America's New Soldier Cities - 1917

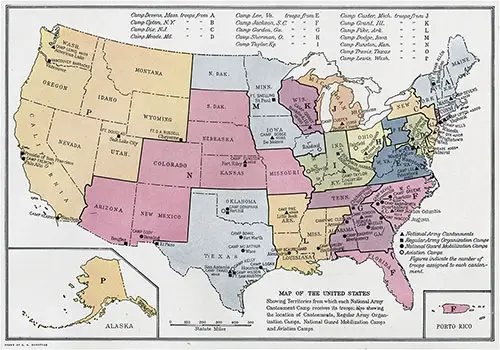

Map of the United States Showing Territories from which Each National Army Cantonment Camp Receives its Troops; Also Showing the Location of Cantonments, Regular Army Organization Camps, National Guard Mobilization Camps, and Aviation Camps. National Geographic Magazine, November-December 1917. GGA Image ID # 17de77cf33

After the Congress had decided on raising a vast army of citizen-soldiers and had formulated plans for calling that army to the colors, the Quartermaster General was confronted with the problem of housing the army adequately during the long process of converting it from an unorganized multitude of individuals into a highly developed fighting machine.

Colonel I. W. Littell, since promoted to a brigadier generalship, an assistant of General Sharpe, the Quartermaster General, was in charge of that branch of the Quartermaster General's Office known as the Construction and Repair Division, and it therefore fell to the lot of Colonel Littell to take charge of this great task.

For years Colonel Littell had gone about his work just as a hundred other colonels had done, and his appointment to the heavy task of housing all the new military forces was his first introduction to the world at large, even as the appointment of Colonel Goethals as builder of the Panama Canal brought a new national figure upon the stage.

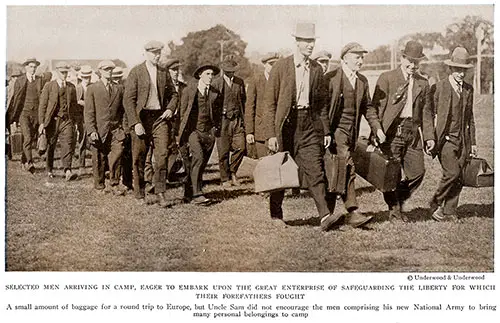

Selected Men Arriving in Camp, Eager to Embark Upon the Great Enterprise of Safeguarding the Liberty for Which Their Forefathers Fought. A Small Amount of Baggage for a Round Trip to Europe, but Uncle Sam Did Not Encourage the Men Comprising Many Personal Belongings to Camp His New National Army to Bring. Photograph © Underwood & Underwood. National Geographic Magazine, November-December 1917. GGA Image ID # 18cc369f7f

There is no record of what Uncle Sam said to the builder of his soldier cities, but the facts in the case would have warranted his giving these instructions:

“I have placed in the Treasury of the United States, subject to your order, a sum of money which is equal to all the gold produced by all the mines of the world during the past year.

With this money I want you to house my armies while I get them into shape. In the first place, I want you to build 16 great military cities in as many sections of the country.

These 16 cities must be capable of housing a population equal to the combined population of Arizona and New Mexico. There must also be stable room to care for as many horses as there are in the State of Oregon.

“Furthermore, you must establish hospitals to take care of as many sick and wounded people as are to be found in all the hospitals west of the Mississippi River in normal times.

“Nor is that all. You are to provide all of the mess halls and other general buildings for all of the 16 National Guard mobilization camps. And while you are doing that you will not forget your regular work of expanding and keeping in repair the housing facilities of the Regular Army posts.

“Nor will you overlook the fact that as soon as all that work is under way you will be expected to undertake the construction of the two big concentration camps from which the American army will embark for France and through which its supplies will reach the front.

“Yes, I know it is a large order—in fact, a tremendous proposition—but these are tremendous times, and I’ll have to ask you to execute it within four months. Of course, I realize that you will, in its execution, spend the money three times as fast as the world mines its gold, but at the same time I expect you to render an account which will show that every penny has borne an honest burden.”

A Notable Achievement in The History of Building

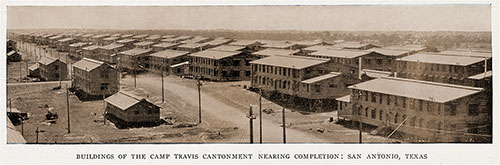

Building of the Camp Travis Cantonment Nearing Completion: San Antonio, Texas. National Geographic Magazine, November-December 1917. GGA Image ID # 18ccdcc160

Such was the order. It has been executed as the American Army always has executed its orders—to the letter!

The story of the 16 National Army cantonments surpasses anything else in the history of building. Such, indeed, has been the transformation wrought at these cantonments that the world might well have believed it all magic had it not heard the rhythmic blows of 25,000 hammers driving home 1,200 miles of nails a day; had it not seen enough lumber go from the country's mills to these camps to make a boardwalk four feet wide— runners and all—from Palm Beach to Bagdad via Bering Strait and the Arctic Circle; had it not witnessed the movement to their sites of enough material and supplies to load a string of cars reaching from Portland, Maine, to Portland, Oregon, via Boston, Cleveland, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Spokane.

Consider a weekly payroll twice as large as the monthly payroll in Panama when the canal work was at high tide, and paid off in two hours, where three days were required to pay off the big ditch force. Reflect upon the fact that the expenditure for the 16 cantonments for the month of August was $52,000,000—nearly nine tons of gold, or more than was ever paid out in a whole year on the Panama Canal, until now the world’s greatest undertaking!

Important Details Considered in The Selection of Camp Sites

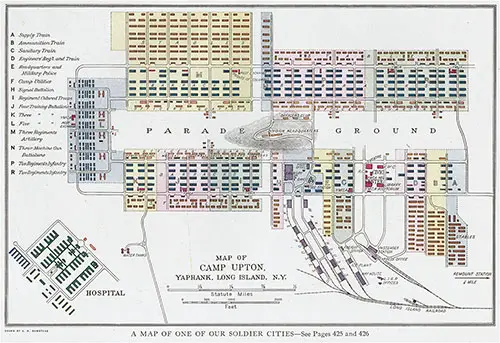

A Map of One of Our Soldier Cities - Camp Upton, Yaphank, Long Island, New York. National Geographic Magazine, November-December 1917. | GGA Image ID # 18cd10bcf0

There were many things to consider in the choice of locations. Each camp had to be contiguous to a city, in order to insure a labor and material market within reach, opportunities for camp leave to mitigate the tedium of the military grind, and satisfactory railroad facilities. The topography of the surrounding country, the available sources of an ample water supply, and the problem of drainage were also important considerations.

Some of the sites departed just enough from level to insure good drainage, and for the most part were fine and prosperous farms, as at Camp Grant, Rockford, Ill.; Camp Sherman, Chillicothe, Ohio, and Camp Dix, Wrightstown, N. J. Others were covered with undergrowth and scrub forest, as at Camp Devens, Ayer, Mass., Camp Upton, Yaphank, N. Y., and Camp Pike, Little Rock, Ark.

Others were on military reservations, as at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kans., and Camp Travis, Fort Sam Houston, Tex. At Camp Lee, Petersburg, Va., 25 farms were occupied. At Camp Jackson, Columbia, S. C., a negro church had to be razed and several old tobacco barns burned.

With the sites selected and 160 of the biggest sawmills in the United States turning logs into planks, joists, rafters, and studding at an incredible speed, the cities themselves were ready to begin rising from the ground.

The railroads of the country, already sore pressed for rolling stock, already taxed to what seemed well-nigh the limit of wartime demands on peace-time facilities, set aside 30,000 cars for cantonment material transportation, and vast quantities of lumber were moving east, west, north, and south to the camp sites. In a single day there was unloaded at Des Moines 1,890,000 board feet of lumber, the equivalent of 300 miles of 12- inch boards.

One day a one-story office building, some trenching machines, some teams and trucks, and a chaos of materials, and in 48 hours a respectable village. In two weeks the village had grown to a town, and in two months the town became a city.

How the work marched along may be told in the story of Camp Funston.

On June 20 a contract for the building of the cantonment was let. For the next 15 days there was little done, because the site was not definitely chosen. There were four available sites on the Fort Riley Reservation, and a civilian board was named to select one of them. The decision was not made until July 5.

Meanwhile the local construction quartermaster, having an inspiration that the site, which was finally chosen would be the one, as well as a feeling that taking a chance was better than living out a delay, told the contractor to erect buildings for the quartermaster, the field auditor, and the contractor.

These were ready when the site was fixed, and were the only buildings standing on July 5. when the real work began. By July 10 the Union Pacific Railroad had a siding completed two miles long, and later installed more than eight miles additional.

Workmen Quartered in Camps They Were Building

The buildings followed the standard plans from Washington, which specified that all northern cantonment structures have outside walls and ceilings lined with paper, and that they be wainscoted and lined inside with wall board; all lavatory buildings should have concrete floors and foundations.

The men at Camp Funston did not stop for Sunday but worked io hours a day seven days a week, with Saturday afternoon off. They worked 65 hours a week and were paid for 80 hours, at Kansas City union labor prices.

Four thousand eight hundred men were housed and fed at Camp Funston when the work was in full blast. The government allowed them to be quartered in buildings which were already finished, except for the wall board work and top flooring inside. Three hundred commissary employees, cooks, waiters, and room attendants were required to care for that half of the force which lived at the cantonment, the other half living in neighboring towns and surrounding country.

The army of builders ate two carloads of beef a week and other things in proportion. Meals were furnished at 30 cents each, the men being required to purchase a week’s tickets at a time. This was exactly the rate charged the Americans at the line hotels on the Panama Canal. Quarters were provided free, except that each workman upon first entering the bunkhouse deposited a dollar, which was returned to him when he finally left the job.

Special efforts were made to keep the workmen contented and happy. One of the barracks was turned over to the YMCA, which established outdoor motion- picture shows, where three times a week the best films were shown, free to all comers. A band and an orchestra were organized, and baseball teams were equipped.

Camp Newspaper Stimulated Men to Special Effort

The spirit displayed in the construction of all the cantonments was an inspiration to everyone who witnessed the work. A healthy rivalry among the 16 contractors was in evidence everywhere.

The contractors at Camp Dix published a construction weekly, which served to fire the zeal of the men there, even more than the Canal Record stirred the big army of diggers at Panama. In the Camp Dix News the editor put everything of interest to the force, from a description of the cantonment and the week-to-week story of the work’s progress, down to a picture of a bare-skinned Chihuahua dog, the camp mascot, and a piece of advice to an unnamed youngster working in camp not to neglect writing to his mother.

Through this newspaper the contractors appealed to their men to help put Camp Dix “first under the wire” of completion. “There are 16 entries,” said the appeal, “in the most spectacular race that American contractors have ever been called upon to enter. We have a good start and a fair field, and we need only supply the stamina.” So, even in building good sportsmanship had its place.

Men Behind the Hammers Imbued with Patriotic Spirit

The men behind the hammers soon caught the spirit of the times. At Camp Dix the contractors divided their organization into io groups, each with a section of the camp to build. Soon the 16 cantonment national sweepstakes event had a side attraction—the io-section Wrights- town race. Each group at Camp Dix was as keen “to put one over" on its rivals as each contractor was to bring his cantonment under the wire first.

One day one of the competitive groups of camp builders bethought itself of the fact that there ought to be a flag flying over its section. The hat was passed, and from water boy to section superintendent all “chipped in” to buy & starry banner and a flagpole.

With telegrams from the President and the Secretary of War to be read, with speakers of note to set the event in an appropriate wreath of words, and with a band to bring the thrill which the national anthem inspires, Old Glory was hoisted into place. Soon every other section had its flag, each raised with appropriate ceremony, and all unfurled to the breezes through the initiative of the hardworking carpenters themselves.

There was cooperation everywhere. Even the thousands of negro laborers at the Southern cantonments became imbued with enthusiasm for their work and heartily supported every effort to keep the camp sites up to the 100 percent mark in sanitation, although sanitary science is well-nigh a sealed book to them.

Can you imagine several thousand Virginia negroes, in the midst of the watermelon season, with the Hanover crop in all its luscious luxuriance hard by, and not a rind to be found on a camp site thousands of acres in extent? It may have tried their souls to abstain, and vet the site of Camp Lee was as free from watermelon rinds as it was free from polar bears or African lions.

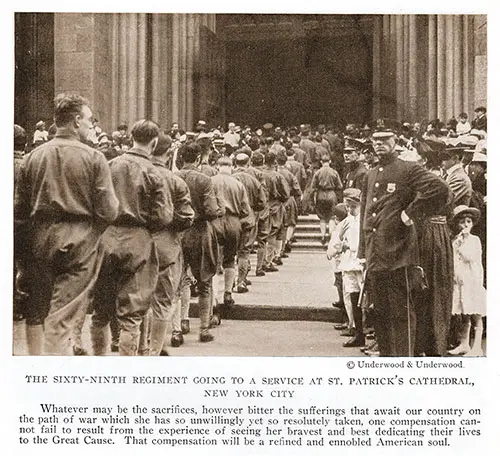

The Sixty-Ninth Regiment Going to a Service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. Whatever may be the sacrifices, however bitter the sufferings that await our country on the path of war which she has so unwillingly yet so resolutely taken, one compensation cannot fail to result from the experience of seeing her bravest and best dedicating their lives to the Great Cause. That compensation will be a refined and ennobled American soul. Photograph © Underwood & Underwood. National Geographic Magazine, November-December 1917. GGA Image ID # 17dd975d5b

One Camp Bakery’s Capacity 80,000 Pounds of Bread A Day

With such a spirit as this pervading every cantonment, little is the wonder that in less than four months enough buildings were erected to make, if placed end to end, a continuous structure reaching from Washington to Detroit.

To appreciate the dimensions of the cantonments they must be considered in their units. Camp Devens, for instance, with one exception the smallest of the 16,

has a refrigerator plant capable of making 20 tons of ice a day, besides keeping many tons of food chilled to the freezing point. Its beef cooler will hold 120 cattle. The bakery has a capacity of 40,000 2-pound loaves of bread every 24 hours. The auditorium of the YMCA has a seating capacity of 2,800 men—nearly one and a half times as many as any theater in the nation’s capital.

In small things as well as large the story of the military cities runs into amazing proportions. The 16 cantonments required 350 carloads of cooking ranges for their equipment, 2,500 carloads of heating stoves, and 112.000 kegs of nails. Sold at ordinary retail price, the total product of their bakeries would amount to something like $125,000 a day.

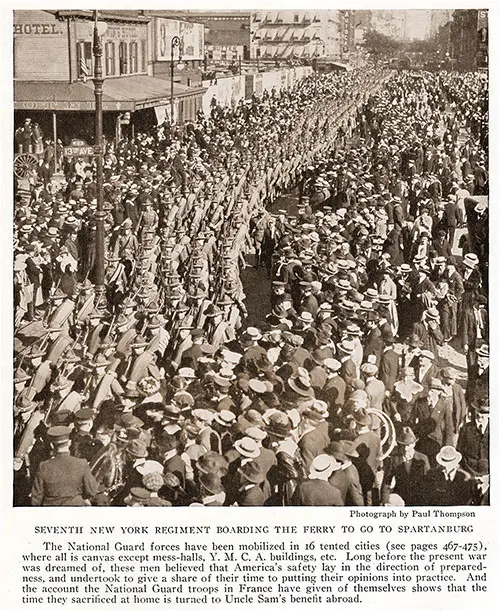

Soldiers from the Seventh New York Regiment Boarding the Ferry to Go to Spartanburg. The National Guard forces have been mobilized in 16 tented cities, where all is canvas except mess-halls, YMCA buildings, etc. Long before the present war was dreamed of, these men believed that America’s safety lay in the direction of preparedness and undertook to give a share of their time to putting their opinions into practice. And the account the National Guard troops in France have given of themselves shows that the time they sacrificed at home is turned to Uncle Sam’s benefit abroad. Photograph by Paul Thompson. National Geographic Magazine, November-December 1917. GGA Image ID # 17de9fbebe

Making Waste Pay

A problem which early arose in planning the cantonments was that of disposing of the wastes. Had it been decided to burn the garbage and other refuse of the camps, the installation of huge incinerators would have been necessary; but happily the idea of the salvage of wastes, something of which armies never thought before this war, was conceived by a National Guard officer from Delaware.

This officer wrote the War Department saying that from his experience in handling troops he believed a great saving could be accomplished by collecting and selling all garbage and refuse.

The suggestion appealed to the Quartermaster General, and the Delaware officer was called to Washington and assigned the work of developing a plan to conserve the waste materials at the several cantonments.

Under his plan all such materials are sorted and placed in separate cans—one for garbage, one for bones, another for fats, another for grease, and others for paper, tin cans, bottles, etc.

The garbage from 13 of the cantonments is fed to hogs. Experience has shown that the garbage incident to the feeding of from 10 to 15 men will feed one hog. On this ration it has been found that the hogs take on a pound of flesh a day for the first 150 days.

The garbage from a cantonment is, therefore, sufficient to feed approximately 4,000 hogs, which would show a gain of more than 9,000 tons of meat per year for the 13 cantonments, if the stock is kept up to the maximum number. In the three remaining cantonments the garbage is reduced to grease, which is used in the manufacture of soap, candles, and Glycerine.

The bones gathered will first have the grease extracted and then will be ground into bonemeal for fertilizer. The bottles at each cantonment will be sorted, sterilized and used again for commercial purposes. It is estimated that each cantonment will yield about five tons of wastepaper a day.

The waste materials from the National Army cantonments and embarkation camps have been sold to contractors for $446,000. In addition to this, the stable manure has been sold for $198,000, making a total of $644,000.

Thus not only has there been a salvage of nearly $700,000 from wastes, but an additional saving of $700,000, which, under the old system, would have been expended in the installation of incinerators. To this must be added the saving of $362,000 in the annual cost of operating these incinerators.

How Dirt Has Been Outlawed

If an army marches on its stomach, it keeps itself in health by its water supply. Nowhere else is cleanliness such a virtue as in the life of the soldier.

Until that lesson was driven home by the ever- higher ratio of deaths from disease than from gunfire, the value of water, good water and plentiful good water, was not appreciated.

But when wars were over, and statistics analyzed it was found that more men were killed and injured in their battle with uncleanliness than with the foe in front of them.

So dirt was outlawed. Uncle Sam provides in his big cantonments, his training and concentration camps, a water supply capable of meeting any demand that the ends of cleanliness may make. The story of the construction of the water systems of the several cantonments may be told in general terms by describing the system at Camp Dix.

The supply at that camp comes mainly from New Lisbon, more than three miles distant. It is taken from the north branch of Rancocas Creek, the headwaters of which drain wooded, uncultivated land, on which cedar, scrub oak and pine grow.

The soil is black and white sand, and through it the water percolates into the drainage substrata. In many places the cedar predominates, and the water coming in contact with its needles and roots is given a slight amber tinge and acquires a faint but pleasant cedar taste.

Giant Trenching Machines Used to Lay Water Mains

The three pumps which lift the water out of the creek and drive it three miles across country and up into the huge storage tanks of the camp have each a daily capacity of 1,500,000 gallons of water.

Each pump is driven by a steam turbine which occupies scarcely more space than the chassis of an army motor truck, but which is powerful enough to do the work of a thousand men. Every minute of the day and night, it drives a thousand gallons of water up a figurative hill 245 feet high, to the top of the highest water tank in Camp Dix; and it has to fly around at the rate of 83 revolutions a second to do its work.

A 16-inch cast-iron water main, more than three miles long, carries the water to the camp. Giant trenching machines, walking forward at the rate of 120 feet an hour, dug a ditch up hill and down dale four feet deep and 20 inches wide.

After the trenching machine came the pipe-layers and caulkers, and behind them the trench-refilling machine, which brought up the rear of the procession, with a filled ditch dragging out behind it.

A giant steel tank 127 feet high, on the camp site, holds 200,0c» gallons of water and each of three reserve wooden tanks holds a similar volume.

From these tanks the water is conveyed to more than 10,000 faucets, sinks, showerheads, water-closets, and fire-hydrants by 28 miles of pipes. And these figures are exclusive of the remount station and the base hospital water systems.

It was originally planned that the main pipeline should be of California redwood stave pipe, so as to spare iron for more warlike purposes, but the wood did not arrive fast enough, and iron mains had to be requisitioned.

Redwood pipe was used at as many of the camps as traffic conditions would allow, for not only does water flow through wooden pipe with less friction, and therefore in greater quantity for a given diameter of pipe, but it keeps cooler in summer and is less liable to freeze in winter.

Redwood pipe has been known to be serviceable even after half a century of use. The staves are held together by heavy galvanized wire wrapped at a tension of 7.000 pounds. Before being laid, the pipe is coated with asphalt.

Despite the utmost precautions taken to insure the purity of the water supply and the elimination of the menace of contamination from sewage, and in spite of all that is done to hold contagion in check by vaccination and isolation, men in the army still need hospitals. There is no place for home nursing in company barracks or officers’ quarters.

Three Hospital Beds for Every Hundred Men

Each cantonment has at least 1,000 hospital beds, and some have 1,600. It is estimated that, with adequate provision for emergencies of training-camp life, three beds will suffice for each 100 men.

Eternal vigilance is the price of health in the army, and each hospital is equipped with the most modern of laboratories, where water specialists, food specialists, meningitis specialists, typhoid specialists—in fact, every kind of specialists— labor who can aid, with Argus-eyed microscopes, in the great work of detecting anything and everything that might threaten the health of the men.

Above all things, Uncle Sam is determined that the men he has called to the colors shall have but one enemy to fight, and that disease shall not be permitted to play the role of ally to the foe.

What an Aroused Democracy Can Do

The building of the military cities to house American armies while on the home soil was an unprecedented ta>k, executed in the face of unheard-of difficulties, with unrivaled speed and in an unparalleled spirit.

It is America’s answer to the world that has mistaken her natural love of peace for an unwillingness to go to war, even for its preservation. It shows what a democracy, aroused to necessities of the hour, can do.

It shows that the genius of organization, which is the secret of twentieth century success in war, dwells under American skies, and that the spirit of ’76 never dies, but only lies dormant in the years of peace.

William Joseph Showalter, "America's New Soldier Cities: The Geographical and Historical Environment of the National Army Cantonments and National Guard Camps," in The National Geographic Magazine, Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, Vol. XXXII, Nos. 5 and 6, November-December 1917, pp. 437-446.