A Merrie English Christmas Dinner - 1911

The Wife Brings the Plumb Pudding to the Dining Table Where the Family is Assembled for a Delightful Chrismas Dinner. Country Life, December 1904. | GGA Image ID # 2029e712eb

Christmas is a time of feasting in Old England, and preparations are made for the dinner as far ahead as November; the first work is usually done during the week before Advent.

The church of England collects for the Sunday before Advent commences with the words "Stir up, we beseech thee," and this is known by many as "Stir-up Sunday," the housekeeper often remarking, after her return from service, "Well, this is 'Stir-up Sunday.'

I must begin to make the mincemeat and plum pudding."

But, in the dinner itself, the mincemeat and plum pudding comes towards the end rather than the beginning, so we must consider the more substantial parts of the repast first. As a general rule, the dinner begins with hare soup, and making this is quite a task.

To quote Mrs. Glasse, of culinary fame, "First catch your hare," and when caught, have him skinned, cut up into joints, wash thoroughly, and place in a large saucepan or stewpan, together with two carrots, two onions, a bay leaf, a little celery, and whatever soup herbs are obtainable.

Add two quarts of water and cook slowly over the fire or in the oven—the last-named method commonly employed in England.

The cooking must continue for several hours until the meat is quite tender; then strain the soup through a coarse sieve to keep back the bones and meat, and season to taste with salt, black pepper, and a tiny ground clove; thicken slightly with cornstarch, rubbed smooth with cold water (a tablespoonful of cornstarch to a quart of soup).

Mince Meat Pie in a Glass Pie Plate. Business of Being a Housewife, 1917. | GGA Image ID # 202a22ff73

Have ready some forcemeat balls made by blending a cup of stale bread crumbs, a tablespoonful of chopped parsley, a teaspoonful of poultry dressing, one-third of a cup of finely chopped beef suet, salt, and pepper to taste; bind these ingredients with a lightly beaten egg, form into tiny balls and cook ten minutes in a hot oven, add them to the soup just before serving.

Fish is rarely served at Christmas dinner, the main meat course following the soup, and consists of a baron of beef, which is the two porterhouse roasts together. If possible, these are cooked on a spit in front of an open fire and served with dish gravy.

A roast-sucking pig sometimes takes the place of the beef. The pig should be only three or four weeks old and must be cooked as soon as practicable after being killed.

It is thoroughly scalded, well washed and cleansed, stuffed with a poultry dressing made of sage, onions, bread crumbs, and seasonings, with a bit of butter or chopped suet.

The stuffing is sewed into the pig, which is afterward trussed and skewered into shape as though lying at full length. It must then be roasted for about three hours, continually basting during the cooking and flouring lightly about half an hour before it is done.

The tongue of the pig is served on a separate dish, having been removed before cooking and then boiled, as are the liver, heart, and feet. These are all seasoned, minced, and dressed with parsley, sweet herbs, and butter. After roasting, the pig is often divided down the center of the back before being dished. This is for the convenience of the carver.

England is less rich in vegetables than the United States. Still, potatoes browned around the roast will be served with mashed turnips, creamed onions, and applesauce.

As a general rule, turkey is not served at the English Christmas Dinner, which is reserved for the New Year feast, but chicken pie made the same as ours is frequently found, mainly where the chief joint is roast beef.

An English dinner table also needs to include the many little side dishes to be found here, the foods being heavier and more substantial, though not as many as is customary in this country.

A favorite salad is the one known as "Benares," which is made from chopped apples, celery, grated coconut, peppers—either fresh or canned—and finely chopped parsley.

Everything Needed to Make Mayonnaise Dressing. American Cookery, 1917. | GGA Image ID # 202a4e2189

These are all blended and marinated with a French dressing. A little mayonnaise is sometimes used with this salad for decorative effect. Still, the primary dressing is the French one, made with four tablespoonfuls of olive oil, one and a half tablespoonfuls of vinegar or lemon juice, a little mustard, salt, and pepper, all beaten together with a fork until they emulsify.

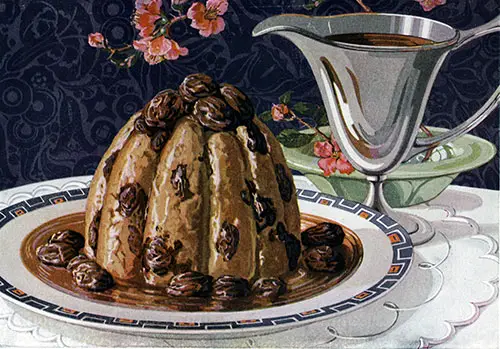

And now, from the children's point of view at least, comes the main feature of the dinner, the pudding.

The lights—for the well-appointed Christmas dinner is always served by artificial light, even though it may be a midday meal, as it usually is, for the convenience of the family's younger members—have been carefully lowered. All eyes are turned to the door.

A slight crackling noise is heard, and the pudding is brought in, enveloped in flames, which threaten to consume the beautiful piece of holly, with the large berries stuck into the top of the pudding.

It is usually so rich a pudding that it almost falls to pieces at a touch, and the wonder is how the cook ever got it out of the mold and upon the platter without breaking.

An old family recipe states that such a pudding should be made from the following ingredients:

- One pound each seeded sultana raisins and currants,

- half a pound of mixed candied peel—orange, lemon and citron—

- half a pound of blanched and chopped almonds,

- half a teaspoonful of ground cloves,

- one teaspoonful of ground cinnamon,

- half a grated nutmeg,

- a quarter of a teaspoonful of allspice,

- half a teaspoonful of salt,

- one pint of breadcrumbs,

- one cupful of flour,

- one pound of sugar,

- ten eggs,

- one pound of finely chopped beef suet and

- One cup of grape juice.

All the ingredients must be thoroughly mixed, and tradition has it that every family member must take a hand stirring the pudding. After mixing, divide it into portions, for these quantities will make enough for three or four good-sized puddings.

Place in well-greased molds or bowls, cover closely, either with the lid of the mold or with a floured cloth that has been wrung out of boiling water, and steam the puddings for ten hours as it then requires only enough cooking to heat it through at the time of serving or about one hour.

The water should never be allowed to come to the top of the molds when steaming the pudding. A kettle of boiling water must be in readiness all the time to replenish that in the saucepan containing the puddings, as if cold water, or even ordinarily hot water, is used for this purpose; there is likely to be a heavy streak through the puddings.

Traditional English Plumb Pudding with Hard Sauce. American Cookery, December 1912. | GGA Image ID # 202a5b723f

English Plum Puddings are often made one year before they are used. It is no uncommon sight in a country house to see two or three of them suspended from the rafters of the kitchen or storeroom in company with the home-cured hams and bacon.

In addition to the plum pudding, mince pie is also in evidence on the Christmas table, not the large family pie, such as we serve here, but individual ones, for there is a theory that everyone must eat twelve mince pies between Christmas and the New Year if they would have luck during the succeeding twelve months, and if the pies were made as large as we are accustomed to seeing them the luck would probably belong to the family physician, rather than to the eater of the pastry.

It is said that the first mince pies were made by an old Lady who had unexpected company the day after Christmas. She had plenty of substantial food to place' before them but no dessert.

Part of a cold plum pudding was the only available thing, and she hastily chopped it up, enclosed it between crusts of pastry, baked it, and—behold! The first mince pie! It was so successful that she improved the formula, which has come to our ever-popular mincemeat.

The English rule for this is One pound each of currants, raisins, sugar, chopped suet, chopped apples, half a pound of chopped mixed peel, the same of nuts or almonds; one teaspoonful of ground cinnamon; one teaspoonful of ground ginger, a quarter teaspoonful of ground cloves, one grated nutmeg, the grated rind of two lemons, one cupful of grape juice. Other fruits may be added to these ingredients at discretion, while the liquid from canned fruits is often added as this gives both moisture and richness.

Meat is only used to make real English mincemeat, if we may call it suet meat.

As in the case of the plum puddings, mincemeat improves by moderate keeping and, in any case, should be made four or five weeks before it is needed so that it may ripen. A good crust, flaky or puff, should be used in making mince pies; otherwise, the moisture of the mincemeat is apt to render it heavy and soggy.

Wine jelly is usually in evidence on the dinner table, but is there more for the sake of appearance than because it is needed, for even the veriest dyspeptic breaks through his diet rules on Christmas day and boldly eats both pudding and pie, regardless of indigestion which may follow.

Delicious Raisin Pudding with Sauce for the Holidays. Woman's Home Companion, February 1921. | GGA Image ID # 202b02d201

As a general rule, dessert in fruits, nuts, and raisins comes after the pudding. Even when dinner is served at midday, no other set meal follows. However, the young people make merry with roasted chestnuts and snapdragons when they have somewhat recovered from the effects of their dinner.

The nuts are, of course, roasted on the bars of an open grate, occasionally turned to allow all sides to cook evenly, and are eaten while hot.

Snapdragon is a thoroughly English institution and consists of placing raisins on a platter, pouring over them a little alcohol in some form, setting fire to it, and then having the different members of the family pick the raisins from the dish while the flames are still burning.

This is always done in the darkness, and the burning alcohol casts weird shadows over the room and the faces of those around the table.

Monkman, Elizabeth, "As Christmas Dinner is Served in Merrie England," in Table Talk: The American Authority Upon Culinary Topics and Fashions of the Table, Cooperstown, NY: The Arthur H. Crist Co. Vol. XXVI, No. 12, December 1911:652-654