Prelude to War: The Zimmermann Telegram - 1917

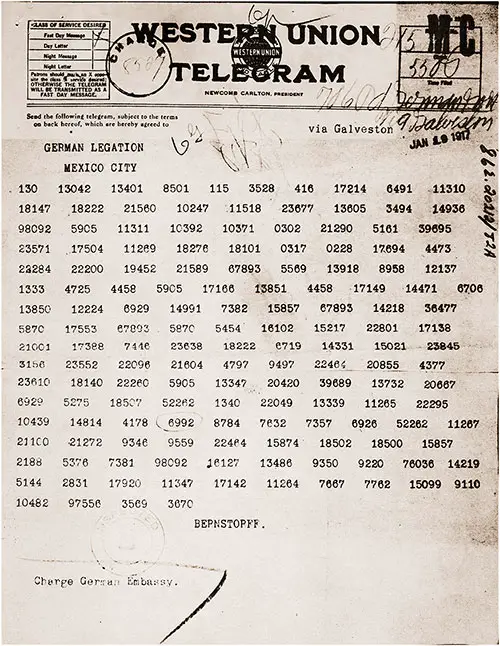

German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann Sent This Encoded Message to the President of Mexico on January 16, 1917, Offering United States Territory to Mexico in Return for Joining the German Cause in World War I. in Return for Mexican Support, Germany Would Help Mexico Regain New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona from the United States. National Archives & Records Administration NARA ID # 302025. GGA Image ID # 197e23375a

British intelligence intercepted the telegram and deciphered it. To protect their intelligence from detection and capitalize on growing anti-German sentiment in the United States, the British waited until February 24 to present the telegram and its translation to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. The American press published news of the telegram on March 1. On April 6, 1917, the United States Congress formally declared war on Germany and its allies.

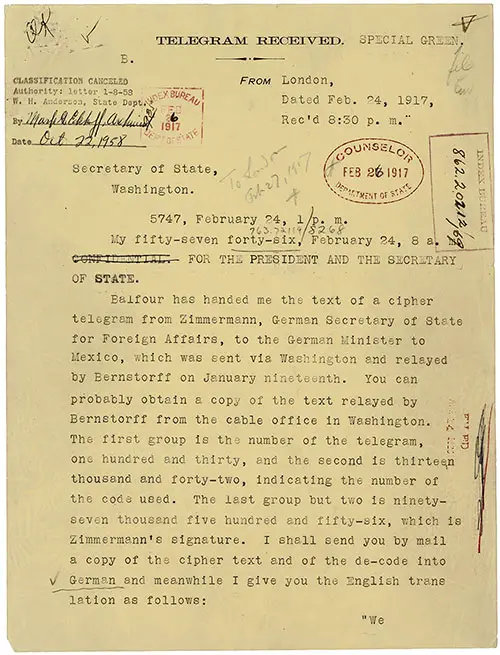

U.S. Ambassador Walter Page sent this telegram to President Woodrow Wilson, conveying a Zimmermann Telegram translation. In January 1917, the United States was neutral in the European war that would eventually be called World War I. The Zimmermann Telegram would be the catalyst to change everything.

German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann sent an encoded message to the President of Mexico. The Germans revealed plans to begin unrestricted submarine warfare, and Germany proposed an alliance with Mexico on January 16, 1917. British intelligence intercepted the telegram and deciphered it. After decoding the message, the British Government passed its contents on to the American Government. The British ambassador expressed that the British Government would like how the telegram was intercepted to be kept secret. Still, it has no restriction on making the telegram public.

The decoded message that Germany sent to Mexico reads:

FROM 2nd from London # 5747.

We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support, and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President's attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace.

Signed, ZIMMERMANN

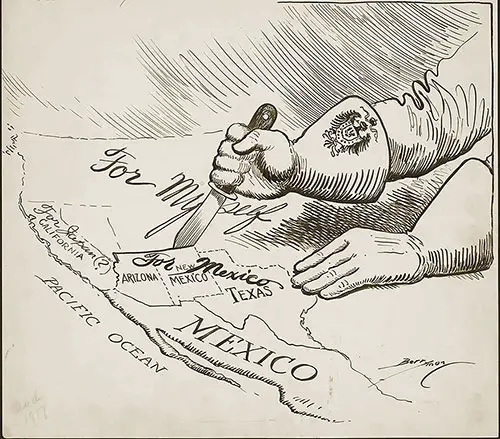

Clifford Berryman. Hand carving up a map of the Southwestern United States, 1917. Ink and graphite drawing. Probably published in the Washington Evening Star, March 1917. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. GGA Image ID # 197e383e6a

Telegram from US Ambassador Walter Page to President Woodrow Wilson

First Page of the Telegram from U.S. Ambassador Walter Page to President Woodrow Wilson Conveying a Translation of the Intercepted Zimmermann Telegram from Germany to Mexico, in Which Germany Proposed an Alliance and Disclosed Its Plans to Begin Unrestricted Submarine Warfare, February 24, 1917. Lost and Stolen Documents Section, National Archives and Records Administration. GGA Image ID # 197e4f3ca3

The Story Behind the Zimmermann Telegram

In 1917, as World War I dragged on in Europe, a neutralist President Wilson and a mostly apathetic American public wanted little to do with the European conflict. Wilson had just won reelection under the slogan, "He kept us out of war."

However, one supremely significant event early in that year would change the entire country's attitude toward the war in general and Germany in particular.

That event was the publication of what came to be known as the Zimmermann Telegram, so named because its author was Arthur Zimmermann, imperial Germany's foreign minister.

In it, Zimmermann secretly proposed to Mexico, then hostile to the United States, an alliance with Germany. The Germans would provide Mexico with ample supplies that the Mexicans would be free to reconquer Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

He further suggested that the Mexican president invite Japan, nominally an Allied nation but of great strategic concern to the United States, to join the German-Mexican pact.

Naturally, when the German attempt to bring the war to the territory of a neutral United States became known (and Zimmermann inexplicably acknowledged authorship), the American view of Germany was so altered that within five weeks that one message had accomplished what even the earlier German declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare had not: the United States declared war.

Inside Germany, there was a thorough investigation of how the top-secret, coded telegram came into the United States government's possession. A translation of the report of that investigation follows. The Germans concluded that their codes had not been broken and attributed the compromise to treason. They could not have been more wrong because the truth was that the revelation of the Zimmermann telegram was the greatest cryptologic triumph of the First World War.

On the first day of the war, the British cut Germany's transatlantic telegraph cable, compelling the Germans to send all telegrams to the Western Hemisphere via neutral countries or cables that passed through enemy territory.

Simultaneously, the British government accelerated developing a cryptographic office whose purpose would be to read enemy traffic. This organization came to be known as Room 40 because of its location in the Old Admiralty Buildings.

Staffed with competent people and aided by the Russians' lucky physical recovery of the German naval codebooks in the Baltic Sea, it increased in importance and capability. During the first two years of the war, Room 40 concentrated primarily on tactical maritime traffic.

However, once its successes had helped the British navy to bottle up the German fleet, it turned to the breaking of German Traffic of a more strategic value. On 17 January 1917, it was presented with its most significant opportunity of the war.

On that morning, Room 40 intercepted a coded German diplomatic message from Foreign Secretan Zimmermann to Count von Bernstorff, the German ambassador in Washington.

It was able to do so in two ways because neutral but pro-German Sweden was transmitting messages for Germany, the British had tapped into the Swedish cable to South America, where it passed by England. Zimmermann had sent one copy of his telegram in this route, with instructions that the German ambassador in Buenos Aires forward it to Washington. Room 40 got it.

To ensure receipt, however. Zimmermann had sent it in a second and far more audacious way: he had the American ambassador in Berlin telegraph it to the State Department in Washington, which in turn hand-delivered it to the German embassy.

This arrangement had been made possible by President Wilson, who was trying to mediate an end to the war and had offered to transmit German diplomatic messages to Washington when the Germans protested that they could not communicate confidentially with their ambassador there.

This copy traveled via Copenhagen, then London, on its way to the United States, with instructions to the German ambassador to forward it to Mexico. Room 40 got it when it passed through London.

Both versions of Zimmermann's telegram were enciphered using code OO75, which the British had already partially broken. With two copies at their disposal. They were able to piece together enough of the message to recognize the substance of it.

Admiral William Hall, Director of Naval Intelligence and head of Room 40, ordered that the telegram's existence be kept secret from all other agencies while Room 40 cryptographers filled in the gaps in the message.

The British used intercepts of other German traffic sent in code 0075 to recover additional code groups. By February 5, the task was sufficiently complete for Hall to share the British foreign office's decoding.

It was immediately apparent that the telegram was of inestimable value in finally drawing the United States into the war on the Allied side, a long-time British objective.

Still, there were problems to be solved before Room 40 could share the message with the United States government. First, Room 40 was one of the British government's darkest secrets.

Its existence as the source of the compromise had to be concealed from the Germans. Likewise, the British needed to conceal from the Americans that they had been Reading American traffic, a touchy issue in that the United States was a neutral country.

Third, the telegram still contained a few gaps that might lead the Americans to question its authenticity or actual meaning. Hall hit upon an ingenious idea that addressed all three issues.

Using a contact in the Mexico City telegraph office, he obtained a copy of the enciphered message that had been forwarded from the German embassy in Washington.

This version had been sent using code 13040 since the embassy in Mexico did not hold code 0075. As an older and less sophisticated code, the British had recovered most of it and were able to read virtually the entire text, allowing them to fill in the remaining gaps.

As a forwarded message, the telegram had been given a new date and header information by the Washington embassy. This version would allow the British to convince the Americans that the message was obtained in Mexico and lead the Germans to suspect the same. The Americans would therefore conceal room 40's role.

Because Germany had just declared unrestricted submarine warfare and the United States had broken off diplomatic relations; as a result, Great Britain held the telegram for more than two weeks, hoping that it wouldn't be needed to prod the United States into war.

However, when nothing happened, on February 22, the British delivered the Zimmermann note to American ambassador Walter Page, who greeted it with outrage.

The British told him that they had no objection to its publication but requested that Great Britain not be revealed as the source.

They used the Mexican cover story, which Page accepted, to explain their telegram acquisition, thus hiding their reading of American message traffic.

Page telegraphed President Wilson with the news on February 24, setting in motion a chain of events in the United States that wholly altered the nation's perception of German war intentions.

As the British had requested, the United States government did not reveal the telegram's source when it allowed the Associated Press to publish it three days later.

A cover story was devised in which the United States claimed that it had obtained the telegram itself but could say no more out of concern for the lives of the persons involved.

To support this story, the government retrieved from the Washington office of Western Union the coded original from Ambassador von Bernstorff to the German embassy in Mexico.

The American government sent this to London, where, using keys provided by Room 40, an official of the United States embassy deciphered the message.

This allowed President Wilson to truthfully state that he had obtained the Zimmermann telegram and its decoded version from his people, thus blunting many pacifists' argument that the message was a fake supplied by Great Britain or France to inflame American opinion.

The American people widely accepted the story in Congress and the country, and the war was declared little more than a month later. However, as is evident from the following translation of the official German report that erroneously pointed the finger at an unknown traitor, Room 40 and cryptology's critical roles in bringing about this momentous event remained secret.

It is very probable that without the German foreign minister's message to the Mexicans, some other circumstance such as mounting American casualties and commercial losses as a result of unrestricted submarine warfare would have eventually drawn the United States into the war.

However, there can be no doubt that the Zimmermann Telegram's deciphering significantly hastened this certainty, clearly the most significant cryptologic coup of the First World War.

Bibliography

"The Zimmermann Telegram," in Cryptologic Quarterly, NSA, nd (Unclassified) pp. 43-46

"The Zimmermann Telegram: Making Connections, DocsTeach: The Online Tool for Teaching with Documents, National Archives & Records Administration. https://www.docsteach.org/activities/teacher/the-zimmermann-telegram Retrieved 10 April 2021.