Why We Went to War - 1919

The Lusitania Leaving Her Pier at New York. This magnificent Cunard liner was torpedoed by a Gemían submarine, ten miles from Kinsale Head on the Irish coast. May 7, 1015. The ship sank in eighteen minutes. In this terrible wreck 1,150 people, among whom were 111 Americans, lost their lives. The wholesale slaughter of noncombatants without warning or opportunity for escape, in defiance of international law and the precedents of war between civilized nations, aroused the deepest indignation. Photograph © International News Service. Collier's Photographic History of the European War, 1915. GGA Image ID # 180f917a2e

Two years before our entrance into the war, Germany had been carrying on open warfare against us within our borders. Germany's policy of preparatory penetration had been in course for more than thirty years.

As we know now, every country, all round the globe, but especially the United States in North America and Brazil and Venezuela in South America, had been filled with Germans, ostensibly settlers, business men and followers of the higher professions, but for the greater part agents of Germany, in continuous contact with Potsdam and under Potsdam direction.

It was the business of these imported Germans to foster the German idea, exalt Germany’s leadership in military power and in science and the arts, impress their language, their literature, music and customs upon our people, and to do all those things which might work for the day when Germany, having faked a partnership with Almighty God, should reach out for world dominion.

The processes were pressed with that strange blend of industry, stupidity, mendacity and cunning which characterize the Prussian and all his acts. Under our noses a German solidarity was attempted here, and in part achieved. Organizations having Prussian ends in view were numerous, large, popular and unsuspected.

Threading them through and through was a spy system unbelievably thorough and amazingly adroit. Potsdam had us marked as a nation of easygoing money getters, to be bled white, crammed with her muddy kultur and taught the goose-step, at her imperial leisure, after France and England had fallen to her guns.

But her blend of qualities, no matter how strong in itself, was nullified by just one lack: the total inability of the Prussian mind to understand the mind of the world exterior to Germany. In the day of test, it failed.

Because of that inability, and knowing full well how readily the German mind could be terrorized, the outbreak of war in Europe brought an outbreak of blind German violence in the United States.

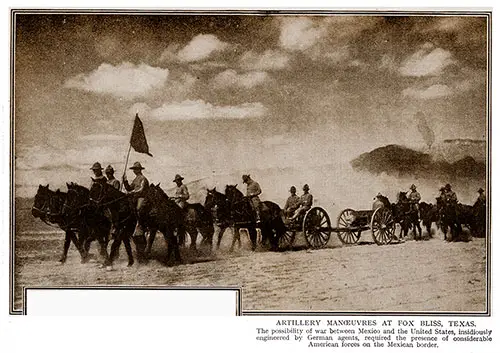

We were to be impressed by the German power to strike. Our soil was chosen as a garden of domestic sedition, and of foreign conspiracy against powers with which we were at peace. To keep us busy with troubles of our own, German propaganda and German money in Mexico raised on our southern border a threatening specter of war.

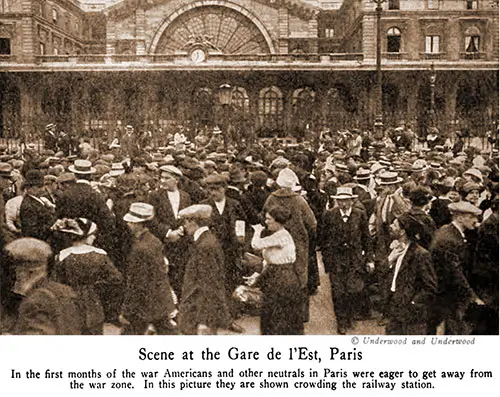

Scene at the Gare de l'Est, Paris. In the First Months of the War, Americans and Other Neutrals in Paris Were Eager to Get Away from the War Zone. In This Picture, They Are Shown Crowding the Railway Station. Photograph © Underwood & Underwood. Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume 1: The Great Explosion, 1920. GGA Image ID # 197f9a76da

We were to have been rushed into conflict with Mexico and kept employed there while being terrorized by wholesale arson and sabotage at home, so that by no chance could any friendly European power look to us for help.

The scheme came near to succeeding, for our people were aroused by Mexican aggression, and the flaunting insults of Mexican authority, prompted by German agents.

The policy of our Government saved us from falling into a trap that might have held us fast while Germany overran the whole of Europe and made ready to come a-plundering here at her own time and convenience.

If the truth had been known by the people then as clearly as it was known at Washington, nothing could have held us back. We would not have bothered with Mexico at all. We would have joined the free nations of Europe, and nobody may guess what would have happened.

Certainly, we could not have assembled the men and the resources we actually and swiftly did assemble later, when the real hour sounded. We would have cut a sorry figure and gone into the mess confusedly.

Washington knew. The President knew so well that through 1915 and 1916, he and others in high places never ceased crying a warning to “prepare.” The President himself toured the country and told the people everywhere that with a world on fire, we could not hope to escape unsinged.

He said openly as much as he dared. Under the surface, the Government did much more. The rapid movement of events once we were declared a combatant would have been impossible otherwise. That rapidity of effective action surprised the world only because it had all been planned before a word was said.

In the years of our neutrality, our course as a nation was surely shaping itself for war, without an outward sign or act. Ruthless destruction of property and of life became too open, too frequent, too outrageous, for the patience of even a long suffering, tolerant people such as we.

The first impulse of genuine resentment was given when the Lusitania went down with its neutral passengers, a defenseless ship on a peaceful errand, drowning more than a hundred Americans of both sexes and all ages without the slightest notice, or the faintest chance of escape.

Any nation, other than ours, would have gone to war in a moment over such a blow in the face. We did not. Farther, we endured a sudden and flagrant increase of German propaganda in high quarters and low, and of German insolence openly and defiantly parading itself.

The catalogue of provocations grew daily, and daily bred anger, but our temper held until in February of 1917, when Germany proclaimed unrestricted piracy by submarines, and under the thin pretext of starving out the British Isles, American and other ships were destroyed with all on board, wholesale.

Even then, our hand was withheld until Germany advised us that we might send just one ship a week to Europe, one ship and no more, provided that solitary ship were painted in a manner prescribed in the permission, and then held strictly to a course laid down by the German admiralty. Germany, a third rate naval power, had arbitrarily forbidden us the freedom of the seas.

Then our patience broke. For this, and all the other causes, Germany had given us, and for our own safety and the rescue of a world that, without us, would have perished, the United States went to war.

Artillery Maneuvers at Fox Bliss, Texas. The possibility of war between Mexico and the United States, insidiously engineered by German agents, required the presence of considerable American forces on the Mexican border. The Great War Magazine, Part 143, 12 May 1917. GGA Image ID # 180e356d67

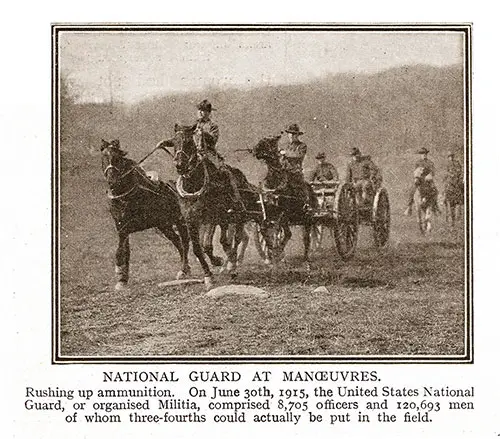

National Guard at Maneuvers. Rushing up ammunition. On June 30th, 1915, the United States National Guard, or organized Militia, comprised 8,705 officers and 120,693 men of whom three-fourths could actually be put in the field. The Great War Magazine, Part 143, 12 May 1917. GGA Image ID # 180e9a6bb3

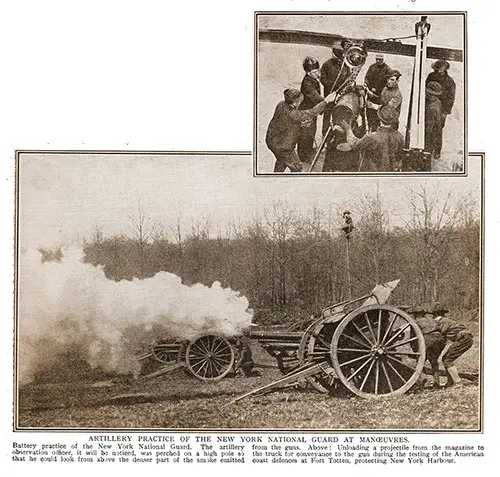

Artillery Practice of the New York National Guard at Maneuvers. Battery Practice of the New York National Guard. The Artillery Observation Officer, It Will Be Noticed, Was Perched on a High Pole So That He Could Look from above the Denser Part of the Smoke Emitted from the Guns. Above: Unloading a Projectile from the Magazine to the Truck for Conveyance to the Gun during the Testing of the American Coast Defenses at Fort Totten, Protecting New York Harbor. The Great War Magazine, Part 143, 12 May 1917. GGA Image ID # 180f0d6cd2

Thomas Herbert Russell, A.M., LL.D., "Chapter I: Why We Went to War," in The World’s Greatest War and Triumph of America's Army and Navy, Peace Treaty Edition, L. H. Walter, Publisher, 1919, pp. 17-24.