SS Red Cross Archival Collection

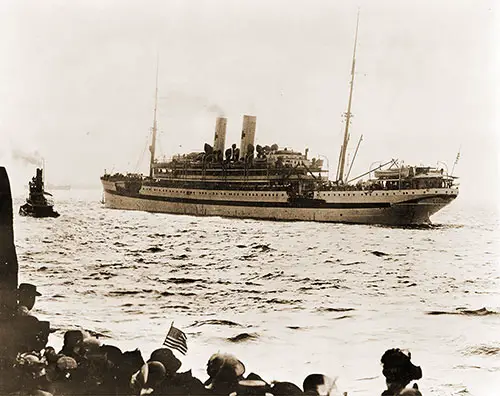

SS Red Cross of the Hamburg-American Line, Setting Sail on its Voyage of Mercy in September 1914. Photo by International News Service. | GGA Image ID # 20779e3806

Content Links

- Top Image: SS Red Cross of the Hamburg-American Line

- Red Cross (1899) Hamburg-American Line Ship's History (Brief)

- Passenger Lists

- Menus

- Autographs

- Photographs

- The European War and The American Red Cross - 1915

- Books Referencing the SS Red Cross

Red Cross (1899) Hamburg-American Line

Sailed as the SS Red Cross from 1914 to 1917.

Built by "Vulkan", Stettin, Germany. Tonnage: 10,532. Dimensions: 499' x 60'. Propulsion: Twin-screw, 16 knots. Quadruple expansion engines. Masts and Funnels: Two masts and two funnels. Previous Names: Hamburg (1899-1914). Renamed: (a) Powhatan (1917) (b) New Rochelle (1920) (c) Hudson (1921) (d) President Fillmore (1922). Fate: Scrapped in United States, 1928.

Return to Content Links

1914-09-13 SS Red Cross Passenger List

- Steamship Line: Hamburg Amerika Linie / Hamburg American Line (HAPAG)

- Class of Passengers: Surgeons and Nurses of the American Red Cross

- Date of Departure: 13 September 1914

- Route: New York to Falmouth, England

- Commander: Captain Armistead Rust, U.S.N. (Retired)

Return to Content Links

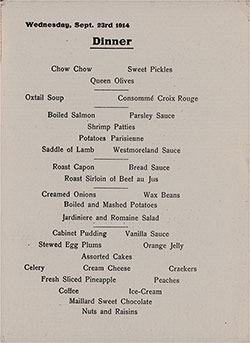

1914-09-23 SS Red Cross Dinner Menu

Vintage Dinner Menu from 23 September 1914 on board the SS Red Cross of the Hamburg-America Line featured Boiled Salmon, Roast Sirloin of Beef au Jus, and Ice Cream for dessert.

Return to Content Links

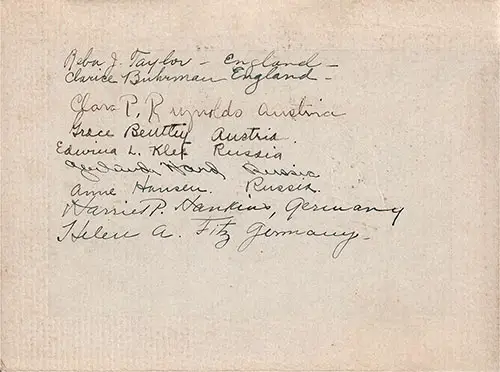

Autographs Included in the SS Red Cross Passenger List, 13 September 1914. | GGA Image ID # 17849c858b

Return to Content Links

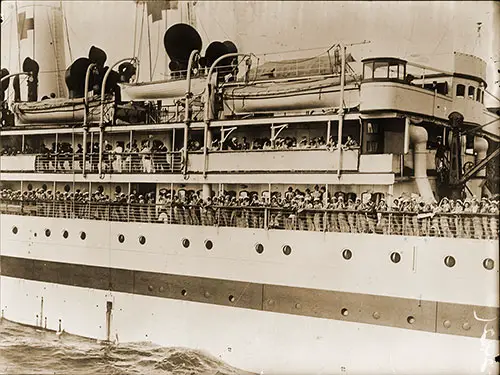

Red cross nurses going aboard the mercy ship SS Red Cross of the Hamburg-American Line, 13 September 1914. Photo by Underwood & Underwood, NY. Library of Congress LCCN 2017673096. | GGA Image ID # 207756801b

Group of Red Cross Nurses on the Deck of the SS Red Cross Prior to Departing for Europe, 13 September 1914. Photo by Bain News Service. Library of Congress LCCN 2014697383. | GGA Image ID # 2077e235c7

Red Cross Nurses Aboard the SS Red Cross En Route to France, 13 September 1914. Sectional view of the "Red Cross" with surgeons and nurses lined along the railings. Photo by Underwood & Underwood, NY. Library of Congress LCCN 2017672947. | GGA Image ID # 2077db6a7a

The SS Red Cross Departs from New York for Falmouth, England and on to Europe, 13 September 1914. Photo by American National Red Cross. | GGA Image ID # 207857aecc

Red Cross Nurses Relax On Their Deck Chairs on the SS Red Cross. Photo by American National Red Cross, September 1914. | GGA Image ID # 207860d2cc

-InChargeOfRedCrossDoctorsAndNurses-1914-BNS-LC-2014697106-500.jpg)

Major Robert Urie Patterson (1877-1950), a U.S. Army Officer Who Was in Charge of the American Red Cross Surgeons and Nurses Who Left on Sept. 13, 1914 and Went to Europe at the Beginning of World War I. Photo by Bain News Service. Library of Congress LCCN 2014697106. | GGA Image ID # 20780c93fc

-ANRC-LC-2017668654-500.jpg)

Miss Helen Scott Hay, In Charge Head Nurse on the SS Red Cross Voyage to Europe. Photo by Clinedinst of the American National Red Cross, June 1920. | GGA Image ID # 20785524ef

Return to Content Links

In the southeastern part of Europe lies the group of small countries that have long threatened the peace of the entire continent. The act of a Serbian fanatic in the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne brought matters to a crisis. It launched Europe into the greatest and most terrible war in history.

The Gathering of Storm Clouds

For many years the thunderclouds had been gathering, the mutterings of the Balkan wars had made thoughtful people apprehensive, and the flashes of suspicion and resentment that played like summer lightning across the skies gave warning of the tempest that was soon to come.

The causes of this mighty conflict are far deeper and more complex than our people generally understand.

The Red Cross, it has been said, is even more blind than justice, and amidst accusations and recriminations by word and pen, amidst the suffering, misery, and death of battlefields and devastated lands, it moves undisturbed on its merciful mission. It hears and heeds only the pitiful cry of humanity and cannot stop to question why.

The German Declaration August First

Austria had declared war on Serbia, and Russia began the mobilization of its armies. August first came the German declaration and France joined her eastern ally. Ere long, the onrushing storm burst over Belgium and England, too, and all Europe trembled in its fury.

Back to their posts of duty came such American Red Cross officers as, after a busy year, they were seeking a little rest. A joint meeting of its International and War Relief Boards was held, and a decision was reached to offer to every country the aid of our trained personnel and the contribution of hospital supplies.

Acting in strict accord with the Treaty of Geneva, this offer was made with the consent of the United States Government and communicated by the State Department to the governments of the belligerent nations.

By all, the offer was accepted, except for Belgium, which at that time desired only supplies and did not ask for the personnel until the spring of 1915. Japan later declined any assistance, as her great Red Cross organization was able to meet all demands upon it, and Italy, when it entered into the conflict, asked for only certain supplies.

At the request of the Secretary of War, the services of the National Director, Mr. Bicknell, were loaned to aid the Assistant Secretary in his mission abroad for the benefit of American refugees, and later, Mr. Bicknell's services were given to the Rockefeller Foundation for noncombatant relief in Europe.

Offers Of Aid by The American Red Cross on The Fifth

Plans were immediately inaugurated to secure funds and supplies and prepare the personnel. Day and night factories worked to provide absorbent cotton, bandages, and anesthetics. The sudden demand for such articles came from foreign governments and the Red Cross.

With plants adapted only to normal conditions, filling the orders that overwhelmed the manufacturers was not easy. The spirit of helpfulness that the Red Cross met on every side was its greatest asset.

The Relief Board issued an appeal calling attention to the contributions the European Red Cross societies sent during our war with Spain and asking for a generous response to enable our Red Cross to do its duty.

In this appeal, the people were told that "the donors may designate contributions for the aid of any special country and will be used for the country designated."

Yet, despite this assurance, many people persisted in asserting that those desiring to aid a special country could not entrust funds and supplies to the Red Cross, which would use contributions only for all.

Every donation, whether in money or supplies, designated for a special country has been sent to the country specified. The Austrian Red Cross reported to the American Ambassador in Vienna that one case received by it was intended for France and wished for instructions on what to do with it.

In handling thousands of cases, it is not strange that a box should go astray. In this case, another box was added to the next French shipment from the undesignated eases to replace the one sent to Austria by mistake.

President Wilson, as president of the American Red Cross, added his appeal to that of the boards. In reply to these appeals, money soon began to be received, not as rapidly, however, as the funds that had been sent to the Red Cross in the past for great disasters.

For this, there were various reasons. Americans were stunned by the war, and many resented it. It threatened serious business depression and caused much suffering from a lack of employment at home. Still, society was never hampered by any lack of necessary funds.

At the outbreak of the war, all shipping became so uncertain that even the United States Government was compelled to send men of war to Europe to render aid to our citizens and to prepare several large army transports for passenger service.

Because of this situation and the complications due to the changing of open ports in the early days of the war, the Red Cross found it advisable to secure its ship. None was offered free of charge except one by the Hamburg-American Line.

Fortunately, Congress was in session and promptly passed a law permitting the ship to register from New York, fly the American flag, and take the name of the "Red Cross." This was against all precedent, but barriers of precedent broke away before the appeal of the Red Cross.

In the meantime, through the aid of one proficient in war relief work from her devoted service during the Spanish-American war, Mrs. William K. Draper, secretary of the New York Red Cross Chapter, there was obtained a very generous loan of a large warehouse from Mr. Irving T. Bush, at his Brooklyn terminal, for the collection of supplies.

For days, car after car unloaded the vast store of supplies into this immense warehouse. Hundreds of bales in long rows, hiding beneath burlap and iron bands, the cotton to dress such innumerable wounds, brought a sense of horror to those who gazed at this mute evidence.

Women throughout the country were already organizing into societies to roll bandages and make hospital garments and refugee clothing. These began to accumulate at the warehouse.

At Red Cross headquarters, a special department for advice, patterns, samples, and the little Red Crosses to be sewn on the garments had to be created to answer thousands of inquiries and requests.

While the important work of collecting supplies was proceeding, the Medical Bureau and Nursing Service were occupied with the personnel. The Medical Bureau had not yet perfected its plans to enroll medical men for active service.

At that short notice, it was not easy to secure surgeons of experience and ability so situated as to leave their private practice for a long foreign tour of duty. Because of the question of neutrality, the War Department was unwilling to permit army surgeons to undertake this special service.

It is difficult for people not familiar with the Red Cross and the status of the medical service in times of war to grasp the absolute neutrality of both. Major Patterson, the army medical officer detailed as Chief of the Red Cross Medical Bureau, labored earnestly to overcome the difficulties on his way and was fortunate in obtaining many faithful, able, and excellent surgeons. However, a few were not up to the high standard of the Red Cross.

These surgeons were provided with the regular forest-green uniform of our Red Cross service approved by the War Department. Each unit had a surgeon director, two assistant directors, and twelve nurses, one of whom acted as supervising nurse.

Preparations

The organization of the Nursing Service that Miss Delano had developed with more than six thousand enrolled graduate-trained nurses proved its splendid efficiency. Utilizing the local committee, volunteers from this service were called for and selected from among the number who offered those of the units.

Only American-born surgeons and nurses were sent to avoid confusion about passports and questions of neutrality. The nurse's uniform, consisting of a blue hat, cape, sweater, six wash dresses, ten aprons, four caps, and six collars, and her equipment of a heavy brown blanket and a duffle bag (for trunks were not permitted), cost less than $40.

Later, heavy coats were provided in the colder climates, and in Serbia, special vermin-proof uniforms after the outbreak of typhus fever. Every surgeon and nurse were required to pass physical examinations and be vaccinated for smallpox and typhoid.

Miss Helen Scott Hay, who was to sail for the organization of the training school at Sofia, could not do so as the war postponed the plan, and, therefore, she was sent as the superintendent of nurses. Miss Hay has since gone to Sofia and is now assisting the Queen in organizing the training school there.

Practical instructions as to their personal welfare and caution against sending in their letters any information that the countries they serve might not wish to give out were issued to the nurses. The serious obligations they had to assume and the honor of the American Red Cross and their country entrusted to them for the faithful fulfillment of their duties were strongly emphasized.

War conditions perplexed those who had the ship problem to solve. The officers were obtained from the retired personnel of the United States Navy, and Admiral Aaron Ward, formerly Naval Attaché at Paris, Berlin, and Petrograd, took charge of the arrangements in Europe, joining the ship on her arrival at Falmouth.

At the last moment, certain diplomatic questions arose over the nationality of some of the crew. Nothing was to be done by the American Red Cross that was unacceptable to the countries it sought to aid. Therefore, the sailing was delayed until everything could be satisfactorily adjusted. "Why was money wasted in decorating the ship?" was one of the many strange questions that puzzled Red Cross officers. What decorations were meant?

Finally, it was discovered that painting her white with a broad red band and the Red Cross on the smokestacks were thought to be decorations. The Treaty of The Hague extends to naval warfare, and the Treaty of Geneva provisions stipulate that such ships should be painted white with a red streak and fly the Red Cross flag.

The hospital ships of belligerents are painted white, but to distinguish them from the ships of the Red Cross Societies, the former have a green streak instead of red but fly the same insignia.

The so-called decorations of our Red Cross ship were done in obedience to a treaty obligation and to protect her with these neutral colors. This was not the first time our American Red Cross had sent forth ships of mercy carrying succor to those in need, but never before had one set sail under war conditions. On all previous occasions, the Red Cross flag had been flown only to announce their mission as no protection was required.

Then came busy days loading the large accumulation of supplies when even the stevedores labored on Sunday to complete the work. Those for each country were stored away in reverse order, England's last, and with hers Russia's, as those for Petrograd had to go with the personnel across England, the North Sea, Norway, Sweden, the Gulf of Bothnia, and Finland before reaching their destination.

Next came France, and the ones to be loaded first were Belgium, Germany, and Austria, which were landed at Rotterdam, the last port. "With each unit went an army surgical equipment, and these the doctors were instructed to keep with them, as personal baggage, for a surgeon without his instruments was a useless individual in days when every instrument was already in demand, and there were not enough.

Shocking stories of operations performed with ordinary saws and knives, supplemented by automobile tools, and without anesthetics made one shudder over the unnecessary sufferings and eager to rush the greatly needed supplies across the water.

The White Ship of Mercy

When the date of sailing was decided, the local committees were sent notices to forward to the selected nurses, telling each what day to arrive in New York and what hour to report at the New York Red Cross office to be supplied with equipment; certain hours being assigned to each group of avoid confusion. The entire corps mobilized promptly according to instructions.

It was found impossible to send the ship to the Mediterranean, so the Serbian unit went by Greek ship to the Piraeus and thence to Saloniki. Good courage and uncomplaining spirit were shown by every member of this little group that sailed on September 8th on a long, slow voyage by a second-class ship loaded with a large cargo and more than a thousand Serbian reservists.

It was not clean; there were no baths for the nurses, and the usurpation of their staterooms by the rats compelled some of them to sleep on deck. It was all in a day's work, and neither the Director, Dr. Ryan, who had known the horrors of Mexican revolutions, nor Miss Gladwin, the supervising nurse, who had seen war in the Far East, uttered a protest.

This spirit, manifested by the entire group, promised the splendid service they would later perform.

The Wearers of The Brassard

On Saturday, September 12th, down the busy, peaceful waters of the North River glided the "Red Cross," lining her rails were long rows of surgeons in their green uniforms and nurses in grey gowns and dark blue capes. The beautiful white ship with her band of red, the fluttering emblem of the Red Cross at her foremast, and the American flag (presented by the City of Baltimore) at her stern proclaimed her mission of mercy.

The groups on the boats cheered her on as she passed. The flags of many nations flying from great steamers dipped their colors in salute. No matter what nationality, all were united in wishing her Godspeed on her voyage, and every heart that watched her was touched with the divine light of mercy.

As the white ship passed the towering statue in the harbor, Liberty, for a moment, seemed to grasp in her uplifted hand the flag of the Red Cross that floated at the masthead and to hold it forth a token of America's sympathy for war-stricken Europe.

Life On Board

Life on board was not to be a lazy existence but a busy one of active practice for future duties. Major Patterson demonstrated to the surgeons the use of the field army equipment and drilled them in its employment.

The nurses were divided into many classes, and certain hours were set aside for lessons and practice. The treatment of wounds, bandaging, and practical exercises were carried out under the surgeons as instructors. Lessons in the metric system and languages were part of their studies.

Adopting European customs, the nurses dropped the formal use of the last name and took the gentler one of "sister." Max Mueller says the old Aryan word for sister meant comforter. If this be true, no name better suits the calling of these devoted women.

The Questioning Searchlight

The good ship was not to go unquestioned, and on the first night out from New York, a signal of inquiry came from a watchful British cruiser. Ready with her answer, the red lights in the shape of the Geneva Cross flashed back the message of her mission.

In the name of suffering humanity, she sailed on her way without let or hindrance. Again and again, as she approached the carefully guarded English coast, battleship, and cruiser, she asked the question, and again, the answer granted her safe conduct to her destination.

Arrival At Falmouth

The British Government had designated Falmouth as her English port. A dozen surgeons and fifty nurses landed the units for England and Russia while lighters took the bales and boxes of supplies on shore.

So accustomed are we to the well-regulated days of peace that we find it difficult to understand the confusion of war's strange condition. Questions not infrequently heard were why our units were not always promptly placed and why they did not immediately have many wounded entrusted to their excellent care.

In reading foreign reports, we find nurses of the belligerents themselves waiting and waiting for definite stations and longing for active duty. In city hospitals, we are accustomed to knowing the average number of daily patients, and staff and nurses are provided for this normal amount, but war presents an entirely different proposition.

A furious battle rages for days in a certain locality, and the nearby hospitals are overwhelmed with the influx of patients. Then, the fighting shifts to another point. Those in the first hospitals mostly recover, and their wards are half empty, the nurses sitting with idle hands.

While the service near the new scene of conflict, formerly with little to do, is now, in its turn, overpowered by thousands of wounded, the endless stream of ambulances deposited at its doors.

Funds And Supplies

Before the "Red Cross" sailed, instructions had been received that Brest was to be her French port, but on her arrival in England, this order was changed to Pauillac, the port of Bordeaux. So, turning westward and then southward, she proceeded to answer the many queries of the sentry ships with the emblem of her service.

At that time, the French Government was established at Bordeaux, and their Admiral Ward founded the President of the French Red Cross, the Marquis de Vogüe, academician, diplomatist, archaeologist, and above all philanthropist, who, despite his more than eighty years, has again taken up the burden of war relief.

His daughter, Viscountess Benoist d'Azy, a representative of the French Red Cross at the Ninth Conference when her husband was Naval Attaché at Washington, is serving as a nurse in a Red Cross hospital near the front. A curious little incident occurred somewhat later.

A former American Red Cross treasurer and Assistant United States Treasury Department Treasurer, Mr. Piatt Andrew, was driving an ambulance for the collection of French wounded. Arriving one day at Dunkirk, he stopped before the doors of a Red Cross hospital to leave his wounded men.

As he carefully lifted out a stretcher, a nurse grasped the handles at the other end. Suddenly, glancing at her, he saw, to his surprise, that the nurse was Madame Benoist d'Azy. How little had either thought as they dined and danced in Washington they would meet again in France in the service of the Red Cross.

From Pauillac, the Red Cross continued her voyage to Rotterdam. After she had left the French port, Great Britain pronounced certain portions of the Channel and North Sea danger zones because of mines, but English officers were on the lookout for our ship, and meeting her, a special pilot was put on board to take her through the perils by sea.

At Rotterdam, she received a most cordial welcome from the good people of Holland. The Royal Consort, Prince Henry, President of the Red Cross of The Netherlands, went on board to show his appreciation of her mission.

The fact that the ship carried aid for the sick and wounded of all nations made an especially favorable impression in Holland because the true spirit of the Red Cross—neutrality—humanity—was thus manifested. Here, the stevedores unloaded the last supplies and would accept no pay for their services.

The stores for Belgium were quickly transported to specially chartered vessels and reshipped to Ghent, arriving there before that city was captured. The surgeons and nurses with the supplies for Germany and Austria were given a special train for Berlin.

Though their English tongue caused occasional glances of suspicion, they had but to show their Red Cross passports to turn the glances of suspicion into those of kindly, grateful welcome. Having fulfilled her mission, the "Red Cross" returned to New York, bringing many American passengers to help defray her expenses.

By this time, shipping conditions were improved, and it became possible to forward additional personnel and supplies by the regular lines. The cold Archangel port, despite powerful icebreakers, was closed during the winter months so Russia could not be reached for many weeks.

Thousands of cases of purchased and donated supplies continued to come into the great warehouse of the Bush Terminal, and as rapidly as possible, these were forwarded.

Figures sometimes tell a story; just a few of these may not be too dull to quote. In less than a year, nearly two million bandages, over a million surgical dressings, more than a million yards of gauze, and nearly a million pounds of absorbent cotton were sent to Europe.

Half a million articles of clothing for the wounded and refugees were made by willing hands. Hospital garments decorated with the Red Cross met with the special favor of the wounded men, who saw in each little cross a message of kindly sympathy from across the water.

In the pockets of some pajamas were stowed handkerchiefs, pencils, picture postcards addressed to the makers, and little American flags that delighted the patients. From the students of Yale and Harvard, our great universities, and other generous donors were a score of ambulances.

More than ten million cigarettes came from manufacturers—a gift more welcome than non-smokers comprehend. What oblivion from suffering the forty thousand pounds of aesthetics carried with them!

What safety from infection, that deadly enemy of the wounded in this present war, was sealed in the many barrels of iodine! What prevention of tetanus, typhoid, diphtheria, and meningitis was held in the thousands of doses of antitoxin prepared and sent!

More than a hundred boxes of drugs, more than fifteen hundred additional instruments, hot-water bottles, ice bags, rubber gloves, and sheets by the thousands found their way to the war hospitals in Europe.

Four field hospitals with tents for patients, staff, operations, and kitchen, with their complete equipment, were bought and forwarded. Into all these and innumerable other articles was a wealth of human sympathy from the rich and poor alike.

The check for many thousands showed the same kind desire to aid the sufferers as the ten cents from the poor Polish woman who spoke no English but smiled at the Red Cross as she dropped her mite into a collection box. The money that was designated has been sent to the Red Cross societies.

The undesignated funds have been used for the purchase of supplies and other needs, for the hospitals where our Red Cross units have been stationed, for the American Ambulance in Paris, to aid the prisoners bureau at Geneva, to transport the wounded from the front, for the Belgian refugees, for hospitals in Turkey, for refugees in Persia, for Jews in Palestine, for the German and Austrian prisoners in Siberia, for Russian prisoners in Germany, for the American Relief Clearing House in Paris, for the British Red Cross Intelligence Department, to aid those blinded by war, and for the Sanitary Commission to Serbia and Montenegro. The American Red Cross has tried to send what was most desired to each country.

The field has been so vast, the need so great, the suffering so appalling, that there must come to our American Red Cross a sense of gratitude that, in this worldwide tragedy, it has not had to labor for our own sick and wounded but has been free to lend its aid to each and all of our fellow nations in distress.

Mabel T. Boardman, "Chapter XIX: The European War and the American Red Cross," in Under the Red Cross Flag: At Home and Abroad, Philadelphia and London: J. B. Lippincott Company, October 1915, pp. 267-279.

Return to Content Links

Great Passenger Ships of the World 1858-1912

This initial volume deals with Ships from 1858-1912, from the first passenger ship of over 10,000 GRT to be placed in service (the Great Eastern) to those unforgettable sister ships, the Olympic and Titanic — the first of more than 40,000 GRT.

Passenger Ships of the World - 1963

🎓 “A Global Voyage Through Steamship History for Historians, Genealogists, and Maritime Enthusiasts”

Eugene W. Smith’s Passenger Ships of the World – Past and Present (1963) is a masterfully curated encyclopedic reference that charts the rise, peak, and transformation of ocean-going passenger ships through nearly two centuries. Expanding upon his earlier Trans-Atlantic and Trans-Pacific works, Smith offers a global maritime panorama that includes ships serving the Americas, Africa, Europe, Asia, Australia, and Oceania, as well as Canal routes and California-Hawaii shuttle lines.

🧭 This book is an essential resource for:

- Maritime historians seeking design evolution and fleet data

- Genealogists tracing voyages and shipping lines

- Educators and students studying transoceanic migration and tourism

- Ship modelers, naval architects, and enthusiasts interested in dimensions, tonnage, and speed

US Steamships: A Picture Postcard History

Over many years, Postcards were collected for the message, history, and the scene. As a result of these collecting interests, we have a valuable source of information relating to many subjects, including steamships, from a historical, technical, and artistic perspective. The Postcards in this book provide a chronological history of U.S. Steamships.

Return to Content Links