The United States Intervenes - 1917

President Wilson Addressing Congress About the Intervention of The United States of America. The Great War Magazine, Part 143, 12 May 1917. GGA Image ID # 17eb0dcf9b

On April 4, the Senate adopted a declaration of war by 82 votes to 6, and on the next day the House, by 373 votes to 50. And on April 6, 1917, the President issued a proclamation declaring that “a state of war exists between the United States and the Imperial German Government.”

Two days later the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Austria-Hungary, although a declaration of war against the Dual Monarchy was delayed until December 7.

Thus by April, 1917, the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany had brought the United States, the last of the world’s Great Powers, into the war on the side of the Allies.

Furthermore, German ruthlessness now stirred up a wave of pro-Ally sentiment among the remaining neutrals, and protests against submarine warfare and barred zones were speedily filed at Berlin by Spain, Holland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, China, and the republics of Latin America.

Within a week of America’s declaration of war, Brazil and Bolivia severed diplomatic relations with Germany, and Cuba and Panama formally joined the Allies.

The intervention of the United States was a godsend to the Entente, for at the time, as subsequently was generally admitted, the Entente was on its “last legs.” Russia was soon to quit the war altogether, and France and Italy were alike suffering from bad cases of “nerves.”

Now, however, the United States could put at the disposal of the Entente her rich metals, her copious foodstuffs, her numerous shipyards, her powerful fleet, her vast man power, and, most significant of all, her fresh enthusiasm and her unselfish idealism.

The character of the Great War in popular imagination was changed for the better, and the chances of victory for the public right were enormously increased.

Germany, already inferior to the Allies in natural resources and staying power, would soon be rendered hopelessly inferior. For this dénouement Germany had only her own ruthlessness to blame.

The Problem: Preparedness

Germany had staked everything on the success of her submarine warfare, and the intervention of the United States did not swerve her from her purpose. She realized that the United States was ill prepared for immediate active participation in the struggle in Europe.

No matter how energetic the American Government might be, it would certainly take the whole year 1917 for the United States to raise, train, equip, and transport to Europe an army large enough to have any appreciable effect upon the fortunes of the war.

Food, munitions, and shipping, in addition to men, would have to be supplied in enormous quantities not only for an American Expeditionary Force but for the Allies also, and as yet America was not ready to fulfill these obligations.

It would be the spring of 1918, at the earliest, before Germany need reckon seriously with the United States.

In the meantime Germany would vigorously prosecute her submarine warfare against Great Britain. Ruthlessly would she seek to destroy every merchant vessel endeavoring to enter or leave a British port, and in this way she would destroy Allied shipping, put a practical embargo on British industry and trade, deprive the Allied armies of munitions and supplies, and starve out the civilian population of the United Kingdom.

If all went well for the Germans, Great Britain would be brought to terms; and once Great Britain submitted, France and Italy and Russia would have to sue for peace.

And with Allied shipping destroyed and with the Allies submitting to the inevitable, there would be neither means nor purpose of transporting an American Expeditionary Force to Europe.

American intervention, Germany thought, could not be effective before the spring of 1918, and then it would be too late. Perhaps Germany was again over-optimistic, but at any rate the Allies themselves were worried.

They trembled when they tried to face the question. Could the United States complete preparedness before Germany had succeeded in her unrestricted submarine warfare?

No sooner had the United States declared war against Germany than special missions visited America from England and France — the British mission headed by Foreign Secretary Balfour, and the French by Ex-Premier Viviani and Marshal Joffre.

These missions explained the dire situation confronting the Allies and the urgent need for the United States not only to dispatch supplies of all sorts to their countries and to assist in averting the submarine danger but to rush large armies to France, if not immediately to engage in the actual fighting, at least to reassure the Allied troops that the United States was really in the war and thus to strengthen their morale. The response was sympathetic and enthusiastic.

It is perhaps regrettable that the American Government did not take advantage of the exigencies of the Allies and the visit of the foreign missions to make full participation of the United States in the war conditional upon the formal repudiation by the Entente of all existing “secret treaties.”

If this had been done, most probably the “secret treaties” would have been thrown overboard, the Great War in its subsequent phases would have been waged more distinctly in harmony with the spirit that impelled American intervention, and certain very troublesome problems which later confronted the Peace Congress would never have arisen or would have been solved more equitably.

As it was, however, the visiting missions carefully concealed from President Wilson the existence of numerous secret international engagements by which they were bound, notably the pledges made Japan in February, 1917, in respect of the German rights in the Chinese province of Shantung and the German Pacific islands north of the equator.

That the United States made no such conditions or reservations was a tribute to American unselfishness and likewise to the naïve faith of the American Government that all other Powers arrayed against Germany were equally unselfish.

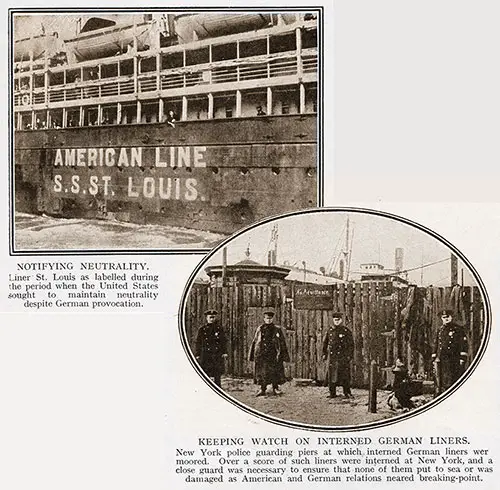

Top Photo. Notifying Neutrality: Liner St. Louis as Labelled During the Period When the United States Sought To Maintain Neutrality Despite German Provocation. Bottom Photo. Keeping Watch on Interned German Liners: New York Police Guarding Piers at Which Interned German Liners Were Moored. Over a Score of Such Liners Were Interned at New York, and a Close Guard Was Necessary To Ensure That None of Them Put To Sea or Was Damaged as American and German Relations Neared Breaking-Point. The Great War Magazine, Part 143, 12 May 1917. GGA Image ID # 17e1c26621

At any rate America was resolved to show the faith that was in her not alone by words but also by deeds.

It was none too soon. Even before the formal resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 1, 1917, Germany had made noteworthy progress in destroying Allied shipping and in hampering Allied commerce.

Since August, 1914, every month had witnessed the sinking of hundreds of thousands of tons of belligerent and neutral merchant vessels. In 1914 nearly 700,000 tons of British and Allied and neutral shipping had been destroyed ; in 1915 the amount increased to 1,700,000 tons; and in 1916 it soared to 2,800,000 tons.

Apparently, as time went on, the German submarines were becoming more numerous, more daring, and more experienced.

By February, 1917, submarine warfare had passed its trial stage and was to be put to the supreme test. And just as the German navy yards completed a host of new submarines and German factories equipped them with powerful torpedoes for their deadly work, the German Government laid aside all pretense of observing international law in their use and proclaimed the ruthless orders of February 1.

The German campaign of sea-ruthlessness started off with spirit and dash. From January to June, 1917, German submarines sank 2,275,000 tons of British shipping and 1,580,000 tons of allied and neutral shipping, — an aggregate loss to the Entente of nearly four million tons in six months.

If this huge total could be doubled in the second half of 1917, German hopes and Allied fears might be justified.

As a matter of fact, however, the spirit and dash which characterized the submarine campaign of Germany in the first half of 1917 were not sustained in the second half of the year, for the Allies were finding means of lessening the menace.

Merchant vessels began to sail under convoy, guarded above by dirigible balloons and hydroplanes, and on the surface by a fleet of patrol boats.

Close watch was kept of the movements of submarines, either by means of lookouts on patrol boats or by means of wireless operators who detected messages passing between the submarines and the German naval bases.

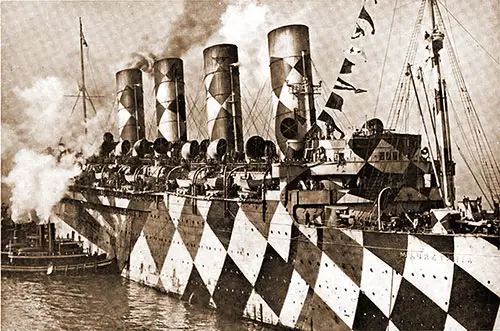

In the Spring of 1918, the "Mauretania" Brought 33,000 American Soldiers to Europe, Shown in Her Dazzle Paint. A Merchant Fleet at War, 1920. GGA Image ID # 18af57db40

The camouflaging of Allied ships, moreover, proved a useful deception; “the war brought no stranger spectacle than that of a convoy of steamships plowing along through the middle of the ocean streaked and be spotted indiscriminately with every color of the rainbow in a way more bizarre than the wildest dreams of a sailor’s first night ashore.”

Gradually, Allied naval commanders were enabled to trap and destroy, or capture, German submarines; and the German authorities found it increasingly difficult to repair and replenish their submarines and to make their sailors undertake joyfully the new hazards of life in a periscope.

Though the losses to Allied shipping continued heavy throughout 1917 and far into 1918, the turn of the tide was reached in the midsummer of 1917.

In the second half of 1917 the destruction of Allied and neutral shipping amounted in the aggregate to two and three-fourths million tons, as against nearly four millions in the first half of the year.

It was obvious that Germany had miscalculated the success of unrestricted submarine warfare and that Great Britain would not be brought to terms by the spring of 1918.

It became obvious, too, that Germany had miscalculated the time required for the United States to intervene actively in the war. For the United States, after declaring war on April 6, 1917, lost no time in collecting vast sums of money, in gathering and training a large army, and in mobilizing industries and resources.

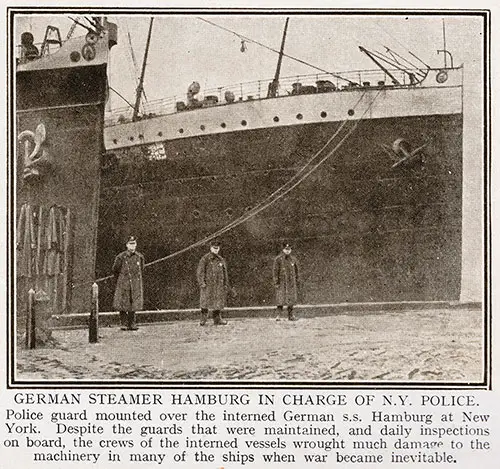

German Steamer Hamburg in Charge of N.Y. Police. Police Guard Mounted over the Interned German S.S. Hamburg at New York. Despite the Guards That Were Maintained, and Daily Inspections on Board, the Crews of the Interned Vessels Wrought Much Damage to the Machinery in Many of the Ships When War Became Inevitable. The Great War Magazine, Part 143, 12 May 1917. GGA Image ID # 17e1d0e589

Immediately German ships in American harbors were seized, and the navy and the small standing army were mobilized. A Council of National Defense was formed, comprising the secretaries of war, navy, interior, agriculture, commerce, and labor, with an advisory commission of seven men drawn from civil life, and with a host of affiliated local boards and committees throughout the country to assist in coordinating America’s war efforts.

To arouse an intelligent popular enthusiasm for the war, a Committee on Public Information was created under the chairmanship of George Creel.

There was some natural and inevitable “muddling” in transforming America suddenly from a peace footing to a war basis, but, considering the manifold difficulties and handicaps, the task as a whole was achieved with surprising efficiency and dispatch.

A Selective Service Act, passed in May, authorized the President to increase the regular army, by voluntary enlistment, to 287,000 men, the maximum strength provided by existing law; to draft into service all members of the National Guard ; and to raise by selective draft an additional force of 500,000 men, and another 500,000 at his discretion.

The age limits for drafted men were twenty-one and thirty years, and all male persons between these ages were required to register “in accordance with regulations to be prescribed by the President.”

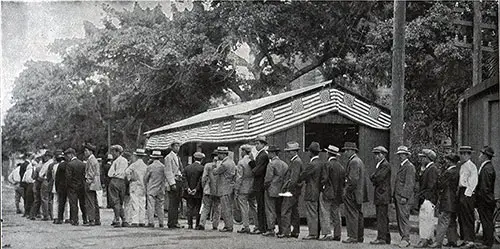

The Draft Registration Lineup In Honolulu Hawaii, 1917. GGA Image ID # 1821d8185e

On June 5, “registration day,” some nine and one-half million young Americans enrolled, and the drawing of the 625,000 men to form the first selective army took place at Washington on July 15. In July the National Guard was mobilized, and in September the mobilization of the new national army began.

Meanwhile Congress was enacting a series of important war measures: two liberty loan acts (April and September); an espionage act, in June; an aviation act, in July; food control and shipping acts, in August; and in September, a revenue act imposing war taxes on income and excess profits, a trading-with- the-enemy act, and a soldiers’ and sailors’ insurance act.

During the congressional session which closed in October, 1917, appropriations were made totaling nearly nineteen billion dollars, of which seven billions were to cover loans to the Allies.

In July Mr. Herbert Hoover became “food dictator,” and in August Mr. Garfield was appointed “fuel administrator.” In December the Government took over the management and operation of the railways.

Every possible step was taken to expedite the production of munitions and other war supplies, including foodstuffs, and to transport all these commodities to American seaports on the Atlantic coast and thence to Europe for the relief alike of the armed forces and of the civilian population, of the nations now associated with the United States in the Great War.

To place American grain, meat, munitions, and money so promptly and so effectively at the disposal of the Allies was of itself no mean contribution of the United States to the eventual defeat of Germany.

But the United States Government was resolved to go much farther and to put American troops in front-line trenches alongside those Allied troops who for two years and a half had borne the heat and burden of the greatest war in history.

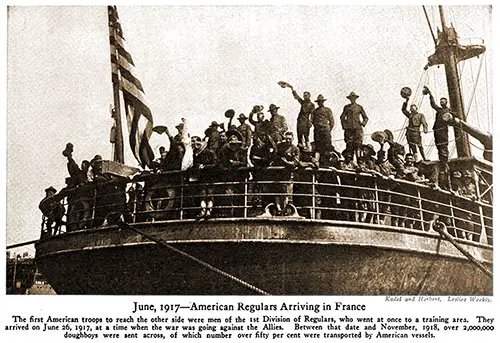

On June 13, General John J. Pershing, who had been designated to command the projected American Expeditionary Force abroad, arrived in Paris, and the first contingent of American troops reached France on June 25.

June 1917—American Regulars Arriving in France. the First American Troops to Reach the Other Side Were Men of the 1st Division of Regulars, Who Went at Once to a Training Area. They arrived on June 26, 1917, When the War Was Going Against the Allies. Between That Date and November 1918, Over 2,000,000 Doughboys Were Sent Across, of Which Number Over Fifty Percent Were Transported by American Vessels. Photograph by Kadel and Herbert. Courtesy of Leslie's Weekly. Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume 3, 1920. GGA Image ID # 18c558edae

The first American shots from European trenches were fired on October 27, and the first trench fighting of Americans occurred a week later.

By December, 1917, about 250,000 American troops had been safely landed in France; and towards the end of January, 1918, the War Department at Washington let it be known that United States soldiers were occupying frontline trenches “in a certain sector.”

Against American preparations the German submarine warfare made little headway. It is true that during the first year of unrestricted submarine warfare, ending January 31, 1918, some sixty-nine American vessels, representing a gross tonnage of 170,000, were sunk by submarines, mines, or raiders.

On the other hand, it should be remembered that enemy merchant ships were seized by the United States to the number of 107, with an aggregate tonnage of nearly 700,000, and that many of these former German and Austrian liners were promptly repaired and used to carry American troops and supplies to France.

Besides, the United States Government inaugurated a shipbuilding program of huge dimensions, so that by the first anniversary of America’s participation in the war the United States had put in commission 1275 vessels of every sort of service — mine-sweeping, mine-laying, transport, patrol, and submarine-chasing.

By the same date the personnel of the American navy had grown from its original number of 4800 officers and 102,000 men to 20,600 officers and 330,000 men, and the navy itself with great speed and small loss was conducting the most amazing ferrying business on record.

Before the spring of 1918 had rolled around, the problem of American preparedness was solved, and it was solved in manner wholly disconcerting to the Teutons.

At the beginning of 1917 Germany had, with mad imprecations, unloosed the ruthless submarines in order to bring Great Britain to terms.

At the close of 1917, despite the submarines and the fierce invectives of Germany, Great Britain was still resolutely hostile.

Nay, more, at the close of 1917, because of those same submarines and invectives, the United States was an active associate of the Entente, pouring out to Britain and France and Italy vast streams of food and minerals and treasures and, most startling of all, her own manpower.

Verily it was a new stage of the Great War which the intervention of the United States marked, and one ominous to Germany’s vaulting ambitions and likewise to any perpetuation of international anarchy.

Colton J. H. Hayes, Excerpts from "Chapter X: The United States Intervenes", in A Brief History of the Great War, New York: The MacMillan Company, 1922, pp. 218-224