy had to document a Sailor’s gender. The Bureau of Navigation automatically assigned new Sailors to ships.

When the women received orders to ships, they were ascribed to barges and other sunken naval property. It did not take long before people starting calling the women by nicknames such as “yeomenettes” and “yeowomen.”

Rear Admiral Samuel McGowen, the paymaster of the Navy, objected, stating, “These women are as much a part of the Navy as the men who have enlisted.

They do the same work . . . and have done yeoman service.” Thus, naval officials designated the women the rating of “Yeoman (F.),” the “F” denoting female to distinguish them from males.

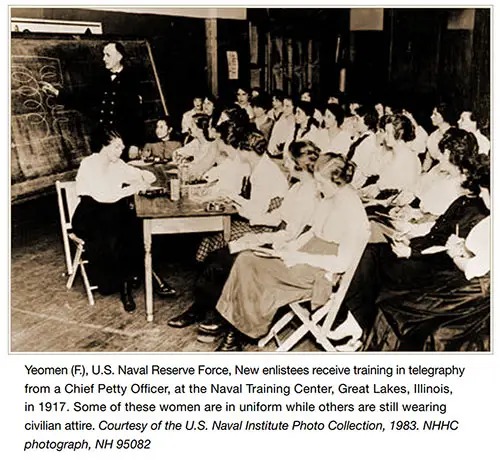

Training

Just as the Navy did not plan for assessing their physical fitness, there were no preparations for their training, housing, or uniforms. Their enlistment rating and rank depended on a recruit’s experience.

Most enlisted as yeoman, master-at-arms, or mess attendant third class. A small number entered the Navy as chief yeoman. Typically, training happened on the job and from reading the Bluejacket’s Manual and mimeographed naval regulations.

They learned close order drill on the National Mall after duty hours. Without the benefit of basic training, they had to take classes designed for them at 7:00 pm at the enrollment office at 10th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, S.E. The Navy discontinued the night school on 3 October 1918.

Yeomen (f.), US Naval Reserve Force, New Enlistees Receive Training in Telegraphy from a Chief Petty Officer, at the Naval Training Center, Great Lakes, Illinois, in 1917. Some of These Women Are in Uniform While Others Are Still Wearing Civilian Attire. Courtesy of the U.S. Naval Institute Photo Collection, 1983. NHHC photograph, NH 95082. GGA Image ID # 191b5f3ada

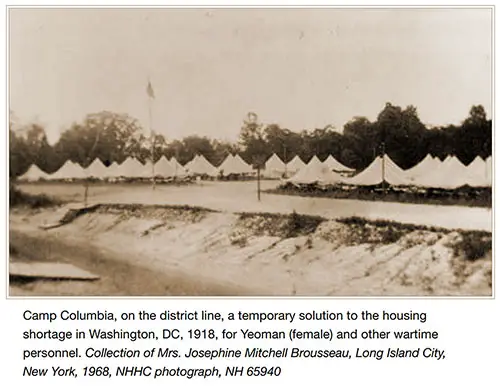

Housing

The Navy’s barracks were filled, eliminating that option for the Yeomen (F.). Some could supplement their benefits by renting a house, but that was not the norm.

The YWCA and private homes helped to alleviate the housing shortage, but Washington simply lacked the capacity to host all the civilian and military people working in the nation’s war headquarters.

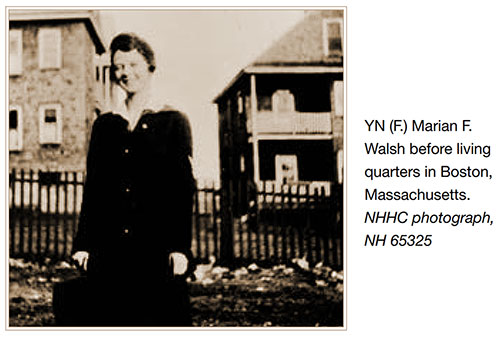

Ann Ginter De La Fountaine of Pacheco, California, assigned to the Medical Department at Mare Island, was among the exceptions. She and the other yeomen (F.) lived in a refurbished Marine Corps barracks and commuted to work riding a two-car train nicknamed the “Powder Puff Special.” Marion F. Walsh Driscoll also had quarters.

Camp Columbia, on the District Line, a Temporary Solution to the Housing Shortage in Washington, DC, 1918, for Yeoman (female) and Other Wartime Personnel. Collection of Mrs. Josephine Mitchell Brousseau, Long Island City, New York, 1968, NHHC photograph, NH 65940. GGA Image ID # 191b745814

YN (F.) Marian F. Walsh before Living Quarters in Boston, Massachusetts. NHHC photograph, NH 65325. GGA Image ID # 191b9a9c09

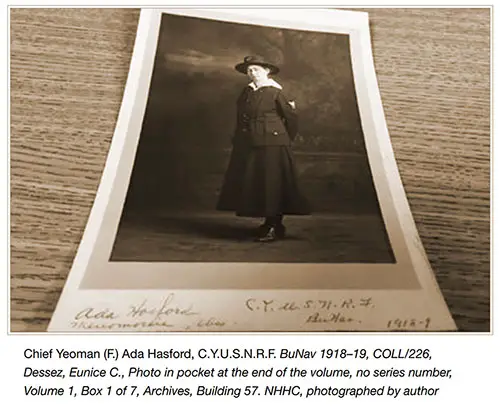

The Enlisted Women’s Uniform

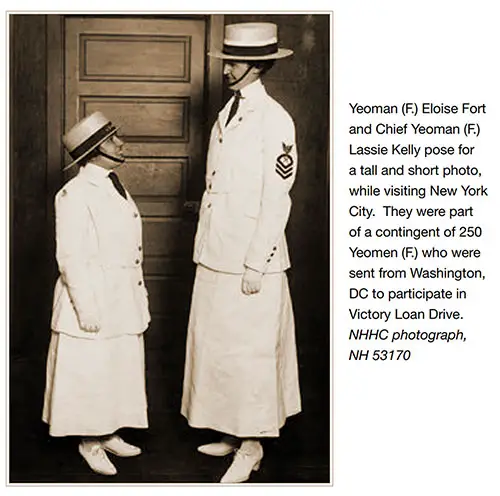

The female yeomen reported for duty in their civilian attire because the Navy did not initially provide them with uniforms. They eventually received their Norfolk-style jacket that they wore with a dark skirt.

Navy uniform regulations followed, but the respective commanding officers had final approval. The Navy’s failure to designate one cover (hat) for the yeomen (F.) is evidenced in the photos depicting the wide variety of headgear.

Their covers, however, had to have wide brims to cover their hair buns, which were kept in place with threeinch hairpins. Yeomen (F.) in factories processing munitions wore overalls.

There were complaints that the heavy cape added to the female uniform was only comfortable during the coldest weather.

Chief Yeoman (F.) Ada Hasford, C.Y.U.S.N.R.F. BuNav 1918–19, COLL/226, Dessez, Eunice C., Photo in Pocket at the End of the Volume, No Series Number, Volume 1, Box 1 of 7, Archives, Building 57. NHHC, Photographed by Author. GGA Image ID # 191bd84c4f

Esther Kemper disliked the uniform because [t]he skirts were straight, tight, and the most awkward length possible. The jackets were shapeless affairs, loosely belted in a sort of ‘Norfolk’ attempt. The entire ensemble turned out to be as flattering to the female form as our father’s business suits would have been. . . . Normally we were not a badlooking lot. In those uniforms we could have been outdone in looks by the Salvation Army. Well, we were a crestfallen crew—almost a tearful one. We did love our country, and did want to do our duty by the Navy, but how on earth could any country demand such a sacrifice?

Yeoman (F.) Eloise Fort and Chief Yeoman (F.) Lassie Kelly Pose for a Tall and Short Photo While Visiting New York City. They Were Part of a Contingent of 250 Yeomen (f.) Who Were Sent from Washington, DC to Participate in Victory Loan Drive. NHHC photograph, NH 53170. GGA Image ID # 191bf31f36

Earl Goodwin, known as “the Dean of Washington Correspondence” and married to Elizabeth Cromelin, part of the Yeoman (F.) battalion remarked,

As for him who sneered at the uniform of these women I would almost believe him perverted mentally. The yeoman (F) uniform is the uniform of the United States, and to have worn it in war time is the greatest service any American can perform. Whether the wearer is a man or a woman—the honor is greater than anything else I know, except the honor of dying for the country in that uniform. So if by chance anyone forgets himself far enough to sneer at the yeoman (F) uniform, let the finger of scorn be pointed at HIM—not the uniform.

The yeomen (F.) remained committed despite the Navy’s failure to establish a training program for them before starting their active duty service.

Their patriotism was not deterred by the administrative and logistical challenges or the hostile opposition they endured. The next chapter focuses on how their diverse and multiple contributions as Yeomen (F.) contributed to the Allied war machine, gender relations on the job, and the work-related difficulties they faced.

Various profiles will show how their jobs gave them a front-row seat to the war effort and naval advancements during the war. Their work also gave them direct access to the President, cabinet members, and senior naval leaders.

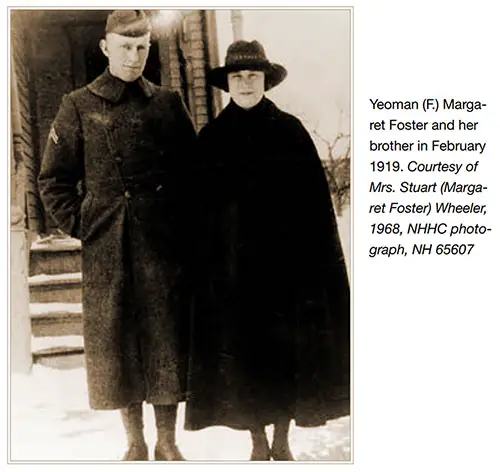

Yeoman (f.) Margaret Foster and Her Brother in February 1919. Courtesy of Mrs. Stuart (Margaret Foster) Wheeler, 1968, NHHC photograph, NH 65607. GGA Image ID # 191c924d57

Regina T. Akers, Ph.D., "Chapter 2: Women Join the Navy," in The Navy’s First Enlisted Women, Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, 2019.