Motion Pictures Industry - 1920s

This series presents a history and discusses the birth of films and the motion picture industry. Profusely illustrated and educational.

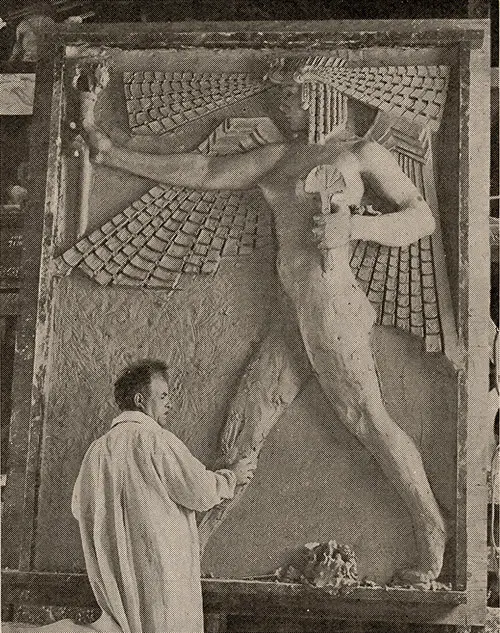

Finn Haakon Froelich, an Eminent Western Sculptor, Modeled One of the Decorations Used in a Mammoth Film Spectacle. This Is an Example of How Artists Are Called In To Beautify and Dignify Motion Pictures. The Mentor, 1 July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9dfd7994

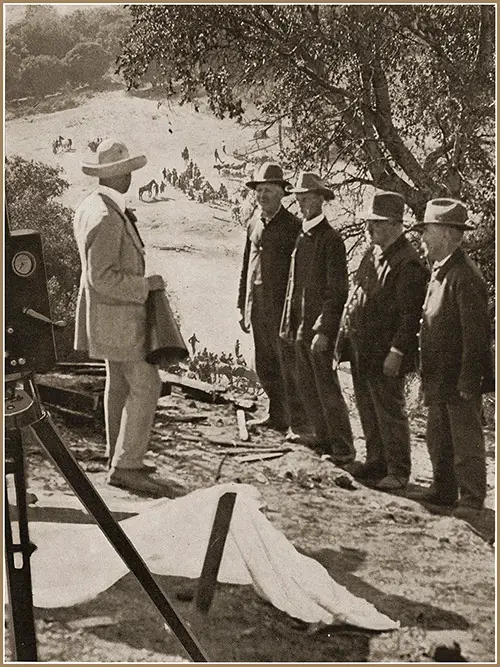

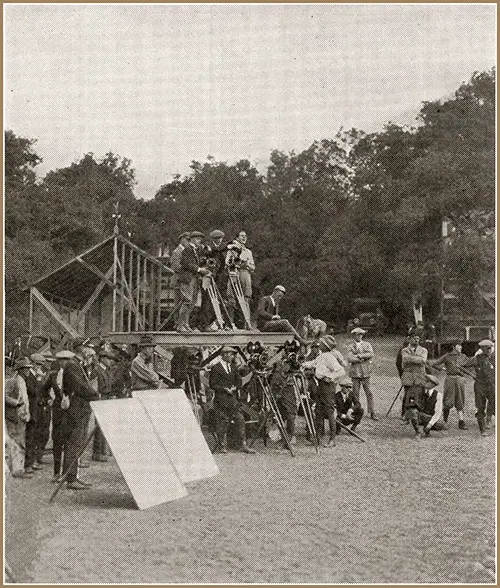

A Historic Moment In Motion Pictures - D. W. Griffith

D. W. Griffith, Setting His Natural Stage for a "Long Shot" in His Epoch-Making Photoplay, "Birth of a Nation." The Long Shot Was Invented by Griffith and First Used in This Picture. The Director Is in Consultation With Civil War Veterans to Ensure the Accuracy of the Battle Scene He Is About to Film. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c95f09323

Motion Pictures: Four Epochs

Motion Pictures: The Miracle of Modern Photography By D. W. Griffith, Creator of "Birth of a Nation," "Hearts of the World," "Broken Blossoms," and "Way Down East."

Soon after releasing my first war picture, " Hearts of the World," I received a letter from an eminent historian. I shall always treasure the letter, especially for this paragraph:

History must be divided into four epochs: The Stone Age, The Bronze Age, the Age of the Printed Page—and the Film Age. You have produced a vital human record in a single picture that embodies the war's spirit and soul with a more profound reality than all the books combined.

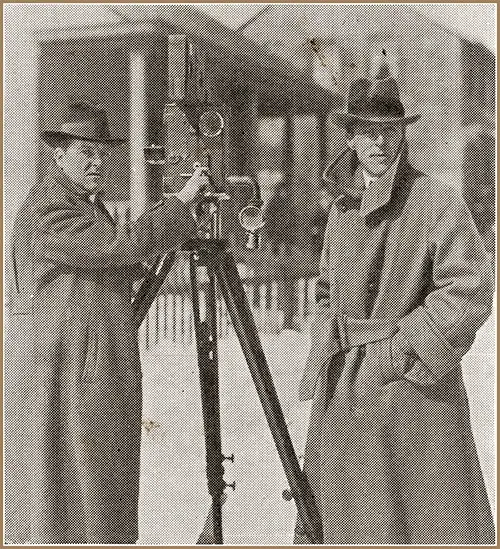

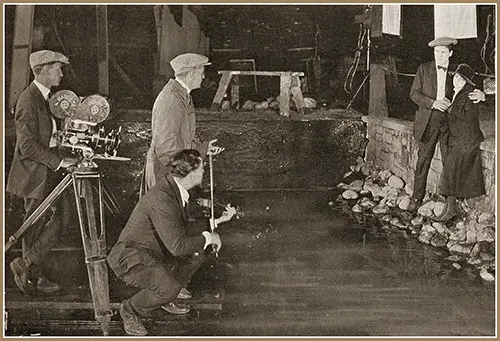

Griffith and Bitzer "Shooting" a Scene. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c962705e9

You remember, during the spring of 1917, the dire reports from the battlefront. The Premier, summoning the gifted men of Britain, is reported to have consulted with them about the best and quickest way to stiffen the nation's morale.

Barrie, Wells, Shaw, Bennett, Galsworthy, and Chesterton came to that meeting. How were they to open the eyes of the world to what was taking place on that blood-red battle-line? How inspire America with the ardor for a just war? Should they pool their talents in the writing of a book? Or a play of mighty import?

I shall always be glad to remember that the cablegram dispatched to America was addressed to me. That conference judged that the most effective medium for England and the allied nations was a drama of humanity, photographed in the battle area. Like the Macedonians to Paul, they sent out the message, " Come over and help us."

The wires brought back word that I was in London at the Savoy Hotel.

On the day I had expected to sail for America, I went instead to No. 10 Downing Street to meet David Lloyd George, Premier of England. I was proud that I had been elected to record and dramatize the spectacular events that were then making history. Most of all, I was thrilled at this acknowledgment of the power of the moving picture to narrate, stimulate, and perpetuate.

Vision The Primal Function in Motion Pictures

Of one hundred impressions received by the mind, eighty-seven are conveyed through the eyes. The love of movement is instinctive in us. We like to see the world go by. And the world, his wife, and his children give universal pleasure when they act out their lives on the "vertical stage" of the screen.

A learned man tells us that when we look at a motion picture, we are doing the most uncomplicated thing man can do, so far, at least, as concerns, the intellectual reactions aroused by the presence of an outer world. The movie eye is primeval. The movies were born almost in the mud of the world's first seas. To attend the film is to be primitive.

Mr. Dana does not assume that all moving pictures are easy to look at. I am sure he agrees that many of them are very hard on the eyes and intelligence. Because the movie demands the use of little more than the most primitive of all man's faculties, it wins frightful popularity for its understanding and enjoyment.

Pictures were man's first means of transcribing thought. We find these primitive thoughts cut into the rock on the walls of cave dwellings and lofty cliffs. A Finn as quickly understands the image of a horse as a Turk. A picture is a universal symbol, and a picture that moves is a universal language. Moving pictures, someone suggests, "might have saved the situation when the Tower of Babel was built.

The cinema camera is the agent of Democracy. It levels barriers between races and classes.

Visual demonstration is the most impressive means of teaching.

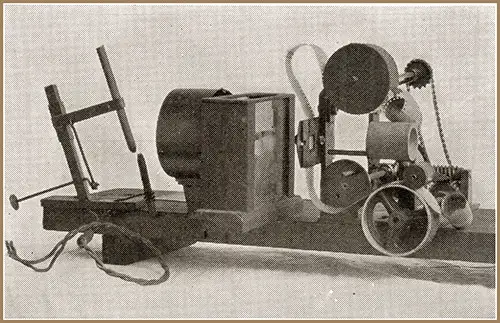

The "Grandfather of Movie Projectors." The Jenkins Invention Is Now in the National Museum, Washington. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID #

Propagandists know this. Educators say lessons learned with the moving picture are the least easily forgotten.

Motography unfolds the flower's petals and discovers the butterfly's secrets. It brings us face to face with significant events. It carries us to the peaks of mountains, the bottom of the sea, and the poles—literally to the ends of the earth.

The camera often tells the story of a popular novel better than the pen does. I think this is true of many pictures that have been made from famous books. Ibsen, Hugo, Barrie, and Mark Twain have risen to new triumphs on the screen. A director must know what is appropriate for the pantomime play and what is not.

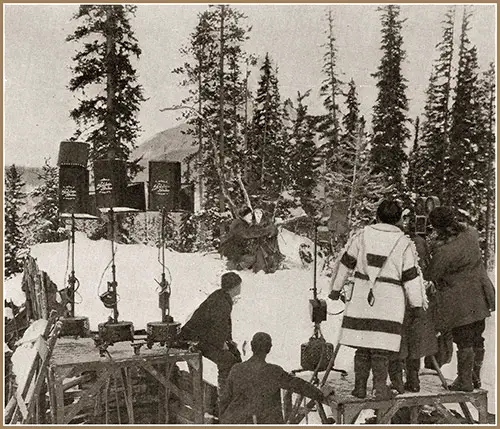

Filming the Sleigh-Ride Scene in "Way Down East." The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c962cfbac

In translating the theme of a play to the silver sheet, the moving picture director has several obvious advantages over the stage director. Scenes and backgrounds that can only be referred to in dialogue can be shown in the photographed play.

The "close-up" supplies the photodrama with a tool more effective for revealing character than any device on the theater stage. The "flashback" helps knit together the story's episodes and explains motivation.

Science and Invention - Who invented the movies?

Who invented the movies? Few of the thirteen million patrons who daily attend America's thirty thousand moving picture theaters realize how long and imposing is the gallery of cinema inventors. Many men of different nationalities have shared in the mechanical development of this most popular form of dramatics.

Lucretius, a Roman physicist, born about 96 B. C., first recorded the scientific principle of moving pictures or pictures that appear to move. Motion in images is an illusion.

The eye retains the impression of an object approximately one-sixteenth of a second after the thing passes on or disappears. You have seen a boy whirl a stone at the end of a string, and you recall seeing a continuous circle.

A Picture at White Heat. The Director and His Battery of Cameras in Action During the Making of a Big Scene in the Screen Version of Ibanez's "The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse." Courtesy Metro. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9648e5bf

When the boy swings the stone, the beholder's vision retains the reflection of the image a fraction of a second after each successive degree of revolution. Vision, in other words, persists.

The picture of one position blends into the next. When a strip of film is run through a camera and is thrown on a screen utilizing light, you get the effect of uninterrupted action. Look at the ribbon-like movie after it has been developed and printed, and you will observe a series of images.

Only by following carefully from one to the other can a change in pose be observed. A "moving picture" is a series of "still" photographs of changing poses, magnified approximately 35,000 times by a projection lantern.

The principle of persistence of vision was applied to blending successive positions of a moving object about a century ago in a crude experiment called a " Thaumatrope."

A forward step in moving picture invention was Plateau's Phenakistoscope. The Phenakistoscope utilized the principle of the intermittent shutter used today. A group of foreign inventors was engaged at this time in similar efforts.

The "Wheel of Life," invented in 1834, is still used by toy makers to amuse boys and girls. This was the first animated-picture machine that had a popular sale. Many others followed, some of them of serious intent.

The inventor of the Kinematoscope was a Philadelphian, Dr. Coleman Sellers. His patent application clarified that each image should be stationary from the moment it was in view.

It was vital to the invention's success that one picture's reflection should be timed to remain on the eye's retina until the next one came into view. Dr. Sellers was also the first to use the plating bath of glycerine, a predecessor of the now familiar dry-plate process.

Strings were stretched from the camera shutters across the track. When the horse came by, their hoofs caught the strings and exposed the plates by releasing the shutters. The experiment determined that the horse was clear of the ground at periodical moments.

Muybridge startled the world a few years later by photographing a dog's heart beating.

Strings were stretched from the camera shutters across the track. When the horse came by, their hoofs caught the strings and exposed the plates by releasing the shutters.

The experiment determined that the horse was entirely clear of the ground at periodical moments. A few years later, Muybridge startled the world by photographing a dog's heart beating.

The invention of the roll film was a development as necessary to the future of the industry as the invention of the needle-point eye was to Elias Howe's sewing machine.

About thirty years ago, an Englishman, W. Friese-Greene, demonstrated its use in a picture twenty feet long, showing the traffic at Hyde Park Corner, London.

You will smile at the idea of a moving picture that consumed a third of a minute in the "running." But, said Mr. Friese-Greene, (the cable brings news of his death as I write), "It was a triumph and a sensation, I assure you."

The flexible film used in a motion picture camera of standard type is the same size as the one introduced by Edison thirty years ago. The roll is one and three-eighths of an inch wide; a thousand feet make up a "reel."

Perforations gauge the film on the sides to catch the sprockets that guide the strip through the camera and projection machine. It takes thirteen or fourteen minutes to run off a reel.

Thomas Edison, the inventor of the celluloid film, first exhibited his Kinetoscope in 1893. Edison, the American, Lumiere, the Frenchman, Paul, the Englishman, all had a part in furnishing amusement to a world audience of picture patrons.

The First "Movie Show" - The Miracle of Modern Photography

In June 1894, an amateur inventor named Jenkins arrived at his hometown in Indiana on vacation from his job in the Treasury Department, Washington.

A mysterious box had preceded him. When it was unpacked, the neighbors were called in to see what was to be known in history as "the first movie show," the first exhibition of motion pictures projected on a screen.

When Jenkins exhibited his motion pictures at an Atlanta exposition, people refused to pay the admission fee in advance. The exhibitor had to let his patrons go in and see the miracle before he could convince them that it was not a swindle.

A combination of the Edison and Jenkins-Armat interests resulted in the creation of the Vitascope, a radical improvement over the picture machines into which one looked through an eye-piece, or "peep-hole."

Nature No Obstacle. When the Play Calls for "Snow-stuff," the Motion Picture Producer Often Goes Miles To Get It and, as in This Case, Augments the Natural Light With Our Lights. Courtesy Goldwyn. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c96d92205

Walking the Chalk Line. This Director Takes No Chances With the Success of His Wedding Scene. He Sits on the Traveling Camera Platform Trailing a Weighted Line To Keep the Actors in the Middle of the Imaginary Church Aisle. Courtesy Goldwyn. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID #

Even those of us that are not very old can remember the names of some of the first motion picture stories—" The Buffalo Horse Market," "The Black Diamond Express," " Niagara Falls," "The Pillow Fight," and "Feeding the Pigeons."

The first "long" film was " The Great Train Robbery." Great was the public's astonishment in the viewing of it. It consumed 1800 feet of film and cost four hundred dollars to produce.

A dozen years ago, "picture acts" became a part of the program of popular vaudeville houses. At the Eden Musee in New York, Edison's "topicals" were shown. It was about that time that I began to make film plays at the old Biograph Studio on Fourteenth Street, New York.

Staging an Automobile Wreck. Behind the Screen With the Director and Cameraman. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c970bd0c0

I have made five hundred pictures in the thirteen years that have passed. I created some of my early photo tales under strenuous conditions. When I proposed making a two-reel drama, my backers declared that people would never sit through such a long picture.

We compromised by cutting the first two-reel picture in half. We named the first part "His Faith" and the second "His Faith Fulfilled." The public liked it and asked for more. Not long afterward, I made a five-reel picture, "The Escape," and then the first ten-reel drama, "The Birth of a Nation."

Most screenplays are now five reels (5,000 feet) long. A few "master productions" run to ten reels. Weeks of research, experiment, and rehearsal; the talent and patient industry of authors, continuity writers, directors, actors, artisans, artists, decorators, costumers, lighting experts, "location scouts," cameramen, and their assistants, contribute to the finished picture.

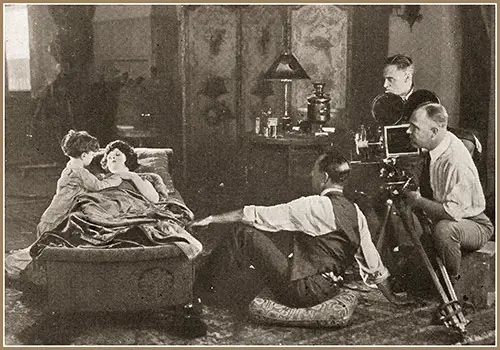

Making an Emotional Close-Up. The Director Rehearses the Actress Until Her Performance Satisfies Him; Lights Are Called For, and the Camera Begins To Grind. She Must Go Through the Scene Amid a Running Fire of Orders From the Director. Courtesy Realart. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c97405f97

The Motion Picture Editing Process

When the film has gone through a series of laboratory processes, it returns to the dramatic director to be "cut," assembled with the sequence of time and climactic effect.

The success of a picture may depend upon the skill of a director in cutting. The director spends days in a projection room with a man or woman cutter at his side. The film is clipped and joined according to his instructions.

A Battery of Cameras. An Array of a Dozen or More Cameras Is Assembled To Make the Scenes of a Big Picture. Courtesy Metro. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c97bf7013

The highest standards of picture production now demand backgrounds, lighting, and photography as experts as the acting and direction. Every day is a sunny day where the Sun burns.

With the help of powerful lights, the indoor studio can be flooded with rays stronger than sunlight and more easily regulated. The rain never interferes with the making of scenes under a studio roof.

Exteriors are often built in the studio with better results than if made on the " lot " or " on location." my studio at Orienta Point, Long Island Sound, has no outdoor stage. Even in California, directors are forsaking the sunlit stage for the studio equipped with the latest " Kliegs " and "Cooper-Hewitts."

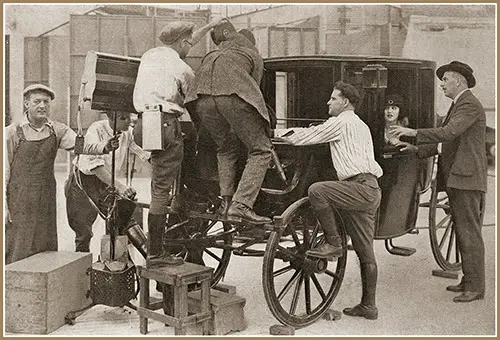

They Were Filming Action in a Cab Inside a Studio. The Author Can Call for a Few Settings the Producer Cannot Provide. This Shows an Episode Pictured in a Photoplay From the Popular Novel "In the Bishop's Carriage." Courtesy RealArt. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c97c34159

The world moves fast; nothing has moved so fast as the moving pictures. They have advanced from an experiment to a tremendous industry in a decade and a half. Half a billion dollars is spent in the United States every year on making photodramas, comedies, educational films, animated cartoons, and news reels.

Besides the investment in production, there is the cost of experiments in the machine work. We are still improving the super-camera that takes the motion picture snapshots, trying to increase the lens's speed, shorten the focus, and perfect that critical piece of mechanism, the tripod.

The superiority of modern motion picture photography is due entirely to the short focus of the lens, which permits actors to move about the scene at will without blurring the outlines.

Today, the director has many novel devices at his command—the " fade-in " and "fade-out," the "flashback," the "close-up," "mist photography," the vignette, double exposure, the multiple prints.

Had I had the business discernment to patent certain of these effects, I would have realized more money than I could have earned in a hundred years by making motion pictures.

When I first photographed players at close range, my management and patrons decried a method that showed only the face of the story characters. Today, nearly all directors employ the close-up to bring a picture audience to an intimate acquaintance with an actor's emotions.

When, during the filming of "Birth of a Nation," I proposed making a "long shot" of a valley filled with soldiers, I met flat opposition from my staff. Until then, a screen army had numbered half a dozen uniformed men. The rest of the forces were left to the imagination.

Working Up "Atmosphere." Music Has Been Found Valuable in Making Motion Pictures. Here the Director Is Explaining the Scene He Is About to Photograph. At the Same Time, a Violinist Supports His Words With Music That Puts the Actors Into the Scene's Spirit. Courtesy Paramount. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9831b580

I adopted the "flashback" to build suspense, which had been a missing quantity in picture dramas. Instead of showing a continuous view of a girl floating downstream in a barrel, I cut into the film by flashing back to incidents that contributed to the scene and explaining them. The photoplay of the present would be counted an arid thing without the diversion supplied by these now familiar aids.

Within late years a daylight screen has been perfected. The combination of the voice and the motion picture has long been an ideal of Mr. Edison and other inventors. I adapted parts of "Dream Street" to the use of improved "talking pictures."

Color photography offers fascinating possibilities. Using recently patented processes, subdued natural colors are accurately registered without the "jumping" that formerly marred the beauty of the tinted picture. I believe there are great opportunities in the field of phonograph-projector.

There is a considerable margin for improvement in distributing and exhibiting pictures. I hope the time will come when patrons will not be allowed to enter a theater except at the beginning of a photoplay that the casual hospitality of the picture theater of today will not exist.

The public will then regard the performance with respect they now show for stage plays. This problem phase engages us all—how to translate a manufacturing industry into an art and meet the ideals of cultivated audiences.

For, paraphrasing Walt Whitman, "To have great motion pictures, we must have good audiences, too."

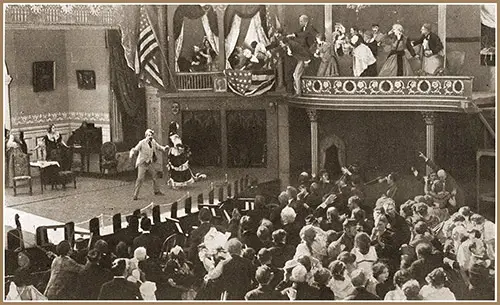

History Repeats Itself on the Silver Screen—Assassination of President Lincoln, "Birth of a Nation." The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID #

In And About The Movie Studio

Some Might Call This Picture "In Arcady," but That Would Not Explain Why a Famous Novelist Is Shaking Hands With a Pleasant-Faced Man in a Checked Suit. Sir Gilbert Parker Congratulates the Producer of His Latest Film Story on Its Completion. The Cast Is Also Happy. Weeks of Hard Work Have Just Ended Under the Blossoming Boughs of California. Courtesy Paramount. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9874e080

The Author And Motion Pictures

By Rt. Hon. Sir Gilbert Parker

I have never been converted to the approval of motion pictures. I believed in them from the first, and further acquaintance with the art—I use this word deliberately—has only deepened my faith.

I know how bad so many of the pictures shown on the screen are, but the art is very young and progress made since the days of the "nickelodeons" is immense.

Not alone the manufacturers of motion pictures but also the public. Public taste has developed, and with its development has come a demand for better and better pictures. To what is the progress due?

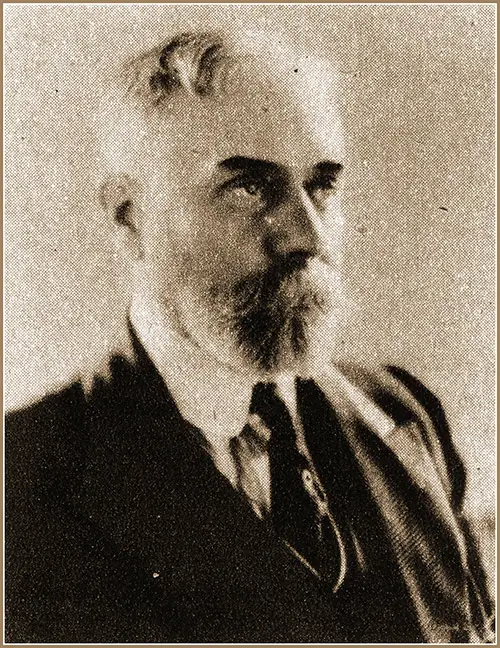

Sir Gilbert Parker. Author of "Pierre and His People," "Seats of the Mighty," "The Right of Way," and Many Other Successful Books and Photoplays. Courtesy Paramount. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c98ac333d

At one time, it seemed that the semi-nude and the slightly salacious were needed to draw the public, but that day was fast going. On the whole, the public taste is right. It may flirt with the suggestive on the stage, but in the end, it is true to the best instincts of life. Consider how law and order are kept in big cities.

It is not alone the administration and the police. It is the will of the community. The community's choice is in vast preponderance for the good, stable, and correct things. Else, social life would be chaos, and disorder would reign everywhere.

So with the films. At first, the semi-nude and tights and suggestive scenes were attractive, but the success of the movie free from all that is proof of the soundness of public taste.

If you take the most successful films, one will find that they have naught of the salacious and the sensual, from "The Birth of a Nation" and "The Miracle Man." Many of the most successful, like "The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse," end unhappily.

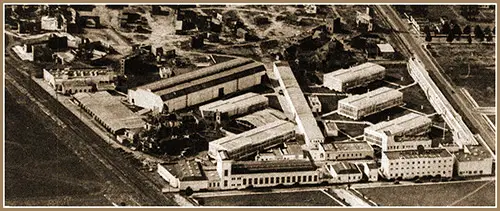

A California Picture Town. An Airplane View of Studios, Dressing-Rooms, and Outdoor Sets. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c98de857e

Let me take one case from my own experience. "The Right of Way," a story that ends unhappily—in the conventional sense—was twice produced by the Metro organization.

The first production was not a success with Faversham in it—not from any fault of Faversham—and the Metro produced it again. Without my knowledge, they made two endings, that of the book and also a happy ending, and submitted them both to the trade.

The trade decided on the book's ending, one of the most successful motion pictures of the last year, as the box-office receipts show. One can trust public taste. Take "Madame X"—is that a happy story? Does it end happily? No, yet it is abundantly prosperous.

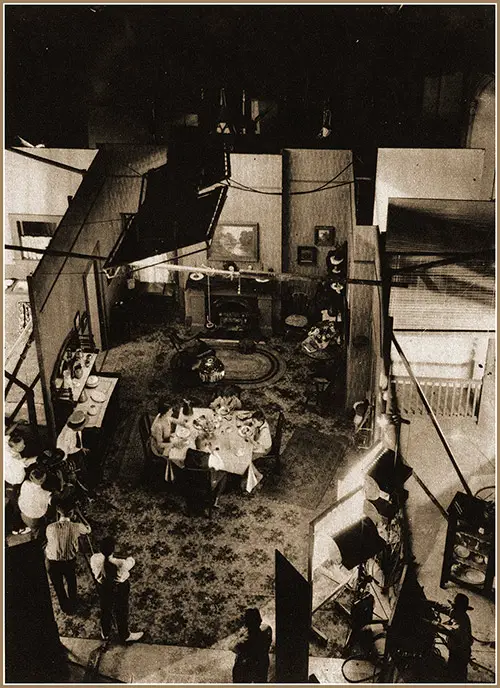

A Scene in the Making. A Remarkably Graphic Picture of a Studio "All Set" for Filming. The Scene Is From One of Booth Tarkington's "Edgar" Comedies. It Shows Three Separate Rooms and Effectively Demonstrates the Fact That "Lights' and "Camera" Are as Important as "Action" in the Motion-picture Making. Courtesy Goldwyn. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c99106d40

I have from first wondered why film producers did not make motion pictures of historical novels, where there were no royalties to authors to pay, and I was told the public would not patronize them. I replied that the people did not have an excellent chance to judge, for the historical motion pictures had not yet a fair chance.

Someone told me to see the fate of "Joan, the Woman." Well, I saw "Joan the Woman" and a fantastic film it was. Still, its failure, or rather partial success, was due to other causes than its historical nature, as the world knows.

At last, the success of "The Mark of Zorro." "Passion" and "Deception" have turned the views of the trade, and "The Three Musketeers" is produced with the help of Edward Knoblock, an authority on the history and costumes, and customs of that period.

I am glad the film producers have been convinced. The trade will produce historical romances again, and many will fail because wearing effective historical costumes without self-consciousness requires the training that Shakespearian dramas give. There are not very many in the film world that has had that training. Still, I hope the inevitable failures will not turn them antagonistic once more.

I have always believed that every influential author will want to write for the film stage in good time, and that time is at hand. To say naught of eminent authors in the United States, in England Pinero, Arnold Bennett, Robert Hichens, Edward Knoblock, Somerset Maugham, Elinor Glyn, and .even Kipling, are writing for the screen, and my prophecy is fast coming true.

Henry Arthur Jones is now in America making scenarios for Paramount; Sir James Barrie, whose "Sentimental Tommie" and "Admirable Crichton" have already found their way to the screen, is to assist in the American production of "Peter Pan."

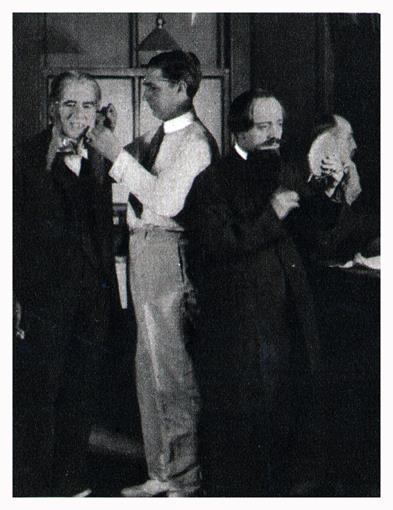

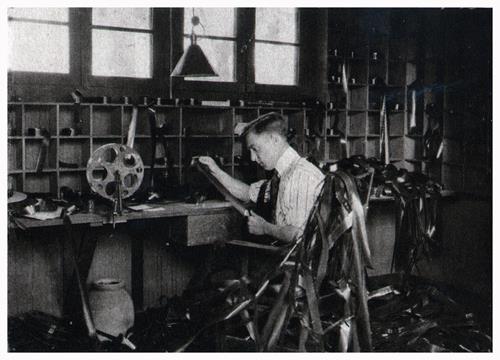

The Make-up Man. Indoor Make-up Techniques Varies Significantly From the Stage Drama Because of the Effect of the Studio Lights. From "Behind the Motion Picture Screen," by A. C. Lescerbount. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c994fb3b1

Film writing is not an easy art to learn, but authors must understand it, or their books will be butchered as they have been in the past, and no one will say them nay.

One of the worst features of the film business today is the titling. Few films have good titles, yet a title may be as important as a scene, even more so.

Titling is terrible in one way, for it distracts the attention from the picture. Still, it can never be abandoned, I fear. However, there is a film on now, James Whitcomb Riley's "The Old Swimmin' Hole," with no titles. Still, this story is extremely primitive, and titles are not needed.

Finally, let me say I do not think the film will destroy the taste for the stage. It will make new lovers of the stage as the music hall has done. Though for the present, the theater galleries throughout this country have been badly affected, I believe it is because people can see a film from the gallery at one-third or one-half the cost of a gallery seat in a theater that the theaters have been injured in that portion of the house.

The film goes where there never was a theater and helps create dramatic taste. How many churches are there throughout the country where movies are shown?

About a stone's throw from where I write this article is a church where a film was shown last Sunday night called "Our Country As It Is." The time will come when every school and every church will have a piece of moving picture equipment.

Governments distribute films to schools and organizations. Universities and schools use the screen picture to teach history, literature, geography, and science. Explorers are bringing back graphic reports recorded in celluloid. Thanks to the motion picture, the world is better taught and informed.

When a Wedding Scene Is Made. A Minister Is Frequently Called In To Consult With the Director. One Is Here Shown Instructing a Bride and Her Attendants in Ceremonial Details. Courtesy Realart. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c99a9d22d

A Baby "Extra." Entertained by a Film Hero While Her Play Mother Discusses the Script With the Anxious Director. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c99fe2a47

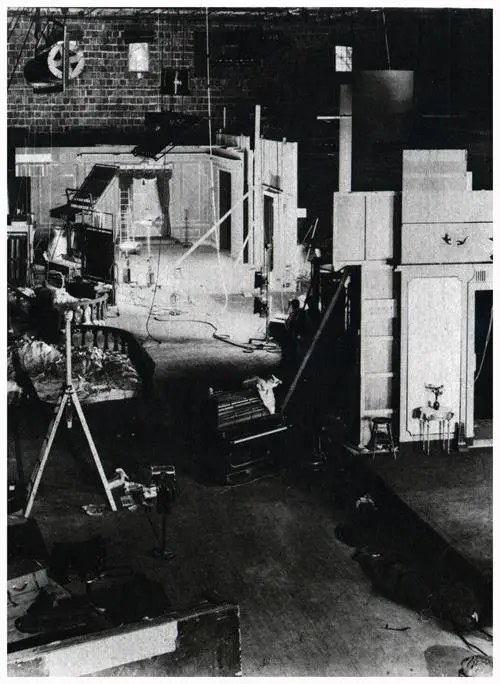

A Movie Workshop. On the Floor Are Several Indoor Sets and an Exterior. Above the Front Yard of an Old-fashion City House Is a Cylindrical Machine That Supplies Snow Storms on Order. Courtesy Griffith. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9a14580f

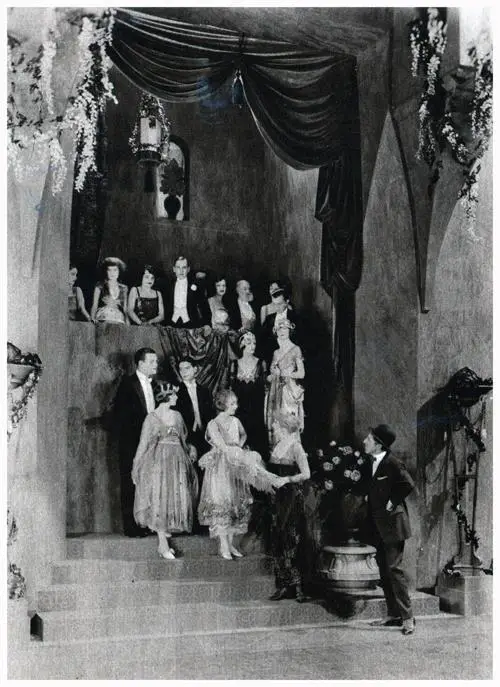

A Ballroom Scene in "Way Down East." D. W. Griffith Directing. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9a3e4d55

In The Land of Make Believe - The Miracle of Modern Photography

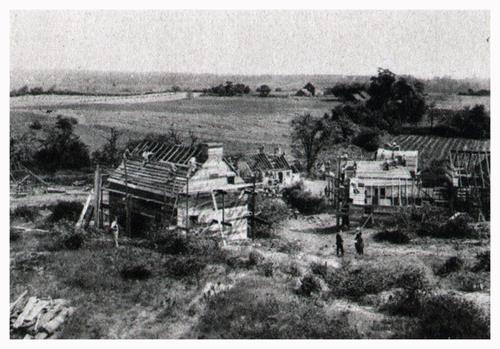

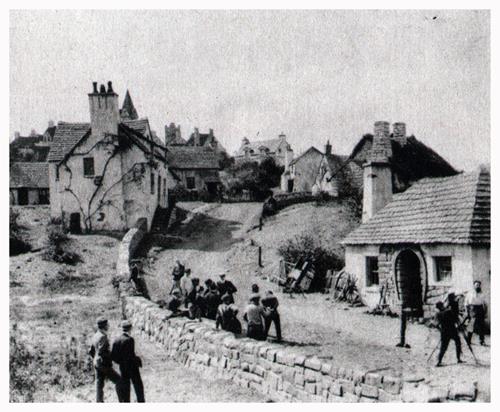

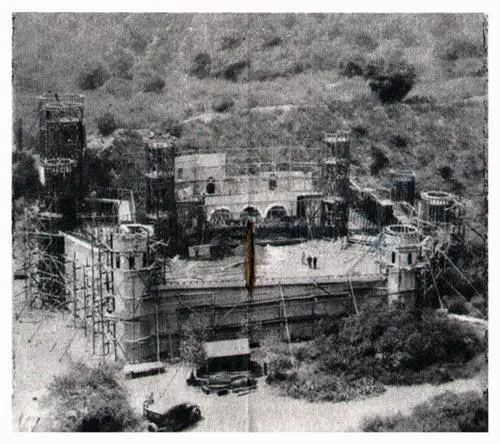

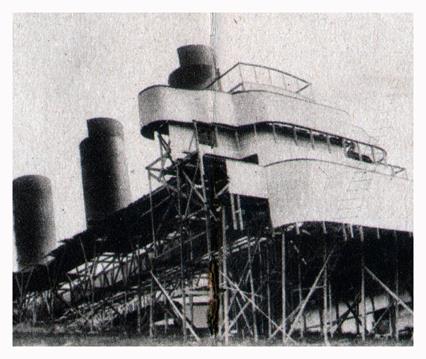

Landscapes are changed, and historic buildings are reconstructed. Scotch Thrums comes to life on the meadows of Long Island; King Arthur's towers rise among the brown hills of California. Gigantic walls make a towering background for a Babylonian pageant.

Barrie's Village of Thrums Was Recreated Near Elmhurst, Long Island, for the Film Play Based on the Scotch Author's Books. "Sentimental Tommy" Was Recently Released. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9a4db53c

The Director's Parents, Who Had Lived Near Kirriemuir (The Original of Thrums), Pronounced This a Perfect Facsimile of the Illustrious Village Across the Sea. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9a692680

King Arthur's Castle at Camelot and the Halls of the Round Table Knights Were Reproduced in the Film Version of Mark Twain's "Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur's Court." The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9a873efa

In "Behind the Motion Picture Screen," a Picture Play That Featured a Realistically Looking Ship in the Haunting Tragedy of the Lusitania, the Upper Part of the Fated Ship Was Made With Lath and Plaster. Scientific American Pub. Co. The Mentor, July 1921. | GGA Image ID # 1c9ab0f3c5

This Model City Is Just Half as High as an Electric Fan. (Look Over to the Right and See the Fan.) On the Screen, the Buildings Were Made To Appear Full Size. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9acaaa10

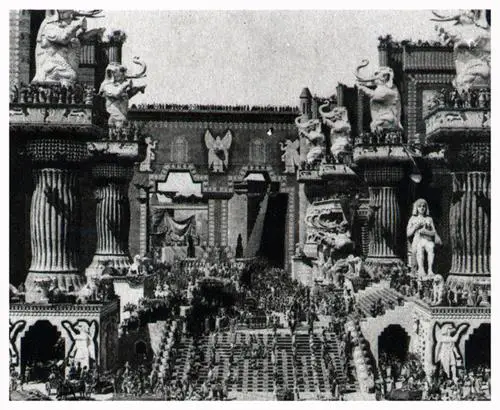

This Gorgeous "Set," Erected for the Griffith Spectacle, "Intolerance," Established New Standards in Motion Picture Architecture. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9aeedb12

The Scenic Background - Motion Pictures

By HUGO DAWN, Artist and Director

DURING the past few years, motion picture producers have seriously considered the subject of sets and settings. They have employed men skilled in architecture, in effects of light and shade, in the disposition of masses of color, and suitability.

The producer now realizes the value of color—the simplified background—the balance of wall and window space. Today the actor's work is less challenging to follow. His skill is not confused by screaming designs by inappropriate and misapplied ornateness.

Thousands of Drawings. In the Illustration, We See the Overhead Camera Trained on the Frame That Holds Sheets of Drawings Arranged in Scenes. The Pressure of a Foot Pedal Exposes the Lens. This Operation Is Repeated Until All the Sheets Are Photographed, and the Film Is Ready for the Projector. Courtesy Bray. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9b25c69e

Cartoonists, animators, and camera boys labor for 30 days to produce a film that can be shown in 10 minutes. Thousands of drawings must be made for an animated cartoon of average length.

Early motion pictures represented what the man dressed on the set considered a refined luxury and what the dramatic director was willing to accept as background.

The average director still has a mighty fancy for flamboyant walls and furnishings; some have been converted from this grotesque decoration.

We have progressed but still have before us a lengthy course. The development of beauty travels at a snail's pace.

The public has grown to understand the composition. It knows better sets. It supports better stories. The producer is learning that good backgrounds and light affect an excellent story.

The public may not be able to analyze the why and wherefore. Still, the old form of decoration is peeling from the canvas and disintegrating.

A setting is of little service to the drama if the drama does not dominate. The action is paramount but can be so only if the background is not obtrusive.

Perfect sets have never made a drama. The audience follows the story. Settings can explain the story. Settings are dramatic rhetoric.

They should be indicative of breeding. When they are overlooked, they are poorly thought out. When settings receive uncommon notice, the drama is defective.

Settings are the photographer's hope. A good setting helps reduce the number of subtitles—the aim of all idealistic directors. A good background often elevates the achievement of the player. A lousy setting has never elevated anything. A good set can be spoiled by bad lighting — and an awful set can be saved by good lighting.

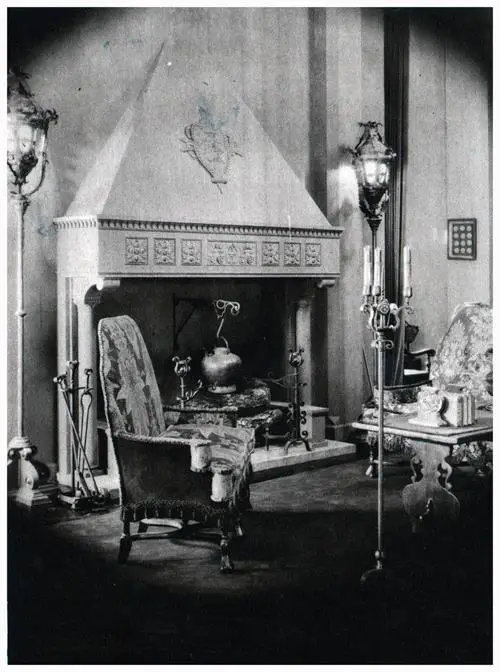

An Antique Italian Room Reproduced by an Artist-Director Who Believes That Truth Is Beauty and Follows His Creed. Courtesy Goldwyn. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9b572764

Lighting is motion picture composition. "Shaft lighting" gives a semblance of parallax (an apparent displacement of L an object due to a 17" observer's position). A motion picture has no parallax. The noticeable shifting of an object, or the ability to see around a thing, is caused by double sight or the vision of two eyes.

A lens represents one eye. It may be the right or the left. The depth of a motion picture is infinite. Its width is finite—it has limits. Therefore it is essential in sets to get depth, not width. An audience knows two reactions concerning a set—it is pleasing or not.

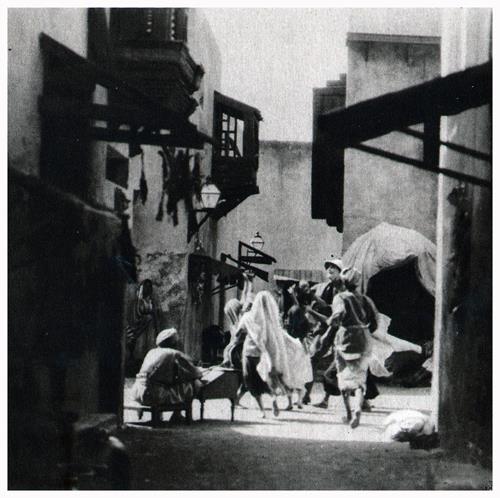

Kipling's Stories Have Reached the Screen. The Sets for "Without Benefit of Clergy," the First of Kipling's Short Story Classics To Be Filmed, Were Designed According to the Author's Suggestions. Courtesy Pathe. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9b635fb8

A man does not readily believe in a thing he does not see or know. There is no greater mission for the art director than to concoct a picture that bears the semblance of composite truth.

Motion pictures must tell the truth to be convincing. Beauty affects us by association. Sometimes when the association has been forgotten, the memory of beauty remains.

The impression of great beauty is an expurgated memory of things we have enjoyed. True art is simple—simple beauty. Most motion picture backgrounds are not simple. The average picture suffers from a superabundance of complications, which applies to both sets and acting.

A Studio Carpenter Shop Is Equipped To Build Anything From Chariots to Churches. Courtesy Lasky. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9b7d39e7

When an audience realizes that the background is artificial—it has been constructed for the play, the production suffers. As long as a set suggests the studio, it fails in its mission.

The prime mission of the screen is to entertain. The most astute latter-day producers recognize the commercial worth of taste and judgment, an understanding of proportions, rhythm, and tempo, and the more exemplary values of drama, good acting, design, and composition.

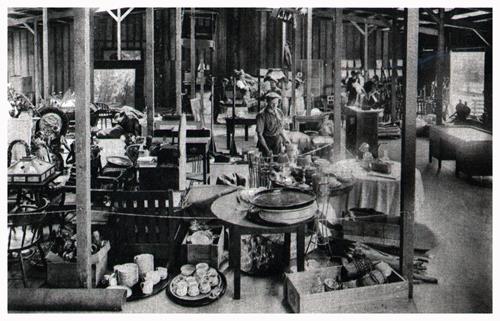

A Studio Property Room, a Fascinating Department in Moving Picture Establishments. From "Behind the Motion Picture Screen." Scientific American Pub, Co. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9b8c1d52

It is vital to make beauty clear, and more essential to make it affect the imagination. It is this latter development that artists and directors look for. Still, we cannot venture too far on this ground until we know that the public, the ultimate arbiter of our destinies, gives us unstinted approval and applause.

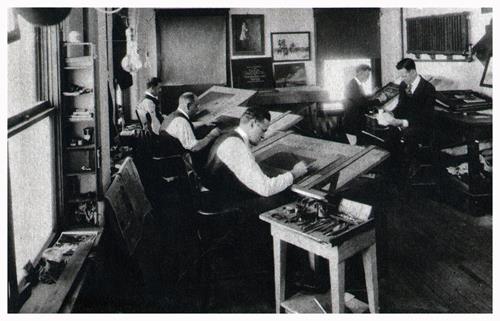

Designing and Printing Titles. This Work Engages the Talent of Experienced Artists. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9bebf4a1

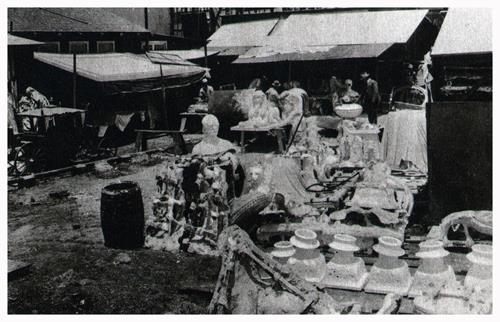

A Studio Within a Studio. Trained Sculptors and Cast Makers Make to Order Whatever the Art Director Requires. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9c33e0de

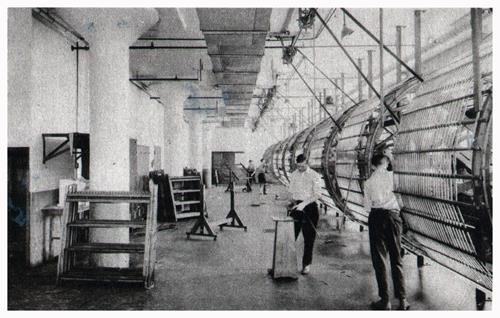

Drying the Negative. The Film Is Wound on Revolving Drums When It Comes From the Developing Room. Courtesy Educational Films. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9c75c592

In the Cutting Room, Miles of Printed Celluloid Ribbons Are Handled in Assembling a Complete Picture. Sometimes a "Cutter" Becomes So Expert in Arranging Scenes That His Director Leaves Most of the Job to Him. From "Behind the Motion Picture Screen." Scientific American Pub. Co. The Mentor, July 1921. | GGA Image ID # 1c9ce78a7b

Scenery That Acts - Motion Pictures Historical Scenes

Scenery That Acts. The Scenes Made for "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" Are the Latest Word in Moving Picture Background. They Picture the Hallucination of an Unbalanced Mind. Courtesy Goldwyn. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9cec569e

An inmate tells the story of an asylum drama who believes the asylum's leading physician to be the reincarnation of an evil Dr. Caligari, who lived in the twelfth century and traveled about the country with a somnambulist who exhibited at fairs.

According to the inmate's story, the doctor rejoiced in making the somnambulist commit crimes, and the inmate believes himself to be the hero who will convict the evil Caligari. The scenes form a series of remarkable "futurist" compositions.

Streets curve crazily, lantern posts lean in wide angles over stone walls; and doors and halls achieve the uncanny spirit of the story by being mere oblique lines or a disconnected series of curves.

Long triangles of splotched color stretch upward to form a striped, hollow pyramid; draperies hanging in a festoon, like a huge blanket, sag with the weighted impressions of falling skies, imminent catastrophe, or doom. The weird background has been called "scenery that acts."

Dramatists and the Photoplay

Motion Pictures: The Miracle of Modern Photography

By Henry Arthur Jones

Henry Arthur Jones, Author of "The Silver King," "Saints and Sinners," "Middleman," "Mrs. Dane's Defense," and Others. Courtesy Paramount. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9cf0bf20

THE dramatist wins enduring renown for his dialogue and his dialogue alone. To write a successful play, he must, of course, have other gifts and acquirements. He must call in the scene-painter, the upholsterer, the costumer, the electrician, and other adjutants to help him to express himself.

But his dialogue alone has permanent value;' all the rest of its trappings are perishable. The difference between "Macbeth" or "Hamlet" and a stock melodrama is that "Macbeth" and "Hamlet" can be read and studied as literature.

They are literature. That is why they have held their place in our theater for three hundred years. That is also why they often fail on our modern stage.

They demand serious thought and feeling from an audience. They ask for an examination and offer emotional and intellectual enjoyment on these grounds. The film cannot afford the quality and kind of pleasure spoken drama can give—the joy of literature.

The actor gets his finest and worthiest effects mainly by the voice. Again, the voice has always been the chief gift of the actor, his chief means of swaying his audience and stirring their emotions. What the dramatist has written falls dead upon the stage unless the actor vitalizes it.

It is clear that, as the film play forbids the dramatist to use his chief and highest means of expression, it also prohibits the actor from using his chief and highest means of expression.

What balancing advantages and compensations can the film offer the actor and the dramatist? To the film actor and actress, it offers universal, though not immortal, fame by displaying their pictures in every city of the civilized world, perhaps in five hundred theaters on the same night. It further offers to star performers an enormous salary.

What are the advantages offered by the dramatist? In the volume, variety, and impetus of its action—that is, in the very essence of drama—in its swift, vivid, multiple transformations, its startling command of contrasts, its power of concentration on valuable minutiae, its capacity for insinuation and flashing suggestion—in all these theatrical qualities the film play offers the dramatist an infinitude of opportunity compared with the spoken drama.

Aristotle compared the limitations of the drama with the expanses of the epic. But, compared with the film, even the epic, the novel becomes a tedious chronicler of events.

The film is a bungler at comedy, except for the rude and boisterous kind which Thalia reproves. But the film invites and welcomes Romance and Imagination and opens a large field for their exploits. Now, from Shakespeare downwards, imagination is largely shut out from our modern stage, with its pert vulgarity and dictionary of slang.

Tongue-tied already and almost banished from the spoken drama, imagination may perhaps find a home in the film theater. She will be deprived of speech, but how rarely she is allowed to open her lips upon the regular stage!

Let imagination find utterance in the vast pictorial resources and devices of the film theater, throw her magic begins amongst its fascinating lights and shadows, and employ the quick vibrations and successions of the screen to tell more powerful stories of human life than are being told today upon the stage of the spoken drama.

Fiction Writers and Motion Pictures Scenarios

By Rupert Hughes

Rupert Hughes, Dramatist, Novelist, and Short Story Writer. Courtesy Goldwyn. The Mentor, July 1921. GGA Image ID # 1c9d2e8d3c

"PICTURES" have had good stories for a long time. When images were first thrown upon a screen, it was beautiful to see a man walk, stretch out his arm, or smile. What have pictures failed to do in advance with their audiences?

Later it was even more wonderful to see a train wrecked, a house burned, or a maiden rescued. But now, all those things are no longer novelties.

The smallest boy sees nothing remarkable in the mere action of pictures; he no longer thrills over the wreckage of locomotives, for he knows every little trick of the trade. He can tell you the very instant that a dummy is substituted for the actor in an accident.

The mere mechanics of the movies have lost their thrill because their novelty is gone. The one thing to do, then, is to sound to the audience; the only way to reach it is with sincerity.

That is the crying need for pictures now. They must appeal to the audience as real. Their grief must be sincere, their humor genuine. Depict real life for people, as the best play and novel does, and the photoplay will hold its own.

As a rule, storytellers know their business; that is why they are successful. And yet it is a fact that film companies pay thousands of dollars for some stories by a well-known author. The author could not recognize his story when it went through the scenario editor's hands.

Nothing is left but the title and the author's name. The main reason is that it is a scenario editor's religion that a storyteller can never write anything wholly suited to the screen. The scenario writer makes no effort to understand the theme of the original story but thrusts it through conventional actions.

For this, authors have stormed against motion pictures, and you can't blame them. The picture producers bought their stories, then threw away the plots, and, substituting ideas of their own, merely kept the titles, sometimes, and a few of the characters.

Some have not blamed the motion pictures so severely for this. I realized that they were going through a phase in their evolution. The same conditions prevailed at one time on the stage and in the publishing business. The author got little credit, and his work was distorted to suit the fancy of producers and publishers.

Some of us have agreements whereby not a word of our writings is to be changed. We work in somewhat the same way with the picture producers. We work with the "continuity writer," the casting director, the director, and the film editor. And we help select the casts and attend rehearsals of our plays.

Suppose the moving pictures are to hold the people. The person who shapes the mold should know his audience, be conscious of his audience, and know the precise method of wringing tears or laughs from them. And if an author's works are good enough to purchase, they deserve to be presented with the background of the theme that the author evolved. In that case, one must introduce novelty, and the place to do this is in the scenario end of the business.

We must strike at the audience's hearts and bring sincerity into pictures—then they will maintain their place as one of the arts.

The Author And The Film

By REX BEACH

Rex Beach, Author of "The Spoilers," "The Silver Horde," "The Barrier," "The Iron Trail," and others. Courtesy Goldwyn. The Mentor, July 1921. | GGA Image ID #

THE public is beginning to pay more attention to motion pictures and treat them seriously. A new attitude developing all over the country is very significant, especially concerning well-known authors in pictures.

Producers have been tricked into activity by new enterprises that have engaged the services of established writers—writers of books that make picture material of broad appeal and range of interest—writers whose names frequently appear in the best American and English periodicals.

These authors are writing on themes vital to the people—on things of present and immediate interest. Their picture plays to claim the attention won by the publication of their novels, first in magazines and then in best-selling books.

A few years ago, the gap between the American author and the photoplay was so broad that combining the two in the producing field seemed a distant vision. Within the last year, the author's name as a valuable asset to the motion picture has become as great as that of the actor-star.

Changes occur with lightning rapidity in the photoplay world. Still, the causes at the basis of this change are too fundamental to be attributed merely to the passing whim of the producer.

The public is, after all, the dictator of films. The public has learned, or rather, the public has been taught, that the author is just as crucial to the photo-play as a versatile star, lavish settings, and exquisite photography.

A few years ago, neither the author nor the producer realized their potential value to each other. As its future seemed, the motion picture was still in the experimental stage.

The author, in most cases, was unwilling to acknowledge that the newly popular medium was worthy of attention. On the other hand, the photoplay suffered from the absence of the guiding hand of the experienced fabricator of plots. It was in danger of becoming merely the agency for exploiting the personal screen success.

The rapidity with which both factors have acknowledged their need for each other attests to the prophecy that literature will be expressed through the screen and the printed page in the future.

Specific stories, of course, are not fitted for photoplay reproduction because they depend more upon psychological motives for their development.

The direct cooperation of author and producer—joins the trained hand of the author to that of the director on the throttle at the producing end. It results in coordinating all the production details by the man who created the plot, the characters, and the setting.

There is something to be said for the author who disdained the photoplay heretofore, who was forced to witness the mutilation of his story into an unrecognizable caricature.

Each side has now made concessions. Each has noted with approval the growing demand for a good story, a well-thought-out plot, and characters drawn from life rather than from the stilted lay figures of the studio. Each realizes the indispensability of the other.

The author is now contesting with the star for supremacy. His laurels, the many photoplays created from well-known novels in recent months, prove his value to the newest and most popular art.

The Camera As A Reporter

By HERBERT E. HANCOCK

Director-General of News Film

TWO hundred years ago, there were three estates, the Clergy, the Nobility, and the rest of us. Then Edmund Burke, the great British statesman, found a Fourth in the Press Gallery of the House of Commons. If he were alive today, he would create a Fifth Estate and designate screen reporters as its members.

Publishers' Photo Service

FILMING A FLIGHT. The Mentor, July 1921. | GGA Image ID #

The worn-out saying, absolutely incorrect that The Motion Picture industry is in its infancy can be applied with more truth to the News Reel, which, however, is rapidly approaching a state of adolescence.

Today's wrong-doer dreads the camera's searching lens even more than the vitriolic pencil point of the reporter, while the hero and the publicity seeker vigorously dust off the "Welcome" on the door-mat at the approach of both.

The News Reel camera operators of today are few in number. There are not more than two thousand in the United States and Canada. It takes a man of a unique type to become enough of a cameraman to make a good living. A News Reel producer employs very few camera operators on salary.

Only in the big cities does he have to keep them on salary. The others are free-lance operators known to the craft as "field men." These men get paid for the film that the News Reel editor accepts. If it is rejected, the film is a dead loss to them.

There is no harder line of work than that of a News Reel cameraman. Unlike the reporter who carries a few scraps of paper and a pencil, the cameraman lugs an outfit weighing anywhere from 30 to 60 pounds. In many cases, it has to be set up, threaded and focused with lightning speed.

He must understand photography down to the 'nth degree. He must be somewhat of a director. He must be able to read the mind of his editor to a certain extent to get the most exciting news angles possible.

A man who has earned the degree "First-Class" is not only a good photographer but a man through. And he must be essentially a diplomat. Also, when the occasion arises, he must take his life into his hands.

At first thought, it appears incredible that so many strive for this position in life, with such a hard road ahead to travel. The reason is that NewsReel's work demands the creation of something. A man is put upon his mettle, and a real man likes that. Perhaps the most alluring part of it all, however, is the power that his work gives him.

The news camera is a powerful weapon for either right or wrong. Thousands of eyes see the newspaper article; millions see the current events picture on the screen. Whereas a newspaper lives for not more than forty-eight hours, a News Reel's life is about ninety days.

Frequently, as in my case, the director of a screen weekly is an ex-newspaper man. He assigns his local staff to cover events just as an editor does. He must know, above all, what kind of news will appeal to the multitude.

I prophesy that the News Reel will dominate the field as the public megaphone within a few years. As soon as its power is understood, it will be recognized as the most potent representative of the Motion Picture industry. The day will come when it will speak with the nation's voice.

Making The Motion Picture Program de Luxe

By S. L. ROTHAFEL

Creator of the Motion Picture Program de Luxe

Not so many years ago, fifteen to be exact, I was running a little movie show behind a barroom in a mining town in Pennsylvania. It was a one-person show. I painted my displays, ran the projection machine, and sometimes walked miles to the nearest exchange to get the pictures.

Even then, I had confidence in the entertainment value of the motion picture—as much, I think, as I have in my present capacity as director of productions at the world's largest theater—not only the largest one consecrated to the Motion Picture muse but the largest devoted to any theatrical enterprise.

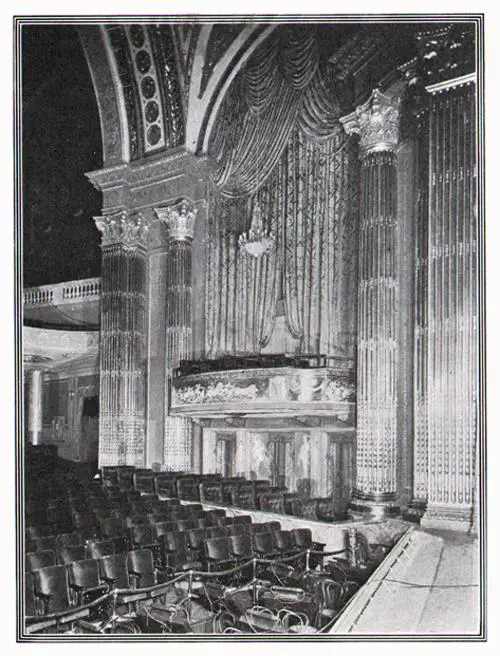

A PICTURE THEATER OF TODAY -- The interior of the largest theater in the world, the Capitol, New York City. A far reach from the nickelodeon a few years ago. It is devoted exclusively to photoplay. The Mentor, July 1921. | GGA Image ID #

In the West, I tried out my ideas for the making of a new sort of program and met with encouraging success. Later, I presented a motion picture in New York with appropriate music, harmonious lighting effects, and other features designed to please the senses.

Finally, a formula for program-making was worked out that covered the field of music, general news topics, drama, comedy, education, dancing, and architectural effects.

The American appreciates the beautiful but is impatient and will not sit through a long, tedious performance. He wants his entertainment well done but quickly done. The type of performance that suits him and attracts him is marked by rapidity and diversion.

If someone had predicted a dozen years ago that an orchestra, a chorus, soloists of international reputation, scenic artists, and a large mechanical staff would one day be part of the organization of a "movie" house, the prophet would have been called an irresponsible visionary. He was! And yet this very thing has come to pass.

When, in 1914, the first theater was erected in New York under my supervision to present the moving picture in a modern, aesthetic setting, there were dire predictions of failure. Rash and impractical! The idea and ideal of a dreamer! A great structure is splendidly decorated and equipped to show motion pictures.

The Capitol Theater, New York, has 5300 seats. Its great orchestra numbers eighty musicians. There is a chorus and a ballet. When we presented the master photoplay, "Passion," 175,000 came to see it during the two weeks run.

Producers spend millions to stir the jaded patron. A production into which dollars have been poured like water does not necessarily yield the big story, the continental success. When truth, humanness, and good taste replace little extravagance, the moving picture becomes an unparalleled medium for promoting culture, education, and the highest form of beauty.

"Films Beat Books," Says Edison - Using Motion Pictures In The Classroom

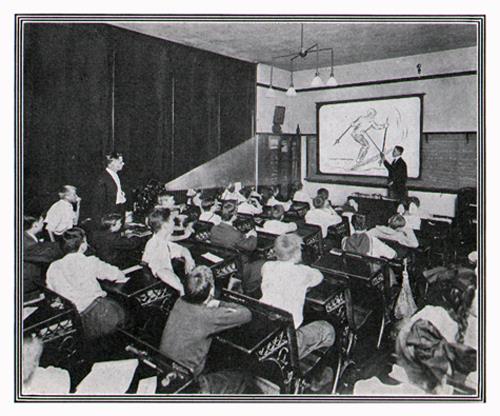

TEN years ago, Thomas Edison taught a group of children science using motion pictures. The results were so convincing that he expressed himself as "on fire to spread this means of education broadcast."

SEEING THE LESSON

Courtesy Patheseope Co. The Mentor, July 1921. | GGA Image ID #

"The royal road to learning lies along the film highway," says a college professor. More than one hundred schools in New York now use educational films. Every twentieth school in the United States has a projection machine.

Children who learn using motion pictures visualize the map's dots as hives buzzing with life and industry. History is reconstructed on the screen. Bygone days are lived over again; Joan of Arc, George Washington, Betsy Ross, and Napoleon become actual figures of romance and action.

Children learn through the eye without conscious effort. Dry-as-dust descriptions are replaced with amazing living pictures. They see the wheel of a Chinese potter shape a mass of clay into a beautiful vase; before their eyes, a mushroom breaks through the ground, and the beaver builds his dam.

A recent list compiled by the Society for Visual Education offers school films on various subjects. Early French explorations in North America are traced by animated lines moving upon Canada and the United States maps. Scenic pictures show the country the explorers traversed.

A subtle lesson in Americanism is taught in the film "A Citizen and His Government," which shows how the American Government furthers education and protects life, health, and property. One of the government's recent activities is the distribution of educational films to schools with motion picture equipment.

In an experiment recently conducted in an Illinois school, several classes were shown the life history of the Monarch butterfly on the screen. It was proven that a better understanding of this butterfly's life was gained from a fifteen-minute film exhibition than from two weeks of textbook study that had been given to another species.

In North Carolina, the Bureau of Community Service, a State organization designed to improve social and educational conditions, sends out "movie trucks," equipped with motion picture projectors and light plants, over circuits selected for their accessibility to the most significant number of people.

Films stimulate interest in museums' collections and cultivate people's taste in travel, crafts, arts, archaeology, and the history of races. During the past year, seventy thousand children saw the moving pictures given in the auditorium of the Toledo, Ohio, museum.

Manufacturers use films to demonstrate factory and distribution methods to workers, salespeople, and investors. A particular breeder of livestock had a thousand-foot reel made of his herd.

He bought a "suitcase projector," took it to the office of prospective buyers, attached the plug to a light socket, pulled down the shades, exhibited the pictures of his stock on the wall —and made six sales out of seven prospects.

The Nebraska Department of Conservation and Soil Survey uses miles of film every summer to report farming conditions.

A Japanese proverb says: "Once seeing is better than a hundred times telling about." We can teach almost anything with moving pictures.

Prepared for The Mentor by the Society for Visual Education.

The Open Letter on Screen Pictures - The History of Motion Pictures

What a story of progress in screen pictures the past quarter century tells! I wonder if any of the older Mentor readers remember the picture shows and panoramas of the days, or, rather, the nights of the seventies and early eighties! Does anyone recall Professor Cromwell and his picture lectures?

For years Professor Cromwell exercised the spell of the "magic lantern"—we came to know it later as the "stereopticon"—and he enhanced the charm of his entertainment with a piano at one side of the stage and a melodion at the other, on which he discoursed sweet musical strains, while he revealed the melting beauty of "dissolving views,"—a new thing then in picture shows.

In days before Professor Cromwell's innovations there were screen pictures that replaced each other abruptly, one after another, and panoramapictures that moved on rollers. How vivid and gaudy were the pictures of that time!

How bold and brave were the colors—colors that proclaimed in uncompromising tones, the courage and determination of the artisan that painted them on.

And the audiences of those simple days were delighted with the riot of color on the panorama screens—whether the colors were true or not. A purple cow was pleasing just because it was purple.

And, in those wonderful old panoramas, the greatest illusion of all was "night-lighting." Never will I forget the effect on my youthful mind of the panorama of "St. Peters and the Vatican, Rome," first by day, and then—by a simple trick of lighting from the back—the same scene illuminated at night.

The twinkling of lights in a thousand little windows held us young people spellbound. What thrilled us most was the thought that the spectacle of the superb Cathedral and the Papal palace should be all lit up just for us.

I have often wondered since whether St. Peters and the Vatican ever actually looked as gorgeous at night as our youthful eyes saw it on the screen of Professor Cromwell.

The day of Professor Cromwell, and all the other "Professors," passed and then came the treat of a perfected stereopticon. Progressive, intelligent, enterprising men like Stoddard, Burton Holmes, Elmendorf, and Newman traveled the world over and brought their treasures of splendid photography back to us.

As soon as the vita-scope entered the field they took that on—and also the "kinemacolor" process that gives us colors that closely reproduce nature's own.

These men have become our chief travel-picture benefactors. Through the winter evenings they have taken us nearly everywhere and shown us nearly everything.

The Elmendorf and Newman pictures are well known to Mentor readers for they are published in our pages; so, we enjoy the rich benefits of the experience of both of these distinguished camera artists.

* * *

And now we have the crowning achievement of modern photography, the Motion Picture Play—perhaps we might better say the picture plays have us, for they are about us everywhere. They are well named "movies," for, in the final analysis, that is their commanding appeal. They move.

Some might contend that the film pictures hold us because they show us great life-dramas. But, if any of those very same life-dramas were presented in a series of "still" pictures, the essential appeal would be lacking. It is because theymove. Throw some bits of crumpled paper on a table in a crowded room, and they will attract little attention.

Tighten those bits of paper with twisted elastic so that they jump around in a lively fashion, and everybody will crowd about the table and watch them with interest. What is the answer? Motion. Motion means life—and life is the supreme interest of human beings.

It was a great day for us mortals when Galileo said of the earth, "It moves." Everything on the earth has been more interesting since then.

THE MENTOR, Volume 9, Number 6, July 1, 1921