A Picture That Stirred A Nation - Archibald Willard Spirit of '76 Painting

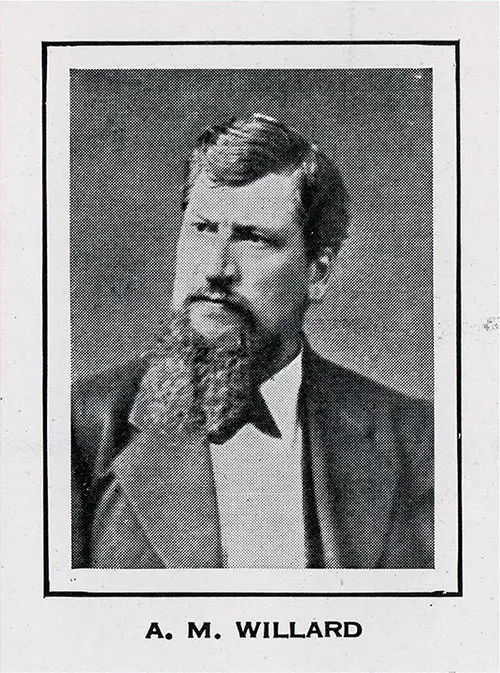

Archibald M. WILLARD. | GGA Image ID # 135123bb98

ARCHIBALD WILLARD died some years ago, but his soul, like that of John Brown, still "goes marching on." He painted it on canvas for all of us to see, and it is called "The Spirit of '76." The painting is not a notable contribution to art.

When it was first exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in 1876 it created no enthusiasm in the art world; no critic hailed it as the work of a new genius; no art lovers burned incense before it. But every man, woman and child that cherished the simple, rock-bottom principles of patriotism greeted the picture with a quickening heart-beat.

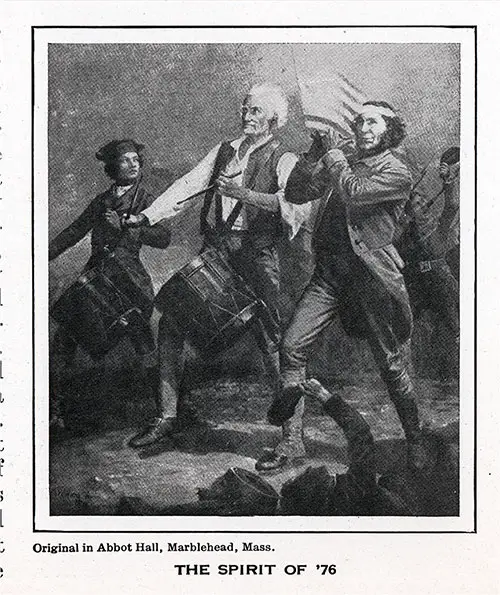

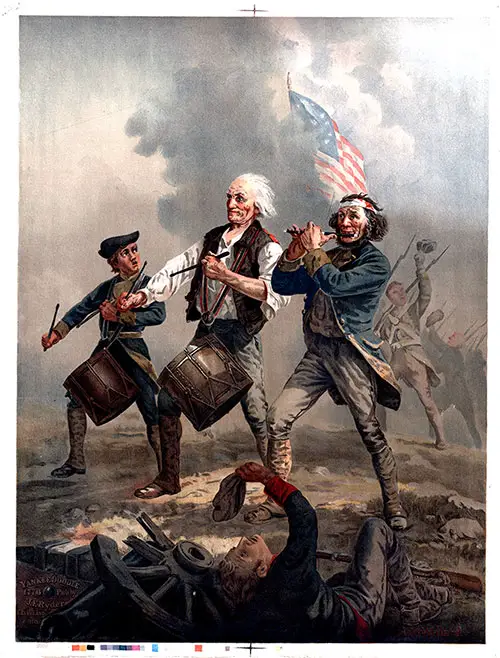

In the figures of the white-haired old man, the sturdy fifer, and the boy, marching fearlessly forward with drum and fife and waving flag, all the people, old and young, saw three generations of a nation's protest, and they thrilled at the spectacle so vividly set before them.

THE SPIRIT OF '76 Painting by Archibald M. Willard. Original In Abbot Hall, Marblehead, Mass. GGA Image ID # 13516816e9

The story of the painting is a very simple, human one. The artist's name is Archibald M. Willard, and he was born at Bedford, near Cleveland, Ohio, August 22, 1836. He had little art training in his early years, or later, but he had a certain facility with pen and brush, and while camping near Cumberland Gap, he made pictures of that picturesque military situation, which, being photographed, were purchased by his comrades and their friends as mementoes of army life.

Willard returned from the war with a great plan in mind. He would represent on large sheets of canvas the war scenes he had witnessed and sketched, and exhibit them throughout the North.

He studied art for a while, and then labored long on a great panorama mounted on rollers, which he undertook to exhibit in northern towns, but the plan was not a financial success. In the end, he Washed the color out of the cotton cloth, to save at least that part of the investment.

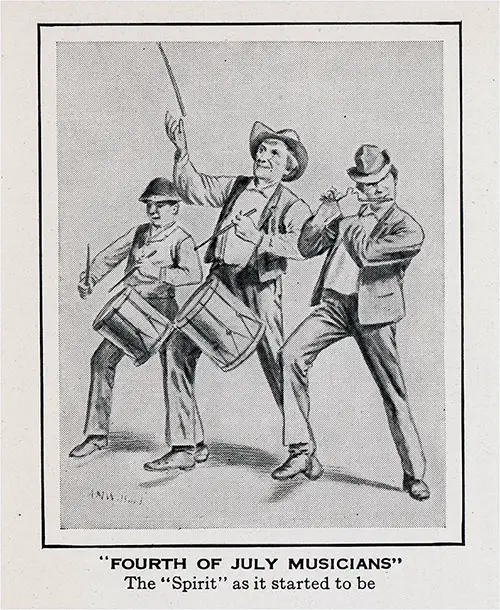

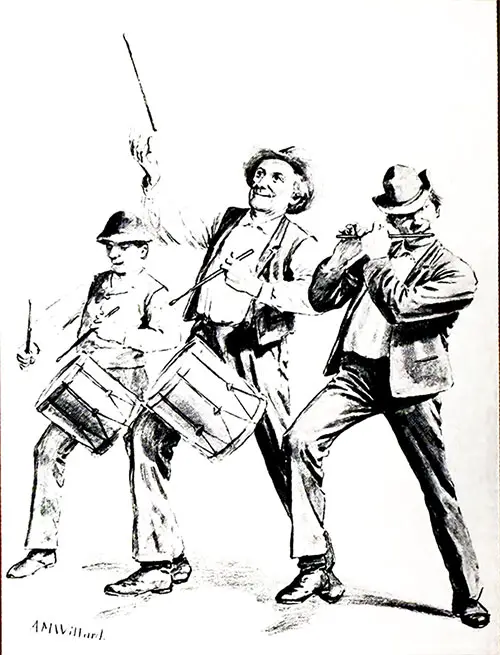

FOURTH OF JULY MUSICIANS" - The "Spirit" as it started to be. GGA Image ID # 135177c67a

Willard then curbed his ambition, and got a plain job as a painter in a carriage shop. Willard's wagons and carriages won attention and favor because of the little paintings he often put on the side to catch the eye of the purchaser. Many a sale was made by his employer, because of these adornments.

Willard's father was a country minister, and his grandfather a Revolutionary soldier—so religion and patriotism, and love of fun were all his by inheritance—and it was the last of the three that first expressed itself in his attempt at art.

One day the daughter of his employer brought him a crude wood-cut of a dog harnessed to a wagon, chasing a rabbit, and asked him to paint her a picture like that. Using the wood-cut as a suggestion, he painted a picture called "Pluck." It showed a dog hitched to a cart chasing a rabbit, and in the cart, two frightened children, with hair rising on end, hanging grimly to the seat and reins.

When this picture was exhibited in a Cleveland photographer's window, many people stopped to look at it, and its fame spread far and wide through reproductions.

This, and a companion picture, done in chromo process, were sold by thousands. Willard now had enough money to apply himself exclusively to picture making, and sketches of a humorous nature came in rapid succession from his brush.

Many of his comics were printed in the newspapers and reproduced by lithography. He illustrated John Hay's "Jim Bludsoe," and he made an amusing picture, "Deacon Jones's Experience," that delighted Bret Harte so that the latter gave the picture its title and wrote a poem to go with it.

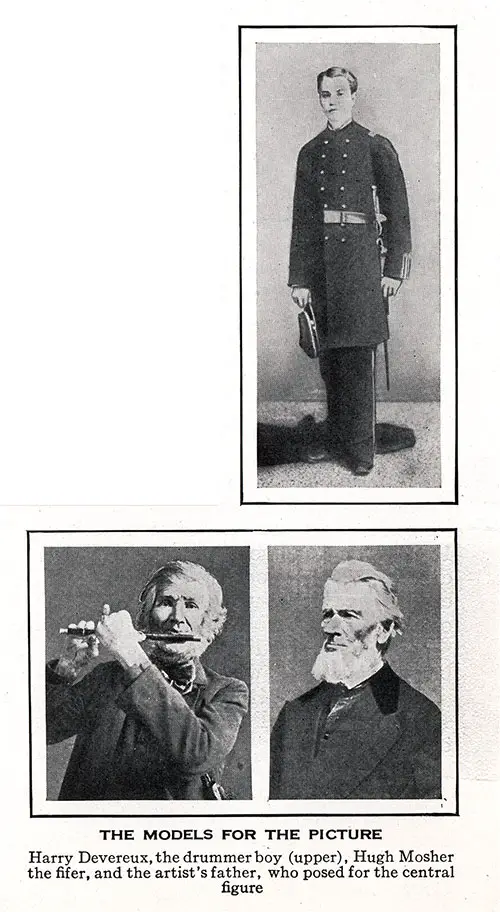

THE MODELS FOR THE PAINTING "The Spirit of '76". Harry Devereux, the drummer boy (upper), Hugh Mosher the fifer, and the artist's father, who posed for the central figure. GGA Image ID # 135198a985

As the Centennial Exposition of 1876 was approaching, Willard was anxious to make a picture that would be suitable for exhibition there. He had the idea of painting a group of country musicians at a Fourth of July celebration.

He recalled a jolly old drummer who had a reputation for tossing his drum sticks nimbly, and creating mirth in general while marching at the head of country parades.

Then it occurred to Willard that he could make a pictlire that would excite patriotic enthusiasm if he transferred his trio of country musicians to the battlefield. He threw aside his humorous sketches, and began to paint the picture called "Yankee' Doodle" or "The Spirit of '76."

His own father, a gray-haired Baptist minister, posed with the drum for the central figures Hugh Mosher, a farmer soldier who had blown his fife through the Civil War, was chosen as the fifer of the painting.

He was the most famous fifer for miles around, and was always in demand at patriotic celebra tions. The picture caught and stirred the people at sight.

In the face of destiny the sturdy old man and his two companions marched on, oblivious to the fact that they marched alone. In the dim distance, the flag waved, and the column was rolling up.

The army had rallied, and was following to the tune of °Yankee Doodle." Altogether it made a rousing public appeal, and there was a wide demand for copies of it.

At the close of the Philadelphia exhibition, the picture was bought by General Devereux for his home town of Marblehead, Massachusetts, and there, in Abbot Hall, it still hangs.

The purchase was a matter of sentiment, as well as art interest, for General Devereux's son, Henry Devereux, was the model for the young drummer boy in the picture.

Probably no other patriotic picture painted in America has had so wide a circulation as "The Spirit ot '76." It is known in every city, town and village, where it can be seen in frames, and on calendars, posters and mailing cards. It belongs now to the people—a picture in thousands of houses.

Willard continued to make sketches, with patriotic interest or with child life as their theme, until he passed away at his home in Cleveland, on the eleventh of October, 1918.

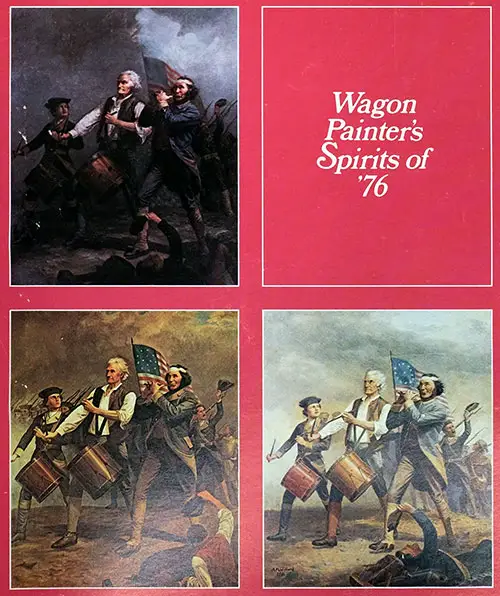

At First He Called It Yankee Doodle

Three most notable of several versions of “The Spirit of '76" painted by Archibald Willard are Marblehead's (top, in the Selectmen's Room, Abbot Hall); Cleveland's (left, in City Hall), and Wellington's (right, in the Herrick Memorial Library). GGA Image ID # 1351fb2c71

The choice of the “Spirit of 76“ for the Nation’s first Bicentennial stamp would not have surprised Archibald Willard, the former carriage and wagon painter who created the canvas a hundred years ago.

To Willard, the work expressed a timeless theme: “[it] was not painted in commemoration of 1776 or 1876, or any other special period in the life of our Nation, but as an expression of the vital and ever-living spirit of American patriotism.“

The artist was relatively unknown when he entered his painting in the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, where it achieved the popularity that has continued to this day.

Born on August 26, 1836, in Bedford, Ohio, Willard was the grandson of an old Green Mountain Boy who was with Gen. John Stark when Burgoyne surrendered at Saratoga, and the son of a Baptist minister who left Vermont early in his life to settle in Ohio. His father’s ministry later took him from Bedford to Wellington, Ohio, which he always considered home.

Willard’s artistic bent expressed itself early. As a child, ‘‘Arch” drew pictures on fences and barn doors, and he even had a few lessons from an itinerant portrait painter.

But small towns such as Wellington provided little opportunity for an artist, and at 17 he took up the closest thing he could find to an art career—a job striping and decorating wagons and carriages at the E.S. Tripp Carriage Works.

Tripp built fine landaus and phaetons as well as farm wagons. Willard was soon doing nearly all the handpainted medallions on the carriage dashboards and the colorful decorations on the sides and tailgates of the wagons.

He was also painting pictures. A Wellington street scene he painted in 1857 suggests that by his early 20’s he was already a skillful artist, although his style was rather primitive.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Willard and his three brothers enlisted in the Union army, and the young artist served as a color sergeant in the 86th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The brothers saw 4 years of hard service, and all returned home safely. With nothing better in sight, Willard returned to the Tripp Carriage Works.

His first big break came in the early 1870’s, when he created a humorous painting to amuse Addie, Tripp’s young daughter. The work showed a child’s wagon with a dog hitched to it, the dog chasing a rabbit, and a boy and girl holding on as another boy tumbles off the rear. Willard called it “Pluck.”

James F. Ryder, a Cleveland photographer and art dealer, saw the painting and recognized its potential as a chromo, or color print, a popular novelty made possible by the development of commerical chromolithography in the 1860s.

In those days, books were illustrated mostly with steel engravings, and newspapers were illustrated with woodcuts, if at all. This new process enabled printers to reproduce pictures in full color, and many of them were making the most of the new mass market.

Ryder was in a position to have these reproductions made and distributed, and found the subject matter of ,,Pluck,, ideal for this purpose: it was colorful, mildly humorous, and properly sentimental in its view of childhood.

Thinking that a matched set of chromos might sell better than a single picture, he asked Willard to do a companion piece showing a happy ending to the adventure. “Pluck No. 2” has the wagon overturned by a fallen log, the rabbit caught, and the children sprawled on the ground, unhurt.

Ryder’s estimate of public reaction was accurate. Nearly a thousand of the chromos were sold at $10 a set, something more than a week’s pay for a working man.

How much Willard received is not reported, but it was enough to enable him to give up his job at the carriage works and become a full-time artist. Encouraged by Ryder, he went to New York in 1873 to study briefly with J. A. Easton.

On his return to Ohio, he moved his family from Wellington to Cleveland and set up a studio in his home, and began to search for humorous subjects for chromos.

He found one in Wellington on the Fourth of July. This was muster day for the militia, and the holiday observance culminated in a parade in the village square. Willard watched one high-spirited group of two drummers and a fifer clowning as they marched, with one drummer tossing his sticks in the air and all three bumping in good-humored confusion.

Willard's original humorous drawing, which he sketched on the back of an envelope and called “The Fourth of July Musicians" or "Yankee Doodle," is in The Wellington Collection. At the suggestion of an enterprising photographer, Willard switched to a patriotic theme, making several rough Sketches of his trio in a Revolutionary War battlefield setting. Eventually, lithographs popularized the former wagon painter's Centennial masterpiece throughout the country. GGA Image ID # 13524e5c20

Willard sketched the group on the back of an envelope and showed the drawing to Ryder. He called his sketch "The Fourth of July Musicians" or "Yankee Doodle." It might well have sold as a chromo, but Ryder had a better idea. The Centennial of the Revolution was approaching, and there were already signs of increased interest in American history.

Ryder suggested that Willard forget the humor and paint a serious patriotic scene.

The artist worked out the Revolutionary War battlefield setting in a series of rough sketches. The older drummer no longer tossed a stick in the air but marched grimly forward, hatless and in shirt sleeves.

The fifer's hat became a bandaged head, and the second drummer became a young boy, gazing admiringly at the old man. A wounded solider lying in the foreground raised his hat to a flag waving in the haze behind the indomitable trio of musicians, who were advancing to spark a rally in the face of threatened defeat.

Archibald Willard's “Spirit of '76,” exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, is in Abbot Hall, Marblehead, Mass. It was this canvas that was used as a model for the Nation's Bicentennial stamp. Yankee Doodle 1776. Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-05936. GGA Image ID # 1352875dc6

Next came the actual painting, as Willard fleshed out the small sketch on an 8- by 10-foot canvas. He had no trouble getting models. His father, the Rev. Samuel Willard, a veteran of the War of 1812, posed for the white-haired central figure.

For the fifer he chose Hugh Mosher of Wellington, a lowering 6 1/2-foot wartime companion who had served as a fifer in the army. A Wellington neighbor, Charles Spicer, served as the model for the wounded soldier in the foreground.

For the second drummer, Willard remembered a boy he had seen barking out orders to a cadet company in a competitive drill in Cleveland: Harry Devereux, captain. Third Company, Brooks Military School. It was a fortunate choice.

The battle scene was imaginary and the flag an anachronism, since the Stars and Stripes pictured was not authorized by Congress until 1777 and was not actually used in the field until later than that. But such matters did not bother Willard, if he knew of them.

When the canvas was finished, it was displayed in the window of Ryder’s photographic studio. Crowds came to see it, and Ryder had prints made which spread its fame throughout the country.

Although Willard had not done the painting with the Centennial Exposition in mind, Ryder and other friends of his hoped it would be shown there. The Centennial Commission planned to display only the best of classical art from the major art centers of Europe and the United States, but its members found it difficult to argue art quality when large numbers of people were arguing patriotism. Eventually, they sent a telegram to Willard, asking him to bring his picture to Philadelphia.

The “Spirit of ’76” turned out to be the most popular work of the exposition, drawing large crowds and counting among its admirers President Ulysses S. Grant, who saw it during a hurried tour and was impressed enough to return later to study it at his leisure.

After its triumph at Philadelphia, the painting was bought by Gen. John Henry Devereux, a railroad president and the father of the drummer boy, who sent it on an extended tour of the country. On its return, Devereux had it installed in Abbot Hall, the public building he had built as a gift to his hometown, Marblehead, Mass., where it remains today.

That wasn’t the end of the “Spirit of 76” for Willard, however. He painted at least six slightly different versions during his lifetime, including one for the City of Cleveland in 1912, when he was 76, and a smaller version for Wellington’s Herrick Memorial Library dated 1916, when he was 80. He died in Cleveland on October 11, 1916. Cleveland calls its painting the “masterpiece” version. It is on display in the rotunda of City Hall.

It is estimated that Willard did 400 paintings in his lifetime There are 40 owned by the people o! Wellington and kept in the Herrick Memorial Library Collection; non; 17 are traveling with the Wellington collection exhibit. More can be learned about in Wellington, for some of the buildings associated with his career are still there. Those who knew the wagon painter believe he translated with his brush the feelings of patriotism he experienced during long walks and talks with his grandfather about the Revolutionary War. Main Street — which Willard painted in 1857— has, of course, changed; but two white, Greek Revival houses remain from the days when the township was a railroad hub in the center of a cheese producing area.

The houses are included in a 12- acre site of 57 downtown structures named to the National Register of Historic Places. Today, Wellington has a do-it-yourself Bicentennial project coordinated under the New Spirit Wellington Committee, which includes representatives from every organization in the community.

The Wellington collection of Willard’s paintings has been displayed in connection with the American Revolution Bicentennial in several cities across the Nation under sponsorship of the Diamond Shamrock Corporation, whose headquarters are in Cleveland.

In addition to the final oil and preliminary sketches of the celebrated “Spirit of 76,” the collection includes Willard s “Blue Girl" portrait, “The Old Mill,” “River Scene,” and other portraits and landscapes.

When the Postal Service’s Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee took up the subject of a stamp to open the Nation’s Bicentennial year, there was no doubt that the “Spirit of ’76” would be selected. Neither was there much difficulty about which of the 14 versions to use.

Art members felt that the original painting bought by Gen. Devereux and given to Marblehead after its showing at the Centennial Exposition—although perhaps technically less finished than Cleveland’s "masterpiece” version—was a much more vigorous work.

Where to place the stamp (actually three stamps placed side by side to show the figures to best advantage) on first-day sale was a problem, with Marblehead, Cleveland, and Wellington all vigorously pressing their claims. The Postal Service sidestepped the choice by placing the stamps on sale on New Year's Day at booths along the route of the Tournament of Roses parade.

First-day sales of stamps, something of an index of popularity, were well over a million, which suggests that even in the cynical age of Vietnam and Watergate the "Spirit of |’76” has not lost its appeal for millions of Americans who may not know much about ait. but know what they like.

"A Picture That Stirred a Nation," in THE MENTOR, Volume 9, Number 6, July 1, 1921, Pages 36-37.

Belmont Faries, "At First He Called It Yankee Doodle," in Worklife: U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Vol. 1, No,. 7, July 1976, P. 33-37.