Eat, Drink and Be Merry at Camp Dix - 1917

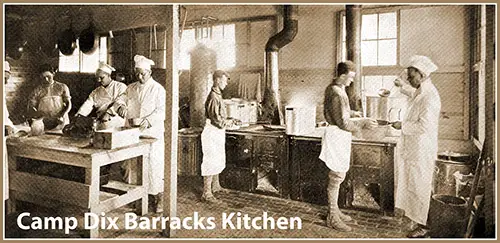

Camp Dix Barracks Kitchen. The Camp Dix News, 29 September 1917, p. 2. GGA Image ID # 1ce46783a1

When the new army cooks at Camp Dix finish with a soup bone, there will not be enough of it left to make good bone buttons. The best cooking and no waste will be the watchword. This is the task the heads of the School for Bakers and Cooks have undertaken to accomplish.

Captain C. J. Kalberer, Q. M. U. S. R., remains in charge, with Sergeant, Sr. Gr. Q. M. C., Supervisor of Cooking and Baking. Sergeant James S. Boyatt, Sr. Gr. Q. M. C., Chief Instructor in Baking, takes the place of Sergeant Horace Hahn, who was recently transferred, while Lieutenant George H. Sunderman is Commanding Officer of the Bakery supplying the Camp with bread.

The Government intends to feed the new army in the Cantonment here at a cost of $0.397 per day per man. It can, therefore, be readily seen that not only must all scraps be used and nothing wasted, or spoiled in cooking and preparation, but somewhere between the Quartermasters' stores and the men's mess table there must also be a careful accounting of the quantity and cost of everything used.

If any restaurateur or economist thinks it a simple problem to provide a man with three meals a day of well- balanced and nutritious food, sufficient to put fighting "pep" into him, and all for the low cost of 40 cents—well, just try it.

Yes, this is a challenge to any civilian hotel steward and chef, any restauranteur or even the most economical housewife. And it must be remembered that the purchasing agents of the Quartermasters ' Department have to contend with the same high prices that the civilian has.

Buying, however, in immense quantities and in bulk the army gets the benefit of much better prices than the housewife who buys the same food but in small, dainty and expensive cartons, tins and glass containers at the corner grocery. However, many of the big hotels and restaurants have refrigeration and means of preserving food almost equal to those at Camp Dix.

Where the large hostelry or eating house loses out on cheap meals as compared with the army is in adhering to the custom of pandering to the capricious palates of each individual, thus necessitating the endless variety provided on the bill of fare in our hotels and restaurants, as well as in many homes.

In feeding, say, 200 men on the same menu there is , of course, an immense saving over the carte de jour. We venture to say that many of the lessons now being taught at the Army School for Cooks and Bakers could be well applied in the home, the hotel and the restaurant in cutting down the high cost of plain living.

At present, besides the heads above named, the School for Bakers and Cooks includes 15 officers who act as assistant instructors in charge of regimental schools throughout the Camp.

At the school there are under training at present 84 cooks, 25 bakers and under the 15 assistant instructors 60 sergeants first class, one of the assistant instructors being assigned to each regimental school.

A number of the men being in structed at the school are Regular Army cooks, who are receiving further pointers on how to provide menus so as to remain within the specified lim its of ration cost. About forty of these men were formerly at Panama.

About 75 are student cooks from the new National Army. Several hours each day are devoted to lectures and to practical demonstrations.

For instance, the Supervisor of Baking and Cooking will have a quarter of beef brought out on a table and with several dozen men around him, each provided with a manual, he begins to explain all the points about that quarter of beef a good cook should know.

First, he calls attention to the points which distinguish whether the quarter came from a cow, a steer or whether it is “bully beef," as shown by the shape of the quarter, shape of the bones, amount of fat and lean at certain points, color of the meat.

The fact that the color of the fat tells whether the animal corn fed or pastured is also touched on. Then the Supervisor digs his knife in between the vertebrae of the backbone to see whether solid or not, cuts off a thin sliver of cartilage from another bone and by the hardness, color and presence or absence of blood spots, and his knowledge of the sex of the animal, advises the men that it was about three and a half years old.

The lessons regarding canned meat are just as thorough, and with instruction like this there is very little chance of a repetition of the embalmed beef scandal of the Spanish-American war. The men in the kitchens will be able to tell us exactly what they’re getting.

But it is not enough for the cooks to know what they are getting. But, knowing what they have, the Supervisor now proceeds to show them how to cut up the quarter in the easiest manner and to the best advantage, designating the different cuts by reference to the manual in the hands of the men.

As he takes off the different cuts, he explains the nutritive value and the best method of roasting, boiling, stewing, or frying each part, so as to get all possible nutriment out of the meat. Then he gets down to the hard facts of the bone, how to extract and use the marrow, how to crack and boil the bone and how long to let it simmer so as to obtain all the gelatin and juice possible.

Exit beef, exit entire class squad with instructor and mess kit with ration of rice, bacon, coffee, and sugar. Sergeant Borth selects a likely spot not under enemy observation, digs a hole, builds a tiny fire in said hole safely hidden even from air scouts, and , in this instance, well camouflaged by an interested group of rookies.

Presto, nice soft, flaky white rice with a piece of fried bacon, to supply fat and salt, and steaming hot coffee.

This latter instruction is intended to prepare the men to be able to have a hot meal in the trenches and outposts under the very noses of the enemy, and when thrown entirely on their own resources and packed rations. With some practical advice on how to clean the aluminum utensils of the mess kit, the lesson is ended.

After being shown how, the men take two trys at it themselves, and each man is given a percentage on the results of his second effort with the mess kit.

This, of course, has been following just one line of instruction. Lectures and demonstrations are just as thorough on the different ways of cooking and baking beans, the concoction of pies and the mysteries of hash.

We now mix up the dough with the Commanding Officer of the Bakery and the chief instructor in baking and learn that about 18,000 pounds of bread were baked daily this week to supply all the boys in Camp. Now that about 10,000 more men are arriving from New York State, Lieutenant Sunderman and his Company of bakers will soon be baking about 15 tons daily.

And here is what goes into the Kriegsbrot: 100 pounds of flour, mix with 7 gallons of water, adding about two pounds each of salt, sugar and lard and one pound of yeast. Knead, set and bake. But, and here's the rub, it's learned only by actual experience , hence an Army School for Bakers. The 25 bakers will be under instruction for two months, and then a new squad will be put under tutelage. The same period of two months' instruction applies to the cooks.

In addition to all the practical work and instruction given the cooks and bakers so they may be able to feed the boys at the front properly, there is also a class in arithmetic at this School of Cooking and Baking.

All students graduating as first cooks or mess sergeants must be competent to figure the cost of rations and remaining within the prescribed garrison cost limits ; that is, $39.70 per hundred men per day. The system of accounts is complete but simple.

To illustrate, 212 men were fed at the School several days ago, using a "common” mess menu, three meals at a total cost of $48.00 , or just about 23 cents per man. This menu as follows:

Breakfast:

- Boiled rice and milk,

- Hot muffins,

- Fried bacon,

- Fried potatoes,

- Bread and butter,

- Coffee or milk.

Dinner:

- Puree of bean soup,

- Croutons,

- Soft roast beef,

- Stewed kidney beans,

- Sweet potatoes,

- Tapioca pudding,

- Bread and butter,

- Coffee or milk.

Supper:

- Meat potato pie,

- Hot biscuits,

- Fresh apple sauce,

- Bread and butter,

- Coffee or milk.

As may be seen this menu cost about three - fifths of the ration allowance. This, therefore, allows a little occasional splurging in the direction of banquets. The Sunday bill of fare, for instance, is usually more elaborate than the “common” menu. The following is the appetizing menu on a Sunday at the Cookery School:

Breakfast:

- Scrambled eggs,

- French toast,

- Bacon,

- Cottage fried potatoes,

- Bread and butter,

- Milk or coffee.

Dinner:

- Vegetable soup,

- Soft roast of beef,

- Mashed potatoes,

- Bread and butter,

- Creamed peas,

- Stewed peaches,

- Chocolate cake,

- Coffee or milk.

- Beef steak pot pie,

- Sliced tomatoes,

- Browned potatoes,

- Rice pudding,

- Bread and butter,

- Coffee and milk.

Supper:

For the mess sergeant the bill of fare, however, does not start with breakfast, but with supper. With the assistance of his cook on shift the mess sergeant prepares his bill of fare, so as to utilize all leftovers from breakfast and dinner so that food is not kept too long before being used again.

There will be a profusion of all kinds of biscuits, as one of the objects sought for is to be able to put flour into as many different forms as possible. There will also be pies for Sundays and other times to vary the dessert, but the latter will be looked upon more or less as a luxury.

The mess sergeants have a multitude of duties, probably the most important being to caution the men about wasting the food by taking more on their plates than they can eat. What is taken on the plates is not used again; what remains on the platters and serving trays, etc., is returned to the kitchen to be served again in some other form. The secret of running a mess is no waste.

"Eat, Drink and Be Merry," in The Camp Dix News, Wrightstown, NJ, Philadelphia: Irwin & Leighton, Vol I, No. 7, Saturday, 29 September 1917. pp. 2, 12.