US Navy Ship Construction Program

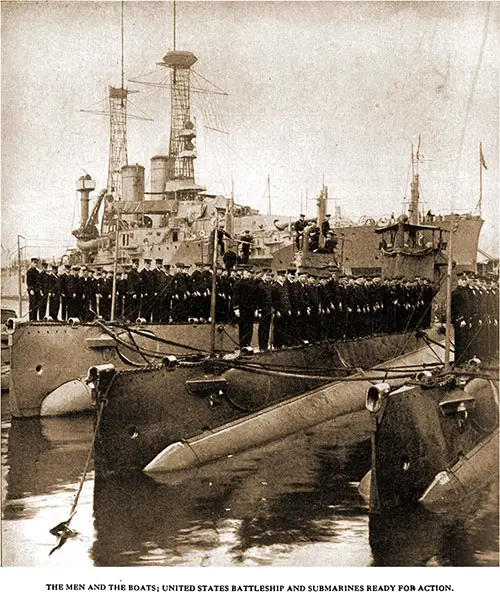

A United States Battleship and Submarines Ready for Action. Leslie's Photographic Review of the Great War, 1920. | GGA Image ID # 1829c25e89

1,000 Ships in Construction Program

Secretary Daniels announced in 1917 that the entire war-building program of the Navy embraced nearly a thousand ships. Most of the vessels authorized by the three-year program of 1916 were contracted for early in 1917; but the necessity of concentrating every energy on smaller craft to combat the submarines and the absorption of shipbuilding facilities, labor, and material in our huge undertaking of building vitally necessary merchant vessels prevented the pushing of work on capital ships which could not be completed in time to be used during the war.

Within a short time after hostilities began, contracts had been made for every destroyer that American yards could build. But the call came for more, and yet more of these swift fighting crafts which had proved the most effective weapons against the submarine. To produce them, new facilities had to be created.

The naval authorities set to work to solve the problem. Congress adopted the recommendations of the Navy Department and, on October 6, 1917, appropriated $350,000,000 additional for the construction of destroyers, the creation of new facilities, and the speeding up of those already contracted for.

That very week the contracts were signed, and work was begun on the enlargement of existing shipyards, the building of new yards, and new factories to produce engines and forgings. The way in which this huge undertaking was carried out was inspiring.

Large New Shipyards Built

Perhaps the most striking instance was the building of the Victory Plant, at Squantum, Massachusetts, where on land that had been almost a swamp, rose in a few months the largest and most complete plant in existence devoted entirely to the building of destroyers; and in April 1918, six months after the ground had been broken for the yard, the keels of five destroyers were laid in a single day.

New records were made in construction, vessels being completed in eight months from the laying of the keels when previously from twenty months to two years had been the usual time required.

In a special instance, to see how quickly it was possible to construct a destroyer, the Mare Island Navy Yard, by "field riveting" and other "hurry up" methods, succeeded in launching the destroyer Ward in 17 1/2 working days after its keel was laid and the vessel was put into commission in 70 days.

On July 4, 1918, no fewer than 14 destroyers were launched, eight of them at a single yard, the Union Plant of the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Company at San Francisco.

The U. S. Navy has built or has under construction or contract more destroyers than any two navies possessed at the beginning of the European war - and our new destroyers are of the most modern type—315 feet long, 28,000 horsepower, with a speed of 35 knots.

The staunchness of our destroyers was proved on many occasions. When the Manky collided with a British steamship, depth-bombs on her rear deck exploded, and her stern was almost blown off, yet she was successfully taken to port, repaired, and put back into service.

The Shaw was cut in two by a collision; the vessel was so badly smashed that it looked like scrap-iron, yet the two parts remained afloat and were towed to port.

Big Battleships Added to the Fleet

At the close of hostilities, there were 655 naval vessels under construction or contract. Four hundred submarine chasers, many destroyers, and craft of other types had been completed and put into service.

The latest additions to the Battle Fleet were the Mississippi and the New Mexico, 32,000 tons displacement, the largest warships in service in any navy.

The New Mexico was equipped with the electric drive, considered one of the greatest improvements of our time in marine engineering. Under test, this proved to be entirely successful, and hereafter all our major ships will be so equipped.

The repair of the 109 German interned vessels was a triumph of American ingenuity and engineering skill. Hoping to prevent the use of these vessels, their crews so badly damaged the machinery that they believed it was beyond repair and that a long period would be required to replace the boilers and engines.

But, by the use of electric welding and of other new methods, all this machinery was repaired, and within little more than six months, the ex-German and Austrian vessels were in service as transports, carrying American troops, munitions and supplies overseas.

North Sea Mine Barrage

Our Navy took a leading part in constructing the North Sea Mine Barrage, the largest work of the kind ever undertaken and an essential factor in the antisubmarine warfare.

This project was proposed by Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, Chief of Ordnance, soon after this country entered the war, but it was not until nearly a year later that the British and American authorities finally adopted the plan and, through their cooperation, put it into execution.

For this project, a new type of mine combining maximum destructiveness with safety in handling was developed; 100,000 of these were manufactured, and a mine-loading plant capable of automatically loading more than 1,000 mines a day was established.

An entire fleet of mine-layers and vessels for transporting mines was organized, manned, and put into operation, Mine Force No. 1, which did the mine-laying, being under the command of Captain Reginald R. Belknap.

56,570 American Mines Laid

Under Rear Admiral Joseph Strauss's command, two bases were established at Inverness and Invergordon on the coast of Scotland, from which the mine-layers operated.

This mine-barrage stretched across the North Sea a distance of 230 miles, from the Orkneys to Norway's coast. It was completed in October 1918.

Of the 70,100 mines planted, 56,570 were American. While the effectiveness of this barrage is almost impossible to determine with exactness, it is believed that less than ten submarines were shattered or sunk, and the danger of running into this mine-barrier greatly increased the difficulties of the U-boats in making their way to the Atlantic.

Naval Railway Batteries in France

When the imperative need of huge guns of long-range for use against the Germans on the Western front was demonstrated, naval ordnance experts pointed out that a number of 14-inch guns originally designed for battlecruisers could be made available for use ashore, and special railway mounts of a new type were designed in less than 30 days.

Work was begun in February 1918, and on April 25, the first gun mounted complete, left the shops for firing tests. Each battery comprised a complete train, with the standard 83-ton locomotive, 562-ton tender, gun-cars, armor-plated ammunition cars; crane car, construction crane, sand, timber, workshop, kitchen, fuel and staff radio cars, berthing cars for officers and men, and battery headquarters.

Several locomotives and 80 cars were built for the battery trains. The guns were the largest ever placed on a mobile mount. They could be placed over the pit foundation ready for firing in a few moments, and in the same space of time could be raised, ready for removal.

Can Fire Projectile 25 to 30 Miles

The first parts were shipped in June to St. Nazaire, France, and there assembled, and on September 25, the guns were put into action on the Western Front.

Tests had shown a possible range of 55,000 yards, about thirty miles. In operation, the gun fires from the rails at angles of elevation up to 15 degrees.

At this elevation, the standard Class * 'B" 1400 pound projectile Ls thrown a distance of 22,450 yards, or 12 8/10 miles, approximately.

The gun is capable of being fired at angles of elevation up to 45 degrees, at which its range is 42,500 yards or a distance of 24 2-10 miles approximately.

Smashed German Bases and Railway Lines

Five of these Naval Railway Batteries, under the command of Rear Admiral Charles P. Plunkett, were in service with the Western Front's armies until the end of hostilities. They were engaged at Montmedy, the last shot being fired at Longuyon the day the armistice went into effect.

These long-range guns, throwing their huge projectiles far behind the German lines, did great destruction to the enemy bases and munition depots, smashing railways and stations and playing their part in cutting off the Germans' main line of retreat.

During the war, the Navy manufactured 2,841 guns of medium calibers, of which 1,887 were placed in service; arming naval vessels and merchant ships, some of our allies' vessels, as well as our own; furnishing mobile land batteries for use ashore, these including six-inch guns placed on caterpillar tractors; produced ample shells and ammunition for all vessels operating under the Navy and accumulated a large reserve supply.

Depth-Charge Used against Submarines

The depth-charge, which proved the most effective weapon against the submarine, was developed from a small, crude "can" carrying 50 pounds of explosive to a huge affair containing 600 pounds of TNT, which could be operated with almost as much safety as any ordinary shell. In the beginning, destroyers carried only four depth-charges; before the end of the war, they were carrying fifty as an average load.

This and the increased safety of handling enabled them, instead of merely firing a single charge against a submarine, to drop a number of depth- bombs covering the entire vicinity, and these depth-bomb barrages proved one of the most important factors in the destruction of U-boats.

A Y-gun was invented for firing depth-charges. Seaplanes were supplied with depth-bombs, by which they could reach submarines underwater, and a non-recoil gun was adopted for use on airplanes.

A new star shell for illuminating enemy vessels without disclosing the position of the ship firing was devised and will, it is believed, greatly increase the effectiveness of firing at night.

Listening devices were developed to determine the approximate position of submarines operating underwater, and ships were equipped with paravenes to sweep up automatically mines encountered in their path.

Vessels Skillfully Camouflaged

Marine camouflage was developed into fine art. From the beginning of the war, the question of painting vessels in such a manner as to prevent their being seen, or to enable them to escape the submarine attack, was carefully studied.

This is by no means the same as "camouflage" as it is generally understood on land, where objects at rest are painted or marked in such a manner as to prevent their being identified against a fixed background.

Experience showed that no system of marking will materially reduce the visibility of a vessel; that a uniform coat of paint is about as good as anything for the purpose of reduction of visibility, but unfortunately, the most desirable color varies with conditions.

Experiments carried on for years in our service indicated "battleship gray" as the most desirable color for all-around purposes, which was confirmed by war experience.

"Dazzle" Painting System Developed

There was developed, however, a system of so-called "dazzle" painting—the vessel being painted grotesquely and bizarrely for the purpose, not of rendering it invisible but rendering it difficult for the submarine commander, peering through his periscope for a few seconds at a time, to determine the course of the vessel.

While not always effective, there is no doubt that dazzle painting is a palliative against submarine attack. Its application, not only to naval vessels but to all vessels of the Emergency Fleet Corporation, was systematically undertaken.

A division was formed in the Bureau of Construction and Repair, which undertook the preparation of the designs for American vessels, which were painted in accordance with the designs supplied, and more than 1100 vessels were camouflaged in various designs.

John Wilber Jenkins, Our Navy's Part in the Great War, New York: John J. Eggers Company, Inc., 1919, pp. 42-46.