USN First Enlisted Women: “Changing the World, Their Lives, and the Navy”

Female Yeoman on Submarine K5, SS-36, Gazing Through Her Binoculars circa 1918. National Archives & Records Administration, NARA ID # 80G1025873. GGA Image ID # 1982439333

“I thought I was doing something for my country—I can see now how much more my country has done for me.”90 YNC Lillian Budd, USNRF

The yeomen (F.) proved their worth many times over and received wellearned accolades for their work from President Woodrow Wilson and others. The quality of their work, their productivity, and their overall contributions to the Navy’s war effort persuaded leaders to invite them to continue their duties as civilian employees.

Despite their invaluable service, yeomen (F.) had to fight for the rights and benefits they deserved. Post-war developments mirrored pre-war beliefs about military women and a lack of respect for them.

Though they had not enlisted for long, most enjoyed the experience and had mixed feelings about leaving the Navy. They established the National Yeoman (F.) Association in 1926 to preserve their history. This chapter shows how the Great War forever changed the world, the yeomen (F.), and the Navy.

The War Ends

The United States’ raw materials, manpower, supplies, and military forces gave the struggling Allied nations victory over Germany and the Central Powers.

Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany resigned on 9 November 1918, and, two days later, Germany signed the surrender documents in a railroad car near Compiègne, France, ending the first global war.

From that time forward, that date has been known as Armistice Day. Victory had come at a steep cost. The combined Allied and Central Powers’ casualties included 8.3 million killed and 21.3 million wounded. The war caused unprecedented physical damage in Europe.

However, the Great War also saw the introduction of many innovations, including military aviation, advanced medical treatments, and the first time women formally enlisted in the U.S. military.

Victory also inspired hope for the future and that the triumph of democracies over authoritarianism would lead to a brighter future for all.

President Wilson’s 1918 Thanksgiving Proclamation read in part, “My Fellow Countrymen: The Armistice was signed this morning. Everything for which America fought has been accomplished. It will now be our unfortunate duty to assist by example, by sober, friendly counsel and by material aid in the establishment of just democracy throughout the world.”

Peace Delegation in Session in Le Salon de L’Horlage, French Ministry of Defense in Supreme Conference in World History, President Wilson Is Seated to the Left of Speaker. U.S. National Archives, 165 WW 400A13. GGA Image ID # 191dc6bb98

Celebrations Abound!

Yeoman (F.) Estelle Kemper heard the announcement about the Armistice while working in the Navy Department Building in Washington, DC. She hesitated to believe the news because so many false reports had been made previously.

When it became evident that the day had finally arrived, ringing bells and blowing whistles reflected the joy of the moment. The capital city, as she remembers, was “so wild that night” that she and a group of friends could not find an establishment to dine at until midnight.

Spontaneous celebrations of every kind occurred around the country. Strangers hugged each other in their excitement. Yeoman (F.) Lou MacPherson Guthrie recalled, “Armistice Day was wildly exciting.

All offices closed. We danced in the streets with any passerby. Everyone was happy. Everyone laughed and celebrated. On 12 November, it was hard to get back to our humdrum duties.

But then began a series of parades to greet military brass and returning units. And there were parades of any old kind. The Yeomanettes were always in the vanguard.”

The members of the National Council of Women organized a national “Victory Sing” at 4:00 pm Eastern Standard Time on Thanksgiving Day.

Major D. J. Donovan, who processed the men drafted in the nation’s capital, observed, “Anybody who has been sending boys away since the war began couldn’t help but rejoice.

I’ve looked into the faces of so many mothers and wives and sweethearts, seen them trying to be brave with their hearts breaking, that I had the time of my life when I was able to give the good news to the crowd at the hut this morning.”

As Guthrie noted, the end of the war did not mean the end of duties for yeomen (F.). Secretary of the Navy Daniels needed their support during the demobilization of naval forces.

“Well Dones, Bravo Zulos”

There was no shortage of compliments for the Navy’s women reservists. Secretary Daniels commented, “These women yeomen, enlisting as reservists, serve as translators, stenographers, clerks, typists, on recruiting duty, and with hospital units in France. Too much could not be said of their efficiency, loyalty, and patriotism.”

Rear Admiral Samuel McGowan, paymaster general of the Navy, also praised them, noting that “the efficiency of the Navy’s entire supply system would have been impaired had it not been for the women reservists.”

Carlton Fitchett, a reporter and columnist in Seattle Washington, published a satirical commentary that read in part, “The dawn of peace has brought regrets as well as jubilation, for now we’ll lose the Yeomanette, who nobly served the nation. The ‘gobs’ will bid them fond good-bye, in spite of orders stringent, the day when they demobilize the power-puff contingent.”

The Norfolk Naval Recruit paid tribute to them: “The yeomanettes throughout the country by their association with the Navy have exerted an inspiring influence on the men of the service. No man can fail to do his part when the womanhood of the nation is answering the call so fearlessly.”

They not only gave outstanding service, they exceeded others’ expectations. “It is estimated that about 40 percent of the work at headquarters could be performed by women but authorities believed that three women would be needed to do the work of two men. However, the highly competent performance of women enlistees proved they were equal if not superior to men.”

Perhaps the highest recognition of their abilities was reflected in the Navy’s invitation to continue their jobs as civilians. Joy Bright Hancock, one of the most well-known yeomen (F.), worked for the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) between the world wars and helped launch the bureau’s newsletter.

She was a female reserve officer during World War II and became the third director of the Women Reserves after the war. Captain Hancock was one of the principal naval leaders assuring the passage of the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act of 1948, which gave women a role in the peacetime military.

Sarah Davis Taylor was one of the 14 African American yeomen (F.) transferred to civilian status as a clerk at the Navy Department, a position from which she retired 23 years later.

Charlotte Winters retired from her job at the Naval Gun Factory in the Washington Navy Yard with 34 years of service on 31 March 1953. Maguerite “Missy” LeHand’s work on Franklin Roosevelt’s 1920 vice presidential campaign led Eleanor Roosevelt to hire her to organize her husband’s correspondence.

Her duties over time culminated in her becoming Roosevelt’s personal secretary during governorship and later his private secretary during his presidency, starting in 1932.

She was known for outstanding work, her attention to detail, her ability to anticipate the president’s needs, and her loyalty to and admiration of the president.

She eventually became one of the president’s confidantes and a close friend of the family, periodically living with them. At the time of her death in 1944, President Roosevelt commented,

Memories of more than a score of years of devoted service enhance the sense of personal loss which Miss Le Hand’s passing brings. Faithful and painstaking, with charm if manner inspired by tact and kindness of heart, she was utterly selfless in her devotion to duty.

During Congressional hearings on the Navy retaining yeomen (F.) as civilians, Senator Carroll S. Page (R-VT), chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee “expressed warm sympathy with the desire of the young women to remain in Uncle Sam’s service, not as civilian employees, as the House is trying to make them do but as real Yeoman (F.) with all the characteristics of loyalty, spirit, and hard-working patriotism.”

Helen F. Harney, a Boston native, is an exception. She served from 1918 to 1928 and re-enlisted in August 1950. Her assignments included master-at-arms for the third-floor women’s reserve barracks at Naval Station Newport, Rhode Island. The Navy granted her a waiver to remain on active duty beyond the age of 65 to allow her to retire with 20 years of service.

Demobilization

“They had saved the day in war, and the Navy regretted the legislation which compelled the disbanding.”107 Josephus Daniels, former Secretary of the Navy, 1922

The Navy stopped recruiting women on 11 November 1918, but did not demobilize all of the female yeomen from active duty until 1919, because they had signed up for a four-year enlistment.

The Naval Appropriations Act of 11 July 1919 placed all reservists, including the females, on inactive duty. They received $12.00 per year until they officially discharged.

The majority of the yeomen (F.) officially separated from the Navy by 1920. Each reservist received orders documenting her change in status and a $60 gratuity per the Revenue Act of 1919.

The Navy issued war service certificates documenting the individual’s full name, serial number, term of service, and type of discharge. Chief Eunice Dessez and six of her colleagues at the Naval Reserve Enrollment Office at 10th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, S.E., in the District of Columbia completed certificates for all naval reservists in the area.

The Navy transferred the reservists’ service and medical records to the Bureau of Navigation. The yeomen (F.) also received the two-sided discharge certificates recording the details of their service, including their type of discharge, their rating, and their enrollment period. Secretary Daniels observed the last drill of yeomen (F.) in 1919.

The service-connected benefits for all veterans included membership in the American Legion and military preference when applying for civil service jobs. Also, the Bureau of Navigation awarded all Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard veterans a Victory Medal.

Mrs. Henry F. Butler recalled, “The only distinction I won as a grounded Navy enlistee came after the Armistice in 1918. Every member of the services was issued a medal on a rainbow ribbon.

This ‘Victory Medal’ was ‘general issue’ but the then Secretary of the Navy personally presented mine to me, with the conventional kiss on each cheek. A little French to be sure, but a very satisfactory honor!”

Reflecting on Their Service

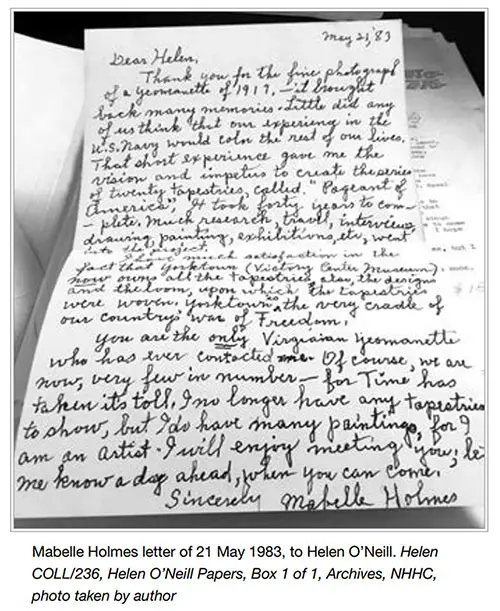

Mabelle Holmes Letter of 21 May 1983, to Helen O’Neill. Helen COLL/236, Helen O’Neill Papers, Box 1 of 1, Archives, NHHC, Photo Taken by Author. GGA Image ID # 191dc7eabb

The Navy’s first enlisted women cherished their opportunity to serve their nation during World War I and found their experiences to have a lasting impact on their lives. The following remarks are representative of what their service meant to them:

- “Thank you for the fine photograph of a yeomanette of 1917—it brought back many memories. Little did any of us think our experience in the U.S. Navy would color the rest of our lives. That short experience gave me the vision and impetus to create the series of twenty tapestries, called ‘Pageant of America.’ It took forty years to complete. Much research, travel, interviews, drawing, painting, exhibitions, etcetera went into the project.”

- “I will always be grateful for having served in the Navy, and for the privileges of being a Legionnaire and member of our unique organization.”

- “Having jobs and doing our ‘duty’ (as we saw it) fully compensated the Yeomen (F) in my acquaintance for their lack of money, lack of prestige, long working hours—even those uniforms—and we were sorry when the Navy gave us our ‘honorable discharges in 1919.”

- Susan Godson’s Proceedings article captured these thoughts: “We had a small part in the great Allied victory,” “I loved it and felt it was doing my bit,” former Chief Yeoman, “We didn’t realize it at the time, but we were trailblazers for women in the military,” and “I wouldn’t give up one single minute of my service.”

- Another yeoman recalled the pride of having “marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, in the capital of the nation, under the baton of John Philip Sousa, with our victorious troops returning home.”

Several yeomen (F.) met their spouses in the service and started families after the war. Their naval service introduced them to things they probably would not have encountered, enhanced their confidence, and, in some cases, increased their income. Like the men they replaced, they were very proud of their time in the Navy and enjoyed friendships that spanned their lifetimes.

Yeomen (F.) and the Fight for Equality

Honorable Discharges

Despite their notable wartime service, yeomen (F.) had to fight for the rights and benefits they deserved. In the shadow of a war to save the world for democracy, these women were not treated as equals.

Some officers, for example, gave other than honorable discharges to their female yeoman rather than honorable ones because they believed women would not enlist in the Navy again.

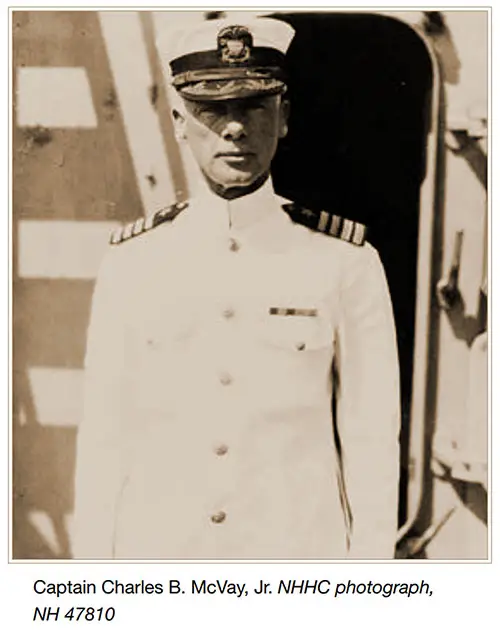

Other than honorable discharges led employers to think the veteran had done something wrong or inappropriate. The yeomen (F.)’s protests fell on deaf ears until they found an advocate in Rear Admiral Charles B. McVay, Jr., chief of the Bureau of Ordnance.

As soon as he learned of the situation, he informed Secretary of the Navy Daniels, which resulted in the Bureau of Navigation issuing guidance to naval districts and yards ordering them to grant honorable discharges to all who warranted them.

This decision did not escape the attention of the media. Earl Goodwin noted in his Washington Times commentary,

These women should not be discharged under a cloud of cheap sneers and criticism. They should be thanked, warmly, generously, and with the appreciation of the entire nation.

They should receive HONORABLE DISCHARGES. I want to tell you they have the esteem and love and appreciation of the entire United States. I trust a little thoughtless talk in a Congressional Committee room will not sink too deeply into their hearts. They deserve everything EXCEPT this sort of treatment.

Captain Charles B. McVay, Jr. NHHC photograph, NH 47810. GGA Image ID # 191ddec0a0

Adjusted Compensation Bonus

The Adjusted Compensation Bill enacted by Congress in 1924 excluded the yeomen (F.) while compensating the men with whom they had worked or who they had supervised. Paul McGahan, department commander of the District of Columbia American Legion, and Kenneth McRae, a member of the Senate press gallery, believed the act to be a gross injustice to the women who had served their country.

McGahan, along with McRae, appealed directly to members of Congress and successfully urged them to amend the bill to include women.

Helen O’Neill reported on this at a 1924 Jacob Jones Post No. 2 American Legion meeting: “A Bill Known as the HR 3242 (Adjusted Compensation Act) has been introduced by Republican Representative McKenzie (Chicago) on December 13, 1923.

This bill would exclude all Yeoman (F) from its benefits . . . The post passed a resolution petitioning the American Legion to protect and represent the interests of former servicewomen against discrimination as contained in the McKenzie amendment.”119

Naval Reserve Act of 1925 (43 Statute 1080)

In 1925, as a further affront to women, Congress recommended amending the Naval Reserve Act of 1916, which allowed women to enlist, to permit only males to serve.

They based their decision on their belief that there would not be another war and, should one happen, that women would not be recruited.

Former yeomen (F.) testifying before the Senate Naval Affairs committee argued that the proposed amendment was “an unmerited slur upon the services rendered by the women in the Navy.”

Republican Senator Tasker L. Oddie (R-NV) moved that the word “male” be deleted from the act.

Senator James Wadsworth, Jr. (R-NY), however, insisted that the deletion “involved far reaching, even unknown implications.” Lacking support for his motion and not desiring to delay the bill, Senator Oddie withdrew his motion.

Thus, the Naval Reserve Act of 1925 (43 statute 1080) eliminated the possibility of women serving in the reserves.

Regina T. Akers, Ph.D., "Chapter 4: Changing the World, Their Lives, and the Navy," in The Navy’s First Enlisted Women, Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, 2019.