German U-Boats on American Coast - 1918

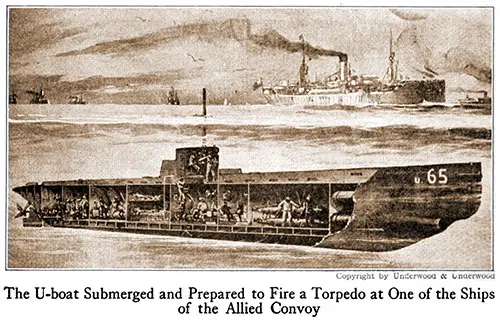

U-Boat U-65 Submerged and Preparing to Fire Torpedo at a Ship in an Allied Convoy. Photo © Underwood & Underwood. Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume 11: Child's Book of the War, 1920. GGA Image ID # 17ffba2e5c

From the beginning, it was realized by the American naval authorities that Germany could at any time send her submarines across the Atlantic, and patrol vessels in home waters were constantly on the lookout for them.

But it was not until the latter part of May 1918, more than a year after we entered the war, that they finally appeared.

The first indication of their presence was finding the schooner Edna off the Delaware coast floating like a derelict, with holes in her bottom that had evidently been made by bombs.

The crew was gone, and there was no way of finding out just how the schooner had been disabled. Later it was discovered that the crew had been taken aboard the submarine and held prisoners to avoid discovery.

The Edna had been stopped by the U-boat about 2 o'clock, the afternoon of May 25. Earlier the same day, the schooners Hattie Dunn and Hauppauge had been sunk by bombing, and their crews taken aboard the "sub."

Sank Five Vessels in One Day

It was not until June 2 that the submarine disclosed its presence. That day, it appeared off the New Jersey coast; at 8 o'clock in the morning, sank the schooner Isabel B. Wiley, 12 minutes later, sank the Winneconne, at noon sank the schooner, Jacob Haskell, at 3 P. M. the schooner Edward H. Cole, and at 4.40 P. M. sank the sugar-laden steamer Texel; finishing the day by sinking the passenger steamer Carolina at 6:45 P. M.

Thirteen lives were lost in the sinking of the Carolina, the most serious loss of life in the submarine operations in these waters. The next day the submarine sank the schooner, Samuel Mengel, off the Delaware coast. Then, going south, it sank the schooner Edouard R. Baird and the steamer Eidsvold on June 4.

The same day the French steamer Radioline reported she was being pursued; a destroyer went to her assistance and fired at long distance at the enemy, which submerged and escaped.

On June 5, some distance at sea from the North Carolina coast, the British steamer Harpathian and the Norwegian steamer Finland were sunk.

The next day the Mantella, a British steamship, was sent down, and on the 8th, the Pinar del Rio, an American steamer loaded with sugar, was sunk by gunfire.

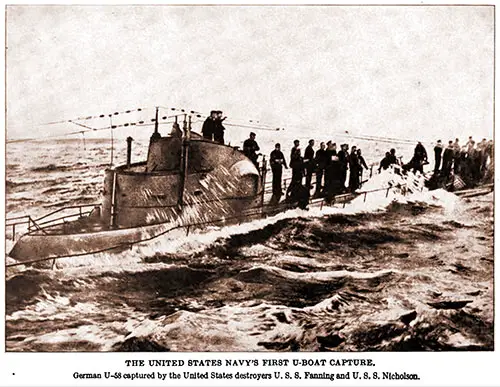

The United States Navy's First U-Boat Capture. German U-58 Captured by the United States Destroyers USS Fanning and the USS Nicholson. German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast, 1920. GGA Image ID # 18003d27c1

Crew of the USS Fanning That Sank the U-58 Submarine. The Star on the Funnel Indicates a Submarine Victim. Our Navy at War, 1922. GGA Image ID # 180368716f

Sank Steamers on Return Voyage

The "sub" moved further out to sea, and two days later, the Norwegian steamships Vindeggen and Henrik Lund were bombed and sent to the bottom.

On the 14th, the Norwegian barks Samoa and Kringsjaa were sunk, the former by bombs, the latter by gunfire. The U-boat then headed for Germany.

Far out at sea, the British steamship Dwinsk was torpedoed on June 18. The first submarine which operated in American waters was found to be the U-151.

In addition to attacking vessels, floating mines were strewn at various points. The Herbert L. Bratt, an oil steamer, struck one of the mines near Delaware Breakwater and was sunk, but was quickly raised, towed to port, and repaired.

Cruiser "San Diego" Sunk by Mine

Later these enemy mines caused the loss of the largest American naval vessel sunk during the war, the cruiser San Diego, which, on July 19, struck a mine below Fire Island and sank in a few minutes.

The mine exploded on the port side just aft of the forward port engine-room bulkhead. The feed tank and circulating pump were blown in, and the port engine wrecked.

"Full speed ahead" was rung, and the starboard engine operated until it was stopped by water rising in the engine-room.

Machinist's Mate Hawthorne, who was at the throttle in the port engine-room, was blown under the engine-room desk. He got up, closed the throttle on the engine, which had already stopped, and then escaped to the engine- room ladder.

Lieutenant Millen, on watch in the starboard engine-room, closed the water-tight door to the engine-room and gave the necessary instructions to the fire-room to protect the boilers.

Captain Climbed Down Side of the Ship

The ship listed to port heavily so that water entered the gun-ports on the gun- deck. She listed eight degrees quickly, then hung for seven minutes; then gradually listed, the speed increasing until 35 degrees was reached.

At this time, the port quarter-deck was three feet underwater. The ship then rapidly turned turtle and sank. Captain H. H. Christy went from the bridge down two ladders to the boat deck, slid down a line to the armor belt, then dropped down four feet to the bilge-keel, and thence to the docking-keel, which at that time was eight feet above the water.

From there, he jumped into the water. The ship was about five minutes in turning over after she reached 35 degrees heel.

No wake of a torpedo was seen. The first thing Captain Christy noticed was while standing on the wheelhouse, eight feet above the forward bridge, lie felt, and heard a dull explosion.

He immediately sounded submarine defense quarters and the general alarm. Everything went quietly and according to the drill schedule.

The captain rang full speed ahead and sent officers to investigate the damage. At the time, he thought the ship would not sink. Two motor sailors were ordered rigged out but not to be lowered until further orders.

Stood by Guns Until Deck Was Awash

At the submarine defense call, the men went quietly to their stations and manned the guns. They stood by the port guns until they were awash, and by the starboard guns until the list of the ship pointed them up into the air.

When it seemed obvious that the vessel would capsize, the order was given to abandon ship, except the port side gun-crew, which were to remain at their stations as long as the guns would bear.

Boats were ordered lowered, and two sailboats, one dinghy, one wherry, and two punts were launched. The life rafts were launched, and the lumber pile on deck was loosed and set adrift.

Fifty mess tables and a hundred kapok mattresses were thrown overboard. "Abandon ship" was complete before the vessel began to capsize.

Men Cheered and Sang National Airs

Perfect order was preserved, the men cheering. When on the rafts, they sang. "The Star-Spangled Banner" and "My Country. 'Tis of Thee," cheered for the captain, the executive officer, and the ship, and cheered when the U. S. ensign was hoisted on the sailboat.

Two dinghies, with six officers and 21 men, pulled to shore and landed at 1:20 P. M. Three steamers that were in the vicinity rescued the other survivors and took them to port. Six lives were lost in the sinking of the San Diego, and six men were injured.

Raided New England Fishing Fleet

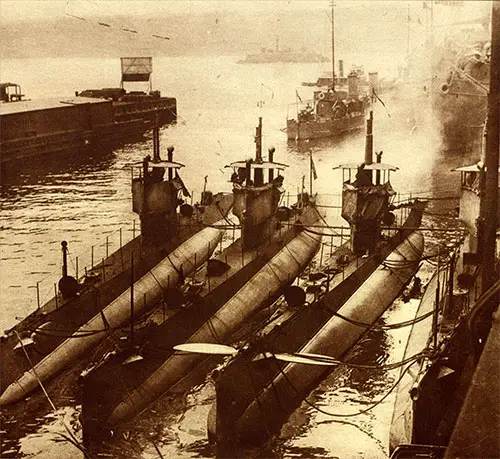

American Submarines of the K-Class Fitted out with Machinery and Equipment of the Latest Type to Be Used in Case of Hostile Descent on Our Coast. Photograph © Central News Photo Service. The War of the Nations, New York Times, 1919. GGA Image ID # 195d22b592

The enemy submarine activity was resumed in July. August 10, a German submarine appeared among the fishing fleet off the New England coast and sank a number of small fishing craft.

On one occasion, the enemy ventured close to the coast, and off Chatham, Mass., shelled a tug and four barges in tow, wounding several persons that were aboard. Naval aircraft attacked the "sub," which submerged and went further out to sea.

A submarine also appeared in southern waters, sinking a number of schooners off the Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia coast, and going as far south as North Carolina, where it gunned and sank the lightship at Diamond Shoals.

Several steamships were also sunk. But the submarines did not venture to attack convoyed vessels, kept out of the way of destroyers and patrol craft, and in a few weeks, their activities ended and were not resumed.

Couldn't Stop Sailing of Transports

Though many small sailing craft and a number of steamers were sunk, the submarines failed to attain the military object of their raids in these waters, which, as was well known, was to strike terror to Americans and stop the steady stream of troops and supplies going to France.

When they first appeared, Secretary Daniels said: "The first duty of the Navy is to keep open the road to France; to guard our transports and supply ships; to keep moving the Stream of troops and supplies being sent overseas.

Every protection possible was being given to coastwise commerce and sailing craft, but the Navy never for a moment lost sight of the main military object.

The transports' sailing was not delayed for a day, they were carefully guarded, and not one was lost or even attacked as it left our ports.

John Wilber Jenkins, Our Navy's Part in the Great War, New York: John H. Eggers Company, Inc., 1919, pp. 38-41.