SS Elbe Archival Collection

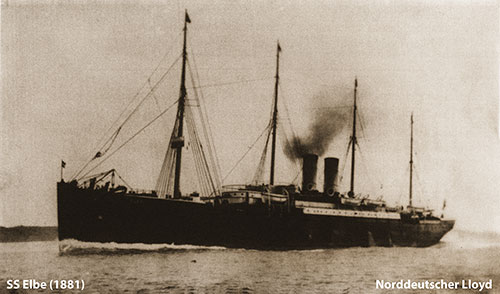

Norddeutscher Lloyd SS Elbe (1881) At Sea. | GGA Image ID # 1dd9fd7272

Elbe (1881) North German Lloyd

Built by John Elder & Co., Glasgow, Scotland. Tonnage: 4,897. Dimensions: 418' x 44' (440' o.l.). Single-screw, 17 knots. Compound engines. Four masts and two funnels. Iron hull. Hurricane deck amidship was 180 feet long. It was used as a promenade deck for first class passengers. Maiden voyage: Bremen-Southampton-New York, June 24, 1881. Passengers: 179 First, 142 Second, and 796 Third/Steerage class. Fastest Time from Southampton to New York, 8 days 1 hour in 1882. This famous North Atlantic liner was transferred to Bremen-Australia service in October 1889. Fitted with electric lights in 1883. Fate: Sunk by collision with British steamer SS Crathie off the Dutch coast in the North Sea, 31 January, 1895, and sank in 20 minutes with the loss of 332 lives. Only 20 of the 352 souls on board survived. Sister ships: Fulda and Werra. Note: The first express steamer of the Norddeutscher Lloyd was the SS Elbe.

Return to Content Links

Brochures

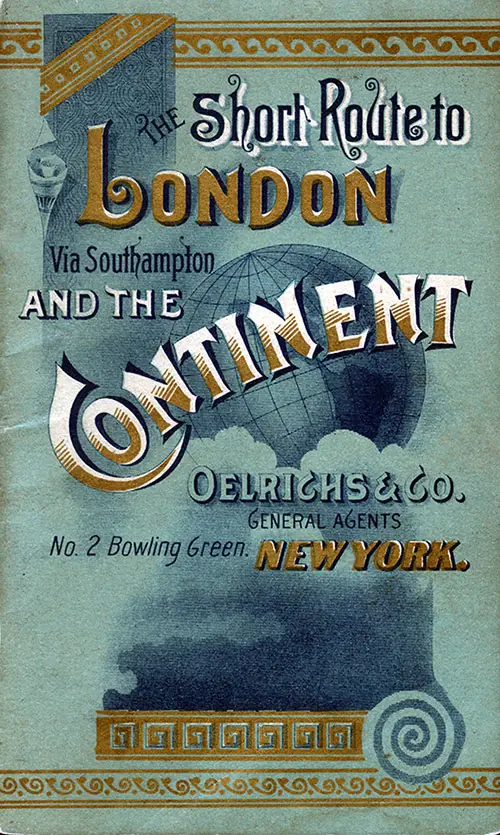

North German Lloyd - Short Route to London - 1889

🎓 “A 19th-Century Ocean Travel Brochure Turned Educational Goldmine”

The 1889 North German Lloyd (NDL) brochure titled "The Short Route to London via Southampton and the Continent" is more than a promotional travel pamphlet—it is a remarkable cultural artifact that opens a window into late 19th-century transatlantic steamship travel. Created during the Paris Exhibition of 1889, this richly detailed guide was distributed by Oelrichs & Co., the line’s New York agents, and served as both a functional passenger handbook and a marketing showcase for NDL’s first and second cabin services.

Teachers, students, genealogists, and historians will find the brochure incredibly valuable for understanding the social, economic, and technological structures of the Gilded Age’s oceanic travel system.

Return to Content Links

Sheet Music

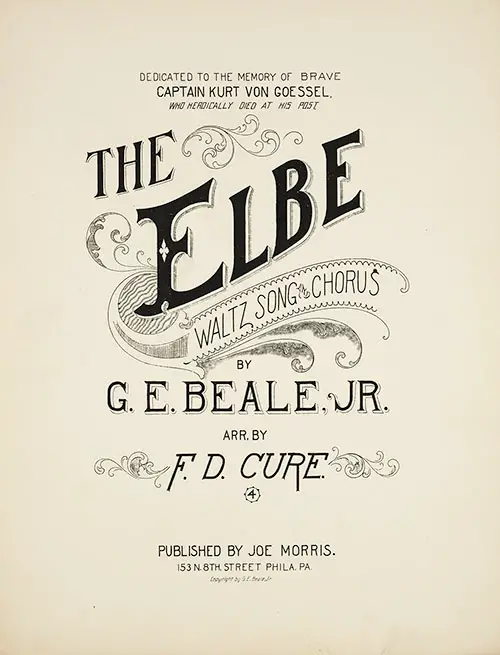

The Elbe: Waltz Song and Chorus, Dedicated to the Memory of Brave Captain Kurt von Goessel Who Heroically Died at his post. Music by G. E. Beale, Jr. Arranged by F. D. Cure. Published by Joe Morris, Philadelphia. © 1895. | GGA Image ID # 1dda4865a0

Advertisements

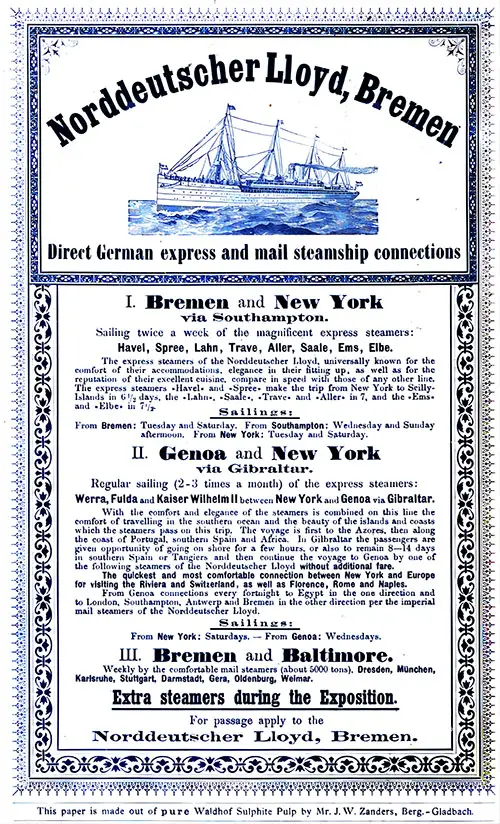

Advertisement (1893): Norddeutscher Lloyd German Express Mail Steamship Connections Promoting the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. | GGA Image ID # 227ffc1844

I. Bremen and New York via Southampton.

Sailing twice a week of the magnificent express steamers: Havel, Spree, Lahn, Trave, Aller, Saale, Ems, Elbe.

The express steamers of die Norddeutscher Lloyd, universally known for die comfort of their accommodations, elegance in their fitting up. as well as for die reputation of their excellent cuisine, compare in speed with those of any other line. The express steamers - Havel- and - Spree- make the trip from New York to Scilly Islands in 6½ days, the -Lahn-, - Saale-, -Trave- and - Aller- in 7 days, and the -Ems- and -Elbe- in 7½ days. Sailings: From Bremen: Tuesday and Saturday. From Southampton: Wednesday and Sunday afternoon. From New York: Tuesday and Saturday.

II. Genoa and New York via Gibraltar.

Regular sailing (2-3 times a mouth) of the express steamers: Werra, Fulda and Kaiser Wilhelm II between New York and Genoa via Gibraltar.

With the comfort and elegance of the steamers is combined on this line the comfort of travelling in the southern ocean and the beauty of the islands and coasts which the steamers pass on this trip. The voyage is first to the Azores, then along the coast of Portugal. southern Spain and Africa. In Gibraltar the passengers are given opportunity of going on shore for a few hours, or also to remain 8—14 days in southern Spain or Tangiers and then continue the voyage to Genoa by one of the following steamers of the Norddeutscher Lloyd without additional fare.

The quickest and most comfortable connection between New York and Europe for visiting the Riviera and Switzerland, as well as Florence, Rome and Naples.

From Genoa connections every fortnight to Egypt in the one direction and to London, Southampton. Antwerp and Bremen in the other direction per the imperial mail steamers of the Norddeutscher Lloyd.

Sailings: From New York: Saturdays. — From Genoa: Wednesdays.

III. Bremen and Baltimore.

Weekly by the comfortable mad steamers (about 5000 tons).

Dresden, München, Karlsruhe, Stuttgart Darmstadt Gera, Oldenburg, Weimar.

Extra steamers during the Exposition.

For passage apply to the Norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen.

Collision of the SS Elbe with the SS Crathie - 1895

The two vessels collided on January 30th, 1895, in the North Sea. Enough was said in the public press at the time of the disaster to make any reference to the sad loss of life unnecessary.

Except for the fact that the SS Elbe was a passenger vessel and her loss involved the terrible sacrifice of 334 human lives, the disaster differed very little from collisions that occur almost daily in crowded waters. Such an event passed unnoticed by the general public because it is "only a tramp," and a few more unfortunate sea toilers have gone to the bottom.

The facts may be briefly stated as follows: The Crathie, a 475-ton steamer trading between Aberdeen and Rotterdam, left the latter port at 11 p.m. on January 29th. The night was dark but clear and freezing. The wind was E.N.E. and strong, with a heavy sea that came over the forecastle head.

At 5.20 a.m. the following morning, during the mate's watch with the lookout on the lower bridge and while steering N. by W. W. magnetic, all three lights of the North German Lloyd's SS Elbe have sighted two points on the starboard bow three or four miles away.

Almost immediately, the Elbe shut in her red, but subsequently, when only three or four lengths distant on the starboard bow, opened it again. The Crathie struck her fairly on the port side, just abaft the engine-room bulkhead.

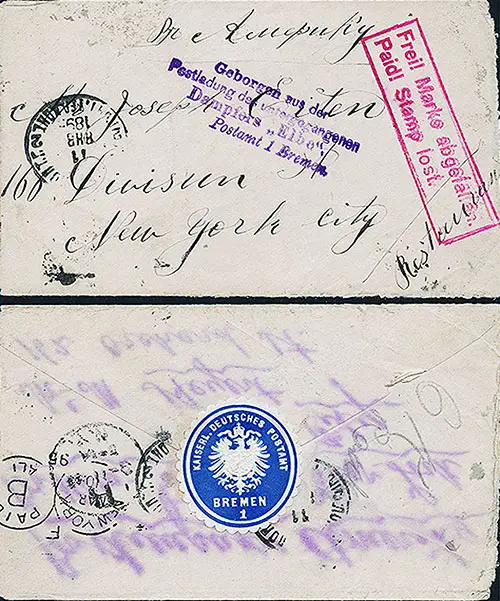

Letter Salvaged from the Sinking of the SS Elbe, 1895. | GGA Image ID # 1dda4e0c47

With neither vessel slowing down, the Elbe was so severely damaged that she sank in a mere twenty minutes. The survivors, all in one boat, were rescued by the smack Wildflower and brought to safety at Lowestoft.

After swiftly clearing away wreckage to prevent further damage, the Crathie embarked on a two-hour search. Unfortunately, it found nothing and had to return to Rotterdam for repairs.

The North German Lloyd's Company, since the loss of their steamer SS Elbe, has been besieged by inventors with plans for lowering boats. It is said that the Company has at length made arrangements for supplying the whole of its fleet with a system by which "a boat may be lowered in ten seconds."

If this new system can lower a 32-ft. lifeboat in ten seconds, it could be a game-changer. Shipowners should take note, though it's important to remember that the real test is not in the controlled environment of a dock but in the unpredictable conditions of a rolling ship in rough seas.

Return to Content Links

Lowestoft's Elbe Inquest - 1895

Testimony of Pilot Greenham, Miss Boecker, and Crathie Captain

LONDON, 26 February 1895.—The Coroner's inquest upon the bodies of the Elbe victims brought ashore by fishing boats was resumed at Lowestoft this morning. Miss Anna Boecker, the only woman survivor of the Elbe, the English pilot Mr. Greenham, and the crew of the steamer Crathie were present.

Capt. Donner was in attendance on behalf of the German Government, and lawyers representing the owners of the Elbe and the Crathie were present. Capt. Gordon of the Crathie was also present.

Pilot Greenham testified that after the crash, he saw attempts to close the Elbe's watertight doors. Capt. von Goessel was on the bridge until the last. When he got to the deck, he saw that the Elbe had lost its port rockets, but its blue lights burned, and its siren was blowing.

The Captain ordered the boats to get out, but the ropes were frozen and had to be chopped away. The orders were obeyed, and there was no confusion. When Greenham got into the boat, he saw a green light and a white stern light, which he believed to be the lights of the colliding vessel. These lights disappeared southward.

He said the speed of the Elbe at the time of the collision was sixteen miles an hour. She would go some distance before she ran her way off after her engines were stopped—the steamer he had seen stopped at the time of the collision. However, until after daybreak, it was only possible for those aboard to see a lifeboat with a light.

Mr. Greenham said he burned paper in the boat to attract the attention of the colliding vessel and expressed his belief that if the men on the Crathie had kept a good lookout, it would have been possible for them to have seen the light.

Capt. Gordon, commander of the Crathie, took the stand and testified that when the wreckage was cleared away from the Crathie's bows, the ship was turned around to go after the Elbe. About three-quarters an hour after the collision, the Elbe steamed away.

Miss Boecker was called to the witness stand and confirmed her previous statements. She could not say whether the Elbe's engines had stopped when she went on deck.

Both the Captain and the chief engineer of the Crathie deposed that the vessel's telegraph was frozen at the time of the collision. The engineer admitted that he had yet to see whether the telegraph was all right when the ship sailed from Rotterdam. Orders were given to the lookout man, who shouted them to the engine room.

On the conclusion of the engineer's testimony, the Coroner intimated that the inquest would be adjourned until 26 March. The solicitor for the Captain of the Crathie I objected to this proposal and asked that the jury render a verdict. It would be cruel, he said, to let the matter hang fire over the Captain's head for a month. The Coroner opposed the rendering of a verdict at present, and the inquest was adjourned.

It has been decided to limit the inquiry to events after the collision. No investigation will be made into the cause of the disaster because of the proceedings in that direction, which are pending in Rotterdam.

Return to Content Links

The SS Crathie and the SS Elbe - 1895

AFTER a lapse of four and a half months from the date of the disaster, judgment has been given in the Board of Trade inquiry into the circumstances attending the collision between these two vessels on January 30th in the North Sea.

Enough was said in the public press at the time of the disaster to make any reference to the sad loss of life unnecessary.

Except for the fact that the Elbe was a passenger vessel and that her loss involved a terrible sacrifice of human lives, the disaster differed very little from collisions that occur almost daily in crowded waters and which pass unnoticed by the general public because " only a tramp " and a few more unfortunate sea toilers have gone to the bottom.

The facts may be briefly stated as follows: The Crathie, a steamer of 475 tons trading between Aberdeen and Rotterdam, left the latter port at 11 p.m. on January 29th. The night was dark but clear and very cold, with strong wind E.N.E. and a heavy sea coming over the forecastle head. At 5.20 a.m. the following morning, during the mate's watch with the lookout on the lower bridge and while steering N. by W. W. magnetic, all three lights of the North German Lloyd's Elbe have sighted two points on the starboard bow three or four miles away.

Almost immediately, the Elbe shut in her red, but subsequently, when only three or four lengths distant on the starboard bow, opened it again, and the Crathie, despite the mate's order " hard a port, " struck her fairly on the port side, just abaft the engine-room bulkhead.

Neither vessel had slackened speed, and the Elbe was so seriously injured that she sank in twenty minutes, the survivors, all in one boat, being picked up by the smack Wildflower and landed at Lowestoft.

The SS Crathie, after clearing away wreckage to prevent further damage, cruised about for two hours, finding nothing back to Rotterdam for repairs. The collision has been the subject of exhaustive inquiry.

An inquest was held at Lowestoft, a German investigation was conducted, and the Board of Trade inquiry was conducted in London. A lawsuit between the owners is pending in the Dutch Courts. Obtaining the German evidence for the London inquiry was somewhat difficult.

Still, all the material witnesses, except the Elbe lookout, were ultimately secured. To the questions submitted by the Board of Trade, the Court, which consisted of Mr. Marsham, Captain Castle, Captain Richardson, and Captain Kiddle, R.N., gave the following answers:

1. The Crathie's engine-room telegraph was not working when she left Rotterdam since it was frozen. It appears not in proper working order at the time of the collision. However, the Court believes the collision was not traceable or affected by its condition.

2. The watch on deck (on the Crathie) at and after 4 a.m. on January 30th was insufficient for the ship's safe navigation. The Court attaches no blame to the master for this but considers there were insufficient deckhands.

3. The Court is not satisfied that either the mate or lookout man (on the Crathie) left their posts and went into the galley during their watch on deck on the morning of January 30th or that either of them was absent from the bridge between about 5 a.m. and the time of the collision.

4. The vessels were "crossing vessels " within the meaning of Article 16 of the Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea. The Crathie did not comply with Article 16 of the Regulations since she did not keep out of the way of the Elbe on the starboard side. She did not comply with Article 18, for she did not slacken her speed or stop until after the collision. The Elbe did not comply with Article 18, for she did not slacken her speed nor stop when there was a danger of collision. She did comply with Article 22.

5. A good and proper lookout was not kept on board the Crathie. A good and proper lookout was kept on board the Elbe.

6. The officer in charge of the Elbe acted quite rightly in keeping her on her course at full speed until there was danger of collision. Still, as soon as that was apparent, he should have blown his whistle and stopped his engines, which, in the opinion of the Court, might and ought to have been done in time to avoid the collision. The Court holds that the officer in charge of the Crathie was primarily to blame for the collision by not keeping a good lookout. It seems likely that it was averted by the officer in charge of the Elbe stopping his vessel as soon as he perceived the danger of collision.

7. The master (of the Crathie) was justified in being in his cabin at the time of the collision and could not form a clear opinion as to the damage done to the Elbe, which was a much larger vessel than his own; he saw a rocket from the Elbe and answered it with two blue lights, after which the Elbe burnt a red and blue light in succession. There was no further intimation of the state of the Elbe. His first duty was to attend to the safety of his vessel, which was seriously damaged. He had to clear away some wreckage that was hanging under her bottom and extricate from it a man who was injured by it, which took half an hour; two of her plates were pierced, and water was coming through them into the cabin, and there was a high sea, rendering it dangerous to lower a boat, insomuch that one of the Elbe's lifeboats, which was much larger than any of his, was swamped in launching. He stood by from about 5.30 a.m. until the break of day and, as he thought, saw the Elbe turn round and disappear toward the Thames. The Elbe's boat was not visible to him. Under the circumstances, the Court believes that the master complied with the provisions of section 422 of the Merchant Shipping Act 1894.

8. The Crathie was not navigated with proper and seamanlike care.

9. The Crathie's mate, Robert Henry Craig, alone is in default, and the Court cancels his certificate.

From this, it will be seen that the collision was typical in its causes. A small trader, with a minimum crew, whose time at sea is a brief interval between spells of cargo working, crosses the track of an express liner.

The former has a bad lookout and neglects her duty to give way; the latter, with the strongest disinclination to alter her course or slacken speed, holds on despite danger, and a collision follows.

There were faults on both sides, but the more significant blame lay with the Crathie. A blast from Elbe's whistle might have saved the ship. Still, it was not given, the only explanation being a miscalculation of the distance consequent on the dimness of the Crathie's green light.

The case in these respects does not differ from a hundred others. Preventing the recurrence and the increase of such disasters is one of the most challenging problems of the day.

A standard of colors for lights might do much, a manning scale perhaps more, but there has been no cure yet invented to keep a look- on the alert at his post when he is dead tired and half froze.

Return to Content Links

Bibliography

"Collision of the SS Elbe with the SS Crathie," in The Nautical Magazine, 1895.

New York Times, "Lowestoft's Elbe Inquest," 27 February 1895.

"The SS Crathie and the SS Elbe," in The Nautical Magazine and Journal of the Royal Naval Reserve, London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Limited, Vol. LXIV, No. VII, July 1895. pp. 657-659

Return to Content Links